March 4th, 1944, 28,000 ft above Berlin. Captain Don Gentile’s fuel gauge read dangerously low, his P-51 Mustang had escorted B17 bombers from England to the heart of Nazi Germany, 600 m, the deepest penetration into German airspace. American fighters had ever attempted. Every pilot in his squadron was watching their fuel gauges with the same growing dread.

They had enough fuel to reach Berlin. But according to every calculation, every engineering specification, every official Army Air Force manual, they didn’t have enough fuel to make it home. This mission should have been impossible. 6 months earlier, it had been impossible.

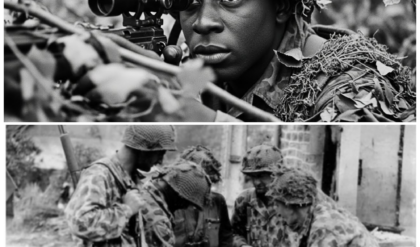

American bombers flying deep into Germany were being slaughtered by Luftvafa fighters. Without escort, without protection, B17s and B-24s fell from German skies at catastrophic rates. Some missions lost over 20% of aircraft. Entire bomber groups were being destroyed. The fighters that could protect them, the P-47s and P-51s, could barely make it to the German border before having to turn back.

Their internal fuel tanks simply couldn’t carry enough fuel for the round trip. The solution to this impossible problem didn’t come from engineers at Wrightfield. It didn’t come from aircraft designers at North American Aviation. It didn’t come from strategic planners at 8th Air Force headquarters.

It came from a motorpool mechanic who looked at a fighter plane and asked a question that everyone else thought was crazy. What if we just strapped more fuel tanks to the outside? The idea seemed absurd, dangerous, against every principle of aerodynamic design. The Army Air Force had officially rejected external fuel tanks as unsafe, impractical, and aerodynamically unsound.

But Captain Gentile was alive above Berlin because one stubborn mechanic refused to accept that rejection because he built the first crude external fuel tank in a maintenance hanger using salvaged parts and sheer determination because he proved that sometimes the craziest ideas are the ones that change history. This is the story of how one mechanic’s garage built invention doubled the range of American fighters and won the air war over Europe. The slaughter begins. October 14, 1943, Schwinfort, Germany.

The mission would become known as Black Thursday. The target was Germany’s ballbearing production facilities. The strategic logic was sound. Destroy the ball bearings, crippled German war production. 291B7. Flying fortresses took off from England that morning. They would fly without fighter escort beyond the German border.

The P-47 Thunderbolts could only accompany them to the edge of Germany before fuel limitations forced them to turn back. What happened next shocked even hardened bomber crews. German fighters freed from the threat of American escorts attacked in waves. They came from above, below, headon. Messers 109s and Faka Wolf 190s concentrated on individual bombers attacking until they fell. The mathematics of destruction were brutal. 60 B7s shot down.

Over 600 American airmen killed or captured. Another 17 bombers so badly damaged they never flew again. The loss rate was 26% unsustainable, catastrophic. If continued, the entire eighth air force bomber fleet would be destroyed within months. Lieutenant Colonel Bernle, flying as an observer on that mission, described the German attacks in his report.

They came in from 12:00 level, firing as they closed. When they passed, more fighters attacked from 6:00 without escort. We were helpless. I watched Beern 17s explode, break apart, spin down trailing fire. I counted 23 parachutes. Over a 100 men didn’t make it out. The Schweinford raid forced a brutal reckoning.

Long- range bomber missions without fighter escort were suicide, but fighters didn’t have the range to protect bombers deep into Germany. The Air Force faced an impossible choice. Stop strategic bombing. essentially conceding the air war to Germany or continue losing bombers at rates that would destroy the force. At 8th Air Force headquarters in High Wom, England, staff officers calculated the numbers.

If loss rates continued at 20 to 25%, they would run out of bombers before Germany ran out of fighters. General Ira Eker, commanding ETH Air Force, sent an urgent cable to Washington. Without long range fighter escort, strategic bombing campaign cannot continue. require immediate solution to fighter range limitation. Current situation untenable.

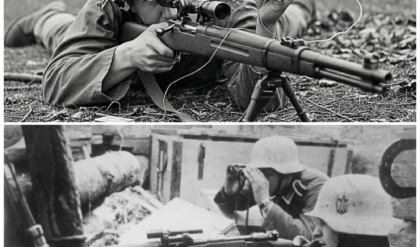

The solution everyone wanted was simple. Build fighters with longer range. But that wasn’t simple at all. The engineering problem. November 1943. Wrightfield, Ohio. The Army Air Force’s best aeronautical engineers gathered to solve the range problem. They faced fundamental physics that couldn’t be ignored. Aircraft range depended on a simple equation. Fuel capacity divided by fuel consumption.

To double range, you needed to either double fuel capacity or have fuel consumption. Fuel consumption was already optimized. The Rolls-Royce Merlin engine in the P-51 Mustang was one of the most efficient engines ever built. You couldn’t make it significantly better. That left fuel capacity. The P-51 had internal tanks holding 269 gall.

At cruise consumption of 65 gall per hour, that gave roughly 4 hours of flight time, enough to reach Western Germany and return to reach Berlin required at least 6 hours. That meant carrying 400 g, an additional 131 gall, weighing over 800 lb. The engineers consensus was clear. Adding that much fuel internally was impossible. The aircraft structure couldn’t support it. The center of gravity would shift dangerously.

The additional weight would reduce performance. unacceptably. External fuel tanks were briefly discussed and immediately dismissed. Colonel Donald Putt, director of research and development, stated the official position. External tanks create excessive drag, reducing speed and maneuverability.

They’re vulnerable to enemy fire. They compromise the aircraft’s structural integrity. They’re simply not practical for combat operations. The meeting concluded with no solution. The engineering consensus was that physics prevented fighters from escorting bombers to Berlin. In England, a motorpool mechanic was about to prove them wrong. The crazy mechanic.

November 22nd, 1943. Bodam Airfield, England. Technical Sergeant Benjamin Kelsey wasn’t supposed to be solving strategic problems. His job was maintaining P-51 Mustangs for the 354th Fighter Group, changing oil, replacing spark plugs, patching bullet holes. But Kelsey had a habit of asking questions that annoyed his superiors.

Why couldn’t fighters carry more fuel? Why did they have to turn back at the German border? Why were bomber crews dying because fighters ran out of gas? The official answer was always the same. It’s an engineering problem. The experts are working on it. Do your job, Sergeant. Kelsey did his job. And then on his own time, he did something else.

In a maintenance hanger, after hours using scrap materials and borrowed tools, Kelsey started building. He wasn’t an engineer. He didn’t have aerodynamics training. He just had an idea that seemed obvious to him. If the plane can’t carry more fuel inside, put it outside. He took a 75gallon auxiliary fuel tank from a damaged P47.

The tank was designed to fit inside the fuselage. Kelsey modified it to attach externally under the wing. The modifications were crude welded metal brackets, repurposed fuel lines, a simple mechanical release that would let the pilot jettison the tank when empty or in combat.

His squadron commander, Major James Howard, discovered Kelsey’s project by accident. What the hell are you doing, Sergeant? Kelsey explained, “If we hang this tank under the wing, the pilot gets an extra 75 gallons. That’s maybe an extra hour and a half of flight time, enough to go deeper into Germany.” Howard’s response was immediate.

That’s the craziest thing I’ve ever heard. You can’t just bolt a fuel tank to a fighter’s wing. Have you considered the aerodynamics, the structural stress? What happens if it ruptures in flight? All valid questions. Kelsey had answers for none of them. He just knew it might work. Howard should have ordered him to stop.

Instead, he said something that would change the war. Let’s test it. The first test. November 28th, 1943. Bodisam airfield. Captain Jack Ilfrey volunteered to fly the test. Actually, volunteered wasn’t quite accurate. Howard had asked who wanted to fly a Mustang with an untested mechanically crude fuel tank bolted to the wing. Every pilot suddenly remembered urgent maintenance tasks except Ilfrey.

He looked at Kelsey’s contraption and shrugged, “If it falls off, I’ll jettison it. If it blows up, well, we die in combat anyway. Let’s see if this thing works.” The ground crew filled the external tank with 75 gall of high octane aviation fuel. The tank hung beneath the port wing looking like an afterthought. Bolted to a precision machine.

Ilfrey’s pre-flight was more thorough than usual. He checked every bolt, every connection, every weld. Then he climbed into the cockpit, started the Merlin engine, and taxied to the runway. The takeoff was normal. The tank stayed attached. So far so good. Ilfrey climbed to 10,000 ft and began testing.

How did the tank affect handling? He tried gentle turns, steep turns, rolls. The Mustang handled differently with the asymmetric load, but remained controllable. How was fuel flow? He switched to the external tank. The engine ran smoothly. The fuel system worked. The critical test was the release mechanism. Ilfrey pulled the emergency jettison handle.

The tank fell away cleanly, tumbling toward the English countryside below. Ilfrey brought the Mustang back to Badon and landed. His report was succinct. It works. The tank stayed on during maneuvers. Fuel fed properly. Released when I pulled the handle. It actually works. Major Howard immediately recognized the implications.

If a 75gallon external tank gave 90 extra minutes of flight time, what about bigger tanks? What about tanks under both wings? He sent an urgent message to 8th Air Force headquarters. Have successfully tested external fuel tank installation on P-51. Results positive. Request authorization for expanded testing and operational deployment. The response from headquarters was swift and negative.

External fuel tank concept previously evaluated and rejected. Modifications to aircraft unauthorized. Seesaw testing immediately. Howard read the message, crumpled it up, and turned to Kelsey. Build more tanks. We’re going to need them. The bureaucratic battle. December 1943. 8th Air Force Headquarters. Hi Wickham.

When General Ira Eker learned that a fighter squadron was conducting unauthorized modifications to aircraft, his first instinct was to order court marshals. Major Howard was summoned to headquarters to explain why he’d ignored direct orders to cease testing. Howard’s defense was simple. With respect, sir, we’re losing bombers because fighters can’t escort them.

This invention solves that problem. Every day we don’t use it. More bomber crews die. Ekker’s chief of staff, Brigadier General Frederick Castle, was less diplomatic. You’re a squadron commander, not an engineer. Wrightfield has the best aeronautical engineers in the world. If external tanks worked, they’d have designed them.

Howard pulled out Ilfrey’s test flight report and detailed specifications for Kelsey’s design. He showed fuel consumption calculations, range extensions, potential operational impact. The staff officers were unmoved. The design hadn’t been tested for structural integrity. It hadn’t been evaluated for aerodynamic efficiency. It hadn’t gone through proper channels.

General Eker listened to the argument, then asked one question. How much range does it add? Howard consulted his notes. A 75gallon tank adds approximately 90 minutes of flight time. That’s enough to escort bombers another 150 mi deeper into Germany. Ekker did quick mental math. Current fighter escort ended at the German border. Add 150 mi.

That would cover bombers to the rurer industrial area, maybe Frankfurt. What about larger tanks? Howard had anticipated the question. If we scale up to 150 galon tanks, we could potentially reach Berlin and return. The room fell silent. Berlin was the target everyone wanted to hit. The heart of Nazi Germany, but it was 600 m from England. Unreachable with current fighter escorts. Ekker made his decision.

Overrule Wrightfield’s objections. Authorize immediate production of external fuel tanks. I want a squadron equipped and operational within 30 days. Castle protested. Sir, Rightfield should properly evaluate the design first. Eker cut him off. Right field has had months to solve this problem. They failed.

A motorpool sergeant solved it in 3 weeks with scrap metal. Get these tanks into production now. If you’re fascinated by stories of innovation that changed World War II, make sure to subscribe to our channel. We bring you the untold stories of the mechanics, engineers, and ordinary people who made extraordinary contributions to victory.

Hit that subscribe button so you don’t miss what happens when this crazy idea goes into combat. The rush to production. January 1944. North American Aviation, Englewood, California. When North American Aviation received emergency orders to manufacture external fuel tanks for the P-51, their engineering team was skeptical.

Chief designer Edgar Schmood examined Kelsey’s crude prototype that had been shipped from England. This is your design. Welded scrap metal and improvised brackets. The Army Air Force liaison, Colonel Mark Bradley, was blunt. This is what works. Your job is to make it manufacturable at scale. Schmood’s team spent 72 hours reverse engineering Kelsey’s design.

They refined the aerodynamics, strengthened the attachment points, and streamlined production methods. The final design used pressed aluminum construction, streamlined teardrop shape, standardized mounting brackets, mechanical release mechanism proven in testing. Available in 75gal, 108gal, and 150gal versions. Production began immediately, three shifts, 7 days per week. The first production tanks rolled off the assembly line January 15th.

By months end, North American was producing 200 tanks daily. Simultaneously, modification kits were manufactured to retrofit existing P-51s with external tank mounting points. Every Mustang in England would be modified, but production was only half the battle. The tanks had to be filled, transported, and attached to fighters. The logistics proved challenging.

External tanks were shipped to England by cargo vessel and bomber bases. They were stored in dedicated facilities. Each fighter mission required ground crews to attach tanks, fill them with fuel, and ensure proper connection to the aircraft fuel system. The process added 30 minutes to pre-flight preparation, but those 30 minutes bought 3 hours of flight time.

The first combat mission, January 21st, 1944, Debbdon Airfield, England. The 354th Fighter Group was selected for the first operational mission using external fuel tanks. The target was Frankfurt, 280 mi from England. Beyond the previous maximum fighter escort range, 48 P-51s, each carrying 108 external tanks, prepared for takeoff, the pilots had mixed feelings about the new equipment.

Captain Dwayne Bon voiced what many thought. We’re going into combat with giant bombs strapped to our wings. If a German fighter hits these tanks, we’re flying gasoline bombs. The briefing officer addressed the concern. The tanks are self-sealing, just like your internal tanks. If hit, they’ll leak, but won’t explode, and you can jettison them any time.

The mission briefing was straightforward. Escort the bombers to Frankfurt. Engage any German fighters. Return to base. What wasn’t said, but everyone understood. If the external tanks failed, if they didn’t provide the promised range, fighters would run out of fuel over Germany.

The pilots would have a choice between bailing out over enemy territory or attempting to crash land. This mission was either going to validate Sergeant Kelsey’s crazy idea or prove the right field engineers had been right to reject it. The formation took off at 0830 hours. 48 Mustangs, each with over 400 gallons of fuel, enough theoretically to fly to Frankfurt and back.

As they crossed the English Channel, several pilots reported handling differences with the external tanks. The Mustang was slightly less maneuverable, slightly slower, but it was manageable. They rendevoused with the bomber stream over Belgium. The 17 flying fortresses flying in tight formation heading toward Frankfurt. At the German border, where fighters normally turned back, the P-51s kept going.

For the first time, American fighters penetrated deep into German airspace. The Luftvafa’s response revealed they hadn’t anticipated this development. German fighter controllers monitoring the inbound bomber stream had positioned their fighters beyond the expected range of American escorts. When P-51s appeared over Frankfurt, German pilots were caught completely offguard.

The combat was brief but decisive. The 354th Fighter Group claimed 11 German fighters destroyed with no American losses, but the real victory was psychological. For the first time, American fighters had escorted bombers to a major German industrial target and returned. The external tanks worked. Captain Bon landed at Debton with fuel to spare. His post-m mission report was enthusiastic.

The tanks performed flawlessly. We jettisoned them before engaging German fighters. The Mustang handled normally after release. This changes everything. He was right. It changed everything. The strategic shift. February 1944, 8th Air Force Headquarters. The success of the Frankfurt mission triggered an immediate operational shift.

General James Doolittle, who had replaced Ekker as 8th Air Force Commander, ordered aggressive expansion of external tank use. Every fighter group would be equipped. Every mission would use them. The strategic goal was clear. Destroy the Luftvafa by forcing them to fight under conditions where American fighters had the advantage.

External tanks enabled a revolutionary tactic. Fighters would escort bombers to the target, then break off to attack German airfields. They had enough fuel to hunt, engage, and still return to England. German fighter pilots accustomed to attacking bombers without fighter interference suddenly found themselves fighting for survival.

The first major test came during big week February 20th to 25th 1944. The eighth air force launched massive raids against German aircraft production facilities. The numbers were staggering. 3,800 bomber sorties, 3,700 fighter sorties. Nearly all fighters equipped with external tanks. The Luftvafa rose to defend, but American fighters with extended range were everywhere.

over targets, over German airfields, along flight paths. In one week, German fighter losses exceeded 250 aircraft. More critically, the Luftvafa lost experienced pilots it couldn’t replace. Major Johannes Steinhoff, a German ace with over 100 victories, described the shock in his post-war memoir, “We expected American fighters to turn back at the border as always. Instead, they stayed with the bombers all the way to the target. Then they came after us.

They had the fuel to hunt us. We were no longer hunters. We had become the hunted. The external fuel tanks had fundamentally changed the air wars dynamics. German fighters could no longer attack bombers with impunity. American fighters could now engage anywhere over Germany, Berlin, or bust. March 4th, 1944. Debbden airfield.

The mission everyone had been waiting for. The target Berlin, 630 mi from England. The deepest fighter escort mission ever attempted. 64 P-51s from the 354th and 357th fighter groups would escort bombers to the German capital. Each Mustang carried two external tanks, 150 gallons under each wing.

This gave each fighter a total of 570 gall, enough barely for the round trip. Captain Don Gentile, already an ace with 10 victories, was selected as flight leader. He understood the mission’s significance. If we can escort bombers to Berlin and back, no target in Germany is safe. We win the air war. The pre-mission briefing emphasized fuel management. Every gallon mattered.

Pilots were instructed to maintain precise cruise speed, optimal altitude, and minimal combat maneuvering. The briefing officer was blunt. If you get into an extended dog fight, you won’t have fuel to reach England. Choose your battles carefully. The mission launched at 0800 hours. The weather was poor but flyable.

As they crossed the Dutch coast, several pilots reported nervousness about fuel consumption. Captain Gentile monitored his gauges obsessively. The Merlin engine was consuming fuel exactly as calculated. The external tanks were feeding properly. Everything was working over northern Germany. They rendevoused with the bomber stream.

328 B17 flying fortresses heading to Berlin. The German reaction was fierce. Luftvafa fighters concentrated to defend the capital attacked in waves. Messormid 109s, Faka Wolf 190s, even new jetpowered Messersmidt 262s. The American fighters jettisoned their external tanks and engaged. The dog fight over Berlin involved hundreds of aircraft in a three-dimensional battle across 50 mi of sky.

Captain Gentile shot down two Messers, bringing his total to 12 victories, but he was acutely aware of his fuel gauge. Every minute of combat burned precious fuel. After 15 minutes, he ordered his squadron to disengage. We’ve escorted the bombers in. Time to go home. The flight back was tense. Every pilot monitored fuel consumption.

The calculations that looked good on paper were being tested in reality. They crossed the Dutch coast with fuel gauges reading dangerously low. They crossed the English Channel with warning lights illuminating. Captain Gentile landed at Debdon with less than 15 gallons remaining, barely enough for five more minutes of flight. But he made it. They all made it.

Every fighter that started the mission returned to England. The mission to Berlin proved beyond doubt that external fuel tanks had revolutionized air warfare. No target in Germany was beyond American fighter escort. The Luftvafa’s war diary from March 4th recorded the psychological impact. Enemy fighters appeared in strength over Berlin.

This development indicates American fighters can now escort bombers anywhere over Reich territory. Previous tactical advantages negated. This incredible innovation changed the course of the air war. If you want to see more stories about the unsung heroes and breakthrough inventions that won World War II, subscribe to our channel now.

We’ve got fascinating content coming that you won’t want to miss. Click that subscribe button. The German reaction. March 1944. Luftvafa High Command Berlin. Reich’s Marshall Herman Guring was shown intelligence reports on American external fuel tanks. His response was dismissive. This is temporary. These tanks are vulnerable, inefficient.

Our pilots will shoot them off their wings. General Adolf Galland, commander of German fighter forces, disagreed. The tanks work. American fighters now have unlimited range over Germany. They drop the tanks before engaging, so they don’t affect combat performance. We must adapt our tactics. But adaptation was difficult.

The Luftvafa’s entire defensive strategy had been built on the assumption that American fighters had limited range. German fighters were positioned to intercept bombers after American escorts turned back. Now, American escorts didn’t turn back. German pilots attempted various counter measures.

Some tried to attack American fighters before they could drop their external tanks, but the Americans jettisoned tanks at the first sign of threat. Others attempted to avoid combat when American fighters appeared, preserving their strength to attack unescorted bombers. But there were no longer any unescorted bombers. The psychological impact was profound.

German fighter pilots who had dominated European skies for 4 years found themselves outranged, outnumbered, and outfought. Litines, a luftvafa ace, wrote in his diary, “The Americans can go anywhere now. We take off to intercept, burn fuel, reaching altitude, engage briefly, then must land to refuel. The Americans stay up for hours.

They have fuel to pursue us, to attack our airfields, to hunt us relentlessly. This is not sustainable. The kill ratios reflected the new reality. In March 1944 alone, the Eighth Air Force claimed over 500 German fighters destroyed for fewer than 100 American fighters lost. The production explosion.

April 1944, United States with external fuel tanks proven in combat. Production ramped up dramatically. Multiple manufacturers were contracted. North American Aviation’s Englewood plant produced tanks for P-51s. Republic Aviation manufactured tanks for P47s. Lockheed built tanks for P38s. By April, combined production exceeded 3,000 external tanks daily, enough to equip every fighter mission with fresh tanks. The design continued evolving. Early tanks were relatively crude.

Later versions featured improved aerodynamics, better release mechanisms, and standardized attachment points. The 150gal paper tank became standard called paper because it was manufactured from compressed paper with a plastic coating. Lighter than metal, cheaper to produce, disposable after a single use.

These paper tanks cost $18 each to manufacture. Compared to losing a fighter worth $50,000, they were essentially free. Technical Sergeant Benjamin Kelsey, whose crude prototype had started everything, received a promotion to master sergeant and a commenation. His citation read, “For innovative thinking and technical excellence in developing external fuel tank system for fighter aircraft, significantly contributing to Allied air superiority over Europe. But Kelsey remained at his motorpool job, maintaining fighters. When asked by a

reporter about his invention, he shrugged. I just wanted our guys to have enough fuel to do their job. Didn’t think it was that big a deal. That not big deal had revolutionized air warfare. The final tally. May 1944 to May 1945. The statistics tell the story of external fuel tanks impact.

Between May 1944 and wars end, American fighters flew 137,000 long range escort missions. Nearly all used external fuel tanks, German aircraft production facilities were systematically destroyed. Oil refineries were obliterated. Transportation networks were shattered. All because bombers could reach any target in Germany with fighter protection. Luftvafa losses were catastrophic.

In the final year of war, Germany lost over 18,000 aircraft, most to American fighters equipped with external fuel tanks. The kill ratio favored Americans by 6:1 for every American fighter lost. Six German aircraft were destroyed. German pilot quality collapsed. Experienced aces were killed faster than replacements could be trained. By late 1944, average German pilot training had dropped from 250 hours to 60 hours.

American pilots protected by long range escorts gained experience and confidence. Aces like Francis Gabreski, Robert Johnson, and George Prey achieved victory totals that would have been impossible without extended range. The bomber offensive, which had nearly been cancelled after Black Thursday, continued with devastating effectiveness.

In the final year of war, the Eighth Air Force dropped over 400,000 tons of bombs on German targets. Without external fuel tanks, none of this would have been possible. The human cost. Behind statistics are human stories. Bomber crews who survived missions because fighters protected them all the way to targets and back.

Staff Sergeant Joseph Connelly, a B17 waste gunner, flew 35 missions. He later wrote, “For my first 10 missions, we were on our own after crossing into Germany. German fighters attacked us constantly. We lost multiple aircraft every mission. For my last 25 missions, we had fighter escort the entire way. We still encountered Germans, but our fighters drove them off.

I probably wouldn’t have survived 35 missions without those escorts. The mathematics support his assessment. Before long range escorts, bomber loss rates averaged 8 to 10% per mission. After long range escorts became standard, loss rates dropped to 2 to 3%. This meant for every 100 bombers on a mission, 6 to eight more aircraft returned home.

Each aircraft carried 10 crewmen. 60 to 80 lives saved per 100 bombers. over thousands of missions. This translated to tens of thousands of American lives saved. Luftwaffa pilots paid the price. Experienced German aces, men with hundreds of victories, fell to American fighters over their own territory.

Major Egon Meyer, credited with developing the head-on attack against B17s, shot down 102 Allied aircraft. He was killed by P47 fighters over Germany in March 1944. Hedman Hans Phillip with 206 victories fell to P-51s in October 1943 just after external tanks entered service.

The list of German aces killed by American fighters equipped with external tanks is extensive. The Luftvafa’s experience and expertise was systematically destroyed. The strategic impact. Post-war analysis by both American and German military historians consistently identifies external fuel tanks as one of the war’s most decisive innovations.

General Carl Spots, commanding US strategic air forces in Europe, stated, “The external fuel tank was as important to winning the air war as any weapon system we deployed. It transformed tactical realities and enabled strategic success.” Albert Spear, Nazi armament’s minister, wrote in his memoir, “The American success in extending fighter range was catastrophic for Germany.

Once their fighters could escort bombers anywhere, our defensive strategy collapsed. We could not protect our industry, our cities, or our military.” This single innovation arguably shortened the war by months. Reich’s Marshall Goring during postwar interrogation admitted, “I knew we had lost the air war when American fighters appeared over Berlin.

Until then, I believed distance protected us. The external fuel tanks eliminated that protection. The technologies implications extended beyond World War II. Modern aerial refueling, which allows military aircraft to operate globally, descends directly from the external tank concept.

Extending aircraft range through additional fuel capacity, whether carried externally or transferred in flight, remains fundamental to air power projection. The legacy of innovation. The external fuel tank story exemplifies innovation under pressure. When orthodox approaches failed, an unconventional solution from an unexpected source succeeded.

Technical sergeant Benjamin Kelsey wasn’t supposed to solve strategic problems. He was a mechanic, but he saw a problem, imagined a solution, and built a prototype. Major James Howard wasn’t supposed to authorize unauthorized aircraft modifications, but he recognized a good idea and supported it despite regulations. General Ira Eker wasn’t supposed to override his engineering staff’s objections, but he understood that perfect can be the enemy of good enough and that good enough now beats perfect later. The external fuel tank succeeded because people at

multiple levels were willing to break rules, challenge assumptions, and take risks. This pattern repeats throughout military history. Innovation often comes from unexpected sources. Solutions frequently violate conventional wisdom. Success requires leadership willing to support unconventional ideas, the mechanics reward.

Master Sergeant Benjamin Kelsey remained in the Army Air Force through the war’s end. He received several more commendations for technical innovations, though none as significant as external fuel tanks. After the war, he was offered engineering positions with major aircraft manufacturers. He declined them all. He remained a mechanic because he enjoyed the work.

In 1953, The Air Force magazine ran a feature story on wartime innovations. They interviewed Kelsey about his external fuel tank invention. The reporter asked what motivated him to develop the design. Kelsey’s answer was characteristically straightforward. Bomber crews were dying. Fighters couldn’t protect them because of fuel range. Seemed like putting more fuel on the plane would solve the problem.

So, I did, the reporter pressed. But you must have known the army had rejected external tanks as impractical. What made you think you could succeed? Where official engineers failed? Kelsey smiled. I didn’t know what was impossible because nobody told me it was impossible. If they had, I probably wouldn’t have tried.

Sometimes not knowing something can’t be done is the best way to do it. That quote captures the essence of innovation. Sometimes the people least constrained by conventional wisdom are the ones who solve seemingly impossible problems. Kelsey died in 1987 at age 74.

His obituary mentioned his World War II service, but barely referenced the external fuel tank invention. He remained relatively unknown outside aviation history circles. But every modern military aircraft that uses external tanks, every fighter that can be aerial refueled, every long range mission flown by any air force in the world owes something to a motorpool mechanic who looked at a fighter plane and asked, “What if we just strap more fuel to the outside?” The final mission.

May 7, 1945, one day before German surrender, Captain Don Gentile, now credited with 30 victories, flew his final combat mission. The target was Prague, Czechoslovakia. The mission profile was routine. Escort bombers to target. Engage enemy fighters if present. Return to base. His P-51 carried two 150galon external tanks. Standard equipment. Routine procedure. Nobody even commented on them anymore.

But Gentile remembered his first mission to Berlin. The fear that fuel would run out, the constant monitoring of gauges, the relief of landing with fuel to spare. External tanks had transformed that terror into routine confidence. American fighters could go anywhere, stay as long as needed, fight when necessary, and always have fuel to return home.

As he flew over Czechoslovakia, Gentile thought about all the innovations that had won the air war. Improved aircraft, better tactics, superior training. But underneath it all, enabling everything else were those simple aluminum tanks hanging under his wings. Conceived by a mechanic in a maintenance hanger built from scrap metal.

Rejected by official engineers as impractical, those impractical tanks had changed history. Gentile landed at Debton for the last time as the war ended. He’d survived 58 combat missions, shot down 30 enemy aircraft, and never been forced down by lack of fuel. The external tanks hanging under his Mustang’s wings had been as responsible for his survival as his skill, his training, or his courage.

The lesson endures. The story of external fuel tanks teaches lessons that transcend military history. Innovation often comes from unexpected sources. The best ideas don’t always originate in research laboratories or corporate headquarters. Sometimes they come from people doing practical work, seeing problems directly, and imagining simple solutions. Bureaucracy can impede progress.

The Army Air Force engineering establishment had rejected external tanks based on theoretical objections. They were wrong. A mechanic with no aerodynamics training was right. Leadership matters. General Eker could have court marshaled Major Howard for unauthorized testing. Instead, he overruled his staff and authorized production. That decision saved thousands of lives.

Perfect is the enemy of good enough. Kelsey’s first prototype was crude, but it worked. Waiting for right field to develop a theoretically perfect design would have cost months and lives. Sometimes the simplest solutions are the best. The external fuel tank wasn’t high technology. It was a tank strapped to a wing. But it solved a problem that had styied experts.

These lessons remain relevant. In any field where innovation matters, the organizations that succeed are those that listen to unconventional voices, support crazy ideas and implement good enough solutions quickly rather than waiting for perfect solutions. Later, the final word. March 4th, 1944. Above Berlin, Captain Don Gentile completed his mission and turned toward England.

His fuel gauges showed enough fuel to make it home. Barely, but enough. Below him, German fighters burned. Behind him, American bombers completed their bomb runs without fighter interference. Around him, 63 other P-51s prepared for the long flight home. All because one mechanic refused to accept that the impossible was impossible.

The external fuel tanks hanging under Gentile’s wings weren’t elegant. They weren’t sophisticated. They were crude aluminum cans with improvised mounting brackets. But they worked. And in war, working is all that matters. Technical Sergeant Benjamin Kelce’s crazy idea had doubled bomber range, destroyed the Luftwaffa, and won the air war over Europe.

Sometimes the craziest ideas are the ones that change the world. The mechanic who built the first external fuel tank in a maintenance hanger using scrap metal proved that innovation doesn’t require credentials, authority, or official approval. It requires vision to see solutions others miss.

Courage to build despite objections, determination to prove that crazy ideas can work. That lesson echoes through history. The next breakthrough, the next innovation that changes everything might not come from expected sources or follow conventional paths. It might come from a mechanic in a motorpool who looks at an impossible problem and asks, “What if we just try this crazy idea?” And sometimes that crazy idea changes