A hole dug with a shovel stopped an entire German armored attack. Sounds impossible, right? But it happened. On December 7th, 1,942, five Panzer 4s machines everyone believed were unstoppable rolled into a narrow pass that looked completely ordinary. No mines, no anti-tank guns, nothing threatening at all.

What the German crews didn’t know was that under the patch of ground they were about to drive over, an American soldier mocked by his entire unit as a stupid farm boy had hidden something no military manual ever mentioned. And in just 11 seconds, that stupid idea did what a whole artillery team sometimes couldn’t. December 7th, 1,942. A few hours before the German tanks appeared, Private Firstclass Samuel Sam Garrett was already awake, crouched beside the strange construction he’d spent the last nine days building at Fed Pass.

To anyone walking by, it looked ridiculous. Three uneven mounds of dirt, scattered scrap metal, and a patch of ground that seemed slightly too flat to be natural. No one in his unit took it seriously. In fact, for more than a week, this spot had been the single biggest joke in the battalion.

The first person to declare it worthless was First Sergeant Raymond Kowalsski, a man known for not sugarcoating anything. During inspection on day eight, he planted his boots in the dirt, stared at the setup, and unleashed a verdict that spread faster than the morning cold. Garrett, I’ve seen dumb ideas, but this this is the stupidest waste of time I’ve ever witnessed. It wouldn’t stop a Volkswagen, let alone a panzer.

” His voice carried across the pass, and the men nearby erupted in laughter. Almost immediately, word spread that Garrett, quiet ranch kid from South Dakota, had decided he knew more about anti-tank defense than the U S army. Lieutenant Colonel Marcus Pton, the battalion commander, wasn’t amused either. When he inspected the position 4 days earlier, he didn’t bother hiding his annoyance.

Private, we have mines. We have anti-tank guns. We have bazookas designed by people who actually understand how to kill tanks. What you’ve built is not a defensive position. It’s an embarrassment. He finished with a warning that cut deeper than all the jokes.

When the Germans attack this pass, your stupid farmer tricks are going to get people killed. Even Garrett’s own squad didn’t defend him. Corporal Dennis Murphy was the one who coined the nickname Garrett’s gopher mound. The name stuck. Soldiers passing the area deliberately detourred just to take a look and throw another jab. Hey Garrett, you building a playground or a defensive line? Need help planting corn on those dirt piles? First Panzer comes through here, it’ll roll right over your little sand castle. Private Leonard Shaw, never known for kindness, made the

harshest prediction of all. The tank crew won’t even bother shooting at you, Garrett. They’ll be too busy laughing. For 9 days, this was Garrett’s reality. He dug, measured, moved dirt, adjusted angles, hauled wood, and absorbed every insult the battalion could offer. But he said nothing because the men mocking him only saw dirt. They didn’t see the logic inside it.

What Garrett was building wasn’t meant to look impressive. It wasn’t meant to look like a weapon at all. It was meant to look ordinary, invisible, exactly the kind of ground a Panzer commander would trust. And on this cold morning, with German armor preparing to advance, the thing everyone laughed at was the only thing standing between the battalion and a catastrophe.

Before Tunisia, before the insults, before the panzer columns, Sam Garrett’s world was not steel and explosives. It was dirt, dry grass, open sky, a swel null null null, acre cattle ranch in western South Dakota. Predators were constant coyotes, prairie dogs, anything quick enough to tear into livestock or destroy fields. Ammunition was expensive. Misses mattered.

Mistakes cost money, not lives. But the principle was the same. Don’t waste your shot. And from a young age, Garrett learned that you didn’t outmuscle predators. You outthought them. His father drilled the lesson into him. You don’t kill prairie dogs by shooting at everything that moves. You kill them by knowing exactly where they’ll be before they know it themselves.

Prairie dogs always use the same paths. Coyotes circled downwind. Animals behaved in patterns, not because they were smart, but because they were predictable. And if you understood those patterns, you could place a trap made of almost nothing. Scrap wood, a shallow pit, a cheap charge, right where they’d step every single time.

Garrett grew up on that logic. It shaped how he saw the world. And in Tunisia, he saw tanks the same way he had seen predators back home. not as unstoppable monsters, but as heavy, predictable animals with blind spots. He noticed something early in the campaign. German Panzer crews behaved with the same consistency as the coyotes and prairie dogs he’d hunted for years.

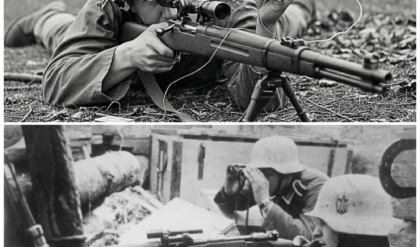

Panzer drivers stuck to the smoothest possible ground. They avoided rocks and harsh slopes that could throw a track. Commanders scanned from periscopes that gave narrow, distorted angles. Belly armor stayed hidden at all costs because it was the thinnest, weakest part of the tank, and in a narrow pass, a tank wouldn’t improvise. It would follow the path that felt safe.

When Garrett studied Fed Pass, everything clicked. Steep, jagged slopes boxed the corridor into a 40 meter wide channel. The floor of the pass had one natural line of travel, the smoothest section, just wide enough for a Panzer 4. Garrett walked it for days, tracing the route with his boots, imagining himself behind a vision slit, deciding where he would drive if he were the German tanker. The more he studied it, the clearer it became.

If German armor attacked through Fed Pass, there was only one path their first tank would take. So, he built his system around that inevitability. But while Garrett saw predictable movement, others saw chaos and improvisation. Infantry officers were trained to think in categories. Obstacles, mines, trenches, guns. Garrett’s construction didn’t fit any of them.

It looked like a child’s sand castle compared to the neat textbook diagrams of anti-tank defenses. Yet Garrett wasn’t building a thing. He was building a behavior trap. A system that didn’t force a tank to go somewhere, but let the tank choose the wrong path on its own. That was the genius.

And that was why everyone missed it. To Sergeant Kowalsski, Garrett’s mounds of dirt looked like a lazy attempt at roadblocks. To Lieutenant Colonel Patan, the covered pit looked like sloppy engineering. To the squad, the whole setup looked like a bad joke. They expected anti-tank defenses to look like anti-tank defenses. Garrett expected tanks to behave like animals.

So, while the others saw dirt piles, a suspiciously flat patch of ground, scrap metal arranged without apparent order, Garrett saw how a Panzer Four’s weight would shift as it tried to avoid a mound. He saw how the driver would instinctively correct course. He saw how a commander’s periscope would miss the slight color difference between real ground and camouflage.

He saw how gravity would tilt the hull once the front tracks broke through a disguised cover. He saw how a shaped charge aimed at a 40deree exposed belly could kill a tank that a bazooka team might struggle to disable. His father had once told him, “A good trap doesn’t look dangerous. It looks ordinary.

” In Fed Pass, that principle became a battlefield weapon. Garrett didn’t need the trap to look like a fortified position. He needed it to look like nothing at all. Just another strip of ground in a mountain pass. To the Germans, it would be safe. To his officers, it looked stupid. But to Garrett, it was the exact place where a predictable machine would put 45 tons of steel.

And if he was right, the moment those tracks touched that ordinary ground, everything would happen exactly as he calculated. To everyone else, Garrett’s construction looked like a mess. Three ugly mounds of dirt, a random patch of ground that seemed too smooth, and some buried scrap metal.

But beneath the jokes and misunderstandings was a system built with the precision of an engineer and the mindset of a hunter. Garrett didn’t build obstacles. He built choices. Choices that convinced a tank crew to drive exactly where he wanted them to go. And it all began with the most mocked part of the entire structure. The dirt mounds, not obstacles, but steering wheels. The three mounds were arranged in a simple curve across the pass.

Anyone with a military background dismissed them immediately. Tanks can go over dirt. Tanks can go around dirt. To a trained eye, these piles were useless. But Garrett wasn’t trying to block anything. He wanted the German driver seeing the mounds through a narrow vision slit to instinctively drift toward the smoother, safer looking path.

The mounds didn’t stop the tank. They guided it the same way a cattle fence line gently nudges livestock without forcing them. A Panzer 4 weighs 45 tons. You don’t redirect that with force. You redirect it with psychology.

And if the driver made even a slight course correction, the tank would be aligned perfectly for the second component, the covered pit. The heart of the ambush. 17 ft past the last mound was a patch of ground that looked perfectly normal. Same color, same texture, same distribution of rocks. But underneath Garrett had carved a rectangular excavation no feet deep fine feet wide diswit feet long.

The roof of the pit was a wooden lattice made of 2×6 planks spaced and braced based on careful math. Over the lattice he stretched heavy canvas painted with local soil. On top of that he added 6 in of real dirt and rocks gathered from the immediate surroundings so the shades matched exactly. Infantry could walk on it. Even a jeep might roll across without collapsing. But a Panzer 4 never. Garrett had run the numbers.

A combatloaded Panzer 4 produced ground pressure of to 5.8 kg per square centimeter. The wooden framework could barely handle 3 kg per square cime. The moment a tank’s tracks committed fully to the cover, failure was guaranteed. The collapse wouldn’t be dramatic at first.

It would begin with a subtle crack, then a sudden plunge as the front tracks punched through the canvas and the tank’s nose dropped sharply into the pit. When the panzer tilted down between 35° and 45°, gravity did the rest. At that angle, the thin belly armor just 8 mm thick became fully exposed, like lifting the soft underside of a predator.

Garrett had hunted enough animals to know it’s not about the size of the weapon, it’s about where you force the target to stand. Three, the shape charges, the killstroke. At the bottom of the pit, Garrett positioned four-shaped charges. These were not armyissue weapons. They were built from captured German explosives, each packed with about 12 lb of material and fitted with handshaped copper cones. He aimed each charge upward at a precise angle.

He calculated the correct standoff distance, the gap between the cone and the armor to ensure maximum penetration. When the tank’s nose collapsed into the pit and its weight triggered the contact switches, all four charges would fire almost simultaneously. A shaped charge isn’t a normal explosion.

It focuses energy into a narrow hypervelocity jet of molten copper traveling at to 7,000 m/s. Faster than a rifle bullet, hot enough to burn through steel like wax. Garrett knew that even one solid hit on belly armor could destroy a panzer. Four simultaneous hits would turn the interior into a storm of fire, metal fragments, and exploding ammunition. He wasn’t just trying to stop the tank. He was trying to erase it.

Four, the backup charges, the insurance policy. Garrett’s father had taught him something that applied perfectly here. A trap should kill twice. Once for the animal and once for the mistake you didn’t see coming. So Garrett installed six more charges around the perimeter of the pit.

These were linked to tension wires buried just beneath the surface. When the tank settled deeper after the first explosions after the hull twisted under its own weight, the wires would tighten and detonate the backup charges 3 5 seconds later. If the shaped charges somehow failed to finish the job, the perimeter charges would.

If the crew tried to escape, the perimeter charges would catch them. If the tank somehow remained recognizable, the perimeter charges would make sure it no longer was. The entire system, dirt mounds, camouflaged pit, shaped charges, backup blasts, was designed to function in a single chain reaction. A Panzer 4 with its armor, its doctrine, its commander’s habits, its drivers instincts would walk itself into the perfect kill position without realizing it.

Why, no one understood it. To Garrett, the system was elegant. To everyone else, it was nonsense. Officers expected neat, symmetrical, defensive works. Sandbags, gunpits, mines, trenches. What they saw instead was a crude, asymmetrical layout that didn’t match any manual. They saw dirt piles where there should be logs, a suspiciously perfect patch of ground where the pit lay hidden.

Novi mines, no wires, no obvious engineering logic. They judged the appearance, not the behavior it manipulated. And that was the entire point. A good trap doesn’t look like a trap. It looks like the safest possible choice. The German tank crews approaching Fed Pass would see nothing unusual. They’d follow the smooth path. They’d avoid the dirt mounds. They’d drive right over the safe ground.

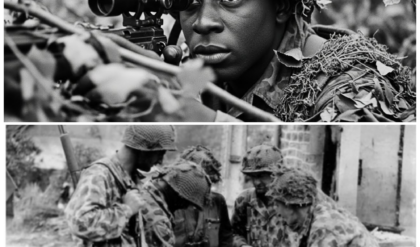

And the moment they committed 45 tons of steel to that spot, Garrett’s 9 days of ridicule would end in a single violent confirmation. Everything would hinge on whether his calculations were right. As German armor began concentrating east of Fedpass, Garrett’s quiet project stopped being a joke and became a problem. On December 3rd, a patrol returned with urgent news.

At least 12 Panzer Fours were forming up for an attack through the pass. A serious armored push was coming. Instead of validating Garrett’s work, the news made his position far more controversial. First Sergeant Kowalsski gathered the men for evening formation. His voice boomed across the cold air. The Germans are bringing a dozen panzers.

Garrett’s dirt pile is going to save us all or it’ll get us all killed while he learns that hunting gophers in South Dakota doesn’t qualify him to fight tanks in Tunisia. Men laughed, but the tension underneath was real. German armor wasn’t a rumor anymore. It was hours away. Lieutenant Colonel Peton reacted even more forcefully.

By 1800 hours, Garrett was ordered to report to battalion headquarters. He walked into the tent expecting another lecture. What he got was an ultimatum. Peton’s voice was flat, controlled, but unmistakably angry. Private German armor will attack through this pass within 72 hours. Your construction is sitting exactly where it disrupts our real anti-tank defenses. The colonel stepped closer.

I am giving you 24 hours to fill in your holes, scatter your dirt piles, and clear the field of fire for our guns. If you refuse, I will have you court marshaled for disobeying orders in combat. That is not a threat. That is a promise. The words hit harder than any insult. This wasn’t mockery anymore.

This was the line between obedience and criminal charges. Garrett stood at attention. Yes, sir. 24 hours. But as he saluted and left, something became painfully clear. The colonel didn’t understand what Garrett understood. The trap wasn’t in the way. It was exactly where it needed to be.

Fed Pass narrowed into a single usable corridor about 40 m wide, boxed in by steep, rocky slopes. Tanks couldn’t climb the sides. They wouldn’t risk rolling onto uneven ground. They would always choose the smoothest line through the valley. Garrett had walked that line for weeks. He knew every rock, dip, and angle. He knew the exact moment a panzer would correct its path. He knew the precise point its weight would commit forward.

If he moved the trap even a few meters, the entire system would collapse, not the tank. So that night, instead of dismantling anything, Garrett went back to work alone in the dark under the weight of an order that could ruin his life. He checked the framework again and again, walking across it to confirm it held infantry weight but not tank weight.

He retouched the camouflage so that no shadow looked unnatural. He retested each shaped charge, each firing wire, each tension line for the backup explosives. He brushed away footprints. He blended the edges. He worked with the calm of a man who understood one thing clearly. If the trap failed, the Germans would break through and the colonel would be right.

men would die and Garrett would face charges on top of it. But if the trap worked, if the system behaved exactly as he calculated, then everything they said about him, every insult, every joke, every threat would collapse as surely as the wooden lattice beneath a panzer’s tracks. By dawn, his decision was made. He would not dismantle his trap.

He would not move it. He would face court marshall before he betrayed what he knew to be true. And the moment the first tank touched the wrong patch of dirt, every man in the battalion would finally understand why. Dawn on December 4th arrived with the kind of cold that bit straight through a man’s jacket. Garrett had barely slept.

Before first light, an orderly found him. Private Garrett. Colonel wants you at headquarters. Now, this time Garrett expected the worst. He walked in imagining the start of court marshal proceedings, but instead of anger, he saw something unexpected.

Lieutenant Colonel Peton hunched over reconnaissance reports, brows furrowed, eyes fixed on the maps of Fed Pass. The colonel didn’t look up at first. He simply asked, “Private? I ordered you to dismantle your trap. Did you do it?” Garrett stood straight. No, sir. Peton finally met his eyes. Why not? Garrett didn’t hesitate. Because the Germans will attack through that pass, sir, and the trap will stop them. Silence.

More than silence calculation. For several seconds, the colonel studied the young private as if seeing him properly for the first time. A farm boy from South Dakota standing there in dusty boots, calmly refusing a direct order in wartime. Then, Paton pulled out a chair. Sit down, private.

Explain to me exactly how your pile of dirt is going to stop a panzer, Garrett sat. And for the next hour, he did something he’d never done before. He taught. He explained the dirt mounds not as obstacles, but as steering mechanisms. He described the precise angles he’d measured to funnel the tank toward the ordinary patch of ground.

He laid out the loadbearing math, how much weight a Panzer 4 puts on each track, how much the wooden lattice could withstand before catastrophic failure. He showed maps he had drawn by hand, tracing tank behavior like an animals migratory path. He explained the shaped charges, 12 lb of German explosive each, copper cones formed at 60° angles, standoff distances calculated for maximum penetration through 8 mm of belly armor.

He demonstrated the backup charges, tension wires, timed fuses, the double kill principle he learned from his father. He walked Peton through every detail from camouflage patterns to soil matching to sun direction. When he finished talking, the tent felt strangely quiet. The colonel didn’t speak at first. He just looked at the map, then at the private who had spent 9 days building something the entire battalion mocked. Finally.

Private Garrett. If you’re right, you may have just designed a system that changes how we defend against tanks. Another pause. And if you’re wrong, you’ve wasted nine days of manpower and may get soldiers killed. Peton stood, hands behind his back. I’m not ordering you to tear it down. Garrett blinked just once. But listen carefully, Pin continued.

If your trap fails when the Germans attack, I will court marshall you. No hesitation, no leniency. Yes, sir, Garrett said quietly. Understood. Three days of waiting. For the next 3 days, German activity increased. Engines, movement, artillery repositioning. Patrols reported more armor, massing east of the pass.

The entire battalion knew the attack was imminent. Garrett used every minute. He crawled over the site again and again, adjusting camouflage until the covered pit blended perfectly from every angle. He tested the tension wires. He confirmed the firing circuits. He built his foxhole in a spot where he could observe the trap without being exposed.

Other soldiers preparing defenses still wandered past to taunt him. Corporal Murphy yelled across the pass, “Garrett, I hear the Germans are bringing their whole Panzer division. That’s 50 tanks. Your dirt pile ready for 50? Garrett didn’t even look up. It only needs to stop the first one, he said. The rest will rethink their life choices.

The men laughed, but a different kind of laugh now. More nervous, less certain. On the evening of December 6th, battalion headquarters received final confirmation. Artillery preparation 030 hours. Armor advance 04000 hours. Primary attack axis fed pass. Garrett moved into his observation position at 02000.

In the moonlight, the field looked exactly as it needed to look. Nothing out of the ordinary. No pattern, no sign of engineering, just another stretch of ground in a quiet mountain pass. To the Germans, it would appear safe. To the Americans, it was still a joke. To Garrett, it was the moment everything he had calculated was about to be tested under the weight of 45 tons of steel, and he knew exactly how much depended on being right.

Lieutenant Colonel Pettin was not an easy man to convince. He had fought in North Africa long enough to know what stopped a tank and what didn’t. Mines stop tanks. Anti-tank guns stop tanks. Terrain sometimes stop tanks. but dirt piles, wooden frames buried under a thin blanket of soil. It took a special level of audacity or insanity to claim that would work.

Yet something about Garrett’s confidence lingered with the colonel after their conversation enough that on the morning of December 4th, instead of filing court marshal paperwork, Patan summoned the private for a second discussion, not to punish him, but to understand him. When Garrett entered, Patton pointed at the chair again. Sit down. Explain it one more time. I want every detail, Garrett did.

But this time, he wasn’t defending himself. He was teaching a superior officer how his system functioned. The dirt mounds, behavioral steering. Garrett started with the three mounds. He explained how tanks behaved, not theoretically, but in the real world, how drivers instinctively avoided uneven ground.

how commanders preferred smoother paths because they improved speed, reduced track wear, and lowered the risk of slipping. He showed the colonel where each mound nudged a tank’s line of travel, shifting the vehicle a few degrees at a time until its nose pointed directly at the covered pit. It wasn’t force, it was suggestion. Tanks move like cattle, Garrett said. You don’t push them, you guide them.

The covered pit physics versus steel. Then he described the pit dimensions, angles, wood placement, the 6 in of top soil. He didn’t use engineering jargon. He used plain logic. A panzer puts almost 6 kg of pressure on every square centimeter of ground. My framework can only handle half. It’ll hold a man.

It won’t hold a tank. Peton leaned closer. Garrett pointed to a sketch he’d drawn of the tank’s profile. When the nose breaks through, it drops at least 9 ft. That puts the belly armor. He tapped the underside of the drawing right here, exposed at the perfect angle. Peton rubbed his chin. He understood angles. He understood armor.

And he understood that belly armor was the Achilles heel of any tank. The shaped charges, precision by improvisation. Garrett moved on to the charges. He explained how he shaped the copper cones, how he scavenged German explosives and repurposed them, how standoff distance amplified the molten jet, how a 45tonon tank suspended nose down would not escape the blow.

Three of the four jets should penetrate, one will hit the transmission, another near the commander, a third inside the ammunition racks. If any of that cooks off, he didn’t finish the sentence. He didn’t have to. Peton had seen destroyed tanks before. He knew what internal ammo detonation meant. The backup charges, redundancy. Then Garrett explained his father’s rule. A trap needs a second punch in case the first doesn’t land.

Six perimeter charges, tension wires, 3 to 5 second delay. Enough to finish anything that survived the initial strike. Peton blinked. Not because the idea was reckless, but because the idea was complete. It wasn’t random. It wasn’t sloppy. It was a fully integrated kill system built from nothing but logic, experience, and dirt. The terrain, the deciding factor.

Finally, Garrett walked Peton through the pass itself. He showed the colonel the natural bottleneck. He traced the smoothest track line. He demonstrated how the rocks, slopes, and ridges all forced the same decision. The Germans had only one viable route, and that route went straight across his trap. Peton stared at the map for a long time.

Then he asked, “Private? How sure are you?” Garrett answered the same way he had the first time. “100%, sir.” The colonel’s decision. Peton closed the folder. He paced once, twice, then stopped. “All right, your trap stays.” Garrett didn’t breathe for a moment. But understand this, Peton continued, voice firm. If it fails, if even one tank gets through, I will personally ensure you face court marshall.

Understood? Garrett nodded. Yes, sir. The colonel held his stare for several seconds, then dismissed him with a brief wave. When Garrett stepped out of the tent into the cold sunlight, he felt the weight of that decision more than any insult he’d taken in 9 days. If his trap worked, he’d save the battalion.

If it failed, he’d be remembered as the farm boy whose arrogance cost lives. No more jokes, no more laughter. Everything was on the line, and the Germans were already moving. By the evening of December 6th, the waiting was over. Intelligence confirmed it. The Germans would strike at dawn. Artillery barrage at 030 hours. Armor advancing at 04 0. Primary axis, Fed Pass. Every man in the battalion felt the pressure tighten like a fist.

But for Garrett, the tension was sharper. His entire future hinged on a patch of ground disguised as nothing. The final pre-dawn hours. At 020 0, Garrett climbed into his observation hole, a shallow depression just deep enough to hide him, but positioned perfectly to watch the trap unfold. He looked across the moonlit pass.

The three dirt mounds sat quietly, casting soft shadows. The covered pit blended so perfectly with the terrain that even Garrett, who had built it by hand, struggled to see its outline. From a tanker’s perspective, 15 ft higher with only a narrow periscope slit to view the world. It would appear completely natural. No one else believed this thing was real. Not truly.

Even those who had stopped mocking him still didn’t understand it. But Garrett knew the trap didn’t need to look dangerous. It needed to look harmless. Three, the first sign. Right on schedule, German artillery began firing. The bombardment was heavy but short. 15 minutes of concussive blast slamming into American positions along the ridge.

The air shook with each impact. Dust rained down. The ground trembled. Garrett pressed himself flat as shells detonated around him. None landed close enough to threaten the trap. The pit remained intact, the charges untouched. Then at 0315, the artillery fell silent, and in the quiet that followed, Garrett heard it.

A deep rumbling growl, slow, rhythmic, mechanical, tank engines, multiple, close. The sound carried through the pass like a warning. 3 20. The column appears through the dark, he saw them. Five Panzer fours moving in column formation, advancing cautiously through the pass.

Just as intelligence predicted, the lead tank rolled forward with its commander half exposed in the Koopa, scanning the terrain. The driver followed the smoothest ground, avoiding rocks and uneven slopes, exactly as Garrett had calculated. The tanks were close enough now that Garrett could feel the vibration of their tracks through the earth. The lead panzer was roughly 300 m away, then 250, then 200.

The mounds did their work quietly. Without looking dangerous, they nudged the tank’s path a few degrees left, then a few more. From the commander’s vantage point, nothing seemed odd. The ground ahead looked as solid and ordinary as the rest of the pass. Garrett’s heartbeat hammered against his ribs.

3 hours 19 minutes and 45 seconds, the final approach. At just under 40 m, the lead tank reached the first mound. The driver adjusted course slightly to avoid it. That small correction aligned the tank perfectly with the center of the disguised pit. Garrett had predicted this exact movement. He had built the mounds for this exact moment.

Every step of the tank’s approach matched his calculations. Speed, steady, angle, correct, course, committed. There was no turning back without making a dramatic maneuver that would alert the rest of the formation. They were locked in. 3 hours 20 minutes. Point of no return. The panzer’s front tracks reached the edge of the covered pit. For 2 seconds, nothing happened.

The wooden framework flexed under the massive weight. A soft groan lost under the rumble of the engine. The tank continued forward, tracks grinding across dirt and canvas. For a brief, terrifying moment, Garrett wondered if he had miscalculated, if the planks might hold, if the cover was stronger than he thought.

Nine days of work hung on a razor’s edge. Then, a sharp crack, a sudden drop, a flash of sparks. The framework collapsed. The panzer’s front end plunged into the pit, tilting the entire hull downward at a violent angle. The rear tracks lifted off the ground as 45 tons of steel pitched forward. Garrett didn’t need to see the inside to know what would come next. He had built it. He had wired it.

He had placed every charge himself. The trap was no longer a theory. It was happening. And in the next 11 seconds, the pass would erupt. When the panzer’s nose punched through the false ground, time seemed to distort. To the German crew inside, the drop probably felt like a nightmare.

sudden, violent, impossible to understand. To Garrett, watching from his foxhole, it looked exactly like the diagrams in his notebook. 3 hours, 20 minutes, and 2 seconds. The drop. The moment the lattice collapsed, the front of the tank plunged straight down into the 9- ft pit. The hull snapped into a 42° nose down angle, the exact range Garrett had calculated.

The tank’s rear lifted off the ground. Its tracks spun uselessly in the air, kicking dirt. The heavy hull slammed against the sides of the pit, locking it into place. Inside, the driver was thrown forward against his controls. The commander in the Koopa was jerked downward violently, losing his balance. A Panzer 4 was not designed for this posture.

Nothing about its structure or weight distribution was built for a vertical drop. But Garrett had planned for this moment. Gravity was now the real weapon. 3 hours, 20 minutes, and 3 seconds. The first detonation, as the tank’s belly slammed into the bottom, two metal triggers beneath the camouflage snapped under the impact. Instantly, all four-shaped charges fired upward from the base of the pit.

A shaped charge is not a simple explosion. It is a weapon that turns copper into a molten needle thin jet at 7,000 m/s, nearly seven times the speed of a rifle bullet. Four jet punched upward. The first tore through the driver’s position, killing him instantly and obliterating the transmission. The second cut upward beneath the commander’s station, ripping through the turret basket.

The third struck the ammunition rack stored low inside the hull. That one mattered most. 3 hours 20 minutes and 4 seconds ammunition to cook off. Inside the tank, it took less than a second for the heat and shock to ignite the stored rounds. A pouncer 4 carried 72 rounds of 75 mm ammunition to 3,000 rounds of machine gun ammunition.

When those rounds cook off inside a confined metal box, the result is catastrophic. The explosion tore upward through the turret, blasting it off the hull entirely. The turret spun as it flew, landing more than 30 m away, throwing flames and fragments across the pass. The hull bulged outward, armor seams peeling back like torn metal pedals.

Fire erupted through every hatch, seam, and opening. The blast lit the entire pass with a pulse of orange light. For the German crew, death was instantaneous. Coxya sad. Backup charges detonate. 5 seconds after the shaped charges fired, the perimeter charges triggered automatically.

Six separate blasts erupted around the pit, designed to kill any surviving crew attempting to escape, but there were no survivors. Instead, the secondary explosions widened the pit, shattered the remains of the hull, and blew additional debris across the pass. What had been a 45tonon armored vehicle 13 seconds earlier was now an inferno of broken steel and burning fuel. 3 hours 20 minutes and 15 seconds.

Silence and shock. The entire sequence lasted 11 seconds. Garrett watched flames climb into the early morning darkness. Everything he calculated, angles, weight distribution, explosive timing, damage radius had worked perfectly. not just well perfectly but the moment of celebration wasn’t his because the second tank in the German column was still there.

The second Panzer stops in panic 50 m behind the first tank. The next Panzer 4 hard. The commander had seen the lead vehicle behave normally and then vanish into an explosion he couldn’t comprehend. to his eyes. There was no visible mine, no crater, no obvious source of the blast, no shell impact, no smoke trail, no muzzle flash.

It looked like the ground itself had killed the tank. That made it worse than a minefield. It made it unknown. The three trailing tanks stopped as well, forming a stalled column. According to standard German armored doctrine, the second tank should investigate.

But how do you investigate something you can’t see? The covered pit, now exposed by the explosion, still looked like normal terrain, except where the tank had torn through it. There were no wires, no charges, no clues, only a flaming crater and a missing turret. From the German perspective, the Americans had deployed a type of weapon they had never encountered. The Germans attempt a bypass. At 335, the second Panzer’s commander made a decision.

He tried to bypass the destroyed tank by steering left toward the slope, but Garrett had predicted this exact reaction. The dirt mounds weren’t just designed to funnel the first tank. They were positioned to channel any bypass attempt toward the second covered pit he had secretly excavated.

The moment the second tank committed to the alternate route, its tracks rolled toward that second disguised patch of ground. At 338, the second pit collapsed. The second panzer dropped. The second set of charges fired and the pass filled with another fireball. Two panzers destroyed. 19 seconds total. The remaining three tanks reversed immediately, desperate to escape what they believed was an invisible anti-tank minefield.

The moment the second Panzer vanished into a blast of fire and shrapnel, the entire German attack unraveled. The remaining three tanks didn’t wait for instructions. They didn’t push forward. They didn’t look for an alternate path. They simply reversed hard. German doctrine emphasized aggression.

But it also demanded caution when the lead tank was destroyed by an unknown threat. And this wasn’t just unknown. It was invisible. To the German crews, it looked as if American forces had deployed a minefield that left no crater, explosives that detonated upward, and a system that destroyed tanks instantly and without warning. No training manual had ever warned them about a weapon like this. 340. A wall of burning steel.

By the time the third and fourth tanks backed away, the entire pass was clogged with smoke and flame. Two panzers burned fiercely, their ammunition still popping from the heat. Armor plates glowed red. The smell of fuel and burning rubber filled the air.

The exploding turrets and rising flames turned the narrow mountain corridor into a furnace. At 200 m away, First Sergeant Kowalsski slowly stood up in his foxhole, staring in disbelief. This was the same man who had spent nine days calling Garrett’s idea the dumbest thing he’d seen in 14 years of service. Now he was watching two German tanks destroyed faster than any anti-tank gun he’d ever operated.

Murphy and Shaw, the loudest voices, mocking Garrett, looked equally stunned. No one spoke. The pass was sealed. The German attack had stopped cold. And nothing, no artillery, no infantry push, no armor breakthrough could pass that burning wreckage now. Garrett, how many tanks? Kowalsski eventually forced himself to walk toward Garrett’s position.

He climbed up the slope, boots crunching on gravel, eyes fixed on the destruction. Garrett was exactly where he’d been the entire time, lying still, observing, taking notes in his small notebook as if this were just another calculation to verify. The sergeant stood beside him, throat dry. Garrett, how many tanks? Garrett didn’t lift his eyes. Two, surgeent.

Both destroyed in primary trap sequences. Kowalsski stared at the burning pass again. He whispered at first, almost to himself, “Your stupid farmer tricks. just destroyed two panzers. Garrett nodded quietly. Yes, Sergeant. They functioned exactly as calculated. Kowalsski blinked, stunned. I called your trap the dumbest idea I’d ever seen. Garrett didn’t respond.

Kowalsski finally exhaled. I was wrong. That wasn’t dumb. That was the most effective anti-tank system I’ve ever seen. Word spreads through the battalion. By first light, half the battalion had gathered near the pass. officers, NCOs, engineers, even cooks who had heard the explosions. They stood on the ridge, pointing, whispering, trying to understand how one private with dirt, wood, and captured explosives had done what textbooks said required mines, anti-tank guns, or entire artillery batteries. Lieutenant Colonel Peton arrived next. He walked toward the smoking ruins, boots sinking into

blackened mud, eyes scanning the destroyed tanks. He moved in silence for several minutes, inspecting the collapsed pit, the exposed charge positions, the blasted perimeter wires. It was exactly as Garrett had described. Every detail matched the private’s explanation. Finally, Peton spoke, not loudly, not angrily, just a quiet acknowledgement.

Private Garrett has demonstrated exceptional understanding of physics, engineering, and enemy tactics. He wrote the rest in his afteraction report later that morning. His improvised anti-tank trap system achieved complete destruction of two enemy tanks using materials costing less than $50 recommend immediate promotion and assignment to engineering section. And the Germans on the German side, panic ran far deeper.

Recon reports captured months later described Fedpass as Amrichan’s Fort Gashrittas Unbar’s pancer oper American advanced invisible anti-tank minefield system to them. This wasn’t improvisation. It was a new American weapon, one they couldn’t detect, couldn’t understand, and couldn’t bypass. It wasn’t true.

But it didn’t matter. Fear changes doctrine faster than facts. And that fear had just begun. Morning light finally pushed through the smoke hanging over Fed Pass. Two Panzer Fours still burned, their twisted armor glowing in the weak sun. Flames licked out of shattered seams. Ammunition inside occasionally snapped and cracked like distant popcorn.

The pass was completely blocked, a wall of burning steel and broken machinery. No German force would be pushing through today or tomorrow or any day soon. But the greater shock wasn’t on the German side. It was inside the American lines. The battalion wakes up to a new truth. By sunrise, officers from other companies were making their way up to the ridge for a closer look.

They walked in small groups, pointing at the collapsed pits, the torn up earth, the blasted charges. None of it resembled any anti-tank defense they’d been trained to recognize. Some crouched down to touch the soil. Some stared at the melted copper remnants of shaped charges. Some simply whispered to themselves, unable to make sense of the destruction. “Who built this?” one lieutenant asked.

“Just one guy?” Someone replied. “Garrett the farm kid?” the lieutenant blinked. That can’t be right. But it was. Word spread rapidly. One private dirt scrapwood captured explosives. Two dead tanks. Zero shots fired. The story seemed absurd, but the evidence was right there, burning in front of them. The colonel’s inspection.

Lieutenant Colonel Peton approached the site with a different expression from the rest. No disbelief, no confusion. He had heard Garrett’s explanation in detail. He knew what he was looking for. He crouched near the collapsed pit, examining the remaining wooden lattice, the angles of the debris, the scorch marks from the shaped charges.

He traced the wiring with his gloved fingers, checking how Garrett had routed each connection. Every detail matched exactly what Garrett had described two days earlier. He straightened up, scanning the pass one more time. Garrett stood nearby, waiting silently. The colonel didn’t speak immediately.

He simply looked at the destruction, then back at the private who refused to dismantle his creation. Finally, Private Garrett. Garrett braced for the worst. The colonel continued, “I underestimated you. It was the closest thing to an apology an officer of his rank would ever give.” Later that morning, Peton wrote the afteraction report that would become famous.

“Private Garrett has demonstrated exceptional understanding of physics, engineering, and enemy tactics. His improvised anti-tank trap system achieved complete destruction of two enemy tanks using materials costing less than $50. And at the bottom, recommend immediate promotion. Recommend assignment to battalion engineering section. It wasn’t just praise. It was recognition that Garrett’s stupid farm trick had proven more effective than standard anti-tank doctrine.

The sergeant’s reckoning. First Sergeant Kowalsski returned to Garrett’s position later that morning. His face held none of the smug confidence from earlier days. He stopped beside Garrett, staring at the burning Rex. Garrett, he muttered almost reluctantly. Back there.

I called your idea the dumbest thing I’d ever seen. Garrett didn’t reply. Kowalsski shook his head slowly. Turns out I was the dumb one. That wasn’t a joke. That was the best damn anti-tank system I’ve ever witnessed. It wasn’t a speech, wasn’t flowery, just an honest admission from a man who had seen enough battles to know what real effectiveness looked like. And for Garrett, that meant more than the promotion.

The German interpretation far away on the German side, the reaction was completely different. Thereafter, action notes captured months later described Fed Pass as Pansa, American invisible anti-tank defense system. They believed the Americans had developed a brand new undetectable anti-tank minefield.

They believed it used multiple charges, redundant fuses, and upward blasts specifically designed for belly armor. They had no idea it was the work of one private with ranch instincts. Fear filled the rest of their report. Standard reconnaissance procedures and suficiant armored attacks through confined terrain no longer reliable.

Garrett had not only killed two tanks, he had changed enemy behavior, and he had done it using principles no manual had ever taught. Fed Pass stayed silent for the rest of the day. No more German armor pushed forward. No reconnaissance patrol approached the Rex, and no soldier, American or German, doubted the outcome anymore. But Lieutenant Colonel Peton wasn’t interested in celebrating. He was thinking ahead.

If one improvised trap could do this, what could several do? A new mission. On December 9th, supply trucks arrived carrying engineering materials, lumber, canvas, wire, and captured explosives. Instead of handing them to the battalion’s official engineers, Paton walked straight to Garrett. Private, actually, Corporal Garrett. Garrett looked up, surprised. You’re being promoted and you’re being reassigned.

Your job now is to build more traps. as many as possible. How many can you make with what you see here? Garrett studied the supplies for a moment. Three full systems, sir. Each taking around 8 to 10 days to build. Peton nodded. Good. You have 3 weeks. Build them and train men so they can build more when you’re not there. Garrett saluted. This time, nobody laughed.

The team of four. The colonel assigned him four assistants. Ironically, they were the same men who mocked him the most. Corporal Murphy, who had named it the Gopher Mound, Private Shaw, and two others who spent nine days joking about his dirt.

But something inside them shifted after witnessing two panzers obliterated by a farm boy’s design. Murphy was the first to speak up. “Sir, I want to learn how he builds these traps. I was wrong. I want to understand it.” Garrett didn’t hold grudges. He just nodded and began teaching. To their surprise, there was no magic, just logic, behavioral channeling, soil matching, structural collapse timing, explosion geometry.

The same men who mocked him now listened with absolute focus. Murphy turned out to be excellent at camouflage, better than Garrett expected. He matched rock patterns, dirt coloration, and shadow angles with near perfect accuracy. Garrett taught them the principle. If the ground looks even 1% wrong, a tanker will notice it.

Your job is to make the wrong ground look perfectly right. The second trap system, north route. The second system was built on a northern approach route. Intelligence suggested the Germans might attempt a flanking maneuver there. Garrett designed this trap with two pits in sequence. The first to catch the lead tank, the second to catch the inevitable bypass attempt.

He calculated the distance between them based on panser turning radius evading behavior average corrective path. It was fed pass all over again but with improvements and the improvements mattered. On January 3rd, three German tanks advanced along that northern route. The first hit the primary pit and was destroyed instantly. The second tried to bypass, turned exactly where Garrett predicted and fell into the second pit.

The third reversed into debris from the first explosion and immobilized itself. Three tanks neutralized. Zero American casualties. The third trap system, Western approach. The third system was even more advanced. Garrett arranged three pits in a triangular formation. One for the lead tank, one for the bypass, one for the bypass of the bypass.

You could not escape it without leaving the road entirely. and leaving the road meant certain track damage. Every angle, every mound, every camouflage patch was shaped by the lessons from Fed Pass. On January 11th, a German armored reconnaissance patrol stumbled into this third trap. Four Panzer Fours entered the approach.

The first tank triggered the center pit and exploded immediately. The second and third tried to bypass each, triggering one of the flanking pits. The fourth attempted to reverse quickly and backed into a boulder, tearing its transmission apart. Four tanks eliminated. One boulder assisted.

Seven tanks in total destroyed across the second and third systems. German radio total breakdown. Intercepted German communications revealed something extraordinary. Total loss of confidence in attacking through narrow terrain. One message later translated read, “American defensive positions in confined terrain employ anti-tank trap systems of unprecedented effectiveness. Standard reconnaissance procedures are inadequate.

Losses exceed acceptable limits by factor of five. Recommend suspension of armored attacks through mountain passes.” Garrett hadn’t just built traps. He had built fear. And fear was now doing more damage than explosives. When the smoke of Tunisia finally cleared, Garrett’s traps were no longer some strange farm experiment. They were a case study.

Army engineers, intelligence officers, and even generals began requesting briefings, not to mock him, but to learn exactly how he had done it. The Army Corps of Engineers eventually conducted interviews, diagrams, simulations, and post-action analysis on every trap he built. The findings were blunt. Behavioral prediction was more powerful than brute force.

Visual deception mattered more than thick armor. Redundancy mattered more than a single perfect weapon. Psychology could shape an entire battlefield. What Garrett had built for less than $50 accomplished what $2,000 anti-tank guns sometimes couldn’t. And that raised an uncomfortable question deep inside army doctrine. How did one untrained farm kid outperform our entire engineering corp? The engineering report.

The formal engineering analysis did not mince words. It listed the reasons for success in technical detail. Behavioral channeling traps placed where tanks would go, not where engineers wished they might. Visual deception camouflage designed from real soil, real rocks, real sun angles. Redundant kill paths shaped charge plans wire backups.

Psychological impact. German armor refused to attack terrain they previously considered safe. Garrett didn’t match German strength. He exploited German patterns. He didn’t design for what tanks could see. He designed for what tanks couldn’t. He didn’t try to build bigger weapons. He built smarter traps.

For the first time, formal U doctrine admitted something radical. unconventional civilian knowledge could outperform formal training. The manual 91 pages of farm logic. The army eventually produced a 91page manual titled improvised anti-tank obstacles and trap systems. Most of the core principles came straight from Garrett’s field notes written on scraps of note paper during the long nights before fed pass.

The manual taught soldiers to read terrain the way hunters read animal trails. Predict tank movements based on instinct, not order. Build traps from local materials. Prioritize invisibility over showmanship. Its most important paragraph came near the end. Effective battlefield engineering requires accepting that innovation does not always come from doctrine.

Soldiers with civilian experience may possess specialized insight more valuable than standardized procedures. It was the first time in army history that institutional doctrine confessed. Sometimes the farm boy knows something the engineers don’t. The German perspective. German prisoners later revealed how deeply the traps affected morale.

One panzer commander said, “Mines and guns we understood, but these invisible pits, no training prepared us for that. We feared the ground itself.” Another report noted, “American positions in confined terrain use anti-tank trap systems of unprecedented effectiveness. Losses exceed acceptable parameters. Recommend avoidance of mountain passes entirely.” Garrett hadn’t just killed tanks.

He had changed German behavior and fear did the rest. A force that refuses to advance is a force already defeated. The man behind the traps, Garrett served through Sicily, Italy, and France. He rose to staff sergeant, but he never became the kind of soldier who bragged.

When the war ended, he returned to South Dakota, ran the family ranch, and kept solving problems the same way he always had, quietly, logically, and with just enough improvisation to surprise everyone. In a 1992 interview, a historian pressed him. Why didn’t anyone else think of these traps? Garrett answered simply. Most people saw tanks as things you fight headon. I saw them the way I saw prairie dogs.

Predictable, habitual, vulnerable. If you knew where they stepped, he paused, then added, “You don’t need a big weapon if you understand behavior. That’s all it was.” They called his idea stupid. They called it a waste of time. They laughed at the dirt piles, the wooden lattice, the ridiculous notion that a farm boy could stop a tank with nothing but physics and instinct.

But in 11 seconds, the trap blew a panzer apart and forced everyone from sergeants to colonels to German armored commanders to rethink what was possible. Garrett didn’t win because he was stronger or better equipped or higher ranked. He won because he understood something armies often forget. Innovation doesn’t come from manuals.

It comes from people who see what others ignore. And if one farm kid could rewrite anti-tank warfare with scraps of wood and captured explosives, imagine what other forgotten stories are still out there.