June 6th, 1944 0130 hours. General Major Wilhelm Fi, commander of the German 91st Division, receives an impossible phone call from his headquarters in Picavville. Thousands of American paratroopers are landing across the Cottontown Peninsula behind the Atlantic Wall. Fi studies his map. His 88 anti-aircraft batteries haven’t fired a single shot.

His 12 coastal radar stations detected nothing. Yet the reports keep flooding in. White parachutes everywhere. Transport planes disappearing into darkness. American soldiers already on the ground. But Fi knows one thing with absolute certainty. The Atlantic wall is impenetrable. 2,400 km of fortifications, 2 million mines, 500,000 beach obstacles, 12,000 anti-aircraft guns.

No airborne force can penetrate that barrier without being annihilated. What doesn’t know is that 13,000 American paratroopers are already behind his lines. 20 minutes earlier, 116 hours, the first C-47 Dakotas cross the Norman coast at 500 ft altitude, flying at 115 mph. Formation, nine columns of aircraft, each 2 m long, spaced 1 m apart.

Total length of the aerial convoy, 300 m. Flight time over German occupied territory 12 minutes from coast to drop zone. German response time to scramble night fighters 18 minutes. The mathematics are brutal. By the time German radar stations identify the convoy, process the information and alert Luftwafa night fighter bases.

The paratroopers are already on the ground. 30 minutes before the main force, Pathfinder teams, reconnaissance airborne squads equipped with Rebecca radar and Eureka radio beacons had already landed. Their mission mark drop zones with infrared lights visible only through special goggles. Guide the 822 aircraft following them to precise landing coordinates.

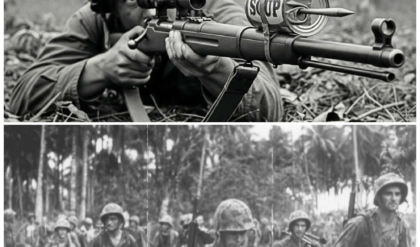

The Germans have no countermeasures for this technology. 0121 hours. The 82nd Airborne Division jumps. 6,420 men in three waves carried by 369 C47s. The planes fly at 500 ft barely above the treetops at 110 mph. Anti-aircraft fire tears through the formations. Aircraft burn. Men jump into tracer fire. Some planes take direct hits.

Paratroopers leap from burning fuselages. Others land in flooded fields prepared by Raml. Waste deep water that drowns men weighted down with 80 lb of equipment. But the majority land on target. The 5005th Parachute Infantry Regiment, the 82nd most experienced unit, achieves 50% accuracy within one mile of designated drop zones, 75% within 2 mi.

It’s the most accurate drop of D-Day or 0130 hours. In his concrete bunker at Picovil, Phi receives the first coherent report. The radio crackles with contradictory information. Paratroopers near S Marie Glee. Others near the Murdered River. Gliders crash landing in fields. Pathfinder teams marking drop zones with colored lights. Fi studies the map.

If the reports are accurate, the Americans have dropped an entire airborne army behind his lines. Not hundreds of men, not a raid. 13,000 paratroopers delivered by over 1,000 aircraft in the heart of the night. But something doesn’t add up. Reports are coming from 40 mi of front. Two dispersed, too simultaneous. What valley doesn’t know.

While 13,100 real paratroopers descend on the Cotent Peninsula, RAF bombers are dropping 500 dummy paratroopers. Life-sized manquins equipped with firecrackers that simulate gunfire across 40 mi of Norman countryside. German units rush to intercept phantom landings. Radio networks saturate with contradictory reports. Command and control collapses.

200 hours. Valley receives confirmation. Ser is under attack. The 505th parachute infantry regiment has landed with precision. American demolition teams with C2 explosive are cutting German supply routes. The bridges over the murderet are under assault. Fall’s 91st division is being isolated. 0 to30 hours.

More reports flood in, but they’re fragmentaryary, confusing. Fall needs to see the situation personally. He makes a decision. He’ll return from the war games in Ren, assess the situation himself, and organize a counterattack. The Americans are dispersed, disorganized, vulnerable. If he moves fast, he can annihilate them before they consolidate. 0300 hours.

Fi leaves headquarters in a Kubalvagen, driving north toward the sound of gunfire. With him, his driver, and a liazison officer. The road is dark. Norman hedros thick earthn walls topped with vegetation line both sides visibility 15 m 0330 hours on the road between picovil and s me gle’s kubalvagen rounds a corner a patrol from the 82nd airborne division four men armed with M1 Garand rifles is positioned behind a hedger distance 15 m the garans fire eight rounds of30-6 caliber in 4 seconds rate of Fire 40 to 50 rounds per minute. Effective range

500 m. The German car 98K fires five rounds in 10 seconds. Rate of fire 15 rounds per minute. The technological gap is 3:1. Phi dies instantly. He is the first German general killed on D-Day. 330 hours. 3 hours after the first paratrooper drop. The 91st division loses its commander. The counterattack will never be organized.

The Atlantic Wall with its 2 million mines and 12,000 guns has been rendered completely irrelevant. Not by a frontal assault, but by 13,000 men who dropped behind it in 90 minutes. But Fi’s death was a symptom of a larger problem. The Atlantic Wall, the fortress that was supposed to stop the invasion, had been bypassed.

The 13,000 paratroopers weren’t attacking the bunkers. They were behind them cutting roads, destroying bridges, ambushing convoys, creating chaos in the rear areas. The Germans had built a wall. The Americans had simply flown over it. At St. Margle, Lieutenant Colonel Edward Krauss and 180 men from the 5005th Parachute Infantry Regiment captured the town at 0430 hours.

They raised the American flag in the town square, the first French town liberated on D-Day. German reinforcements trying to reach Utah Beach now had to detour around Sant Glee, adding hours to their response time. At Lafier, a stone bridge over the Murderet River became a killing ground.

The 82nd Airborne held the western approach. German forces held the eastern side. For 3 days, the bridge changed hands in brutal close quarters fighting, but the Germans couldn’t mass forces for a counterattack. Every time they tried to move troops, they ran into scattered groups of paratroopers. At the causeways behind Utah Beach, the 101st Airborne secured three of the four exits by 0800 hours.

When the fourth infantry division landed at 0630, they didn’t face the expected slaughter. The causeways were open. The inland defenses were disrupted. The amphibious assault, the most dangerous phase of the invasion, succeeded because the airborne troops had already won the battle in land. By noon on June 6th, the situation was clear.

The Atlantic Wall had held at Omaha Beach, where no airborne troops had landed. But at Utah Beach, where 13,000 paratroopers had dropped behind the defenses, the invasion succeeded with minimal casualties. The wall was intact, but it was facing the wrong direction. By June 7th, the strategic situation in Normandy was clear to the German high command.

The Allies had established five beach heads. Over 150,000 troops had landed in the first 24 hours, and the airborne troops, those 13,000 paratroopers who had dropped behind the Atlantic wall, were still fighting 20 mi inland, blocking every German attempt to counterattack. General Feld Marshall Irvvin Raml arrived at his headquarters at Laros Gong at 2200 hours on June 6th.

He had been in Germany celebrating his wife’s birthday when the invasion began. The drive back took 14 hours, roads clogged with refugees, bridges destroyed by Allied bombers, resistance fighters cutting telephone lines. When Raml saw the reports, he understood immediately the Atlantic Wall had failed.

Not because the bunkers were weak. They had held at Omaha Beach, inflicting terrible casualties. But because the Americans had bypassed the strongest defenses entirely, at Utah Beach, where the airborne assault had succeeded, the Fourth Infantry Division had landed with fewer than 200 casualties. The causeways were open. The inland roads were cut.

The German reserves couldn’t reach the beach. RML had warned about this. For months, he had argued that the invasion had to be stopped at the waterline, that once the allies established a foothold, their industrial superiority would be overwhelming. He had wanted the Panza divisions positioned close to the coast, ready to counterattack within hours.

But Hitler had refused. The Panzas were held in reserve 100 m in land under direct control of OKW, the German high command. Moving them required Hitler’s personal authorization. On June 6th at 4:00 hours, the same moment General Major Fall was killed by American paratroopers, General Oburst Alfred Yodel, Hitler’s chief of operations, was informed of the invasion.

He chose not to wake Hitler. The Furer had been up late the night before. Yodel decided the reports could wait until morning. By the time Hitler authorized the release of the Panzer reserves, it was 1600 hours on June 6th. 12 critical hours had been lost and when the panzers finally moved, they were attacked relentlessly by Allied fighter bombers.

The 12th SS Panzer Division moving from Lisure toward Kong took 18 hours to cover 50 mi. Normally the journey took 3 hours, but every road, every bridge, every crossroads was under air attack. The Panzer Division, one of Germany’s elite armored units, lost five tanks and 84 halftracks before it even reached the front line.

And in the Cotton Peninsula, where the 82nd and 101st Airborne were still fighting, the situation was even worse. The paratroopers had cut the main roads. German units trying to reach Utah Beach had to detour through narrow country lanes where they ran into ambushes, roadblocks, and minefields. A journey that should have taken 2 hours took eight.

By the time German reinforcements arrived, the beach head was consolidated. RML studied the map at Lar Roong. The airborne assault had achieved something remarkable. 13,000 men scattered across 20 m of enemy territory had paralyzed an entire German army. They hadn’t destroyed the Atlantic wall. They had made it irrelevant.

The wall was still there. 2,000 bunkers, 200,000 obstacles, 2 million mines. But it was facing the wrong direction, and the battle was being fought behind it. The airborne assault on D-Day was not without cost. Of the 13,000 paratroopers who jumped into Normandy on June 6th, 2,500 were killed, wounded, or missing within the first 24 hours.

The 82nd Airborne Division lost 1,259 men. The 101st Airborne lost 1,240. Many drowned in the flooded fields of the Murderet River Valley. Others were killed before they hit the ground, shot by German anti-aircraft fire as they descended. Some landed in the middle of German positions and were captured immediately. Equipment was lost.

Radios, mortars, medical supplies scattered across miles of Norman countryside. The glider assault, Operation Detroit, and Operation Kyok was even more costly. At 0400 hours on June 6th, 52 Waco gliders carrying reinforcements for the 101st airborne crash landed near the causeways behind Utah Beach.

The gliders were towed by C-47s released at 400 ft and glided silently toward landing zones marked by pathfinders. But in darkness with anti-aircraft fire and ground obstacles, the landings were brutal. Gliders smashed into hedgerros, trees, and German defensive positions. Men were crushed. Equipment was destroyed. At 2100 hours on June 6th, a second wave of 200 gliders brought in artillery, jeeps, and anti-tank guns for the 82nd Airborne.

This time, the landing zones were under German fire. Gliders were hit before they touched down. Others landed in the wrong fields and were immediately attacked, but despite the casualties, the mission succeeded. By June 7th, both airborne divisions had consolidated their positions. The 101st Airborne held all four causeways behind Utah Beach.

The 82nd Airborne controlled St. Mary Glee and the bridges over the Murderet River. German counterattacks were repulsed. Reinforcements were blocked. The beach head expanded. On June 8th, elements of the fourth infantry division linked up with the 101st Airborne near Saint Marie Deong. The amphibious and airborne forces were now a single continuous front.

The Atlantic Wall, breached on June 6th, was now 20 mi behind Allied lines. By June 12th, the five Allied beach heads had merged into one continuous lodgement, 50 mi wide and 10 mi deep. Over 326,000 troops, 54,000 vehicles, and 104,000 tons of supplies had been landed. The port of Sherborg, the strategic objective in the Cottontown Peninsula, was under siege.

Sherborg fell on June 26th, 20 days after D-Day. The 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, which had dropped behind enemy lines on June 6th, fought continuously for 33 days before being withdrawn to England. They had suffered 40% casualties, but they had accomplished their mission. The Atlantic Wall, 2 years in construction, billions of Reichs marks in cost, the centerpiece of German defensive strategy, had been bypassed in 90 minutes by 13,000 men dropping from the sky.

The success of the D-Day airborne assault wasn’t just about courage or tactics. It was about technology and the industrial capacity to deploy that technology at scale. The C-47 Dakota was the key. Without it, Operation Neptune would have been impossible. The aircraft was reliable enough to fly in formation at night through anti-aircraft fire and deliver its cargo with precision.

It was simple enough that pilots with 200 hours of training could fly it safely and it was mass-produced. By June 1944, Douglas Aircraft Company was building 14 C-47s per day. But the C-47 was just one piece of a larger system. The paratroopers wore T5 parachutes designed by the Pioneer Parachute Company, tested over two years, manufactured by the thousands in Connecticut.

Each parachute was packed by hand, inspected three times, and guaranteed to open within 2 seconds of deployment. The Pathfinders used Eureka radar beacons developed by the telecommunications research establishment in Britain, manufactured by Western Electric in the United States. The beacons transmitted a signal that aircraft could detect from 20 m away, allowing precise navigation in darkness and bad weather.

The Germans had no equivalent technology. The paratroopers carried M1 Garand rifles, semi-automatic 8 round capacity, effective range 500 yd. The German infantry still used bolt-action CAR 98K rifles. In close combat, the American paratroopers had a decisive firepower advantage. And then there was the logistics.

Each paratrooper carried 90 lb of equipment. Rifle, ammunition, grenades, rations, water, medical supplies, entrenching tool, gas mask. The equipment was distributed in leg bags and muset bags designed to drop with the paratrooper and be quickly accessible after landing. The 1001st Airborne Division alone required 1,200 tons of equipment for the D-Day jump.

parachutes, weapons, ammunition, radios, medical supplies, food. All of it had to be transported from the United States to England, stored in secure facilities, distributed to units, inspected, and loaded onto aircraft in the correct sequence. The Germans couldn’t match this, not because they lacked courage or skill.

German paratroopers had proven their effectiveness in Cree in 1941, but because they lacked the industrial base. Germany in 1944 was fighting on three fronts, East, West, and Italy. Resources were stretched, fuel was scarce, aircraft production was prioritized for fighters and bombers, not transports. The United States, by contrast, was producing more of everything, more aircraft, more parachutes, more radios, more ammunition, more fuel.

The American economy in 1944 was operating at full capacity. factories running three shifts, women working assembly lines, liberty ships delivering supplies across the Atlantic faster than Ubot could sink them. The D-Day airborne assault was a demonstration of that industrial power. 13,000 men delivered by 1,087 aircraft supported by 2,000 bombers and fighters coordinated with naval gunfire from 200 warships.

It was a symphony of logistics, technology, and mass production that no other nation in 1944 could replicate. And it changed warfare forever. The Atlantic Wall still exists. You can visit the bunkers today. Massive concrete structures, some with walls 12 ft thick, gun imp placements facing the sea, observation posts with commanding views of the beaches.

They are monuments to a defensive strategy that failed. Not because the defenses were weak. Omaha Beach proved they could be devastatingly effective. 2,400 American casualties in the first hours, the bloodiest fighting of D-Day. But because static defenses, no matter how strong, can be bypassed. General Major Wilhelm Thali understood this too late.

On the morning of June 6th, driving through the darkness toward his headquarters, he saw the evidence. Parachutes in the fields, gliders crashed in hedgerros, American soldiers moving through the countryside. The war had moved behind him. The Atlantic Wall, which he had helped defend, was now irrelevant. He died at 4:00 hours, killed by men who had dropped from the sky 3 hours earlier.

He was the first German general to die on D-Day. But his death symbolized something larger, the end of static defense as a viable military strategy. The lesson was clear. In modern warfare, mobility defeats fortification. Air power defeats concrete. Industrial capacity defeats strategic position. The 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions fought for 33 more days after D-Day.

They held the line in the Kotantan Peninsula while the 4th, 9th, and 91st infantry divisions pushed north toward Sherborg. The fighting was brutal, hedge to hedro, field to field against German units that knew the terrain and fought with desperation. On June 18th, the 9inth Infantry Division reached the west coast of the Cottontown Peninsula, cutting off Sherborg from reinforcement.

The city, Normandy’s largest port, capable of handling 20,000 tons of supplies per day, was now isolated. The German garrison, 21,000 men under General Litnant Carl Wilhelm Fonbin, prepared for a siege. On June 22nd, American forces reached the outer defenses of Sherborg. Fon Schlleban had orders from Hitler to hold the city to the last man, to destroy the port facilities, to make Sherborg useless to the Allies even in defeat. He obeyed.

The harbor was mined. The cranes were demolished. The keys were blown up. The final assault began on June 25th. Three infantry divisions, the 4th, 9th, and 79th, supported by naval gunfire from battleships USS Texas, USS Arkansas, and HMS Glasgow attacked from three directions. The German defenders fought from fortified positions, from bunkers identical to those on the Atlantic wall, from concrete and steel that should have been impregnable.

But the Americans had learned the lesson of D-Day. They didn’t attack the fortifications head-on. They bypassed them. Infantry infiltrated through gaps. Engineers blasted paths with explosives. Tank destroyers fired point blank into embracers. And overhead, fighter bombers struck every German position that revealed itself. Sherbore fell on June 27th.

Von Schlleban surrendered with 800 men in an underground command post. The city was in ruins. The port was destroyed. But it was captured and American engineers, the same industrial capacity that had built the C-47s, the parachutes, the radios, began rebuilding it immediately. By mid July, Sherborg was operational.

By August, it was handling 12,000 tons of supplies per day. By September, 20,000 tons. The Atlantic Wall, which was supposed to prevent the Allies from capturing a port, had delayed them by 3 weeks. 3 weeks against an industrial machine that could rebuild a destroyed harbor faster than the Germans could fortify a coastline.

The 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions were withdrawn to England on July 13th. They had jumped into Normandy with 13,000 men. They left with 7,800, 40% casualties, killed, wounded, missing. the highest loss rate of any American division in the Normandy campaign. But they had accomplished their mission. The Atlantic Wall was breached. The beach head was secured.

The road to Germany was open. In the end, the Atlantic Wall cost Germany 2 years of construction. Billions of Reichsarks, the labor of millions of workers, French, Belgian, Dutch, forced laborers from across occupied Europe. It stretched 2,400 m from Norway to Spain, 6 and a half million mines, thousands of bunkers, hundreds of thousands of obstacles, and it was defeated in 90 minutes by 13,000 men dropping from the sky.

The lesson wasn’t lost on military strategists. After D-Day, no major power would rely on static defenses alone. The future belonged to mobility, air power, and the industrial capacity to deploy both at scale. The Atlantic Wall became a monument to a way of war that was already obsolete. General Major Wilhelm, killed at 4:00 hours on June 6th, 1944, never saw that future, but he experienced its arrival.

In the darkness of a Norman road, surrounded by American paratroopers who had fallen from the sky behind his defenses, he understood too late that the war had changed and Germany had already lost.