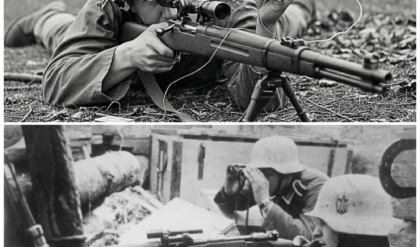

November 14th, 1943. 0530 hours. Bugenville Island, Solomon Islands. Staff Sergeant Thomas Arthur Caldwell pressed his body deeper into the volcanic soil. The Springfield 03 rifle steady against his shoulder. Through the Unertle 8 power scope, he watched a Japanese soldier 280 yards distant carefully light a cigarette. The brief flare of the match illuminated the man’s face for exactly 2.3 seconds.

It would be his last cigarette. What the Japanese soldier didn’t know was that he faced a sniper who had spent three weeks studying Japanese smoking habits with scientific precision. Sergeant Caldwell had logged over 400 observations in a waterproof notebook. Time of day when soldiers smoked. Duration of cigarette breaks.

how they cup their hands around matches, everything. The Japanese smoking culture was predictable as clockwork. They smoked after meals, during guard changes, before attacks, and constantly when stressed. Most importantly, they smoked in the same spots at the same times, creating patterns that could be exploited with mathematical precision.

Through his scope, Caldwell watched the soldier take his second drag. The cigarette’s ember glowed in the pre-dawn darkness like a beacon. Caldwell had already calculated windage, elevation, and the bullet’s 2.7 second flight time. His breathing slowed. His heart rate dropped to 42 beats per minute. The world narrowed to the reticle and the target. The shot broke clean.

The 190 grain bullet left the barrel at 2,800 ft pers. The soldier collapsed. Kill number 67. 25 more to go in the next 3 days. Over the next 96 hours, Sergeant Thomas Caldwell would transform smoking a cigarette into a death sentence for 92 Japanese soldiers.

His technique, later classified as the cigarette trick by Marine Corps intelligence, would be studied and employed by American snipers throughout the Pacific War and beyond. The true impact went far deeper than body count. It represented a fundamental shift in how modern snipers thought about their craft. Before Caldwell, snipers waited for targets. After Caldwell, they learned to create the conditions that made targets appear.

The cigarette trick was about understanding human behavior so thoroughly that you could predict, manipulate, and exploit it with lethal precision. Thomas Caldwell’s road to Buganville began on a tobacco farm in Madison County, North Carolina. Born March 7th, 1921, he grew up where cash crop cultivation defined existence.

By age 12, Thomas could identify tobacco varieties by leaf alone. More significantly, he had spent thousands of hours watching tobacco auctioneers and buyers communicate through subtle gestures. Thomas learned to read body language with extraordinary precision, a skill that would prove invaluable to a sniper.

His shooting education began at age seven when his grandfather gave him a .22 rifle. His grandfather’s instruction was profound. A rifle is a tool. Understand the rifle. Understand the target. Understand yourself. Only then do you squeeze the trigger. By age 16, Thomas was winning shooting competitions. At age 17, he shot a perfect score at 600 yards using iron sights, attracting attention from a Marine Corps recruiter who told him about Scout Sniper School and missions that required patience, intelligence, and extraordinary shooting skills.

December 7th, 1941 changed everything. Thomas enlisted on December 10th. His drill instructor noted in his service record, “Recruit demonstrates exceptional marksmanship ability and unusual capacity for remaining motionless for extended periods. Recommend sniper evaluation.” Thomas arrived at Scout Sniper School at Camp Leune in February 1942.

He excelled immediately. His tobacco farm background provided unexpected advantages. Hours in tobacco barns taught him to tolerate discomfort. Watching for tobacco hornw worms trained his pattern recognition. Years of reading human behaviors at tobacco auctions developed an almost supernatural ability to predict what people would do next. Captain Richard Bradford wrote in Thomas’s graduation report.

Private first class Caldwell demonstrates the finest natural sniper aptitude I have witnessed in 23 years. This marine will kill many enemies. Thomas graduated top of his class in June 1942 and received orders to the first Marine Division Scout Sniper Platoon. The target was Guadal Canal, August 7th, 1942. Guadal Canal.

Thomas’s combat initiation came at the Battle of Teneroo River on August 21st. He fired 63 times that night, achieving 47 confirmed kills. The experience taught him that precision meant everything. Every shot had to count. During the 4-month Guadal Canal campaign, Thomas logged 137 confirmed kills. Most importantly, he began noticing Japanese smoking habits. They smoked constantly.

Cigarettes were in their rations, 200 per month per man. They smoked before attacks, after attacks, during guard duty. and they were extraordinarily predictable about where and when they smoked. Thomas began documenting these patterns in November 1942. Using a waterproof notebook, he logged Japanese smoking behavior.

Two soldiers smoking near the Matanaka River. Same position three mornings straight. Single soldiers smoking behind the same tree daily. Officer at a trail junction. Fourth consecutive morning. same location. The patterns were undeniable. Thomas realized if he could predict where and when soldiers would smoke, he could preposition for perfect shots.

The cigarette became a timing device. When the ember glowed, the target was stationary and focused on the cigarette, not threats. By December, Thomas had begun deliberately exploiting these patterns. 29 of his 32 kills that month involved soldiers who were smoking. His shot tokill ratio improved to 1.3 to1.

The cigarette trick was being born. Following Guadal Canal’s conclusion in February 1943, Thomas was reassigned to division headquarters. Major Bradford requested Thomas specifically to formalize his techniques into training doctrine. For three months, Thomas developed sniper training materials.

His most significant contribution was a 16page manual titled Exploitation of Enemy Behavioral Patterns for Sniper Operations. The manual detailed smoking pattern research, included timing data, and explained how cigarette glow could be used for range estimation. Most controversially, it suggested techniques for encouraging enemies to smoke in locations advantageous to snipers.

Thomas’s response to concerns about fairness was direct. War is not sport. If predictable behavior creates vulnerability, exploiting that vulnerability is good tactics. The goal is victory achieved through minimum friendly casualties. The manual was approved and distributed. Thomas, promoted to sergeant, received orders to train the Third Marine Division’s Scout Sniper platoon before deploying to Buganville.

If you’re enjoying this deep dive into one of World War II’s most innovative sniper techniques, make sure to subscribe to the channel and hit that notification bell. We bring you the untold stories of warfare that changed history. Stories you won’t find anywhere else. Bugenville was larger, more mountainous, and more heavily garrisoned than Guadal Canal. Intelligence estimated 17,000 Japanese troops.

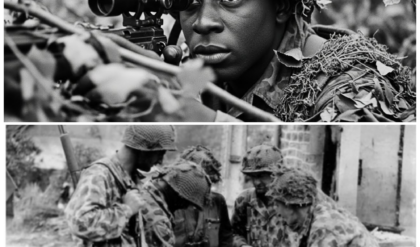

Thomas’ scout sniper section consisted of 12 men, all trained to his standards. Each carried a Springfield 03, 300 rounds of matchgrade ammunition, and a waterproof notebook for recording observations. The landing occurred November 1st. Between November 2nd and 10th, Japanese forces launched six major assaults. All failed.

The Marines established a defensive perimeter. Thomas’ section operated along the northern edge. He spent the first week exclusively observing. No shooting, only watching and recording. Thomas cataloged Japanese activity, identifying 37 locations where soldiers regularly smoked. Smoking occurred most frequently during six time windows, pre-dawn, post breakfast, midday, late afternoon, post dinner, and late evening.

Thomas identified patterns down to individual soldiers. One officer smoked exactly four cigarettes daily at the same rock outcropping. Thomas observed him for 7 days, timing varying by no more than 5 minutes. Another soldier smoked behind the same tree every morning at 0545. Six mornings. The pattern never varied. Thomas compiled this intelligence into detailed maps and schedules.

He knew where Japanese soldiers would be and when. November 14th would mark the beginning. The plan was methodical. Target soldiers in sequence, moving geographically through his sector. Shoot only during windows when natural sounds would mask his rifle’s report. Fire no more than three shots from any position before displacing. Most importantly, target only soldiers engaged in smoking.

This last criterion was crucial. By exclusively targeting smokers, Thomas would create psychological terror. Japanese soldiers would associate smoking with death. Some would try to quit, degrading combat effectiveness through withdrawal. Others would smoke but be constantly anxious, destroying alertness. The cigarette trick was psychological warfare as much as physical elimination.

November 14th, 0530 hours. Thomas’s first target was the private who smoked behind the same tree every morning. Thomas had positioned himself 280 yards distant the previous night, lying motionless for 7 hours in a prepared hindsight covered with local vegetation. Through his scope, Thomas watched the soldier emerge and walked to the familiar tree.

The man looked around briefly, then relaxed. He withdrew a cigarette and matches. The match flared. The soldier cupped his hands, head bent forward, completely vulnerable. The Springfield barked once. The bullet struck precisely below the soldier’s left eye, passing through the brain stem. Death was instantaneous.

kill 67. By midday, November 14th, Thomas had achieved six kills, all involving soldiers smoking, each shot from a different position. Each position selected days in advance. The Japanese began noticing something wrong. Bodies found near smoking locations. The pattern was obvious. By evening, officers were ordering men not to smoke during daylight. November 15th brought accelerated operations.

The no smoking order drove soldiers to smoke at night, believing darkness provided safety. Thomas had prepared for this. Between 1900 hours November 15th and 0600 hours November 16th, he achieved 14 kills, all involving soldiers smoking in darkness. The technique was simple. Thomas would watch until he saw a cigarette ember.

He would wait until the soldier took a drag, causing the ember to glow brightly. That glow provided 1 to two seconds of illumination, showing the target’s exact head position. Thomas would aim approximately 8 in below the ember and fire. The technique worked with devastating consistency. Japanese forces on Bugenville were experiencing something unprecedented, an invisible enemy killing them whenever they smoked.

The psychological impact spread rapidly. Soldiers refused to smoke. Others smoked only inside fortifications. Some tried lying on their backs while smoking. None of these counter measures worked. Thomas adapted and continued killing. By evening, November 16th, Thomas had achieved 31 kills in 53 hours. His rifle barrel needed rest.

The armorer declared it needed 24 hours to prevent accuracy degradation. Thomas used November 17th for reconnaissance. His reconnaissance revealed Japanese counter measures were evolving. Officers smoking only inside fortified positions. Enlisted men smoking in groups. Some had stopped smoking entirely.

Thomas adapted. If they smoked in groups, he would target groups. If they smoked in fortifications, he would wait for them to emerge. November 18th marked the campaign’s climax. Thomas identified 12 high-value targets, Japanese officers or NCOs, who continued smoking. Between 0500 and 2100 hours, Thomas engaged all 12. 11 died.

The 12th escaped with a grazing wound. By day’s end, Thomas’s total reached 87 confirmed kills. November 19th, 0500 hours. Thomas occupied a hide site overlooking a Japanese assembly area. Intelligence suggested a company-sized attack would launch at dawn. Through his scope, he watched soldiers preparing equipment and smoking frantically, knowing they might die in the coming attack.

In 43 minutes, Thomas fired seven times, achieving five kills and two solid hits. Each target was smoking when shot. By 0543, Japanese officers were screaming at soldiers to stop smoking. The attack launched at 0600 hours and was repulsed with heavy casualties. Thomas’s final tally for the 4-day period was 92 confirmed kills. Every single kill involved a target who was smoking or had smoked within 2 minutes.

The concentration of lethality represented one of the highest sniper body counts in such a compressed time frame in United States military history. More significantly, it validated the cigarette trick as legitimate doctrine. The psychological impact extended far beyond 92 dead soldiers. Postwar interviews with Japanese prisoners revealed the sniper attacks created widespread terror.

Soldiers developed elaborate rituals to avoid smoking in open areas. Some crushed cigarettes to powder and ate them for nicotine. Others traded cigarettes for food. The impact on morale was substantial and measurable. Major Bradford ordered Thomas to write a comprehensive afteraction report.

The resulting document, systematic exploitation of habitual enemy behavior, became required reading for all Marine Corps Scout Sniper Units. The report ran 37 pages. Thomas had documented that Japanese soldiers smoked an average of 8.3 cigarettes per day. Peak smoking times were after waking, after meals, and during stress. Soldiers were most vulnerable while lighting cigarettes, requiring both hands and focusing on the flame. Average time from match strike to fully lit was 4.

7 seconds, during which the soldier was stationary. Thomas’s recommendations for future operations included identify smoking patterns through minimum two weeks observation. Create detailed maps showing locations and times. Prioritize targets based on rank. Vary shooting positions. Use natural sounds to mask reports. Create psychological pressure by exclusively targeting smokers.

And document everything for analysis. The report concluded with a statement quoted in sniper training for decades. The cigarette trick exploits the intersection of physiology, psychology, and predictable human behavior. Nicotine addiction creates patterns that cannot be easily modified even when danger is recognized.

By understanding and exploiting these patterns, snipers can achieve lethality far exceeding their numerical strength. Marine Corps leadership embraced the cigarette trick enthusiastically. By early 1944, Thomas was conducting training courses for scout sniper units throughout the Pacific. The techniques employment expanded rapidly. On Guam, Marine snipers claimed 137 kills in the first week.

On Pleu, it accounted for approximately 20% of all sniper kills. On Euoima, Marines would deliberately leave cigarette packs where Japanese soldiers would find them baiting traps with tobacco. The army’s infantry divisions adopted it as well. By mid 1945, the cigarette trick was standard doctrine taught to all American snipers deploying to the Pacific. Japanese forces attempted countermeasures.

Orders forbidding daylight smoking proved uninforcable. Attempts to smoke only inside fortifications failed when Marines destroyed smoking positions after snipers identified them. Some units tried synchronized smoking, having all soldiers light up simultaneously. This failed because snipers would simply shoot the highest ranking soldier visible, then rotate positions.

The most effective counter measure was complete cessation. But this proved psychologically impossible. Nicotine addiction combined with combat stress made smoking a physiological necessity. Most soldiers chose to smoke and accept the risk. Postwar analysis suggests the cigarette trick accounted for between 3,000 and 5,000 Japanese casualties throughout the Pacific War.

This includes both direct sniper kills and indirect casualties from psychological stress and reduced effectiveness among nicotine-deprived soldiers. After Bugganville, Thomas participated in campaigns on Guam and Bleu, achieving an additional 73 confirmed kills. His total confirmed count reached 347, making him one of the most lethal American snipers of World War II.

Approximately 40% of those kills, 139, involved the cigarette trick. In September 1945, Gunnery Sergeant Thomas Caldwell returned to the United States. He received the Navy Cross for his actions, the citation reading, “For extraordinary heroism as a scout sniper.” Gunnery Sergeant Caldwell displayed exceptional courage, initiative, and tactical brilliance.

His innovative techniques and consistent lethality contributed significantly to Marine operations and saved countless American lives. Thomas left the Marine Corps in December 1945 and returned to North Carolina. He never spoke publicly about his service, declining interviews.

He married in 1947, raised four children, and operated a tobacco farm until retirement in 1986. Those who knew him described a quiet, thoughtful man who rarely discussed the war. If you’ve made it this far, you’re clearly fascinated by the tactical innovations that shaped modern warfare. Subscribe now so you don’t miss our upcoming episodes on the hidden weapons and techniques that changed military history forever.

The cigarette tricks influence extended far beyond World War II. During Korea, American snipers employed variations against Chinese and North Korean forces who also smoked heavily. In Vietnam, snipers adapted the technique for night operations using starlight scopes to detect cigarette embers at distances exceeding 1,000 yards.

Marine sniper Carlos Hathcock, who studied Caldwell’s writings, employed variations to achieve approximately 30 of his 93 confirmed kills. Modern military forces continue studying the cigarette trick as a case study in pattern recognition and behavioral exploitation. United States Army Sniper School includes it in curriculum as an example of understanding enemy habits to create tactical advantages. Students learn to identify, document, and exploit any predictable enemy behavior.

The technique also influenced civilian law enforcement sniper doctrine. Police tactical teams learned to study subject behavior patterns to predict actions. The principle that humans are creatures of habit became foundational to modern sniper training across military and law enforcement. Thomas Caldwell died on March 2nd, 2009 at age 87.

His obituary made no mention of his military service beyond noting he was a World War II veteran. The Marine Corps History Division published a more complete obituary recognizing his contributions. At his funeral attended by over 300 people, including 12 former Marine snipers, Master Gunnery Sergeant Michael Torres delivered a eulogy capturing Thomas’s legacy. Gunny Caldwell taught us that sniping isn’t just marksmanship.

its observation, pattern recognition, patience, and the ability to exploit enemy mistakes. He showed us that warfare is about understanding human nature. Every Marine sniper since 1944 owes Gunny Caldwell a debt. He taught us how to think. The cigarette trick represents a watershed moment in sniper doctrine development.

It demonstrated snipers could be proactive rather than reactive, creating conditions for successful engagements rather than waiting for targets. It proved psychological warfare and physical elimination could be combined into a single technique, degrading enemy effectiveness through terror as much as casualties. More fundamentally, it showed seemingly trivial habits could become fatal vulnerabilities.

Smoking, an act so routine it was barely conscious became a death sentence under the right circumstances. This forced military forces worldwide to rethink soldier training, emphasizing everything done in a combat zone must be done with tactical awareness. The 92 Japanese soldiers killed during those four days were victims of their own habits as much as American marksmanship.

They died because they smoked in predictable places at predictable times. They died because one Marine sniper had the intelligence to recognize patterns, the patience to document them, and the skill to exploit them with lethal precision. The cigarette tricks legacy continues shaping military operations today.

Satellites track enemy movement patterns, signals, intelligence maps, communication schedules. Analysts create predictive models of enemy behavior. All of this is conceptually identical to Thomas Caldwell documenting when and where Japanese soldiers smoked. The technology has changed. The principle remains the same.

Understand patterns, exploit patterns, win battles. In military museums across America, visitors can see Thomas Caldwell’s Springfield03 rifle, the Unertle scope he used, and the waterproof notebook containing his smoking pattern observations. These artifacts represent more than one man’s service. They represent a revolution recognizing warfare’s fundamentally human nature.

Soldiers have habits, needs, addictions, and predictable behaviors. Understanding and exploiting these human factors can be as important as understanding tactics and terrain. Today, when military instructors teach new snipers about intelligence preparation and pattern analysis, they often begin with Thomas Caldwell’s story.

They describe a Marine sergeant armed with a rifle, a scope, a notebook, and the patience to watch enemies for weeks before firing. They explain how he documented patterns, created targeting schedules, and systematically eliminated 92 soldiers by exploiting their nicotine addiction. They emphasize this is what separates good snipers from great ones.

Great snipers don’t just shoot well, they think brilliantly. The cigarette trick stands as proof that in warfare, knowledge is power. Thomas Caldwell’s knowledge of tobacco, human behavior, and enemy habits, combined with extraordinary marksmanship, and tactical innovation created a technique that killed thousands across multiple conflicts. His legacy lives on every time a sniper studies enemy patterns, every time a tactical unit analyzes behavioral intelligence, every time a military planner recognizes that understanding human nature is as important as

understanding weapons. 92 kills in 4 days. Each victim killed while engaging in an act they had done thousands of times before. Each death a reminder that predictability is fatal. Each casualty proof that one innovative sniper can terrorize an entire enemy division. The cigarette trick worked because Thomas Caldwell understood something fundamental. Humans are creatures of habit.

Those habits can be studied. Those habits can be predicted and in war those habits can be exploited with lethal consequences. The Japanese soldiers on Bugganville who died smoking cigarettes in November 1943 never knew what killed them. They died instantly. Most never hearing the shot.

But their death sent a message echoing through Japanese forces across the Pacific. Nowhere is safe. Nothing is routine. Every action has consequences. Even lighting a cigarette can be fatal when an American sniper is watching. That message delivered through 92 precisely aimed bullets over four days represent psychological warfare at its most effective.

It changed how Japanese soldiers thought about basic daily activities. It introduced doubt and fear into the simplest acts. It made men paranoid about habits they couldn’t break. Thomas Caldwell’s cigarette trick stands as one of World War II’s most innovative tactical developments. Born from unlikely origins on a North Carolina tobacco farm, refined through systematic observation and employed with devastating effectiveness, it proves snipers could be more than marksmen.

They could be intelligence gatherers, behavioral analysts, psychological warfare specialists, and force multipliers whose impact far exceeded their numbers. One sergeant with a rifle killed 92 enemies in 4 days. More importantly, he terrorized thousands into reduced effectiveness and created doctrine continuing to shape sniper operations 80 years later.

The next time you see someone light a cigarette, remember those Japanese soldiers on Bugganville. They performed that same simple act, never realizing it would be their last. They died because one Marine had the insight to recognize their habit was their weakness and the skill to exploit that weakness with mathematical precision.

They died because Thomas Caldwell understood that sometimes the deadliest weapon isn’t the rifle. It’s the knowledge of when and where to aim it. They died because they were predictable. And in war, predictability is always fatal.