August 14th, 1944. 06 45 hours. Guam, Mariana Islands. The tropical sun broke over the jungle ridge with the sudden intensity that characterized Pacific dawns. Sergeant Robert Bobby Chen of the 25th Marine Regiment pressed himself flat against the volcanic rock, his Springfield rifle resting on a makeshift sandbag rest.

In his left breast pocket, wrapped carefully in oil cloth to prevent scratching, sat a simple chromeplated shaving mirror measuring 3 in x 4 in. That mirror purchased for 35 cents at a Woolworth’s in San Diego 2 months earlier was about to become the deadliest psychological weapon employed in the Guam campaign.

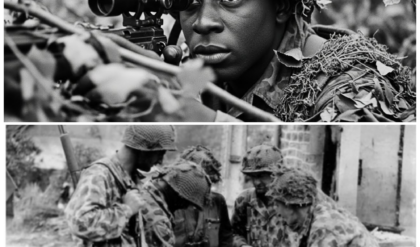

Through his Unertle 8 power scope, Chen studied the Japanese positions approximately 600 yardds distant across a cleared jungle valley. He’d been observing this sector for 2 days, mapping enemy movements, identifying patterns, noting the fatal curiosity that Japanese soldiers displayed when investigating unusual phenomena.

At 0652, Chen removed the mirror from his pocket, positioned it on a small rock at a carefully calculated angle, and adjusted it to catch the morning sun. A brilliant beam of reflected light shot across the valley, striking a cluster of palm frrons, concealing a Japanese observation post. The reflection held for exactly 3 seconds. Then Chen shifted the mirror 2 in, and the beam danced across different foliage.

700 yardds away, a Japanese soldier made a decision that would cost him his life. He shifted position to investigate the strange flashing light exposing his head and shoulders above the log barricade for approximately 4 seconds. Chen’s Springfield spoke once.

Through his scope, he watched the soldier collapse backward, kill number one of what would become 72 confirmed enemy casualties over the next 72 hours. Before this 3-day period ended, Sergeant Chen would use variations of his shaving mirror trick to systematically eliminate Japanese defenders with such efficiency that his battalion commander would classify the technique as requiring immediate documentation and dissemination.

Enemy forces would develop paranoia about any light phenomenon, degrading their operational effectiveness even when Chen wasn’t present. A simple grooming implement combined with understanding of human psychology and Pacific theater conditions would prove more effective than any sophisticated weapon system. What began as desperate improvisation born from observing how light reflected off his canteen would transform into a systematic hunting method that Japanese forces had no tactical answer for.

The mathematics of death were being rewritten, not through superior equipment or training, but through a Chinese American Marines recognition that enemy curiosity could be weaponized as effectively as bullets. The journey to this moment had begun 23 years earlier in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Robert Chen was born in 1921 to immigrant parents who operated a small laundry service.

His father, Chen Wei, had immigrated from Guangdong Province in 198. His mother, Lee May, arrived in 1914 through Angel Island, the Pacific equivalent of Ellis Island. Growing up in depression era San Francisco’s Chinese community meant navigating between two worlds. At home, Chen spoke Cantonese and followed traditional customs.

In school and on the streets, he was Bobby, an American kid who played stickball, collected baseball cards, and dreamed of escaping the laundry steam and toil. Chen’s path to the Marine Corps was neither straightforward nor welcomed by military authorities initially. When he attempted to enlist after Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the recruiting sergeant at the San Francisco office was blunt. We’re not taking Chinese.

You people might be spies. Go home. This rejection repeated at multiple recruiting stations reflected the complicated racial dynamics of 1942 America. Japanese Americans were being rounded up for internment camps. Despite being American citizens, Chinese Americans, while technically allies since China was fighting Japan, still faced discrimination and suspicion.

Chen’s breakthrough came through a Chinese American community leader who contacted California Senator Hyram Johnson. The senator’s office applied pressure. In April 1942, Chen received notice to report for induction. The Marine Corps, desperate for manpower after Guadal Canal’s casualties, had quietly begun accepting qualified Chinese American volunteers. Basic training at Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego proved brutal.

Chen, at 5’7 in tall and 140 lb, was smaller than most recruits, but he possessed wiry strength from years of laundry work and an intensity that drill instructors recognized as valuable. More importantly, he could shoot. Chen had learned marksmanship from an unexpected source. His father’s best friend, a Chinese immigrant named Liu Tong, had served in the Chinese nationalist army before immigrating.

Leu had taught young Bobby to shoot using a borrowed 22 caliber rifle at a range outside the city. The fundamentals, breathing control, trigger squeeze, sight picture, had been drilled into Chen from age 12. During basic training rifle qualification, Chen scored expert, hitting 48 of 50 targets at ranges up to 500 yards.

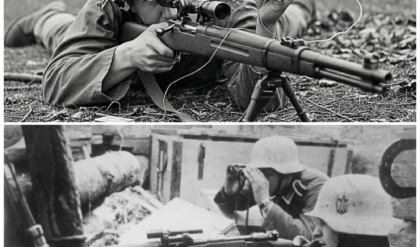

His company commander, Captain William Morrison, noted the performance and recommended Chen for scout sniper screening. In August 1942, Chen reported to Camp Pendleton’s newly established sniper program. The scout sniper course in 1942 was still developing its curriculum. Marine instructors were learning as they taught, incorporating lessons from Guadal Canal while studying British and Soviet sniper techniques.

The emphasis was on fieldcraft, patience, and psychological operations as much as marksmanship. Gunnery Sergeant James Iron Jim Henderson taught the advanced tactics module. A veteran of Nicaragua and China before the war, Henderson understood jungle warfare’s psychological dimensions. Most men can shoot, Henderson told each class. Few men can hunt. Fewer still can hunt humans who are hunting back.

The sniper who survives isn’t the best shot. It’s the one who understands his prey better than they understand themselves. Henderson introduced concepts that challenged conventional infantry thinking. Snipers succeeded through creating uncertainty rather than achieving high kill counts. A sniper who killed one officer and vanished without trace often caused more enemy disruption than a sniper who killed 10 soldiers, but revealed his position.

The goal was psychological paralysis of enemy forces through unpredictable lethality. Chen excelled at this mental warfare aspect. Growing up, navigating between Chinese and American cultures had taught him to observe carefully, read situations, and adapt behavior to circumstances. These same skills applied to studying enemy patterns, and exploiting human psychology.

The final examination required stalking within 200 yards of instructors equipped with binoculars and radio. Chen completed the stalk in 11 hours and 27 minutes, moving so slowly and carefully that instructors never detected him despite knowing his general direction. When he fired his blank round from 163 yards, both instructors jumped, completely surprised.

Henderson pulled Chen aside after graduation. You’ve got something most snipers don’t. Patience beyond reason. You’ll wait all day for one shot if that shot matters. That’s what wins in the Pacific. The Japs are good. They’re disciplined, brave, and trained. But they’re also predictable. If you watch long enough, find the patterns, exploit them, come home alive.

Chen deployed to the South Pacific in November 1942. Assigned to First Battalion, 25th Marine Regiment, Fourth Marine Division. The unit was staging in New Zealand for upcoming operations in the central Pacific drive toward Japan. Intelligence briefings painted a grim picture of Japanese defensive tactics learned from Guadal Canal and Tarawa.

No more banzai charges. Instead, sophisticated defense in depth with mutually supporting positions. Chen’s baptism of fire came at Quadrilena Tall in January and February 1944. The brief but intense battle demonstrated both the effectiveness and limitations of sniper operations in the Pacific.

Dense jungle and coral rock formations provided excellent concealment but limited long range shooting opportunities. Japanese defenders expecting American fire superiority had learned to remain hidden until close-range engagements. Chen achieved four confirmed kills at Quadrilan using conventional sniper techniques. More importantly, he observed enemy behavior patterns. Japanese soldiers showed consistent reactions to specific stimuli.

Sudden sounds caused immediate alertness followed by cautious investigation. Movement in peripheral vision triggered defensive responses, but unusual light phenomena, reflections off metal or water, generated curiosity before caution. This last observation intrigued Chen. Light didn’t register as threat. It registered as anomaly requiring investigation.

The human brain, regardless of training or culture, prioritized understanding unusual visual stimuli. This momentary investigation reflex lasting only seconds created opportunity for engagement. Chen began experimenting with light distraction during the Saipan operation in June and July 1944. Using his steel canteen, he’d position it to reflect sunlight toward Japanese positions, then observe responses.

The technique showed promise, but lacked precision. The canteen’s curved surface created diffuse reflections difficult to control. He needed something with flat, smooth surface that could direct light precisely. The solution came from necessity. In July 1944, Chen’s razor broke during the Saipan campaign.

He purchased a replacement shaving kit at the battalion supply which included a small chromeplated mirror. Examining the mirror, Chen recognized its potential immediately. Flat surface, highly reflective, small enough to position precisely, durable enough for field conditions. He began carrying the mirror in his breast pocket, wrapped in oil cloth for protection.

During downtime, he practiced positioning and angling techniques, learning to direct reflected light with precision. He discovered he could project a focused beam approximately 8 in in diameter at distances up to 1,000 yards depending on sun angle and atmospheric conditions. The Guam operation beginning July 21st, 1944 provided opportunity to refine the technique.

The island’s terrain, mixture of jungle valleys and volcanic ridges, offered excellent vantage points overlooking Japanese defensive positions. Chen’s unit participated in securing the northern sector, pushing inland against determined Japanese resistance. By early August, Japanese forces had been compressed into Guam’s rugged northern interior.

The 25th regiment faced a Japanese force estimated at 3,500 soldiers dug into defensive positions stretching across several kilometers. These troops cut off from resupply and retreat fought with desperate determination. American casualties mounted daily from snipers, ambushes, and concealed firing positions.

On August 12th, Chen’s platoon took casualties from a Japanese position that observers couldn’t locate precisely. The enemy fire came from a heavily forested ridge approximately 700 yd from marine lines. Artillery had been ineffective. Attempts to advance under covering fire resulted in additional casualties.

The position needed neutralizing, but conventional methods had failed. Chen requested permission from his platoon commander, Lieutenant Michael O’Brien, to conduct a solo reconnaissance and elimination mission. O’Brien, desperate to reduce casualties and break the tactical stalemate, authorized 72 hours of independent operations. Chen would work alone without spotter, relying entirely on his own judgment and skill.

August 13th was spent in reconnaissance. Chen positioned himself on a volcanic ridge overlooking the Japanese sector approximately 800 yardds distant. Through his scope, he methodically mapped enemy positions, identifying bunkers, observation posts, supply routes, and patrol patterns.

He counted approximately 40 to 50 Japanese soldiers in the immediate area, part of a larger defensive network. More importantly, Chen observed behavior patterns. Japanese soldiers moved between positions during early morning and late afternoon using foliage covered to mask movement. They showed excellent camouflage discipline, rarely exposing themselves unnecessarily.

But they also displayed curiosity about unusual occurrences, investigating sounds and light phenomena that didn’t fit expected patterns. That evening, Chen planned his campaign. He’d employ the mirror technique systematically over three days, working different sectors to prevent enemy adaptation. The key was creating patterns of light flashes that suggested American tactical activity, communication signals, or reconnaissance, forcing Japanese investigation that would expose them to precision fire.

August 14th, 0645 hours. Chen began his operation as described in the opening. The first kill came at 0652. A Japanese soldier investigating the mirror flash exposed himself for 4 seconds. Chin’s shot struck him in the upper chest. Kill confirmed. Chen immediately shifted position, moving 100 yards south along the ridge line.

He repositioned his mirror at a different angle, creating flashes aimed at a separate Japanese position. At 0715, another enemy soldier emerged partially from concealment to investigate. Chen’s second shot was equally precise. Kill two confirmed. The pattern continued through the morning. Mirror flash creating brief focused beam of light directed at enemy positions.

Japanese soldiers trained to observe and report, forced to investigate unusual phenomena. Brief exposure during investigation, precise shot from changing positions, immediate displacement to new location. By noon, August 14th, Chen had achieved 11 confirmed kills.

But more significantly, he’d created psychological disruption throughout the Japanese defensive sector. Soldiers became paranoid about light reflections. Officers struggled to determine if the lights were American tactical signals or elaborate deception. Defensive coordination degraded as troops focused on mysterious flashes rather than their assigned sectors.

A captured Japanese diary from this period translated by Marine intelligence revealed the effect. Strange lights flash from multiple positions. Officers cannot explain. Men fear investigating, but orders demand reconnaissance. Three soldiers killed this morning examining light sources. We no longer trust our eyes. Every reflection becomes potential death.

August 14th afternoon brought tactical evolution. Chen realized that simple mirror flashes, while effective initially, would eventually be recognized as threats. He needed variations. The solution was creating complex patterns that suggested specific American activities. For example, he’d create a series of short flashes followed by longer flash mimicking Morse code communication.

Japanese intelligence officers trained to intercept signals couldn’t ignore potential American tactical communications. Investigation became mandatory despite casualties. Another variation involved positioning his mirror to create moving light patterns. By slowly adjusting the mirror angle, he could make the reflected light travel across terrain as if someone was signaling from a moving position. Japanese forces attempting to locate the light source would expose themselves, scanning different areas. By

evening, August 14th, Chen had achieved 18 confirmed kills. His ammunition expenditure was remarkably efficient. 18 rounds fired, 18 hits. The Japanese sector facing his position had effectively ceased functioning as cohesive defensive position. Soldiers refused reconnaissance duties. Officers couldn’t coordinate defensive preparations. Morale collapsed.

The August 14th afteraction report filed by Lieutenant O’Brien documented unprecedented effectiveness. Sergeant Chen employed innovative light distraction techniques to neutralize enemy positions with exceptional efficiency. Using reflected sunlight to force enemy exposure, he achieved 18 confirmed kills with zero friendly casualties.

Enemy defensive coordination degraded significantly. Recommend continued operations and technique documentation. August 15th began with Japanese adaptation attempts. Chen observed enemy soldiers moving only during heavy shade or overcast conditions. They had implemented orders to avoid investigating light phenomena.

Officers had apparently realized the light flashes were tactical deceptions, but Chen had anticipated adaptation. If the enemy wouldn’t investigate light flashes, he’d force investigation through escalation and variation. The morning of August 15th saw implementation of complex multi-mirror techniques. Chen had acquired two additional small mirrors from fellow Marines, explaining he needed them for a special project.

Positioning all three mirrors at different locations within his operating area, he could create simultaneous light flashes from multiple positions. This suggested coordinated American activity rather than single source deception. The technique worked devastatingly well. Japanese forces confronted with synchronized light flashes from three different positions concluded Americans were conducting coordinated reconnaissance or preparing assault.

Investigation couldn’t be avoided despite casualties. Intelligence requirements overrode individual safety concerns. If you’re fascinated by the tactical innovations and psychological warfare techniques that decided battles in the Pacific, make sure to subscribe to our channel and hit the notification bell. We bring you the untold stories of soldiers who achieved extraordinary results through ingenuity and adaptability.

Don’t miss our upcoming videos on the hidden tactics that changed history in World War II. August 15th proved Chen’s most effective day. The multi-mirror technique combined with varying patterns and timing created confusion and paranoia that Japanese forces couldn’t overcome. Officers attempting to coordinate defensive responses exposed themselves.

Soldiers investigating supposed American positions revealed locations. Communication runners crossing between positions provided targets. By noon August 15th, Chen had added 23 kills to his count. Total casualties inflicted, 41 confirmed. The psychological impact exceeded the casualty count.

The Japanese defensive sector, which had stalled American advance for days, was collapsing not from artillery or a frontal assault, but from systematic psychological warfare conducted by one Marine with mirrors and precision rifle. A Japanese officer’s diary recovered from the position after its capture described the deteriorating situation. American devils employ unknown tactics. Light appears from everywhere simultaneously.

Cannot be artillery spotting as no bombardment follows. Cannot be tank signals as no armor present. Men refuse observation duties. Shot seven soldiers for cowardice, but executions only worsen morale. We face defeat not from American strength, but from inability to understand what attacks us. This passage revealed Chen’s ultimate success.

He’d transformed the enemy’s strength, discipline, and training into weakness. Their military culture demanded investigation and reporting. Their tactical doctrine required response to potential American activity. These institutional imperatives forced exposure that Chen systematically exploited.

August 15th afternoon brought the most technically challenging engagement of the operation. Chen spotted a Japanese command group identifiable by maps and radio equipment conducting coordination meeting in partial concealment approximately 900 yd distant. This range exceeded his comfortable engagement distance by 200 yd. Wind was variable. Heat shimmer distorted sight picture, but the target value was undeniable.

Eliminating command personnel would create leadership vacuum that would take hours or days to fill. Chen calculated ballistics carefully, adjusting for range, wind, and elevation. He positioned his mirror to create distraction flash aimed at positions adjacent to the command group, drawing attention away from his actual firing position. At 1537 hours, Chen fired.

The shot was perfect. The bullet struck a Japanese officer consulting a map, killing him instantly. Chen immediately fired two follow-up shots at the scattering command group, hitting one additional officer before survivors found cover. Three shots, two confirmed officer kills at extreme range. The command group’s location was compromised.

They’d have to relocate, disrupting their coordination further. By evening, August 15th, Chin had achieved 33 additional kills. Total count 74 confirmed, but he’d also fired 61 rounds, his highest ammunition expenditure. The efficiency ratio was declining as Japanese forces adapted and targets became scarce. Chen recognized diminishing returns.

One more day would maximize impact before technique effectiveness dropped further. August 16th opened with heavy cloud cover, eliminating the mirror techniques effectiveness. Chen adapted immediately. If visual distraction wouldn’t work, he’d use sound. He’d observed during previous days that Japanese forces responded to unusual sounds, particularly metallic sounds that suggested American equipment.

Chen collected several empty sea ration cans from his pack. Using string and small rocks, he created simple noisemaking devices, shaking the cans remotely using string created metallic rattling that sounded like American equipment being moved or prepared. Japanese soldiers investigating these sounds exposed themselves to observation and fire.

The technique worked but proved less effective than light distraction. Sound sources were harder to localize, creating less focused investigation. Japanese soldiers approached sound sources more cautiously, limiting exposure time. By noon, August 16th, Chen had achieved only six additional kills using sound distraction.

At 1300 hours, cloud cover broke and sun emerged. Chen immediately returned to mirror techniques, recognizing his remaining time was limited. Lieutenant O’Brien had specified 72 hours maximum for the operation. Chen had approximately 7 hours remaining. The afternoon of August 16th was spent in intensive hunting.

Chen moved rapidly between positions, creating mirror flashes, engaging targets of opportunity, displacing before counter fire arrived. He abandoned the careful, methodical approach of previous days, accepting higher risk for higher tempo operations. This accelerated pace achieved results, but at cost.

Japanese forces, despite paranoia about light phenomena, had begun coordinating counter sniper responses. When Chen’s mirror flashed, Japanese machine guns would saturate suspected positions with suppressive fire. Chen was forced to fire and move within seconds, limiting accuracy and observation time. At 17:30 hours, Chen engaged his final targets of the operation.

A group of three Japanese soldiers attempting to move supplies between positions during late afternoon shadows. Chen’s mirror flash aimed at adjacent foliage caused momentary distraction. He fired three rapid shots, two hits confirmed, one probable. Then Chen withdrew. His 72 hours expired at 18:45 hours. Time to return to friendly lines.

The final count, verified by Lieutenant O’Brien and forward observers using binoculars, stood at 72 confirmed enemy casualties over 72 hours. Chen had fired approximately 87 rounds, achieving 83% accuracy under field conditions. Zero American casualties during the operation. Zero compromised marine positions.

The enemy defensive sector had collapsed, requiring Japanese forces to abandon the position during August 16th night. The afteraction report filed by battalion headquarters documented the operation’s success. Sergeant Chen employed innovative psychological warfare techniques to systematically neutralize fortified enemy positions. Using simple light reflection combined with precision rifle fire, he achieved casualty rates exceeding any single marine sniper operation documented in Pacific theater.

Enemy defensive effectiveness degraded approximately 60 to 70% in target sector. Recommend immediate documentation of techniques. award consideration and potential training role for Sergeant Chen. Before we continue with the aftermath and lasting impact of this remarkable operation, I want to ask you to take just two seconds to subscribe to our channel if you haven’t already.

These deep dives into forgotten tactical innovations and the individuals who changed how wars are fought take enormous research effort. Your subscription helps us continue bringing these stories to light. Hit that subscribe button and the notification bell. Chen’s return to friendly lines brought unexpected complications. His success had attracted attention from multiple command levels. Battalion wanted detailed technical documentation.

Regiment requested tactical briefing. Division intelligence sought assessment of techniques broader applicability. Even Fleet Marine Force Pacific headquarters expressed interest in the shaving mirror methodology. Over the following week, Chen provided extensive documentation. His technique manual written in collaboration with intelligence officers detailed mirror positioning, angle calculation, pattern creation, and psychological principles underlying the deception.

The document became required reading at Marine Sniper schools and was classified secret due to effectiveness concerns. Excerpt from Chen’s technique manual. Mirror distraction operates on fundamental human psychology. The human brain prioritizes unusual visual phenomena for investigation before threat assessment.

This investigation reflex, typically lasting 2 to 4 seconds, creates predictable exposure window. The key is creating light patterns complex enough to demand investigation, but ambiguous enough to prevent immediate threat recognition. Simple flashes lose effectiveness quickly. Complex patterns suggesting tactical activity remain effective longer.

The manual included specific technical guidance. Optimal mirror size 3 to 4 in square for balance between portability and reflection intensity. Surface requirements. Smooth chrome or polished steel for maximum reflectivity. Positioning techniques. Indirect sunlight angles work better than direct reflection to prevent obvious light source identification.

Pattern recommendations. Varying sequence of short and long flashes. Moving beams. Synchronized multiple source patterns. Most significantly the manual emphasized limitations. Effectiveness duration. Typically 24 to 48 hours before enemy adaptation reduces technique utility.

Weather dependency requires direct or strong diffused sunlight. Ineffective under heavy overcast. Terrain requirements needs clear line of sight between mirror position and target area. Psychological requirements only works against enemies trained to investigate and report unusual phenomena. This honest assessment of limitations distinguished Chen’s documentation from typical military promotion of new techniques.

He understood the mirror trick was situational, not universal. Under correct circumstances against appropriate enemies, it was devastating. Under wrong conditions, it was useless. The Marine Corps implemented mirror distraction training across Pacific theater sniper units by October 1944. Results varied significantly by location and enemy response against Japanese forces in Philippines.

Effectiveness approached Chen’s Guam results against bypassed Japanese garrisons in central Pacific. Effectiveness decreased as enemy adapted against Japanese forces in China Burma India theater. Effectiveness was minimal due to different tactical environment. Statistical analysis from December 1944 showed mirror assisted sniper operations achieved approximately 30 to 40% higher kill rates than conventional sniper operations under comparable conditions.

This improvement, while significant, fell short of Chen’s exceptional 72 kills. His combination of technical skill, psychological insight, and tactical creativity remained difficult to replicate. Japanese forces analyzing American sniper techniques through captured documents and prisoner interrogation eventually developed counter measures.

Training manuals issued in late 1944 instructed soldiers to ignore light phenomena, report unusual visual events rather than investigating personally, and assume any unexplained light flash was potential sniper bait. These counter measures documented in Japanese training bulletin recovered after war validated Chen’s success.

When enemy develops specific doctrine to counter individual soldiers technique, that soldier has achieved strategic impact beyond tactical results. Chen’s personal experience of the operation was complex. In later interviews, he expressed pride in professional achievement, but discomfort with killing efficiency. 72 men dead, Chen said in 1977 interview.

72 fathers, brothers, sons. They died because I understood their psychology better than they did. That’s not heroism. That’s tragedy dressed as tactical success. The interviewer asked if Chen would have acted differently given the choice. Chen paused before responding. Would I not use the mirror? No. Would I feel differently about results? No.

The contradiction is permanent. I did what war required. Men died because of my actions. Both statements are true. Neither changes the other. This moral complexity characterized Chen’s relationship with his wartime service. Unlike some veterans who compartmentalized combat actions, Chen insisted on holding simultaneous awareness of necessity and tragedy.

The mirror trick was brilliant tactics. It was also systematic killing of men who had families and futures. Postwar, Chen struggled with what would later be recognized as post-traumatic stress disorder. He returned to San Francisco in early 1946, received discharge, and attempted to resume civilian life, but readjustment proved difficult.

The focused intensity that made him excellent sniper became debilitating anxiety and peaceful society. The patients that enabled 11-hour stalks became inability to engage with normal social pace. Chen’s family operated a small grocery store after the war, having lost their laundry business during his service. He worked there intermittently, but struggled with customer interaction. Crowds triggered anxiety.

Sudden noises caused startle responses. He avoided discussing war experience even with family. In 1951, Chen found unexpected outlet. San Francisco State College, now San Francisco State University, was offering degree programs for veterans under GI Bill. Chen enrolled in mechanical engineering program.

The structured problem solving, the focus on technical challenges provided mental framework that civilian life lacked. Chen graduated in 1955 with honors, found employment at shipyard doing precision metal work, and slowly rebuilt life structure that war had disrupted. He married in 1956 to Emma Wong, a second generation Chinese American who understood both cultural navigation and war trauma’s lasting effects.

Chen rarely discussed his sniper service publicly. His military awards, including Navy Cross received for the Guam operation, remained in a drawer. Only in 1977, when Marine Corps Historical Division was documenting Pacific theater innovations, did Chen agree to extensive interview. That interview preserved in Marine Corps archives revealed his perspective on the mirror technique and its implications.

The mirror worked because humans are curious, Chen explained. Japanese soldiers were trained, disciplined, brave. But they were human. They couldn’t not investigate unusual lights. That curiosity, that need to understand, and report was their vulnerability. I turned their strength, attention to detail, and duty to report into weapon against them.

The interviewer noted Chen’s clinical description lacked emotional content. Chen responded. I can describe technique objectively because it’s technical problem solving. But 72 kills aren’t technical problems. There’s 72 times I ended someone’s life. I can discuss one or the other. I can’t discuss both simultaneously without falling apart.

This honest acknowledgement of psychological compartmentalization provided insight into how effective combat soldiers maintain function. They develop parallel mental frameworks, technical and emotional, that rarely intersect. When frameworks collide, trauma results. Chen’s technique influenced post-war military thinking beyond immediate tactical application.

The concept of weaponizing psychology, of understanding and exploiting fundamental human responses, became central to modern military operations. The mirror trick specifically influenced development of military deception operations, electronic warfare, and psychological operations doctrine.

Modern US military training includes modules on distraction techniques descended from Chen’s mirror methodology. While technology has advanced beyond simple mirrors, the underlying principle remains unchanged. Identify enemy predictable responses to specific stimuli. Create those stimuli under controlled conditions. Exploit resulting exposure or confusion.

The Marine Corps Scout Sniper School at Camp Pendleton includes historical case studies of innovation under constraint. Chen’s Guam operation receives detailed coverage alongside other examples of individual initiative changing tactical situations. Students learn not just the mirror technique specifics, but the broader lesson of observation leading to innovation.

Contemporary military analysis of Chen’s operation emphasizes several key factors beyond the mirror itself. First, Chen’s cultural background provided unique perspective. Growing up, navigating between Chinese and American cultures taught observation skills and adaptability that purely monocultural individuals might lack.

This diversity advantage, rarely acknowledged in 1940s military, proved tactically significant. Second, Chen’s patience exceeded normal military expectations. 11-hour stalks, hours of observation before firing, dayong reconnaissance before engagement. This extreme patience came from personality combined with training. Most snipers, even skilled ones, operated on faster timelines.

Chen’s willingness to wait indefinitely for perfect conditions maximized each engagement’s effectiveness. Third, Chen’s mechanical aptitude enabled technical innovation. He didn’t just use the mirror. He understood optics, angles, reflection principles, and sunpath prediction. This technical knowledge let him maximize mirror effectiveness under varying conditions.

Less technically minded snipers might have tried mirrors but abandoned them after initial difficulties. Fourth, Chen’s psychological insight surpassed conventional military thinking. He recognized that enemy training and discipline typically viewed as pure advantages created predictable response patterns that could be exploited. This counterintuitive insight that strength becomes weakness under correct exploitation.

demonstrated sophisticated understanding of tactical psychology. These factors combined to create exceptional effectiveness. The mirror was tool. Chen’s skills and insights made it weapon. Robert Chen died in 2009 at age 88 in Daily City, California. His obituary mentioned his Marine service and Navy Cross, but focused on his 50-year career in manufacturing and his family’s three children and eight grandchildren.

Local veterans organization conducted military funeral honors. The rifle salute and flag presentation went to his widow. Among Chen’s papers, family found detailed technical drawings of mirror positioning techniques created from memory in 1990s for historical preservation.

These drawings donated to Marine Corps Museum provide most comprehensive documentation of techniques physical implementation. They reveal sophistication that written descriptions couldn’t fully capture. The drawings show mirror holders constructed from wire and tape. angle calculations accounting for sun path and time of day, positioning techniques for different terrain types, and complex multi-mirror setups requiring careful coordination.

The precision and detail demonstrate engineering mindset applied to tactical problems. Also found were personal journals Chen kept sporadically after the war. Entries from 1946 through 1950 described nightmares about Guam, guilt about specific kills he remembered, and struggle to reconcile military necessity with human cost.

Later entries from 1960s showed gradually achieving peace with past, accepting that contradiction between duty and conscience would remain unresolved. One 1978 entry proved particularly revealing. 34 years since Guam. The faces are mostly gone now, but the number remains. 72. I counted then, I count now.

Emma asks why I remember the number. If memories cause pain, I remember because forgetting would be worse. Those 72 men existed. They died by my hand. Forgetting the count would dishonor their existence by pretending their deaths didn’t matter. They did matter. That’s why I remember. This entry captured moral complexity many combat veterans experience.

Remembering causes pain, but forgetting feels like moral failure. The compromise is carrying memory has permanent burden. Modern military ethicists studying Chen’s journals note his refusal to seek absolution or justify actions through necessity. He maintained that killing in war, even justified killing, carries permanent moral weight that shouldn’t be minimized through rationalization.

This perspective, unusual among military personnel who typically emphasize mission necessity, suggests Chen possessed moral sophistication that military culture doesn’t always accommodate. The technical legacy of Chen’s mirror technique extends into surprising modern applications. Military deception units use laser pointers and reflected light to create false signatures that draw enemy attention or confuse targeting systems.

Electronic warfare employs the same principle Chen discovered create stimulus enemy cannot ignore then exploit resulting predictable response. Counter sniper tactics specifically incorporate lessons from Chen’s operation. Modern forces trained to ignore unusual visual phenomena report rather than investigate and assume any unexplained light is potential threat.

These doctrines exist because Chen proved light distraction worked devastatingly well when enemies investigated predictably. The psychological warfare implications influenced development of modern doctrine. Understanding and exploiting enemy cultural and institutional responses became central to US military operations.

Chen demonstrated that enemy strengths, training, discipline, duty consciousness could become vulnerabilities under correct exploitation. This insight shaped approach to asymmetric warfare where understanding enemy psychology matters more than matching enemy firepower. In 2015, Marine Corps published updated sniper manual, including expanded section on historical innovations.

Chen’s photograph appears alongside text stating, “Sergeant Robert Chen demonstrated that effectiveness in combat stems from understanding adversary psychology and exploiting predictable responses. His employment of simple mirrors to create tactical advantage exemplified Marine Corps values of innovation, adaptability, and mission accomplishment through creative application of basic principles.

The broader lessons from Chen’s operation extend beyond military application. His story illustrates that significant advantages can emerge from simple tools used creatively. The mirror cost 35 but achieved results expensive equipment couldn’t match. This principle that understanding and creativity matter more than resources applies across human endeavors.

Second, Chen’s success depended on patient observation preceding action. He spent days watching Japanese forces before implementing mirror technique. This emphasis on observation before intervention rare in military operations that prize speed and aggression proved more effective than immediate action would have been.

Third, cultural diversity provided tactical advantage. Chen’s background navigating between cultures taught skills that purely monocultural individuals might not develop. military organizations that embraced diversity, access, broader range of perspectives and approaches. Chen’s success validated diversity as force multiplier, though 1940s military didn’t frame it that way.

Fourth, moral complexity doesn’t invalidate tactical success. Chen achieved exceptional results while maintaining awareness of human cost. These aren’t contradictory. Effective warriors can recognize necessity while acknowledging tragedy. This moral sophistication, which military culture sometimes views as weakness, actually represents maturity and humanity worth preserving.

In final assessment, Robert Chen’s 3-day mirror technique operation represents convergence of technical skill, psychological insight, tactical creativity, and individual initiative. A Chinese American Marine using 35 cent shaving mirror and Springfield rifle achieved 72 confirmed kills against entrenched Japanese defenders who’d stalled American advance for days.

The technique was simple. Position mirror to reflect sunlight toward enemy positions. Create patterns suggesting American tactical activity. Wait for investigation reflex to expose enemy soldiers. Engage with precision fire. Displace immediately. Repeat. The execution required exceptional skill, patience, and insight.

The results exceeded anything achievable through conventional tactics. But Chen’s legacy isn’t primarily the kills or technique. It’s the demonstration that understanding psychology matters more than matching firepower. That creativity trumps resources. That diversity brings advantage.

that moral awareness coexists with tactical effectiveness. These lessons demonstrated in three days on Guam remain relevant wherever humans face complex challenges. The shaving mirror itself preserved in Chen family’s possession was donated to National Museum of the Marine Corps in 2012, 3 years after Chen’s death.

It sits in a display case alongside his Springfield rifle, Navy Cross, and technical drawings. The placard concludes with Chen’s own words from his final interview before death. The mirror was just tool. Understanding was the weapon. Japanese soldiers couldn’t help investigating unusual lights because humans are curious. I used their humanity against them. That’s warfare’s tragedy.

We weaponize fundamental human traits, then wonder why we carry permanent scars. Those words provide fitting epitap for a marine who achieved extraordinary tactical success while refusing to minimize its human cost. Robert Chen turned simple mirror into 72 confirmed kills. But he also carried those 72 deaths for 65 years. Never seeking absolution, never forgetting the count, never pretending necessity erased tragedy. The farm boy who became sniper.

The Chinese American who served in segregated military. The warrior who acknowledged moral weight. The innovator who proved simplicity beats complexity. All these aspects comprised Robert Chin. His three days with shaving mirror changed tactical doctrine. His 65 years after changed nothing about fundamental truth. Killing in war, even when necessary, carries permanent cost that honor demands we acknowledge.

That’s the complete lesson of the shaving mirror trick. Not just how it worked, but what it cost. Not just tactical triumph, but human burden. The 72 Japanese soldiers died. Robert Chen carried their deaths until his own. Both truths matter. Neither cancels the other. That’s the reality of war that comfortable distance lets us forget. But veterans like Chen remembered every day.