October 6th, 1973. 1,400 hours deep beneath the surface. The Syrian general staff was orchestrating an apocalypse. To the Soviet advisers standing quietly in the corners of the room, this was not just a regional conflict. This was the ultimate field test. For years, the Soviet Union had poured billions of rubles, their most advanced armor, and their rigid tactical doctrine into the Syrian Arab army. They had built a machine designed to crush Western resistance through pure mathematical inevitability. On the

situation map, the logic was flawless. To the north on the Golan Heights, the equation was simple. 1,400 Syrian tanks were revving their engines. Facing them, scattered across the rocky volcanic plateau were fewer than 180 Israeli tanks. The ratio was nearly 10:1. In specific breakthrough sectors, it was closer to 15 to1.

A Soviet senior military adviser, let us call him Colonel Vulov, watched the markers move on the map. He checked his watch. The sun was setting. It was Yum Kipur, the holiest day of the Jewish calendar. The Israeli reserveists were at home fasting. Their radios were silent. Their guard was down. According to the Soviet wargaming models run in Moscow, the Syrian armored columns should sweep across the Golan and reach the Jordan River within 24 hours. There was no variable in the equation that allowed for defeat.

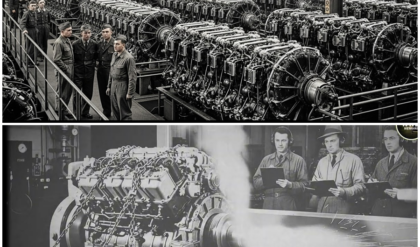

The sheer mass of Soviet steel was a physical law that could not be broken. The offensive began with an artillery barrage that turned the horizon into a wall of fire. Then the steel tsunami rolled forward. Three massive infantry divisions spearheaded by hundreds of T-55 tanks and the brand new terrifying T-62 tanks crossed the Purple Line. For the first 6 hours, the mood in the Damascus bunker was professional, bordering on jubilant.

The reports flowed in. The Israeli minefields were breached. The anti-tank ditches were breached. The sheer weight of the offensive was crushing the thin line of defenders. Vulov nodded approvingly. The T62 tank with its 115 mm smooth boore gun was superior to anything the Israelis possessed on paper.

It had better armor and crucially, it had modern active infrared night vision systems. The Israelis did not. As night fell over the Golan, the Syrian advantage should have become absolute. The Soviet advisers expected the Israeli defense to collapse into chaos under the cover of darkness.

But as midnight approached on October 6th, the rhythm of the teleprinters changed. The reports coming from the seventh infantry division in the northern sector were inconsistent. They were not reporting a breakthrough. They were reporting heavy resistance. Vulov frowned.

Resistance? from whom intelligence stated there was barely a battalion of tanks facing them in that sector. The mathematics said those Israeli tanks should have been overwhelmed, flanked, and destroyed by volume of fire hours ago. Then a frantic voice transmission crackled over the radio network, intercepted and relayed to the command center. It was a Syrian battalion commander from the lead echelon. He was screaming.

He claimed he was taking fire from Phantom Tanks. He reported that his lead company of 10 tanks had been liquidated in less than 2 minutes. “Liquidated?” A Syrian general asked, grabbing the handset. “By air support? Is the Israeli air force active?” “No air support?” the voice crackled back, panic rising in the pitch. “Direct fire, long range. We cannot see them. They are shooting us from the darkness.

They are hitting us from 3,000 m.” The bunker fell silent. Vulov exchanged a worried glance with his colleagues. This was technically impossible. The battle was taking place in pitch blackness. The Israelis were operating older western tanks, modified centurions and patterns.

These machines did not possess the technology to engage targets effectively at 3,000 m in daylight, let alone at night without infrared search lights. And yet, the reports kept coming. One T-55 tank destroyed, then another, then an entire platoon of T62 tanks burning. By dawn on October 7th, the confusion had curdled into a cold dread. The map did not look right.

The red markers representing the Syrian offensive were not sweeping down to the Sea of Galilee. They were bunching up, stalling in a narrow corridor that would soon be known as the Valley of Tears. The Soviet advisers began pulling technical schematics. They scrutinized the data on the Israeli order of battle. They looked for the presence of secret weapons.

Had the Americans shipped a new guided missile system overnight? Were there NATO mercenaries in the turrets? The numbers were horrifying. In one sector, a single platoon of four Israeli tanks was holding back an entire Syrian brigade. The Syrians would crest a ridge, expecting to find the enemy rooted, only to be met with devastatingly accurate fire that targeted the weak points of their armor, the turret rings, the fuel cells. The precision was surgical. It was mechanical murder. The confusion in the bunker deepened when reconnaissance

photos arrived later that morning. They showed the battlefield. It was a graveyard. Dozens, then scores, then hundreds of Soviet supplied tanks lay smoking on the bassalt rocks. Their turrets were blown off. Their hulls were blackened. Vulov stared at the grainy images. He saw the wreckage of the Soviet Union’s best export technology.

The T62 tank was designed to be the apex predator of the battlefield. It was lowprofile, heavily armored, and packed a punch that could penetrate any NATO tank. Yet here in the Golan, they were being slaughtered by tall, boxy, clumsy looking tanks that looked like relics from the 1950s.

“It defies logic,” one of the junior analysts muttered, tracing the line of destroyed vehicles. “The Israelis are outnumbered 14 to1. Their tanks are slower. They have smaller guns. They have no night vision. How are they stopping the advance?” This is the question that haunts military historians and haunted the Kremlin in 1973.

How does a force that should be mathematically extinct stop an unstoppable object? The answer lay not just in the metal but in a secret adaptation, a ghost in the machine that the Soviets had completely overlooked. Before we dive into the mystery of the Valley of Tears and the investigation that followed, if you want to understand the hidden mechanics of global conflict and the untold stories of military history, make sure you subscribe to Cold War Impact. We decode the declassified files to show you how the world really works. Back in Damascus, the situation

was spiraling. The Syrian commanders were accusing their tank crews of cowardice. The tank crews were accusing their commanders of sending them into a trap. But the Soviet advisers knew better. They knew the Syrian crews were brave. They were dying in their hundreds, pressing the attack. The problem was something else.

By the afternoon of October 7th, a new report arrived from the front. A Syrian recovery vehicle had managed to drag a disabled Israeli tank back to their lines before being forced to retreat. It was a Centurion, but it looked wrong. The barrel was different. The engine deck was modified.

It was covered in strange reactive plates and stowage boxes. Volkov ordered the technical team to the front immediately. They needed to see this machine. They needed to understand what was killing their T62 tanks before the entire offensive collapsed. They had to know if this was a new American super weapon or something else entirely.

As they prepared to leave Damascus for the front lines, the artillery thunder in the distance grew louder. The Israelis weren’t just holding. They were starting to push back. The Soviet doctrine relied on mass. It relied on the idea that quantity has a quality all its own. But in the volcanic dust of the Golan Heights, that quality was failing.

The advisers were about to step into a crime scene where the victim was their own ideology and the killer was a mystery wrapped in British steel and American engineering. October 8th, 1973. The northern sector. Colonel Vulov stood at the edge of the plateau. The wind whipping dust and the acrid smell of diesel fuel into his face. He was no longer in the comfortable obstraction of the Damascus bunker.

He was a few kilometers from the front line at a chaotic staging area where the remnants of the Syrian 7th Infantry Division were trying to regroup. What he saw defied the laws of military science. The Syrian army was equipped with the T-55 and T62 tanks. These were lowslung aggressive machines designed to present the smallest possible target to the enemy.

They were the embodiment of the Soviet philosophy. hard to hit, harder to kill. In contrast, the British-made Centurion, the tank the Israelis were using, was a dinosaur. It was tall, boxy, and flat-sided. It should have been a magnet for armor-piercing rounds. Vulov grabbed a terrified Syrian tank commander, a lieutenant who had just walked back from the front line on foot, his face black with soot. “Tell me what you saw,” Vulov demanded through a translator. “How are they hitting you? You have the night

vision. You have the numbers.” The lieutenant’s eyes were wide, staring at something Vulov couldn’t see. We don’t see them until we burn, he whispered. We turn on the infrared search lights to find a target. We scan the darkness. We see nothing, but the moment we turn on the light, a shell hits us. It is as if the light attracts the bullet.

Vulov cursed. The T62 tanks utilized active infrared. To see in the dark, they had to project a beam of infrared light, invisible to the naked eye, but visible to anyone with a viewing device. But the Israelis didn’t have infrared viewers. Intelligence was certain of this.

So, how were the Israelis targeting a T62 tank the instant it turned on its spotlight? It was as if the Israelis could see the invisible beam. The mystery deepened when Vulov examined the damage on a T-55 tank that had been towed back to the rear. The entry hole was small, clean, and terrifyingly precise. It wasn’t a random hit. The shell had pierced the turret ring. The chaotic moving joint between the body and the gun.

“He was moving,” the mechanic explained, gesturing to the ruined tank. “This tank was moving at 30 kmh over rocks, and he was hit in the turret ring. To make that shot, the Israeli gunner would have to calculate the lead, the drop, and the bounce of his own tank perfectly in a split second.” Volkov ran his hand over the cold steel.

The Soviet doctrine relied on the stop to fire method. To shoot accurately, a T-55 tank usually had to halt. This made them vulnerable. But the reports claimed the Israelis were firing while maneuvering or firing from positions that seemed geometrically impossible. The terrain of the Golan is not a flat plane.

It is a nightmare of volcanic ridges, sudden drops, and basalt boulders. It is tank killing country. The Soviet advisers had warned the Syrians that this terrain favored the defender, but they had calculated that the T62 tank’s superior powertoweight ratio would allow them to swarm the obstacles. Instead, the terrain had become a weapon. Reports were coming in of pop-up attacks.

A Syrian column would be advancing through a wadi, a dry riverbed. Suddenly, the turret of an Israeli tank would appear over the crest of a ridge, fire a shot that destroyed the lead tank, and then vanish backward before the Syrians could return fire. “It is like fighting ghosts,” the Syrian general complained, slamming his fist on the hood of a jeep.

“Our guns cannot elevate enough to hit them on the high ridges, and they cannot depress enough to hit them when we are above them. They are dancing around us.” Vulov looked at the map again, “The Valley of Tears. That’s what the soldiers were calling the breakthrough sector.

Now, in a space of just a few kilometers, hundreds of Syrian tanks were burning. The smoke was so thick it was creating an artificial twilight. But the most baffling piece of intelligence came from a radio interception recorded an hour prior. An Israeli company commander code named Zvika was heard coordinating his unit. The Soviet analysts listened to the tape confused.

He is ordering tanks to move to position ALF, then position Bet. the analyst said. But Colonel, listen to the background noise. We hear only one engine. We hear only one gun firing. Vulov listened. The analyst was right. It sounded like a single tank rushing back and forth, firing like a maniac, pretending to be a platoon. One tank? Vulkov asked incredulous. You are telling me one tank is holding up a brigade? It seems so.

Or he is moving so fast our crews think they are surrounded. The Soviet military worldview was crumbling. They believed in the collective, the battalion, the regiment. The idea that individual crew skill or a specific mechanical quirk could override mass formations was heresy. Yet, the evidence was piling up in the burning wrecks of the T62 tanks.

There was something about the Israeli tank itself that they were missing. Vulkoff remembered the dossier on the Centurion. It was developed in 1945. It was underpowered. Its range was short. By 1973, it should have been obsolete. Why was it moving with such agility in the volcanic rock? Why was it not overheating? Why was its rate of fire nearly double that of the T62 tank? A disturbing thought entered Vulkov’s mind.

The T62 tank used a massive 115 mm round. The brass casing was heavy. The interior of the tank was cramped, terribly cramped. To load the gun, the loader had to wrestle the shell into the brereech while the gun automatically ejected the spent casing. It was a violent, dangerous dance inside a steel box. After a few hours of combat, the Syrian loaders were exhausted.

Their rate of fire dropped to two or three rounds per minute. The Israelis were reportedly firing six, maybe eight rounds per minute, and they had been fighting for 48 hours straight. “We need to see inside one of their tanks,” Vulov said, his voice low. not a burnt-out hull. I need a functioning machine. I need to see the engine. I need to see the gun sights.

As evening fell on October 8th, the tide began to turn, but not in the way the Soviets expected. The Syrians were running out of morale before they ran out of tanks. The Valley of Tears was choked with the dead, and still the thin line of old boxy tanks on the ridge held firm. Volov looked through his binoculars at the distant muzzle flashes on the horizon.

He realized he wasn’t watching a battle of numbers. He was watching a collision of philosophies. And the Soviet philosophy was bleeding to death. The mystery was no longer about if the offensive would fail. It was about what exactly was inside those Israeli tanks that turned them into rapid fire snipers.

Was it a computer? A new American auto loader? The answer would arrive the next morning in the form of a captured Shot Cal tank towed away from the battlefield by a desperate Syrian recovery team. When Vulov finally climbed inside the enemy turret, what he found would shock him, not because of its complexity, but because of its simplicity.

October 9th, 1973. The crisis point. The battle for the Valley of Tears had raged for three days and three nights. The sheer volume of fire had ground the basalt rocks into fine gray powder. Colonel Vulov was now stationed at a forward observation post, looking through a high-powered periscope.

Beside him, the Syrian division commander was pale, his hands shaking as he held a radio handset. The mathematics of war had finally caught up with the Israelis. Of the roughly 100 tanks that had started the defense of this sector, barely 20 remained operational.

The Syrian 7th Infantry Division, reinforced by the Republican Guard T62 tanks, was preparing for the final hammer blow. They had pushed the battered Israeli defenders to the very edge of the escarment. There was nowhere left for the Zionists to retreat. Behind them was a steep drop into the Sea of Galilee. “This is it,” the Syrian commander muttered. “They are out of ammunition. They are out of fuel. We will wash them into the lake.

” Vulov watched the T62 tanks rumble forward. It was a magnificent sight, a wave of armor advancing up the slope. But as he watched, he noticed something peculiar, a geometric anomaly that made his stomach turn. The Syrian tanks were attacking uphill.

To engage the Israeli tanks dug in on the ridge, the T62 gunners had to elevate their massive 115 mm guns. But as they crested the steep lava ridges, they encountered a fatal flaw in Soviet design engineering, one that had never appeared on the flat testing grounds of Russia or the deserts of Egypt. To keep the T62 tank low and difficult to hit, Soviet engineers had flattened the turret. This meant there was very little room inside for the breach of the gun to move up and down.

Consequently, the T62 tank had a terrible gun depression. It could barely aim downward. Vulov watched in horror as a company of T62 tanks crested a ridge. They were now face tof face with the surviving Israeli centurions hidden in the rocks below them. The Syrian gunners frantically tried to crank their guns down to shoot the enemy, but the barrels hit the mechanical stops.

They were pointing uselessly over the heads of the Israeli tanks. The Syrian tanks were exposed, silhouetted against the sky, unable to bring their weapons to bear. Conversely, the obsolete Israeli tanks displayed a terrifying flexibility. Their tall, boxy turrets allowed their guns to tilt far downward 10° of depression compared to the meager four or 5° of the Soviet tanks.

The Israelis could hide their entire hull behind a rock, tip their gun barrel over the edge, and fire into the exposed bellies of the Syrian tanks as they crested the hill. “They are shooting us from the ground up,” the Syrian commander screamed. It was a massacre of geometry. The superior Soviet tank was blind to what was right in front of it. But even with this tactical advantage, the sheer numbers were overwhelming.

The Israelis were down to six or seven tanks in the central sector. The Syrian force still numbered in the hundreds. Then the twist occurred the moment that is studied in every war college from West Point to Moscow. Just as the Syrian forces were about to overrun the final ridge, a victory that was minutes away, the Israeli commander, Lieutenant Colonel Avagdor Kahalani did the unthinkable.

Instead of retreating or digging in for a final stand, he ordered his handful of surviving tanks to charge. “Charge?” Vulov whispered, watching the dust clouds. “He is attacking a division with a platoon. It was a bluff of historic proportions. The surviving Israeli tanks surged forward, firing their machine guns and cannons frantically.

To the exhausted, terrified Syrian crews who had seen hundreds of their comrades burn over the last 3 days. This didn’t look like a desperate last stand. It looked like a fresh counterattack. The Syrian nerve broke. Convinced that fresh Israeli reserves had arrived, which they had not, and unable to effectively target the hullown tanks due to the elevation issues, the Syrian lead elements began to reverse.

The reverse turned into a retreat. The retreat turned into a route. Volkov slammed his fist against the bunker wall. Stop them. They have nothing left. You are winning. But it was too late. The wall of steel was receding. 1,400 tanks had been stopped by a force that by all rights should have been dead 2 days ago.

Later that afternoon, the battlefield fell into an eerie silence. The Valley of Tears was a smoking ruin. The immediate threat was over, but for Vulov and the Soviet technical team, the real work was just beginning. They had to understand the machine that had beaten them. The recovery team had finally dragged the captured Israeli tank, the one Vulov had requested, into a secure garage behind Syrian lines. It was a showcal, the Israeli name for the upgraded Centurion.

Vulov circled the beast. It looked battered. The paint was scorched. But as he climbed onto the engine deck, he realized the Western tank was a lie. This wasn’t the British tank they knew from World War II. “Open the engine bay,” Vulov ordered. The mechanics unlatched the heavy steel covers. Vulkoff expected to see the erratic, flammable meteor petrol engine that the British had originally installed.

An engine known for catching fire if you looked at it wrong. Instead, he stared at a massive air cooled American monster. It’s a diesel, the chief mechanic said, wiping grease from his hands. A Telodine Continental AVDS, Americanmade. Volov realized instantly why the Israeli tanks hadn’t burned as easily as the T-55 tanks.

Diesel fuel is much harder to ignite than petrol. The Israelis had taken a British chassis and transplanted an American heart into it. And the transmission? Volov asked. Allison CD850 automatic like a luxury car. Volov felt a chill. The Soviet T-55 and T62 tanks required brute strength to drive. The drivers had to hammer the gears with a sledgehammer.

Sometimes they were exhausted after 2 hours. The Israeli drivers with this American automatic transmission could drive for 24 hours with one hand on the yolk. They weren’t just fighting better, they were fresher. But the engine was just the beginning. Volov climbed into the turret. This was where the true secret lay. The thing that allowed a single tank to destroy a platoon in minutes.

He squeezed into the commander’s seat and looked at the breach of the gun. It wasn’t the gun itself that shocked him. It was what was missing. “Where is the computer?” Vulov asked. “Where is the auto loader?” “There was none. It was primitive. Manual cranks, a human loader.” “How?” Vulkov whispered. “How did they shoot faster than our autoloader?” He looked at the floor of the turret. It was covered in spent brass casings.

He looked at the layout of the ammunition racks. And then he saw the modification that changed everything. The Israelis hadn’t added technology. They had removed it. They had stripped the tank down to maximize the one thing the Soviets had neglected. The human factor. The shock was waiting for him in the gunner’s sight.

He put his eye to the rubber eyepiece. What he saw through the glass would explain why the Syrians felt they were fighting ghosts in the dark. It wasn’t magic. It was a piece of stolen technology that the Soviets had been warned about, but had arrogantly dismissed. October 10th, 1973. Behind Syrian lines, Colonel Vulov pressed his eye against the rubber rim of the Israeli gunner’s sight.

He expected to see a sophisticated electronic computer display, something that would explain the supernatural accuracy of the Zionist fire. He expected glowing red reticles, digital rangefinders, or perhaps a thermal overlay technology that the KGB rumors said the Americans were testing in Nevada. Instead, he saw a piece of glass. It was shocking in its benality.

The sight picture was clear, incredibly clear, but it was analog. There were no dancing lights, just a simple stadometric rangefinder, a set of lines used to estimate distance based on the size of the target. It was almost identical to the sites used in World War II. Volkov pulled back confused.

This is it, he asked the Syrian engineer. This is the ghost technology. It is a telescope. Look closer, Colonel, the engineer said, pointing to the ammunition rack next to the loader station. It is not how they see, it is what they throw. Vulov moved to the ammo rack. He pulled out a heavy, sleek projectile.

It didn’t look like the explosive shells the Soviet tanks fired. The Soviet T62 tank fired two main types of rounds. High explosive anti-tank heat and steel armor-piercing rounds. This Israeli round was different. It was the M392 APDS armor-piercing discarding Sabot. Volkov held the round and suddenly the physics of the Valley of Tears clicked into place. This was the secret.

This was the killer. The Soviet doctrine relied on the concept of slope. The T-55 and T-62 tanks were designed with heavily sloped frontal armor. The idea was that a traditional steel shell would hit the slope and bounce off or ricochet. It was a shield built on the laws of angles. But the APDS round in Vulov’s hand was a cheat code against physics.

The engineer explained, “It is a dart colonel wrapped in a shoe, a sabot. When it leaves the barrel, the shoe falls off. The dart travels at 1400 m/s. It is made of tungsten carbide. It concentrates all the kinetic energy of a massive gun into a point the size of a coin. Vulov realized the horror of the situation. The APDS round didn’t care about the slope of the T62 armor.

It moved so fast and was so dense that it didn’t bounce. It punched through the sloped steel like a needle through fabric. The invincible frontal armor of the T62, which gave the Syrian crew so much confidence, was paper to this weapon. and the gun that fired it. Vulov looked at the breach again.

Stamped into the metal was the designation Royal Ordinance L7. This was the twist that made Vulov’s blood run cold. The L7 gun wasn’t American. It was British, and it had been born from a Soviet mistake years ago. In 1956, during the Hungarian Revolution, a Soviet T54 tank had been driven onto the grounds of the British embassy in Budapest by panicked rebels.

The British had briefly examined it, realized their current guns couldn’t penetrate its armor, and immediately developed the L7 specifically to kill Soviet tanks. The Syrians were being destroyed by a weapon designed 15 years ago, specifically to hunt them. But the mystery of the night battle remained, the ghost attacks.

How did the Israelis see the T62 tanks in the dark without infrared gear? Vulov climbed out of the turret and walked to the front of the captured tank. He looked for the infrared search light. There wasn’t one. Instead, mounted above the main gun was a massive boxy xenon search light. They have white light, Volkov noted. Visible light. If they turn this on, they reveal their position to the whole world. It is suicide.

They didn’t use the lights, Colonel. A survivor from the seventh division spoke up. He was a platoon commander bandaged and smoking a cigarette nearby. They used our lights. Vulov froze. Explain. We were taught to use the active infrared,” the commander said bitterly. “We turn on the IR spotlight. We look through our scope. We see the world in green. But the beam, the beam is a flashlight.” Vulov understood instantly.

The Soviet active IR technology was a trap. To see, the Syrian tank had to project a beam of infrared light. To the human eye, it is invisible. But to anyone with a basic passive night viewer or even just looking closely at the source, the emitter glows a dull, angry red. And worse, when dozens of Syrian tanks turned on their IR beams in the dusty smoky air of the Golan, the beams crossed. They illuminated the dust. They created a silhouette effect.

The Israelis sitting in the dark didn’t need to see the tanks. They just aimed at the source of the invisible beams. Every time a Syrian tank commander turned on his advanced night vision to find a target, he was essentially lighting a flare over his own head that said, “I am here.” The Israelis were firing at the flashlights.

Volkov returned to the bunker to draft his preliminary report for Moscow. The conclusion he was writing was heresy. It contradicted everything the Communist Party taught about war. The Soviet philosophy of tank design was collectivist. The tank was a consumable asset. It was made to be small, hard to hit, and cheap to produce in massive numbers. The crew was secondary. The T62 tank was cramped.

The loader had to work in a space the size of a closet, lifting heavy shells while the gun breach recoiled inches from his chest. It was hot, loud, and terrifying. After 3 hours in a T62 tank, a crew was physically broken. Their reaction times slowed. Their loading speed dropped to two rounds per minute.

The western philosophy embodied in the show was individualist. The tank was huge. It was a barn, but inside it was an office. Vulov wrote furiously. The enemy tank is inferior in armor protection. It is inferior in top speed. It is a larger target. However, it possesses a decisive advantage. Ergonomics.

The Israeli loaders standing on a flat turntable floor in a high-roofed turret could grab rounds easily. They weren’t fighting the machine. The machine was working for them. This explained the rate of fire. While the Syrian loader was struggling to align a shell in a bouncing, cramped T62, the Israeli loader had already fired two rounds.

In the Valley of Tears, where the range was short and the targets were many, rate of fire was the only metric that mattered. The Israelis were putting three times more metal in the air than the Syrians. 100 tanks firing at 10 rounds per minute is equal to 300 tanks firing at three rounds per minute. The math balanced out not because of the number of tanks, but because of the number of shells downrange.

There was one final detail Volkoff included in his report, a detail that would eventually lead to the development of the T72 and T80 tanks. During the interrogation of the captured tank, the mechanics found a specific handle near the commander’s seat, the commander’s override.

In a Soviet tank, the commander commands, the gunner shoots. If the commander sees a target, he has to yell at the gunner, “Target left. Travis left.” The gunner then has to find it, aim, and fire. This loop takes seconds, crucial, fatal seconds. In the Centurion, the commander had a joystick. If he saw a threat, he could grab the stick, override the gunner, swing the turret himself, and put the gun on target.

He could practically lay the gun for the gunner. Hunter killer capability. Vulov wrote, “The Israeli commander searches for the next target while the gunner kills the current one. They are processing the battlefield twice as fast as our crews.” As the war drew to a close in late October 1973, the Valley of Tears remained in Israeli hands. The Syrian army had lost over 1,000 tanks in that sector alone.

The Israeli Seventh Armored Brigade had been reduced to a handful of operational vehicles, but they had held the line. Volov’s report was sent to Moscow. It caused a storm in the Kremlin. The T62 tank, the pride of the Red Army, the tank that was supposed to rush to the English Channel in a week, had been stopped by a 1,942 British chassis with a new engine.

The shock wasn’t that the Soviet tanks were bad. It was that they were designed for the wrong kind of war. They were designed for a massive rolling offensive across the flat plains of Europe supported by nuclear weapons. They were not designed for a chaotic hullown knife fight in volcanic rocks where individual crew skill and gun depression meant more than frontal armor thickness.

The mystery of the 100 stopping the 1,400 wasn’t a miracle. It was a triumph of systems integration. The Israelis had taken a tank, upgraded the engine to keep the crew fresh, upgraded the gun to penetrate anything, and trained their crews to exploit the terrain. The Soviets had focused on the hard stats: armor thickness, gun caliber, top speed.

The West had won on the soft stats: depression angle, crew comfort, rate of fire, and optical clarity. Years later, military historians would look at the Golan Heights as the graveyard of the quantity over quality doctrine. The site of hundreds of T62 tanks burning in the valley proved that in modern warfare, being seen first and shooting first matters more than how many friends you brought to the fight. The Soviet advisers left Damascus quietly.

They left behind a broken army and a shattered reputation. But they took with them the lessons that would build the next generation of warfare. They realize that you cannot automate victory. You still need a human in the loop and that human needs room to breathe. A gun that can depress and a shell that doesn’t bounce.

In the end, the Valley of Tears was saved not by a secret laser or a hidden missile, but by a tungsten dart and a diesel engine. The logic of the battlefield is cruel. It does not respect the price tag of the tank. It respects only the crew that remains effective when the world is burning around