On April 5, 1945, heavy rain fell on the headquarters of the Japanese Navy’s Hoshi Command. The staff officers of Admiral Semu Toyota stood around the operations table. Looking at the dispatch from the Imperial General Headquarters spread before them—those cold lines on thin paper bore the meaning of a death sentence, confirming that no one in this room would return.

Operation Ten-Go had been approved. The surface special attack force was ordered to proceed to Okinawa, carrying with them the faith and honor of the Imperial Japanese Navy. The mission was clearly written. The battleship Yamato would charge onto the beach, fight as a fixed fortress, and hold its position until completely destroyed.

Vice Admiral Kusaka quietly set down his teacup, reached for the secure phone, and issued the order to launch a mission he himself understood was hopeless. One battleship, one cruiser, and eight destroyers were assigned to face the U.S. Fifth Fleet encircling the southern waters. Across the ocean, the USS Bunker Hill, Enterprise, and Essex prepared to launch hundreds of heavy bombers.

No one in the Japanese command realized that this solitary mission would mark the beginning of the most devastating air attack ever conducted on a warship afloat. The Pacific War had already proven that the age of giant battleships was over; the sky had become the realm where the fate of the ocean was decided. When thunder rumbled in the distance, they understood that Yamato was no longer a symbol of victory but merely the final target in the tragedy of the Imperial Navy.

By April 1945, the Second Fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy was only a pale shadow of its golden age. Only one battleship remained operational—Yamato, the last pride of a navy that had once dominated the Pacific in the early years of the war. Musashi had been sunk six months earlier in the Sibuyan Sea when hundreds of American bombers turned the water’s surface into an inferno of steel and fire.

Shinano had been converted into a massive aircraft carrier, but survived only ten days before an American submarine ended it with four cold torpedoes. Meanwhile, USS Bunker Hill cut through the Pacific at 46 km/h despite its 27,000-ton hull. Rear Admiral Marc Andrew Mitscher stood silently on the bridge, gripping his binoculars as he read each new intelligence report.

Under his command was Task Force 58, possessing 386 aircraft spread across 11 fleet and light carriers. This force was designed to project American airpower across the vast ocean, turning each ship into a mobile airfield. F6F Hellcats provided fighter cover, SB2C dive bombers delivered strikes, and in the bays of the TBF Avengers lay the weapon that would change the course of naval warfare—the Mark 13 torpedo.

The Mark 13 was the product of three years of combat experience, vastly improved from early-war models that veered off course or detonated prematurely in the cold sea. The upgraded Mark 13 could be dropped at 482 km/h from 244 meters with stability. Each torpedo carried 272 kg of Torpex, enough explosive power to tear through the thick armor of the battleship Yamato.

American pilots were trained to concentrate their attacks on a single side of the ship, creating a deadly list that would render Yamato’s pumping systems completely unable to rebalance. On the carrier Enterprise, Commander Ramage meticulously studied Yamato’s structure, able to sketch its armor layout from memory. Born in Waterloo, Iowa, Ramage held a degree in aeronautical engineering and understood that technology was not merely knowledge—it was a decisive weapon in this war.

To sink Yamato required perfect coordination: torpedoes hitting below the armor belt, bombs precisely silencing every anti-aircraft gun. Success or failure depended on timing, approach direction, and overwhelming firepower concentrated in fleeting moments. On Yamato’s deck, Captain Kosaku Aruga read the mission order for the tenth time.

Each line engraved itself into his mind like a farewell to destiny. On April 6, Yamato loaded 3,400 tons of oil fuel at Tokuyama Depot for a journey with no return. Depot staff secretly pumped 60% capacity instead of the 40% allotted for a one-way trip—enough for round-trip on paper, but meaningless in reality. Aruga understood that only a few hours of combat maneuvering would consume all of it, vanishing into sea fire, unable to save the mission.

He had once commanded a destroyer at Midway and witnessed Akagi and Kaga burning red under the rain of bombs from American aircraft. Aruga knew what no one wished to say—that the sky had become the true enemy, and artillery and steel armor were relics of an era already gone. Yamato, displacing over 72,800 tons, ran on 12 Kampon boilers powering four enormous turbines.

Its 3,332 crewmen had survived air raids in Leyte Gulf and a near-sinking by submarine torpedoes in the perilous Philippine Sea. Despite its heavy armor and giant guns, Yamato could not escape its fatal weakness—helpless against multi-directional air attacks. On the other side, American carriers split into three task groups, moving like giant fan blades, encircling the southern Japanese waters—Groups 58.1 to the north, 58.3 to the east, and 58.4 accelerating behind.

Each carrier launched reconnaissance planes in expanding box patterns, weaving a vast surveillance network. In the radar rooms, technicians worked in 4-hour shifts, eyes fixed on screens filled with static and ghost echoes from storm-disturbed seas. Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Taylor had coordinated flight operations for 20 months, moving with reflex-like precision across the complex radio control panels.

He managed each squadron like a flawless dance. Hundreds of aircraft moved into position, forming a symphony preparing for the opening blow. Launch cycles were maintained every 90 minutes. Three layers of combat air patrol overlapped at three altitudes covering the target area.

Weather worsened by the hour. Squalls swept across the decks. Visibility fluctuated between 3 and 16 km, causing radar interference. On April 6 at 15:20, Yamato’s strike force departed Tokuyama. Ten ships cut through the waves. Light cruiser Yahagi led the formation, with the destroyers following.

Yamato held the heavy rearguard position. When news of the U.S. landing at Okinawa reached him, the Emperor had quietly asked whether the navy could still do anything to defend the homeland. That question became an unspoken command. Operation Ten-Go was the desperate answer, even though it could not alter the war’s outcome.

Vice Admiral Seiichi Ito, commanding the Second Fleet, opposed the mission. He knew it was essentially a suicide sortie. Only when informed that the Emperor himself expected action did he quietly consent, carrying loyalty greater than reason. As the fleet passed through the narrow Bungo Strait between Kyushu and Shikoku, the water beneath them dark as steel, two American submarines waited in the gloom.

Around 17:45, USS Threadfin, commanded by Joseph F. Enright, detected the Japanese force by radar. The enemy sailed at 41 km/h on bearing 240 degrees. The dense formation was easily identifiable on sonar. Threadfin surfaced briefly to send an urgent report, accepting the risk of interception by Japanese signals in order to prioritize speed over absolute secrecy.

The transmission went out clearly, informing the entire U.S. fleet of Yamato’s exact position as it headed south with its escorts. Further south, USS Hackleback took over shadowing duties, maintaining radio contact as the Japanese formation entered the East China Sea. Commander Swatek tracked every movement through the night, sending four position updates despite intense screening by Japanese destroyers.

Under the cold sea, sonar and radar became the eyes of the American navy, opening a hunt that lasted until the fateful dawn. Dawn on April 7, 1945, brought thick clouds as the first raindrops fell on Yamato’s deck. Clouds hung at 457 meters, visibility only 8 km, making radar struggle to distinguish rain from real targets.

Six fighters from Kagoshima reached the area at 6:00 a.m., providing aerial cover as planned. Their engines roared through the wet, heavy cloud layer. They could only protect Yamato for four hours and would depart at 10:00, leaving her alone on the ocean—with no shield against American airpower.

The fighters patrolled at 4,572 meters—nearly useless against low-level torpedo attacks. On U.S. flagship decks, the fleet commander ordered the battleships to prepare for the final surface engagement of the war. Six modern battleships with radar-guided 406 mm guns stood ready to confront the fuel-starved Yamato.

However, Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher, commander of the carrier forces, chose a different path—faster, and far more devastating. At 8:00 a.m., without waiting for authorization from Spruance, he ordered the carriers to launch the first wave from Bunker Hill. Hellcats and Avengers soared into the damp sky.

Hundreds of propellers chopped the sea spray into white mist. At 6:57, destroyer Asashimo sent an urgent signal that its engines had failed and began falling behind. Captain Kotaki of Destroyer Division 21 ordered emergency repairs, but the machinery was dead.

Hammering and metal clangs echoed in the engine rooms. Sailors struggled hopelessly as the ship slowed in foaming seas. Asashimo dropped behind. Its signal lights faded in rain while the rest of the force pressed toward Okinawa. At 10:00, Groups 58.1 and 58.3 launched the largest air strike in Pacific history—132 fighters, 50 heavy bombers, and 98 torpedo planes merged into a massive spear thrown from 11 carriers.

The fighters flew ahead to suppress the Japanese air defenses, clearing corridors for the bombers and torpedo planes. Heavy bombers attacked from multiple angles, forcing Yamato’s anti-aircraft guns to split their fire. The torpedo squadrons approached in coordinated lines, aiming at a single side to induce a fatal list.

Overhead, PBM Mariner scouts circled the battlefield, relaying Yamato’s coordinates to the U.S. fleet. At 12:20, Yamato’s lookouts spotted dark specks emerging from the gray clouds—American planes diving toward them. Every anti-aircraft gun swiveled upward.

At 12:32, Yamato fired nine 460 mm main guns, using Sanshiki anti-aircraft shells weighing 1,450 kg. The monstrous shells burst in midair, spewing thousands of flaming fragments forming a rain of fire. Yet the guns could fire only once per minute, while American attacks came every few seconds.

At 12:35, aircraft from USS Bennington and USS Hornet split to attack from different directions. Through pouring rain and foaming seas, Yamato emerged colossal—263 meters long with a superstructure rising 46 meters above the water. Every anti-aircraft gun erupted in red flame, weaving steel nets across the sky.

At 12:37, the first torpedo hit Yamato’s port side—a blast throwing a 30-meter column of water skyward. Two minutes later another torpedo struck midship, shaking the entire vessel as it began to list. A 454-kg bomb pierced the deck, igniting fires that spread uncontrollably.

Damage control teams fought desperately, flooding starboard compartments to counterbalance, but the attacks came faster than they could respond.

At 12:30, far astern, crippled Asashimo was found by planes from USS San Jacinto. It was struck repeatedly by bombs and torpedoes, engulfed in flame, and sank with all 326 crew—no survivors.

Thirteen minutes later, destroyer Hamakaze took a direct bomb hit on the bridge. The explosion killed the captain and most officers instantly. Burning and adrift, it was finished off by torpedo planes—240 crew dying with the ship.

Meanwhile, cruiser Yahagi was attacked by planes from three carriers, its engines destroyed, leaving it burning.

By 13:00, Yamato had been hit by at least five torpedoes—all on the port side where even thick armor could no longer withstand punishment. The list increased to 15 degrees despite counterflooding. The giant hull groaned as seawater surged in. Speed dropped to 33 km/h. Black smoke curled from mid-deck as Yamato struggled southward.

Far away, the second attack wave formed—100 more planes from Groups 58.1 and 58.3. Young pilots loaded with ordnance dived toward the wounded giant, now barely maneuverable—a massive target in the sea.

Torpedo squadrons coordinated tightly, approaching from three practiced angles, all aiming at the same port side to maximize hydrodynamic pressure and destroy balance.

At 13:42, three more torpedoes struck. Water and smoke erupted like volcanoes. Yamato’s list reached 20 degrees. The main guns leaned toward the horizon, unable to be trained. Seawater entered damaged hatches, unsealing compartments once watertight, disrupting weight distribution entirely.

In the control room, the assistant damage officer reported to Captain Aruga that counterflooding was futile. The ship was listing faster by the minute. All starboard compartments had already been flooded; no room remained to adjust.

Yamato now awaited her end. Vice Admiral Ito understood the inevitable had arrived. The ship could no longer fight. The sea was reclaiming the empire’s giant.

At 13:50, he ordered Operation Ten-Go cancelled—a bitter decision ending the navy’s last mission. Signal flags were raised in thick smoke, ordering surviving destroyers to rescue sailors. But Yamato’s radios were dead. Communication relied only on flags and lamps through smoke, fire, and towering waves.

At 14:02, Captain Aruga ordered abandon ship, but the 30-degree list made movement nearly impossible. Sailors slipped on the slanted deck, falling into boiling sea water, while others were trapped behind jammed or flooded hatches. The portrait of the Emperor was removed from the bridge and handed to a young officer, instructed to survive and return it to Tokyo. Executive Officer Jiro Nomura pleaded with Aruga to leave, but Aruga refused and ordered him to go.

Aruga tied himself to the compass stand with rope, choosing to remain with Yamato. Vice Admiral Ito quietly entered his cabin and closed the door behind him.

At 14:07, another torpedo struck the starboard side, though no one noticed—the ship already listed beyond 35 degrees. From the high side, men jumped 18 meters into the sea. Water exploded white beneath them as compartments burst.

The massive 460 mm main turrets, each weighing 2,774 tons, tore free and plunged into the deep.

At 14:14, Yamato rolled to 90 degrees, lying entirely on her side. The giant hull still slid forward at a few knots. Inside, hundreds were trapped in darkness, the steel compartments becoming death traps filled with heat and smoke.

At 14:17, the forward magazines detonated—a colossal explosion shaking the ocean. A towering fireball pierced the thick clouds. A mushroom cloud 6,100 meters high rose, visible from Kagoshima 160 km away—marking the death of a symbol.

Shockwaves rocked nearby American planes, a few sustaining minor damage from proximity. When the smoke cleared, Yamato was gone—only an oil slick and debris marked where she had once stood in glory and tragedy. Of Yamato’s 3,332 crew, only 276 survived; the rest sank with her.

Vice Admiral Seiichi Ito, Captain Kosaku Aruga, and most senior officers remained at their posts until the end. Destroyers Yukikaze and Fuyuzuki bravely returned under fire to rescue survivors. Fuyuzuki approached the burning destroyer Kasumi, its bow blown away, and fired a torpedo to scuttle the dying ship to prevent capture. Isokaze, motionless and burning, was also sunk by friendly fire—tragic acts preserving naval honor.

At 14:05, cruiser Yahagi sank after relentless attacks by hundreds of American aircraft. Only four of ten ships remained afloat; more than 4,137 Japanese sailors died in a battle lasting less than two hours.

American losses were only 10 aircraft and 12 aircrew—a perfect victory achieved through carrier airpower. In two hours, the U.S. Navy accomplished what surface battleships once required a full day to attempt—if they still had the strength.

The victory of Task Force 58 affirmed the maturity of aviation doctrine that had replaced cannons in modern warfare. Each strike was precisely coordinated among many carriers, concentrating power on one side of the target until Yamato’s defenses collapsed.

Three and a half years after Pearl Harbor, the prophecy of those who championed airpower had come true in one of the most magnificent scenes of destruction in the war.

For the Imperial Japanese Navy, the blow was not just military defeat but spiritual collapse—as Yamato, a name synonymous with the nation’s soul, disappeared. “Yamato” was an ancient name for Japan, and with the ship’s sinking, the last illusion of indomitable strength sank as well.

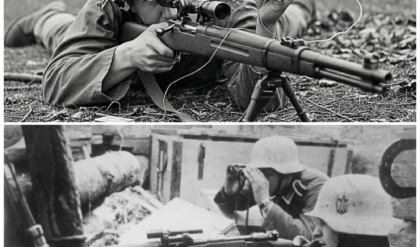

After the war, Admiral Sumiu Toyoda wrote that the failure of Operation Ten-Go marked the end of the navy as a fighting force. American intelligence played a decisive role; U.S. codebreakers read Japanese messages before many Japanese captains received their orders. Submarines were deployed in advance, patrol routes optimized, and surprise—war’s essential element—was lost to Japan.

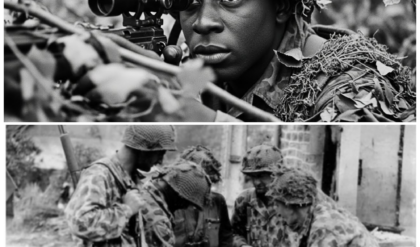

Training differences revealed industrial disparity: American pilots arrived with 300 hours of flight training; Japanese pilots averaged barely 100. U.S. squadrons rotated home to train new pilots, while Japanese aviators fought until death—no concept of return.

Ultimately, victory in the East China Sea was not only one of technology or tactics but of an era—when the sky replaced the ocean. After the war, the sinking of Yamato became a case study for every major navy, ushering in modern naval warfare. Strategists recognized that the battleship—a symbol of seapower for half a century—was obsolete, replaced by the might of aircraft carriers.

Technical reports concluded that air defense had to be rebuilt from the ground up as radar and radio communication proved equal in importance to guns and armor. In his campaign summary, Admiral Mitscher emphasized that perfect coordination among carriers was the key to overwhelming victory: eleven carriers launching planes within minutes required flawless timing to avoid collisions and interference.

These lessons formed the foundation for air operations in the Korean War five years later.

Amid the cold statistics, personal stories revealed human courage in the steel storm. Lieutenant Mitsuru Yoshida, one of the few survivors from Yamato’s bridge, later recounted how American pilots dove into anti-aircraft fire without hesitation. He wrote that their bravery matched any samurai who ever fought for honor—only they flew with steel and fire instead of sword and armor.

Captain Tameichi Hara of destroyer Yahagi, a survivor, described the battle as a tragic demonstration of the futility of absolute sacrifice.

Strategically, the failure of Operation Ten-Go meant Okinawa’s defenders lost all naval support, left at the mercy of overwhelming American force. U.S. casualties at Okinawa exceeded 50,000; the number could have been far higher had Yamato reached the landing beaches.

Its destruction on the way forced American planners to reassess Japanese resolve, recognizing their readiness for limitless sacrifice—even committing their last battleship to suicide. This understanding contributed to the decision to use atomic bombs four months later to end the war decisively.

In 1985, Japanese ocean archaeologists discovered Yamato’s wreck at a depth of 340 meters in the East China Sea, the bow planted vertically in the sand. The Imperial chrysanthemum crest remained visible, while the stern was shredded by the magazine explosion that destroyed the ship’s structure.

Modern analysis determined Yamato had been hit by 11 to 13 torpedoes and 6 to 8 bombs, mostly concentrated on the port side where she suffered fatal wounds. The most severe damage came from flooding, which spread through ruptured compartments, rapidly increasing the list and destroying all internal balancing systems.

In 1985, a special reunion took place between Yamato survivors and the American pilots who had attacked them. The Japanese veterans acknowledged that the mission had been doomed from the start, while the Americans expressed respect for the courage of men who knew they would not return.

At Kure, where Yamato had been built, a memorial was erected, attracting thousands annually to honor the crew. The Japanese come to bow in remembrance; Americans come to understand a former foe. The museum tells the story in the language of peace.

The 2005 Japanese film Yamato recreated the battle, portraying the heroic yet hopeless struggle of the crew in their final hours. Both Japanese and American perspectives hold partial truths—both a tragedy for the dead and a testament to the turning point of human military progress.

Today, about 1,000 tons of oil still remain in the wreck, leaking slowly into the sea—Yamato continues affecting the world even after 80 years. The wreck is considered a war grave, protected from salvage by international agreement to honor the dead.

Educational programs worldwide use the battle to teach the value of air superiority and the terrible cost of clinging to outdated doctrines. Military scholars view Operation Ten-Go as a prime example of how institutional pride can cloud judgment and lead to total destruction.

Technical analysis shows American aircraft operated with extraordinary sophistication. Torpedo planes attacked from optimal angles to penetrate underwater armor; dive bombers targeted communication and fire-control systems; fighters suppressed anti-aircraft guns in predetermined sequences. The battle was not chaos but a war symphony—each strike planned and synchronized to the minute.

Weather played a key role—low clouds forced bombers lower into anti-aircraft range but also helped conceal them. Rough seas hampered damage control on Yamato. Radar and communications were destroyed early, isolating the ship. Radio antennas were severed; signal flags were obscured by smoke and fire, speeding the collapse of order.

The leadership styles of those involved reflected their cultures—from Mitscher’s decisiveness to Ito’s absolute loyalty and Aruga’s self-sacrifice. Every small decision shaped the outcome. Now, in the deep East China Sea, Yamato lies silent.

Her giant guns are steel tombstones. The battle has passed, but the lessons remain: technology and coordination determine survival, while courage cannot replace material power. Pride misplaced leads only to destruction, and the fall of Yamato was not merely the end of a ship but of an era.

Operation Ten-Go failed in its tactical objective but succeeded in demonstrating the futility of fighting with obsolete concepts. Through the deaths of 4,137 Japanese sailors and 12 American airmen, Yamato accomplished her final mission—a warning to humanity echoing across the ocean: war is never glory, only the highest price mankind ever pays.