February 26th, 1945. Dawn breaks over Eojima’s black volcanic beaches. Private Wilson Watson grips the 20 lb Browning automatic rifle, the gun every Marine dreaded carrying. Too heavy, too clunky, too slow for the lightning fast combat of the Pacific theater.

Military doctrine said automatic weapons belonged on fixed positions, not in the hands of advancing infantry. The Japanese had built their entire defense around this assumption. Lightweight machine guns, quick movements, hitand-run tactics that would overwhelm any marine foolish enough to lug a full auto rifle across open ground. But as Watson’s boots hit the sulfur stained sand, something the enemy never anticipated was about to unfold.

In 15 minutes on a blood soaked hilltop, this too heavy gun would prove that everything the military thought it knew about automatic weapons was dead wrong. One marine, 60 enemy troops, a weapon that wasn’t supposed to work. The Japanese had no idea what was coming. The Browning automatic rifle emerged from the mind of John Moses Browning in 1918, birthed in the final months of a war that ended before it could prove itself.

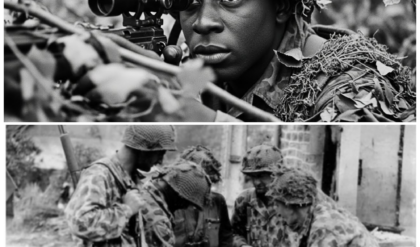

27 years later, as the Third Marine Division prepared for what would become the bloodiest battle in Marine Corps history, that same weapon sat heavy in the hands of men who questioned whether it belonged on a modern battlefield at all. Private Wilson Watson had carried the bar for 8 months through training camps from Paris Island to Camp Pendleton, and every step had reinforced what every Marine knew. The gun was a burden.

At 20 lbs fully loaded, it weighed twice as much as the standard M1 Garan. While Japanese troops moved through jungle and coral with their lightweight Namboo machine guns and Type 99 rifles, American riflemen struggled under the weight of a weapon that seemed designed for a different kind of war entirely.

The technical specifications told only part of the story. The bar fired the same 306 cartridge as the Garand, but at a cyclic rate of 500 to 650 rounds per minute in full automatic mode. Its effective range stretched to 600 yd. Impressive on paper, but the 20 round magazine emptied in less than 2 seconds of sustained fire.

Reload time under combat conditions averaged 8 to 12 seconds, an eternity when enemy fire was incoming. The weapon’s bipod legs, designed for stability, caught on everything from jungle vines to coral outcroppings. Most Marines removed them entirely, sacrificing accuracy for mobility. Watson had learned these limitations the hard way during months of training.

Born in rural Alabama, he understood machinery and precision in ways that many of his urban counterparts did not. His father had taught him to hunt with a Springfield bolt action, emphasizing patience and shot placement over volume of fire. The bar represented everything his upbringing had taught him to avoid waste, imprecision, reliance on machinery over skill.

Yet here he was, crouched in the pre-dawn darkness of February 26th, watching the silhouette of Ewima grow larger as their landing craft churned through Pacific swells. Intelligence reports had painted a picture of an island fortress unlike anything the Marines had encountered in 3 years of island hopping campaigns. The Japanese had abandoned their previous strategy of meeting amphibious assaults at the beach.

Instead, they had spent 8 months turning Ewoima’s 8 square miles into an underground maze of interconnected tunnels, bunkers, and firing positions. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Denig had briefed Watson’s battalion on the enemy’s defensive philosophy during their final planning session aboard the transport ship.

The Japanese commander, General Tatamichi Kuri Bayashi, had studied American amphibious tactics and concluded that traditional bonsai charges were suicide against superior American firepower. His 21,000 defenders would fight from prepared positions, forcing the Marines to dig them out one bunker at a time. Every hill, every ravine, every apparent piece of open ground had been pre-sighted for artillery and mortar fire. The tactical problem was unprecedented.

Previous Pacific battles had been won through rapid advances supported by naval gunfire and closeair support. Ewima’s defenders were buried too deep for naval shells to reach them effectively. The island’s volcanic terrain absorbed explosive force, turning massive bombardments into expensive displays that left the enemy largely intact. Victory would require infantry tactics, small units moving forward under fire, clearing positions with grenades, flamethrowers, and direct assault. Watson understood that his weapons reputation for poor battlefield performance stemmed from doctrinal

misuse rather than inherent flaws. Military planners had envisioned the bar as a squad support weapon, operated from fixed positions to provide covering fire for advancing riflemen. They had borrowed this concept from European warfare where machine gun nests dominated no man’s land and infantry advances occurred across relatively open terrain.

The Pacific theater demanded different thinking. Japanese positions were often separated by mere yards hidden in jungle or coral formations that required fighters to move constantly while maintaining sustained fire capability. As their landing craft approached the beach, Watson checked his ammunition load one final time. Standard doctrine called for the bar man to carry 12 20 round magazines, 240 rounds total.

The weight of ammunition alone approached 15 lb, added to the weapons 20 lb and his standard infantry kit. Other Marines in his squad carried eight round clips that weighed a fraction of his load. They could move quickly between positions, drop prone for accurate fire, and maneuver without the constant concern for ammunition conservation that governed every decision Watson made. The beach ahead looked deceptively quiet.

Naval bombardment had turned the black volcanic sand into a moonscape of craters and debris, but no enemy fire greeted the first waves of landing craft. Intelligence had predicted this. Kuribayashi’s strategy called for allowing the Marines to land in strength before triggering the defensive response.

Somewhere in the hills overlooking the beach, Japanese observers were counting boats and estimating American strength. The real battle would begin when the Marines moved inland. Watson’s squad leader, Sergeant McMahon, had spent the voyage studying aerial reconnaissance photographs of their objective. Hill 203 dominated the island’s southern approach, its slopes honeycombed with caves and bunkers that commanded fields of fire across the entire beach head.

Previous battles had taught the Marines that taking high ground was essential for establishing secure footholds, but Eoima’s defenders had turned that principle against them. Every hilltop was a fortress designed to channel American attacks into prepared killing zones.

The contradiction between doctrine and reality had become clear during training exercises in Hawaii. Squad tactics called for the bar man to establish a base of fire while riflemen advanced by bounds. But Pacific terrain rarely offered the clear fields of fire that made this tactic effective. More often, combat occurred at ranges measured in yards rather than hundreds of yards.

The enemy appeared suddenly from concealed positions, engaged briefly at close range, then disappeared into tunnel systems that connected defensive positions across the battlefield. Watson had begun to suspect that his weapons supposed weaknesses might become advantages under these conditions. The Bayer’s weight provided stability for rapid fire without the need for a bipod.

Its powerful cartridge retained effectiveness at close range, even when fired from unstable positions. Most importantly, its automatic fire capability could deliver overwhelming firepower during the brief moments when Japanese defenders exposed themselves. As the landing craft’s bow gate dropped and Watson stepped into the surf of Euoima, he carried more than just a controversial weapon.

He bore the weight of tactical assumptions that had governed American infantry doctrine since the First World War. Within hours, those assumptions would face their ultimate test against an enemy who had spent months preparing for exactly this moment. The too heavy gun that military planners had begun phasing out of infantry units was about to prove that sometimes the most criticized tools become the most decisive when wielded by someone who understood their true potential. The deception lasted exactly 47 minutes.

Watson’s boots had barely dried from the surf when the first mortar rounds began falling among the Marines scattered across the black sand. The enemy had waited with disciplined patience, allowing 4,000 Americans to bunch up on the narrow beach head before revealing the killing field they had prepared.

What followed was not a battle in any conventional sense, but a methodical destruction of men caught in an invisible web of interlocking fire. Watson’s platoon had advanced 300 yards inland when the hillsides erupted with muzzle flashes. Japanese positions that aerial reconnaissance had missed or dismissed as destroyed revealed themselves through curtains of fire that swept the volcanic terrain like deadly rain.

The Marines had walked into a trap designed by an enemy who understood their tactics better than they understood themselves. Every piece of cover the Americans sought had been pre-registered for mortar fire. Every route of advance channeled them toward machine gun positions hidden in caves and bunkers that naval bombardment could not reach. The sound was unlike anything Watson had experienced in training.

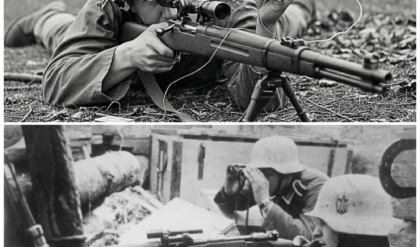

Japanese machine guns chattered with a distinctive rapid fire rhythm different from the slower, heavier beat of American weapons. The Namboo Type 92 fired 7.7 mm rounds at a cyclic rate of 450 rounds per minute, creating a sustained buzz that mixed with the crack of rifle fire and the deeper thump of mortars. But it was the silence between bursts that proved most terrifying moments when Marines realized that movement meant death and stillness meant eventual death from indirect fire.

Sergeant McMahon’s voice cut through the chaos, directing his squad toward a depression in the volcanic rock that offered momentary shelter. Watson followed, the bar’s weight shifting awkwardly as he scrambled across terrain that seemed designed to punish anyone carrying more than basic equipment.

Around him, Marines with lighter weapons moved more quickly, diving for cover that often proved elusory when enemy fire came from unexpected angles. The Japanese had positioned their weapons to create crossfires that eliminated dead space and forced attackers into increasingly desperate situations. The tactical problem became clear within minutes of the ambush.

Traditional squad tactics relied on establishing a base of fire to suppress enemy positions while other elements maneuvered for assault. But the enemy remained invisible, firing from positions that could not be identified until they revealed themselves through muzzle flashes. When Marines attempted to return fire, they exposed themselves to observers who directed mortar fire with lethal precision. The result was a deadly game of hideand-sek where the Japanese held every advantage.

Watson’s first engagement lasted less than 30 seconds, but taught him everything he needed to know about his weapons potential. A Japanese machine gun position opened fire from a cave mouth approximately 60 yards to his front, its tracers seeking targets among the scattered marines.

Following doctrine, Watson deployed the bar’s bipod and attempted to return precise fire from a prone position. The weapon’s accuracy was excellent, but his position immediately drew attention from enemy mortars. Three rounds landed within 20 yards of his location, forcing him to abandon his carefully prepared firing position and seek new cover.

The lesson was immediate and brutal. The bar’s conventional role as a squad support weapon was not only ineffective, but potentially suicidal against an enemy who had spent months preparing for exactly these tactics. Watson realized that his weapon supposed disadvantages, its weight, its requirement for close-range engagement, its ammunition consumption were actually adaptations to a different kind of warfare than what military planners had envisioned.

Private McMahon, crouched 10 yards to Watson’s left, had exhausted two eight round clips from his Garand trying to locate the machine gun position. His accurate rifle fire, devastating at longer ranges, proved inadequate against an enemy who appeared briefly before disappearing into prepared positions.

The Japanese had learned to minimize their exposure time, firing short bursts before withdrawing into tunnels that connected their defensive positions. conventional marksmanship skills, the foundation of marine training, became less relevant when targets appeared for seconds at a time. The breakthrough came when Watson abandoned doctrinal thinking and began treating his weapon as a close assault tool rather than a support weapon.

When the Japanese machine gun resumed firing, Watson left his covered position and began moving directly toward the enemy. The bar’s 20 lb weight, previously a hindrance, now provided stability for accurate fire while advancing. Its automatic capability allowed him to maintain suppressive fire without the pause required for bolt manipulation.

Most importantly, its powerful 300 6 cartridge retained lethal effectiveness at the close ranges where Pacific combat actually occurred. Watson’s advance covered 40 yards in less than 20 seconds. the bar firing in controlled bursts that kept the enemy position suppressed while he closed distance.

The Japanese crew trained to engage targets at longer ranges found themselves facing sustained automatic fire from an increasingly close opponent. Their tactical doctrine had not anticipated an enemy who would advance directly into their field of fire while maintaining effective return fire. When Watson reached effective range approximately 20 yards from the cave mouth, he emptied an entire magazine into the position in one sustained burst.

The psychological impact on nearby Marines was immediate. They had witnessed one man with an automatic weapon neutralize a position that had pinned down an entire squad. More importantly, they had seen a tactical approach that matched the reality of Pacific combat rather than the theories developed in peaceime training.

The bar dismissed as two cumbersome for mobile warfare had proven decisive when employed aggressively at close range. But Watson’s success came at a cost that illustrated the weapon’s fundamental challenge. His 20 round magazine emptied in one engagement represented more than 8% of his total ammunition load.

Conventional rifle fire allowed for precise ammunition conservation with each shot carefully aimed and accounted for. Automatic fire demanded a different calculation, trading ammunition efficiency for tactical speed and psychological effect. Watson understood that his remaining magazines would need to count, not just in terms of targets engaged, but in terms of battles that could be won or lost based on sustained fire capability.

The platoon’s advance resumed, but the landscape had changed fundamentally. Marines who had previously sought long range firing positions now moved aggressively toward enemy positions using terrain features for concealment rather than establishing static defensive lines.

Watson’s demonstration had revealed that Japanese defensive tactics were vulnerable to direct assault by determined attackers who could maintain fire while advancing. The key was abandoning the conventional wisdom that automatic weapons required fixed positions to be effective. As the platoon approached the base of Hill 203, Watson counted his remaining ammunition. 10 magazines, 200 rounds total. The mathematics of automatic fire were unforgiving.

At his demonstrated rate of consumption, he possessed perhaps 10 more engagements before becoming simply another rifleman. But he had learned something that would prove more valuable than ammunition conservation. The Japanese had prepared for a conventional American assault, not for Marines who understood that their most criticized weapon might be their most effective tool when used without regard for peacetime doctrine.

The mortar round that changed everything landed 23 yards behind Watson’s position at 11:47 on the morning of February 27th. The explosion killed Corporal Henderson instantly and wounded two other Marines badly enough to remove them from the fight. More critically, it severed the communication wire that connected Watson’s platoon to battalion headquarters, leaving 32 Marines isolated on a hilltop that Japanese artillery had already registered for destruction.

Watson found himself alone, not by choice, but by circumstance. The mortar barrage that followed Henderson’s death scattered his squad across a 100 yards of broken terrain, each marine seeking whatever shelter the volcanic rock could provide. When the shelling stopped, an eerie quiet settled over the hill.

The kind of silence that preceded either retreat or annihilation. Through the sulfur tinged air, Watson could see Japanese infantry moving through positions that should have been cleared hours earlier, reoccupying bunkers and cave mouths that connected to the tunnel system, honeycombing the island’s interior.

The tactical situation was worse than desperate. Watson’s platoon had advanced beyond supporting distance from other Marine units, drawn forward by what they had believed was a breakthrough in Japanese defenses. Instead, they had walked into a carefully planned trap.

The enemy had allowed them to take the hills crest, then sealed off their retreat routes with coordinated fire from positions that had remained hidden during the initial assault. Now those same positions were revealing themselves. Confident that isolated Marines posed no significant threat to their defensive network. Watson counted seven distinct enemy positions within his field of view.

Each one carefully cited to provide mutual support for the others. Japanese doctrine emphasized interlocking fields of fire that eliminated dead space and forced attackers into prepared killing zones. The positions were connected by tunnels that allowed defenders to reinforce threatened points or withdraw when under direct assault only to reappear elsewhere in the network.

Traditional marine tactics based on identifying and destroying individual positions proved inadequate against an enemy who could disappear and reemerge at will. The first Japanese soldiers to approach Watson’s position moved with the confidence of men who believed they faced a defeated enemy. A squad of eight soldiers emerged from a tunnel entrance 40 yards down the slope.

Their Type 99 rifles held at the ready, but not aimed with the urgency that combat demanded. They had been told that the Americans on the hilltop were cut off and demoralized, waiting for either rescue or death. What they encountered instead was a Marine who had spent two days learning that conventional tactics were not merely inadequate, but actively harmful in this new kind of warfare.

Watson’s opening burst caught the Japanese squad completely exposed in open ground. The Bay’s sustained fire swept across their formation like a scythe. The powerful 306 rounds proving devastatingly effective at close range. Eight enemy soldiers fell in less than 5 seconds. Their bodies scattered across terrain that moments before had seemed secure.

But Watson understood that this initial success was merely the beginning of a much larger engagement. The Japanese had not committed a single squad to retaking the hilltop. They had committed an entire company, more than 120 soldiers who could afford to accept casualties that would destroy a smaller force.

The psychological impact of Watson’s fire was as important as its physical effects. Japanese soldiers, who had been moving confidently toward what they believed was a routine mopping up operation, suddenly found themselves under sustained automatic fire from an enemy who should have been suppressed or eliminated.

Their tactical doctrine had not prepared them for a single marine who could maintain effective fire while constantly changing position. More critically, their officers had not anticipated an opponent who understood that mobility and aggression could overcome prepared defensive positions. Watson’s next engagement occurred less than 2 minutes later when a second squad attempted to flank his position from the north.

This time the enemy approached with greater caution, using volcanic outcroppings for cover and advancing by bounds. Their tactics were sound by conventional standards, but they had not adapted to facing an automatic weapon employed aggressively rather than defensively.

Watson waited until the lead elements were committed to their assault, then moved directly toward them while firing sustained bursts that forced them into cover. The key to Watson’s success lay in his abandonment of static defensive thinking. Instead of establishing a firing position and attempting to hold it against superior numbers, he treated the entire hilltop as a mobile battlefield where movement and fire were integrated into a single tactical concept.

The bar’s weight, previously a liability, now provided the stability necessary for accurate fire while advancing. Its automatic capability allowed him to maintain suppression without the pause required for bolt manipulation that characterized conventional rifles. Japanese return fire intensified as more enemy soldiers realized they faced a significant threat rather than isolated survivors.

Rifle rounds and grenade fragments chipped volcanic rock around Watson’s position, forcing him to time his movements carefully to avoid concentrated fire. But the enemy’s response revealed a critical weakness in their tactical approach. They were attempting to engage a mobile target using techniques designed for static warfare.

Their positions, while mutually supporting against conventional assault, became liabilities when facing an opponent who refused to remain in one location long enough to be effectively targeted. Watson’s ammunition consumption during the first 10 minutes of sustained combat was enormous by conventional standards.

He had expended four 20 round magazines, 80 rounds that represented more than onethird of his total load. But these calculations ignored the tactical value of sustained automatic fire against an enemy trained to expect aimed shots from bolt-action rifles. Each burst not only engaged visible targets, but forced others to seek cover, disrupted their coordination, and created opportunities for further advances that would have been impossible under conventional rifle fire.

The turning point came when Watson realized that Japanese defensive positions were actually more vulnerable to close assault than to long range engagement. Cave mouths and tunnel entrances that provided excellent protection against distant rifle fire became death traps when approached by an enemy with automatic weapons.

The 306 cartridge retained lethal effectiveness even after ricocheting off volcanic rock, creating a cone of deadly fragments that reached into positions where direct fire could not penetrate. Watson’s assault on the central bunker complex began at 12:05 and lasted exactly 4 minutes. Moving from position to position while maintaining continuous fire, he advanced across 60 yards of open ground that should have been impassible under enemy observation.

His success depended not on superior marksmanship or tactical brilliance, but on his understanding that the bar was fundamentally different from every other weapon on the battlefield. It was not a rifle that happened to fire automatically, but an automatic weapon that could be employed with rifle-like precision when necessary.

The bunker that had anchored Japanese defenses on the hill contained 12 enemy soldiers and enough ammunition to sustain defensive fire for hours. Watson’s approach eliminated that position in less than 30 seconds of sustained automatic fire. The bar’s devastating close-range effectiveness proving overwhelming against defenders who had prepared for a different kind of assault.

When silence returned to the hilltop, Watson found himself surrounded by the results of 15 minutes that had redefined what one Marine with the right weapon could accomplish against impossible odds. The ammunition count told its own story. Watson had fired 160 rounds, leaving him with 80 rounds for whatever came next. But the tactical landscape had changed completely.

Japanese positions that had seemed impregnable minutes earlier lay silent. Their defenders either dead or withdrawn through tunnel systems that no longer provided the sanctuary they had once offered. The too heavy gun had proven that mobility and firepower, properly combined, could overcome any defensive position that depended on conventional tactical assumptions. The bullet that found Watson struck him in the left shoulder at 12:21, a 7.

7 mm round from a Japanese sniper who had been watching the hilltop through a scope for the better part of an hour. The impact spun Watson around and dropped him behind a cluster of volcanic rocks that had provided his last firing position.

Blood soaked through his utility jacket, warm against skin that had grown cold from shock and adrenaline. For 30 seconds, the only sounds on the hill were his own labored breathing and the distant crack of rifle fire from other parts of the battlefield. The sniper’s bullet should have ended Watson’s fight, but it had struck at an angle that sent it through muscle and senue without hitting bone or major arteries.

Watson discovered this through careful inventory of his body’s responses rather than any formal medical training. He could still move his arm, though each motion sent lightning through his nervous system. More importantly, he could still operate the bar’s controls, even if reloading would require adaptations to accommodate his wounded shoulder.

The weapon itself had survived the fall undamaged, its robust construction proving as reliable as its reputation suggested. Japanese voices echoed from positions down the slope, discussing tactical options in tones that suggested confidence rather than desperation.

They had witnessed Watson’s assault on their defensive positions and understood that they faced an exceptional opponent, but they also knew that wounded men had limitations that could be exploited through patient tactics. The sniper had done his job by wounding rather than killing. A wounded marine might attempt to hold his position, creating opportunities for coordinated assault that a dead enemy could not provide.

Watson’s ammunition situation had become critical in ways that extended beyond simple round counts. He possessed exactly 60 cartridges and three magazines, enough for perhaps 3 minutes of sustained combat at his previous rate of consumption.

But more significantly, his wounded shoulder would prevent the rapid magazine changes that automatic fire demanded. Each reload would require 15 to 20 seconds rather than the 8 seconds he had managed when unwounded. In a close-range firefight against multiple opponents, those additional seconds could prove fatal. The tactical problem facing Watson was unlike anything covered in Marine Corps training manuals.

Military doctrine assumed that wounded personnel would be evacuated or would seek defensive positions until medical aid arrived. Neither option existed on his isolated hilltop. Evacuation required communication with supporting units, which had been severed by mortar fire hours earlier.

Defensive positions required mutual support from other Marines who had been scattered across terrain that made coordination impossible. Watson faced the choice between retreat and continued aggression with either option carrying nearly certain consequences. The decision was made for him when Japanese infantry began moving up the slope in coordinated bounds.

Their approach suggesting a platoon strength assault designed to overwhelm his position through concentrated fire and maneuver. Watson counted at least 20 soldiers in the initial wave with more following through terrain features that concealed their actual numbers. They moved with the disciplined patience of troops who understood that time favored their cause.

A wounded enemy with limited ammunition could not sustain defensive fire indefinitely. Watson’s response violated every principle of defensive warfare taught in military schools. Instead of seeking cover and attempting to establish interlocking fields of fire, he moved toward the advancing enemy while firing controlled bursts that forced them to ground.

His wounded shoulder created an awkward firing stance that actually improved his accuracy by limiting his tendency to spray rounds across wide target areas. Each burst was more carefully aimed than his previous automatic fire with devastating results against enemy soldiers who had not expected aggressive action from a wounded opponent. The Japanese assault faltered within minutes as soldiers trained for conventional tactics found themselves facing an enemy who refused to behave according to established patterns. Their doctrine called for suppressing defensive positions with concentrated fire while assault elements

maneuvered for close combat. But Watson’s position changed constantly, making suppression impossible and rendering their carefully rehearsed assault techniques useless. More critically, his automatic fire created casualty rates that exceeded what their tactical planning had anticipated.

Watson’s wound became a tactical advantage in unexpected ways. The pain forced him to move more deliberately, eliminating the rush decisions that had characterized his earlier engagements. Each position change was calculated to maximize cover while maintaining fields of fire that covered likely enemy approaches.

His reduced physical capacity required more efficient use of ammunition, leading to shot placement that was actually more effective than his previous sustained bursts. The limitation became liberation from wasteful tactics he had not realized he was employing. The second wound came at 1238 when a grenade fragment opened a gash along Watson’s left leg.

The explosion had been intended to flush him from cover, but instead provided confirmation that the enemy knew his general location while remaining uncertain about his exact position. Watson used this knowledge to create deception, firing from one location, then immediately moving to another before return fire could be effectively directed.

His blood trail, visible on the dark volcanic rock, actually assisted this deception by suggesting wounds more severe than reality. Japanese casualties mounted steadily as their assault continued. Watson’s accurate fire had eliminated at least 15 enemy soldiers, reducing their numerical advantage while creating psychological pressure that affected tactical decisions.

Officers who had planned a methodical reduction of his position found themselves committing reserves to maintain assault momentum. The result was escalating commitment that transformed a routine operation into a desperate struggle for control of terrain that held no strategic value beyond the symbolism of defeating one American marine. The critical moment arrived when Watson’s ammunition reached its final magazine.

20 rounds represented perhaps 90 seconds of combat capability, after which he would become simply another wounded marine awaiting either rescue or death. But those 20 rounds also represented the culmination of everything he had learned about employing automatic weapons in close combat.

Each cartridge would be fired with the precision of a sniper combined with the tactical mobility that had made his previous actions successful. The Japanese commander’s final assault committed every available soldier to simultaneous attack from multiple directions. Watson counted 37 enemy troops converging on his position, their coordination suggesting excellent training and leadership.

Under conventional circumstances, such numbers would guarantee tactical success against a single wounded defender. But these were not conventional circumstances, and Watson was no longer fighting as a conventional marine. He was fighting as a man who understood that his weapon’s true potential could only be realized when employed without regard for doctrinal limitations.

Watson’s last stand lasted exactly 3 minutes and 17 seconds, moving constantly while firing controlled bursts, he engaged targets that appeared briefly before disappearing into the volcanic terrain. His wounded condition forced economy of motion that actually improved his effectiveness.

Each shot carefully planned and executed with precision that his earlier automatic fire had lacked. When his final round was expended at 12:44, the hilltop held only silence and the evidence of what one Marine with the right weapon could accomplish when pushed beyond every limitation the training had imposed.

The battlefield assessment conducted hours later by advancing Marine units would record 60 Japanese casualties in the immediate area around Watson’s position. The count included soldiers who had been wounded and withdrawn through tunnel systems, making exact numbers impossible to determine. What could be measured precisely was the tactical impact. An entire company of experienced Japanese infantry had been neutralized by a single wounded marine whose weapon was considered obsolete by military planners who had never faced the reality of close-range automatic fire employed aggressively rather than defensively. The stretcherbears who reached Watson at 1435 found him conscious but barely

coherent. His blood loss severe enough to require immediate evacuation to the hospital ship offshore. His left shoulder had been shattered by the sniper bullet, requiring surgery that would take place under conditions far removed from the sterile operating rooms of stateside hospitals.

The grenade fragment in his leg had severed muscle tissue, but missed major arteries, a piece of fortune that probably saved his life during the 3 hours he had held the hilltop alone. Lieutenant Colonel Denig arrived at the aid station 20 minutes after Watson’s evacuation, carrying field reports that painted an incomplete picture of what had occurred on Hill 203.

Radio communications had been severed for most of the engagement, leaving battalion headquarters to piece together events from the testimony of scattered Marines who had witnessed portions of the action from distant positions. The physical evidence spoke more clearly than witness statements.

60 confirmed Japanese casualties in an area roughly 100yd square with weapons and equipment suggesting that an entire company had been committed to the assault. The Browning automatic rifle lay. Watson had dropped it, its barrel still warm despite the hours that had passed since his final shots.

Ordinance specialists who examined the weapon found it mechanically perfect with no signs of the overheating or mechanical failure that automatic weapons were expected to suffer during sustained combat. The barrel showed normal wear patterns. The action cycled smoothly, and the magazine well retained the precise tolerances that allowed reliable feeding under combat conditions.

Most significantly, the weapon showed no evidence of the modifications or field expedience that Marines typically employed to improve reliability in Pacific conditions. Watson’s ammunition expenditure became the subject of detailed analysis by Marine Corps intelligence officers seeking to understand how conventional smallarms doctrine had proven so inadequate against Japanese defensive tactics.

Field counts suggested that Watson had fired approximately 200 rounds during his 15minute engagement, representing nearly 90% of his total load. By conventional standards, such consumption rates were unsustainable and tactically irresponsible. By the standards Watson had established, they represented the minimum firepower necessary to neutralize a well-prepared enemy position through aggressive assault rather than methodical reduction.

The tactical implications extended far beyond a single engagement on a volcanic island in the Pacific. Marine Corps planners had based their small arms doctrine on European experience where automatic weapons were employed primarily in defensive roles or as support weapons for advancing infantry.

Watson had demonstrated that the same weapons could be decisive when employed aggressively at close range, but only when operators abandoned conventional thinking about ammunition conservation and positional stability. The lesson was simple in concept but revolutionary in practice. Automatic weapons reached their full potential only when used without regard for peaceime limitations.

Captain Morrison, the battalion intelligence officer, spent three days interviewing Marines who had observed portions of Watson’s action from supporting positions. Their accounts described a style of combat that bore little resemblance to approved Marine Corps tactics, but proved devastatingly effective against an enemy prepared for conventional assault.

Morrison’s report filed on March 2nd recommended fundamental changes in how automatic weapons were employed by Marine infantry with particular emphasis on close-range tactics that maximized firepower at the expense of ammunition conservation. The medical report on Watson’s condition revealed wounds that should have been fatal under conventional combat circumstances.

His shoulder injury had severed muscles necessary for accurate rifle fire, while his leg wound had reduced his mobility to the point where normal tactical movement became impossible. Yet, he had continued fighting for more than three. Hours after receiving these wounds, adapting his tactics to accommodate physical limitations that would have rendered most Marines combat ineffective.

The adaptation had actually improved his tactical effectiveness by forcing more deliberate shot placement and more efficient use of available cover. Watson’s evacuation to the hospital ship offshore took place during continuing combat operations that would consume another month before Euima was declared secure.

His individual action represented less than 1% of the total casualties inflicted during the battle. Yet his tactical innovations influenced Marine Corps doctrine for the remainder of the Pacific War. Units equipped with Browning automatic rifles began employing them aggressively rather than defensively with results that vindicated Watson’s instinctive understanding of the weapon’s true capabilities.

The Medal of Honor recommendation prepared by Lieutenant Colonel Denig on March 5th described Watson’s actions in language that emphasized courage and determination while understating the tactical innovations that had made his success possible. Military decorations traditionally recognize bravery rather than tactical brilliance, leaving the doctrinal implications of Watson’s performance to be addressed through separate channels.

The citation credited him with single-handedly neutralizing an enemy company language that was factually accurate, but failed to convey the broader significance of his tactical approach. Watson’s recovery aboard the hospital ship took six weeks, during which time he remained largely unaware of the analytical attention his action had generated within Marine Corps headquarters.

His primary concern was physical rehabilitation that would allow him to return to his unit, though medical officers had already determined that his wounds would require evacuation to stateside hospitals. The war would continue without him. But his contribution would influence how it was fought by thousands of Marines who would never know his name.

The Browning automatic rifle’s reputation within the Marine Corps underwent fundamental revision during the final year of the Pacific War. Weapons previously considered too heavy for aggressive infantry tactics were redistributed to Marines trained in the close assault techniques that Watson had developed through desperate improvisation.

Training programs began emphasizing mobility and firepower over the positional tactics that had dominated pre-war doctrine. Most importantly, ammunition allocation for automatic weapons was increased to reflect the reality that sustained fire capability was more valuable than conservation in close-range combat.

The Pacific theat’s unique tactical requirements had created conditions where conventional military wisdom proved inadequate, forcing individual Marines to develop solutions that contradicted established doctrine. Watson’s success represented the intersection of desperate circumstances, innovative thinking, and a weapon system that had never been employed according to its true capabilities.

His 15 minutes on Hill 203 demonstrated that the most criticized equipment could become the most decisive when used by someone who understood that survival required abandoning preconceptions about how warfare was supposed to be conducted. The final irony of Watson’s story lay in the timing of his tactical breakthrough.

By March 1945, military planners had already begun phasing out the Browning automatic rifle in favor of lighter, more conventional weapons that reflected peacetime assumptions about infantry combat. Watson had proven the weapon’s effectiveness just as the military establishment had decided it was obsolete, leaving future generations of soldiers to rediscover tactical principles that one wounded Marine had learned through desperate necessity on a hilltop in the Pacific.

The too heavy gun that had saved his life would soon disappear from American arsenals. Its true potential realized too late to influence the doctrinal changes that might have saved thousands of other lives in the brutal island campaigns that defined the Pacific Four.