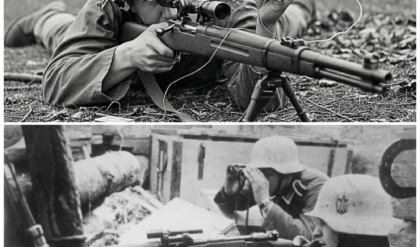

On the morning of October 23rd, 1942, at the mouth of the Matanakau River on Guadal Canal, a marine heavy machine gun section crowded around a captured Japanese type 95 Hgo tank, measuring tape in hand. The front hull and turret plating read 12 mm thick. The roof and rear armor measured as little as 6 to 9 mm.

Inside the cramped fighting compartment, they found a one-man turret with no radio, just colored flags and hand signal cards scattered across the commander’s seat. Staff Sergeant Mike Torres from Second Battalion ran the numbers in his head while his gunner traced the armor measurements with a grease pencil.

Their Browning M2 heavy machine gun fired armor-piercing incendiary rounds specified to completely perforate 7/8 in of steel plate at 100 yards. 7/8 in equal roughly 22 mm. The HGO’s thickest armor was 12 mm. At the ranges, Pacific firefights collapsed to 50 to 150 yards. The math was simple and brutal.

Torres looked at his assistant gunner and said what every Marine heavy weapons man was starting to realize. This wasn’t armor. It was a tin can on tracks. The Japanese had been using these 7 and 1/2 ton light tanks to terrorize green American troops for months, appearing through jungle darkness like iron monsters, their 37 mm guns and twin machine guns cutting down entire squads before vanishing into the green.

But the numbers didn’t lie, and neither did the measuring tape. When Torres’s battalion commander heard the armor thickness report, he gathered his heavy machine gun section leaders around a sand table that evening and asked one simple question. If a 50 caliber armor-piercing round could punch through 22 mm of steel, and these Japanese tanks only had 12 mm of protection, what exactly were his marines afraid of? But there was something the armor measurements couldn’t tell them.

something that would turn those laughing Marines into the most feared tank hunters in the Pacific. The captured Hoggo sat in the motorpool like evidence in a court case, its olive drab paint chipped and scorched from the fighting near Point Cruz. Colonel David Shupe walked the perimeter of the tank with his battalion commanders, listening as gunnery sergeant Pete Kowalsski read from his inspection notes.

The armor thickness measurements had been confirmed three times using different calipers and measuring devices. Front glacus plate 12 mm, turret face 12 mm, side hole plating 9 mm, rear engine deck 6 mm in places. The roof armor over the engine compartment was so thin that Kowalsski had punched a screwdriver through it with moderate pressure, leaving a clean hole that looked like it had been drilled. Shupe studied the interior through the open hatches.

The fighting compartment was barely large enough for three men with the commander’s position crammed into a turret so narrow that the man inside would have to serve as gunner, loader, and radio operator simultaneously. Except most of these tanks carried no radio at all.

Instead, the commander’s position held a canvas pouch filled with colored signal flags and a set of hand signal charts printed on rice paper. Communication between tanks would happen through flag signals or by physically running messages between vehicles. In the chaos of combat, with smoke and muzzle flashes and Marines shooting back, coordinating multiple tanks would be nearly impossible.

The 37mm gun looked substantial until the Marines examined its ammunition storage. The armor-piercing rounds were adequate for fighting other light tanks. But against American Shermans or even the Marine Corps’s 37mm anti-tank guns, the Hugo would be outgunned and outranged. The tanks two machine guns used the same 7.7 mm cartridge as Japanese infantry rifles, effective against personnel, but hardly devastating against dugin positions.

Everything about the vehicle suggested it had been designed for infantry support against lightly defended positions, not tank versus tank combat or breakthrough operations against prepared defenses. But it was the armor specifications that changed how the Marines looked at Japanese mechanized attacks.

Technical Sergeant Ray Morrison, who had worked in a Detroit automotive plant before the war, ran his hands along the hole plating and explained what the numbers meant in practical terms. American 50 caliber armor-piercing incendiary rounds designated API M8 were designed to completely penetrate 7/8 in of homogeneous steel armor at 100 yd. 7/8 in converted to roughly 22 mm.

The HGO’s thickest armor measured 12 mm with most of the hull and turret plating running between 6 and 9 mm thick. At the ranges where Pacific combat typically occurred, 50 to 150 yards in jungle terrain, the 50 caliber round would not just penetrate the Japanese armor, it would punch through cleanly and continue traveling with enough energy to cause catastrophic damage inside the fighting compartment.

Morrison sketched the ballistics on a piece of cardboard, showing how the steel core API round would behave against different thickness of armor plate. Against 6mm plating, the kind found on the HGO’s rear deck and roof, the 50 caliber round would penetrate at ranges approaching 400 yd. Against the 12 mm frontal armor, penetration was guaranteed at any range under 200 yd and probable at distances up to 300 yd.

The side armor, measuring 9 mm in most places, offered no real protection at combat ranges. A heavy machine gun positioned to fire across the long axis of an attacking tank could potentially hold the vehicle from bow to stern with sustained fire. The tactical implications rippled through the battalion staff meeting that evening.

If Japanese light tanks could be penetrated by 50 caliber fire, then every Marine heavy machine gun section became a potential anti-tank unit. The M2 Browning was already positioned throughout marine defensive lines for anti-personnel and anti-aircraft work. The same weapons loaded with armor-piercing ammunition and fired from stable positions could engage Japanese armor directly rather than waiting for dedicated anti-tank guns or bazookas to arrive.

The Marines had been treating Hoggo appearances as armor threats requiring specialized responses, but the thickness measurements suggested these vehicles were more vulnerable than a typical Japanese pillbox. Captain Willie Jones, commanding First Battalion’s heavy weapons company, gathered his machine gun section leaders to discuss engagement techniques.

The armor-piercing incendiary rounds would be most effective when fired in short aimed bursts at specific target areas. Vision ports and periscope mounts represented weak points where even near misses could blind the crew or destroy optical equipment. The turret ring, where the rotating turret met the hull, offered a thin seam that might be vulnerable to precisely aimed fire. Engine louvers and cooling vents on the rear deck could be targeted to disable the vehicle’s mobility or start fires in the engine compartment. Most importantly, the tank’s thin armor made it vulnerable to spalling. fragments of

steel blown off the interior surface of the armor plate when a round struck from outside. Even if a 50 caliber round failed to achieve complete penetration, the impact could send steel fragments ricocheting through the crew compartment at high velocity, wounding or killing the men inside.

With armor as thin as the HGO carried, spalling would occur with almost any solid hit from armor-piercing ammunition. The Marines began to understand that Japanese tank tactics reflected the vehicle’s limitations rather than their strengths. HGO attacks typically came at night or dawn when visibility was poor and the tanks could approach to close range before being spotted.

The vehicles moved in small groups, rarely more than three or four at a time, suggesting that coordination between multiple tanks was difficult without radio communication. Infantry typically rode on the tanks or advanced alongside them, using the vehicles more as mobile pillboxes than breakthrough weapons.

When Marines had encountered these tactics previously, the combination of darkness, surprise, and the psychological effect of armor had often been enough to disrupt offensive positions before the Americans could organize effective resistance. But now the numbers told a different story. 7 and 12 tons of steel and three Japanese crewmen represented a target, not a threat.

The Hugo’s thin armor made it vulnerable to weapons the Marines already carried and positioned throughout their lines. Its limited communications made coordinated attacks difficult to sustain once the initial surprise was lost. The crew of three, crammed into a vehicle barely larger than a pickup truck, would be vulnerable to spalling and penetration from multiple directions once Marines began firing armor-piercing rounds from established positions.

As Shupe walked away from the captured tank that evening, he knew that the next time Japanese armor appeared in front of Marine positions, his men would be ready with a very different response than retreat or panic. They would be ready with mathematics measured in millimeters of steel plate and the muzzle velocity of 50 caliber ammunition traveling at 2800 ft per second.

The attack came at dusk on October 23rd, 1942, exactly as Colonel Shup’s intelligence section had predicted. Two battalions of Japanese infantry emerged from the jungle west of the Matanika Rivermouth, moving in disciplined columns toward the sandbar crossing. Behind them, the distinct rumble of tank engines announced the arrival of nine type 95 HGO tanks from the first independent tank company.

Their crews following the tactical manual that called for coordinated armor infantry assaults at the boundary between day and night when American visibility would be compromised. But Japanese forces could still navigate by terrain features. Lieutenant Colonel Lewis Puller, commanding First Battalion, Third Marines, watched the approach through binoculars from his command post on the eastern riverbank.

The Japanese formation moved with precision that spoke of careful rehearsal. Infantry squads had positioned themselves to ride on the tank holes and turrets, using the vehicles as mobile cover while advancing across the exposed sandbar. Additional rifle companies moved in bounds behind the armor, ready to exploit any breakthrough the tanks achieved.

The attack represented exactly the kind of coordinated mechanized assault that had broken Chinese and British positions throughout the early war, combining the shock effect of armor with the firepower of veteran infantry. But Puller’s Marines had spent the previous 3 weeks preparing for precisely this scenario.

437mm M3 anti-tank guns had been pre-sighted to cover the Sandbar crossing, their crews having ranged the exact distances during daylight and marked aiming stakes for night firing. Artillery forward observers had registered concentrations on the approach routes with four battalions of Marine howitzers loaded and ready to fire on call.

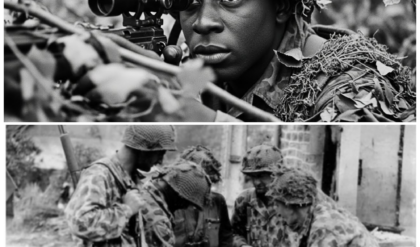

Most significantly, heavy machine gun sections had been positioned to deliver interlocking fire across the sandbar. Their Browning M2 weapons loaded with armor-piercing incendiary ammunition and trained on the narrow crossing points where the Japanese armor would be forced to funnel. The engagement opened when the lead Hugo reached OS. the western edge of the sandbar. Staff Sergeant Mike Torres, commanding the second battalion’s primary machine gun section, opened fire at a range of 180 yards with short bursts aimed at the tank’s frontal armor.

The API round struck with visible flashes as the incendiary compound ignited on impact, and Torres could see spalls of steel being blown off the interior surface of the armor plating. The Japanese tank continued forward, but its movement became erratic as the crew struggled with the effects of spalling and the shock of repeated impacts against their thin protective shell.

Within seconds, all four Marine machine gun sections were engaging targets across the sandbar. The interlocking fire created a web of armor-piercing tracers that swept the Japanese infantry off the tank holes before the riders could return effective fire. Sergeant Ray Morrison, firing from a prepared position on the north flank, concentrated on the vision ports and periscope mounts of the second HGO, systematically destroying the crew’s ability to see and navigate.

His sustained bursts walked across the turret face and hull front. Each impact sending fragments of steel ricocheting through the crew compartment. The 37mm anti-tank guns engaged as the Japanese tanks reached the center of the sandbar crossing. Gunner Corporal Jim Walsh, firing from a concealed position behind a coral embankment, hit the lead HGO with three armor-piercing rounds in rapid succession.

The first round penetrated the turret ring and jammed the rotating mechanism. The second struck the whole front and penetrated completely, killing the driver and setting fire to ammunition stored in the forward compartment. The third round hit the engine deck and disabled the vehicle’s mobility, leaving it motionless in the middle of the crossing, where it became a reference point for artillery observers. The Japanese attack began to unravel as the lead vehicles were stopped or damaged.

Without radio communication between tanks, the trailing HOS could not coordinate their movement or respond effectively to the changing tactical situation. Some crews attempted to reverse and find alternate crossing points, but the Marine machine gunners followed their movement with sustained fire that prevented the infantry from remounting and supporting the armor.

Other tanks continued forward into the killing zone, where concentrated fire from multiple directions overwhelmed their thin armor protection and small crews. Artillery began falling on the western approaches at 2115 hours as marine forward observers called in pre-registered concentrations on the Japanese assembly areas.

The howitzer fire disrupted the infantry formations trying to support the tank attack and prevented fresh troops from moving forward to reinforce the assault. Simultaneously, the artillery created a curtain of explosions that isolated the tanks already committed to the crossing from there, supporting elements, leaving them to fight independently against prepared marine positions. By 2230 hours, six of the nine Japanese tanks had been knocked out or abandoned on the sandbar.

The remaining three vehicles attempted to withdraw, but Marine machine gunners maintained harassing fire that prevented their crews from effectively operating the tanks or coordinating with surviving infantry. One Hago threw a track while attempting to navigate around a destroyed vehicle and was subsequently hit by multiple 37mm rounds that penetrated the thin rear armor and ignited the fuel tanks.

Another tank made it halfway back to the Western Bank before sustained 50 caliber fire through the engine compartment caused a catastrophic mechanical failure that left the vehicle immobilized and burning. The final Japanese tank reached the jungle edge, but was abandoned by its crew after taking multiple penetrating hits from armor-piercing ammunition.

Marine patrols found the vehicle the following morning with 17 holes punched through various sections of the hull and turret, each representing a 50 caliber round that had completely penetrated the 6 to 12 mm armor plating. Blood stains on the interior walls and floor showed where spalling fragments had wounded or killed the crew members, forcing them to abandon their vehicle despite its continued mechanical operation.

When the attack ended at 0115 hours on October 24th, all nine Japanese tanks lay wrecked on the sandbar or abandoned on the approaches. Post battle assessment revealed that only 17 of the 44 men in the first independent tank company had survived the engagement. The Marine casualties totaled eight killed and 22 wounded, most from Japanese artillery fire rather than direct action by the tanks themselves.

The engagement demonstrated that coordinated defensive fire, particularly from heavy machine guns loaded with armor-piercing ammunition, could neutralize Japanese light armor when applied systematically against known weak points. Colonel Shup’s afteraction report noted that the 50 caliber machine guns had performed beyond expectations against Japanese armor with several tanks disabled or abandoned solely due to sustained heavy machine gun fire.

The thin armor plating that had been measured on the captured HGO proved to be a consistent vulnerability across all nine vehicles engaged in the attack. Most significantly, the Japanese tank crews appeared to have no effective countermeasures against coordinated machine gun fire, suggesting that their training and tactics had not adapted to face opponents equipped with armor-piercing ammunition and pre-sighted defensive positions.

The first wave of landing vehicle tracked hit Bio’s reef at 0905 hours on November 20th, 1943, grinding across 3 ft of water while Japanese machine guns opened fire from concrete imp placements along the seaw wall. Colonel David Shupe, commanding Second Marines reinforced, rode in the lead LVT as his assault battalion spread across the lagoon in a ragged line that stretched nearly a mile from Green Beach to Red Beach 3.

The amphibious tractors lurched and wallowed through the shallow water, their crews manning twin 50 caliber machine guns mounted in sponssons on either side of the passenger compartments. The reef crossing took 18 minutes longer than planned, giving Japanese defenders time to man their positions and coordinate defensive fires.

From his position in the LVT cab, Shupe could see muzzle flashes winking from pillboxes and bunkers scattered across the narrow atal. Betto measured only 2 mi long and 800 yardds at its widest point. But the Japanese had fortified every inch of coral with interconnected strong points designed to deliver overlapping fields of fire across the beaches and inland approaches.

Intelligence estimates had identified over 500 defensive positions, ranging from simple rifle pits to massive concrete bunkers housing 8-in naval guns. The LVT crews began engaging targets as soon as they came within effective range. Gunner Sergeant Pete Kowalsski, manning the starboard 50 caliber on Shup’s vehicle, opened fire on a concrete imp placement near the pier at 400 yardds, walking his armor-piercing tracers across the firing aperture until the Japanese weapon fell silent. The sponsson mounted machine

guns provided the only heavy firepower available to the assault troops until they could get ashore and bring up their own weapons, making the LVT gunners critical to suppressing defensive positions during the vulnerable approach phase.

As the first tractors reached the seaw wall, Japanese type 95 HGO tanks emerged from concealed positions among the palm trees and debris piles in land. Three tanks appeared near the airirstrip, moving in single file along a coral road that ran parallel to Red Beach 2. Their crews had waited until the marine assault was fully committed to the landing before revealing their positions, hoping to catch the amphibious vehicles while they were still in the water and unable to maneuver effectively on land. Staff Sergeant Ray Morrison, commanding a machine gun section aboard LVT-14,

immediately shifted fire from the beach defenses to the approaching armor. At a range of 120 yards, his armor-piercing rounds struck the lead HGO’s turret face and hole front with visible effect. The tank’s movement became erratic as the crew struggled with spalling damage, and the psychological shock of repeated impacts against their thin armor protection.

Morrison’s sustained bursts methodically worked across the vehicle’s frontal arc, targeting vision ports and the gun mantlet, while his assistant gunner fed fresh belts of API ammunition into the weapon. The second HGO attempted to close the range by advancing directly toward the LVTs, but crossed into the field of fire of three different machine gun sections. Sergeant Mike Torres, firing from LVT7, engaged the tank’s left side at 90 yards, while Corporal Jim Walsh and Corporal Danny Sullivan concentrated on the turret and engine deck from different angles.

The crossfire created multiple impact points across the thin armor plating with each 50 caliber round that achieved penetration, sending steel fragments ricocheting through the crew compartment. Within 2 minutes of sustained fire, the tank slooed to a stop with smoke rising from the engine compartment.

The third Japanese tank managed to reach firing position behind a coral embankment and engaged the LVTs with its 37mm gun. The first round struck LVT11 in the bow, penetrating the thin aluminum armor and killing two Marines in the passenger compartment.

The second shot hit LVT-15 in the engine compartment, disabling the vehicle and forcing its crew to abandon ship in chest deep water. But the tank’s firing position exposed its flanks to machine gun fire from multiple directions, and the LVT gunners quickly concentrated on the revealed target. Gunner Sergeant Kowalsski, now at a range of 70 yards, delivered precision fire against the Hugo’s turret ring and vision ports.

His armor-piercing round struck with sufficient force to jam the turret traverse mechanism and destroy the main gun site, effectively blinding the crew and preventing them from engaging additional targets. Simultaneously, machine gunners from two other LVTs worked over the tank’s side and rear armor, achieving multiple penetrations that filled the crew compartment with spall fragments and disabled the vehicle’s electrical systems. The engagement lasted less than 8 minutes from first contact to the destruction of all three Japanese tanks.

Post- battle examination revealed that sustained 50 caliber fire had achieved numerous complete penetrations of the Hogo armor, with some vehicles showing more than 20 holes punched through various sections of the hull and turret. The thin plating that measured 6 to 12 mm thick had provided no effective protection against armor-piercing ammunition fired from stable platforms at ranges under 200 yd.

Colonel Shup’s assault battalions continued across the reef and established footholds on red beaches 1 and two by 1100 hours. The LVT-mounted machine guns proved critical during the initial phase of the landing, providing the heavy firepower necessary to suppress Japanese strong points. While the infantry organized for the advance inland, several LVT commanders reported that their 50 caliber weapons had been more effective against Japanese armor than anticipated with multiple tank kills achieved using only machine gun fire and no support from dedicated anti-tank weapons. By the afternoon of

November 21st, Marine infantry had captured most of the airirstrip and were advancing toward the eastern end of the island. Japanese resistance remained fierce, but the destruction of the Hoggo tanks during the landing had eliminated the enemy’s primary mobile reserve.

Without armor support, Japanese counterattacks were limited to infantry assaults that could be broken up by concentrated small arms fire and artillery support from ships offshore. The division afteraction report specifically noted the effectiveness of LVT-mounted 50 caliber machine guns against Japanese light armor.

Recommendations included increasing the ammunition load for armor-piercing rounds in future amphibious operations and ensuring that LVT crews received specific training in anti-tank gunnery techniques. The report observed that Japanese tank crews appeared to have no effective countermeasures against sustained heavy machine gun fire, suggesting that their armor protection and tactical doctrine had not adapted to face opponents equipped with armor-piercing ammunition and trained in precision gunnery.

Technical Sergeant Morrison, who had participated in both the Guadal Canal and Terawa engagements, noted significant improvements in marine anti-tank techniques between the two operations. The LVT crews at Terawa had applied lessons learned from the Matanika River Crossing using controlled bursts and systematic target coverage to achieve maximum effectiveness against thin Japanese armor.

The stable firing platform provided by the amphibious tractors allowed for precision shooting that had been difficult to achieve from hastily prepared defensive positions in jungle terrain. Most significantly, the Terawa engagement demonstrated that Japanese light tanks could be neutralized by standard marine heavy weapons when employed with proper tactics and ammunition.

The Type 95 HGO had proven vulnerable to 50 caliber armor-piercing fire at all combat ranges with complete penetration achieved consistently against frontal, side, and rear armor. This vulnerability extended beyond the armor plating itself to include critical systems like vision devices, weapon mounts, and mechanical components that could be disabled or destroyed by precisely aimed heavy machine gun fire.

The night counterattack began at 2345 hours on June 16th, 1944 when Colonel Tadashi Gooto’s tank regiment emerged from the sugarce fields north of Saipan’s Aso airfield. Between 30 and 40 Japanese tanks rolled forward in the darkness, their engines muffled by the dense vegetation until they were within 200 yards of the second marine division’s perimeter.

Type 95 Hgo light tanks formed the spearhead, followed by heavier type 97 chihaw medium tanks carrying infantry squads clinging to their holes and turrets. The attack represented the largest coordinated armor assault Japanese forces had attempted against American positions since the start of the Pacific War. Major General Thomas Watson, commanding Second Marine Division, had anticipated the counterattack based on intelligence reports and aerial reconnaissance that showed Japanese armor concentrating in the island’s interior. His defensive

preparations reflected lessons learned from previous engagements with Japanese light tanks. Heavy machine gun sections had been positioned in depth throughout the marine lines with interlocking fields of fire across the most likely approach routes.

37mm anti-tank guns covered the main avenues of advance while bazooka teams occupied forward positions where they could engage enemy armor at close range. Lieutenant Colonel Willie Jones commanding first battalion sixth Marines watched the Japanese approach from his command post behind the front lines.

The enemy tanks moved without headlights, navigating by compass bearing and terrain features in a coordinated advance that suggested careful rehearsal during daylight hours. Infantry companies rode on the tank holes in the German manner, using the vehicles as mobile cover while advancing toward the marine positions.

Additional rifle squads moved on foot between the tanks, ready to exploit any breakthrough the armor achieved or to provide close support if the tanks encountered obstacles. The engagement opened when Japanese tanks reached the outer edge of the Marine defensive zone at midnight. Star shells burst overhead as artillery forward observers called for illumination, casting harsh shadows across the sugarcane field and revealing the full scope of the enemy assault.

Staff Sergeant Mike Torres, now commanding a heavy weapons section with First Battalion, opened fire with his Browning M2 at a range of 150 yards, targeting the lead HGO with sustained bursts of armor-piercing ammunition. His round struck the tank’s frontal armor with visible flashes, and Torres could see Japanese infantry tumbling from the hull as spalling fragments filled the crew compartment. Within minutes, the entire marine line erupted in coordinated defensive fire.

Heavy machine guns engaged Japanese tanks from multiple positions, creating crossfires that swept the infantry off the tank holes before they could deploy effectively for ground combat. Technical Sergeant Ray Morrison, firing from a prepared position on the battalion’s left flank, concentrated on vision ports and optical devices, systematically blinding the tank crews and forcing them to operate without effective observation of the battlefield.

His precise shooting disabled the main gun site on one HGO and jammed the turret traverse mechanism on another, rendering both vehicles ineffective as fighting platforms. The Japanese tanks pressed forward despite mounting casualties, attempting to close the range where their 37mm guns would be most effective against marine positions.

Several hogos penetrated the outer defensive line and engaged marine foxholes at pointblank range, but their thin armor made them vulnerable to close-range attacks by bazooka teams and individual Marines armed with magnetic anti-tank mines. Corporal Jim Walsh, carrying an M901 anti-tank rifle grenade, disabled two Japanese tanks by targeting their track mechanisms and road wheel assemblies, immobilizing the vehicles where concentrated machine gun fire could finish them. The coordinated nature of the Japanese attack began to

break down as communications failed between tank crews. Without radios, the armor units relied on visual signals and predetermined movement patterns that became impossible to maintain under heavy fire and battlefield illumination.

Individual tanks continued forward or attempted to withdraw independently, losing the mutual support that had made the initial assault effective. Some crews abandoned their vehicles after taking multiple penetrating hits, while others fought from stationary positions until their ammunition was exhausted or their weapons were disabled.

Captain Norman Thomas, commanding headquarters company, First Battalion, Sixth Marines, moved forward to coordinate the defense of a critical road junction where several Japanese tanks had penetrated the marine lines. His position came under direct fire from a type 97 Chiha medium tank whose thicker armor had allowed it to survive the initial machine gun engagement. Thomas called for fire support from a 75mm halftrack positioned in reserve, directing the vehicle to engage the Japanese tank from a flanking position where its sidearm would be vulnerable to the larger gun. The halftrack’s 75 mm rounds achieved immediate penetration of

the Chihaw’s side armor, setting fire to the vehicle’s ammunition storage and killing the crew. But Thomas’s exposed position drew fire from Japanese infantry who had dismounted from other tanks and were fighting as ground troops among the sugarce.

A rifle grenade exploded near his foxhole, wounding Thomas severely and forcing him to turn command over to his executive officer while continuing to direct fire support until medical personnel could evacuate him. By 0200 hours, the Japanese counterattack had lost momentum as tank after tank was knocked out or abandoned. Marine artillery began falling on the enemy assembly areas behind the forward line of contact, disrupting attempts to reinforce the attack with fresh troops or ammunition supplies. The concentrated defensive fires had separated the Japanese tanks from their supporting

infantry, leaving the armor units isolated and vulnerable to coordinated attacks by multiple marine weapons systems. Dawn revealed 31 Japanese tank carcasses scattered across the sugarce field between the marine lines and the enemy’s starting positions.

Post battle examination showed that heavy machine gun fire had been responsible for disabling or destroying more than half of the Japanese vehicles with complete penetrations of the thin Ho armor achieved at ranges up to 300 yards. Several tanks showed evidence of internal fires started by armor-piercing incendiary rounds, while others had been abandoned after spalling damage made them uninhabitable for their crews.

The Marine casualties from the night engagement totaled 43 killed and 112 wounded, remarkably light considering the scale of the Japanese attack. Most of the American losses had occurred during the initial phase of the assault when enemy tanks achieved temporary penetrations of the defensive line before being contained by coordinated counterattacks.

The successful defense demonstrated that Japanese armor tactics, which had proven effective against poorly equipped opponents earlier in the war, were inadequate against well-prepared American positions defended by troops trained in anti-tank techniques and equipped with appropriate weapons and ammunition. Colonel Gooto was found dead beside his command tank the following morning, killed by machine gun fire while attempting to direct the withdrawal of surviving vehicles.

His death marked the effective end of organized Japanese tank operations on Saipan as the remaining armor units lacked the leadership and coordination necessary to mount additional large-scale attacks. The destruction of the tank regiment also eliminated the enemy’s primary mobile reserve, forcing Japanese forces to rely on static defensive positions for the remainder of the campaign.

The division afteraction report noted that sustained 50 caliber machine gun fire had proven consistently effective against Japanese light armor when applied systematically against known weak points. The engagement confirmed that American heavy weapons, when properly employed with armor-piercing ammunition and coordinated fire control, could neutralize enemy tank attacks without requiring support from dedicated anti-tank guns or friendly armor units.

The Japanese counterattack across Palu airfield began at 14:30 hours on September 15th, 1944 as 11. Type 95 Hgo tanks raced from concealed positions among the coral ridges toward the flat expanse of crushed coral that served as the island’s main runway.

Colonel Kuno Nakagawa had ordered the assault as a desperate attempt to drive the First Marine Division back to the beaches before American forces could consolidate their hold on the strategic airfield. The tanks moved in a ragged line across the open ground. Their crews knowing they faced almost certain destruction, but following orders that demanded total commitment to stopping the Marine advance.

Lieutenant Colonel Lewis Puller, now commanding First Marines, watched the attack develop from his observation post on the southern edge of the airfield. The Japanese had chosen the worst possible terrain for an armored assault, crossing 1,500 yd of open coral flat that offered no cover and had been presited by every Marine heavy weapon within range. Intelligence reports indicated that Nakagawa’s garrison had fewer than 20 operational tanks remaining after 2 weeks of preliminary bombardment, making this counterattack a final gamble with the last mobile reserve available to the Japanese defenders. The leado had covered less than 300 yd when marine heavy machine guns opened fire from

prepared positions around the airfield perimeter. Staff Sergeant Mike Torres, commanding a weapon section with First Battalion, engaged the nearest tank at 400 yardds with sustained bursts of armor-piercing ammunition. His round struck the vehicle’s frontal armor and turret face with immediate effect, creating visible impact craters and sending spall fragments ricocheting through the crew compartment.

The tank continued forward, but began weaving erratically as the driver struggled with the effects of repeated armor penetrations. Technical Sergeant Ray Morrison, firing from a reinforced position on the airfield’s eastern edge, systematically worked over the second Japanese tank with precision bursts aimed at specific weak points.

His armor-piercing rounds targeted the vision ports and periscope mounts, destroying the crew’s ability to observe the battlefield and navigate effectively across the broken coral surface. Within 2 minutes of sustained fire, Morrison had achieved multiple complete penetrations of the thin armor plating and smoke began rising from the vehicle’s engine compartment as incendiary compounds ignited fuel and lubricating oil.

The Marine defensive fire created an interlocking web of tracers across the airfield that caught the Japanese tanks in a killing zone where escape was impossible. Heavy machine guns positioned at different points around the perimeter delivered crossfire that struck the Hugos from multiple angles simultaneously, overwhelming the thin armor protection in small crews that characterized Japanese light tank design.

Individual tanks tried to change direction or increase speed to escape the concentrated fire, but the open terrain offered no cover, and the pre-sighted weapons followed their movement with devastating accuracy. Marine M4 A2 Sherman tanks positioned in hold down firing positions behind coral embankments engaged the Japanese armor with 75 mm high explosive and armor-piercing rounds at ranges approaching 800 yardds.

The Sherman crews had clear fields of fire across the entire airfield and could engage multiple targets without changing position or exposing themselves to return fire. Tank Commander Sergeant Firstclass Jim Walsh reported achieving direct hits on three HOS within the first 5 minutes of the engagement with each 75 mm round completely destroying its target upon impact. Aircraft from Marine Fighter Squadron.

214 joined the engagement at 1445 hours, strafing the surviving Japanese tanks with 50 caliber machine gun fire and a 5-in high velocity aircraft rockets. The Corsair fighters made repeated passes across the airfield, coordinating their attacks with ground forces to avoid hitting friendly positions while delivering precision fire against the remaining enemy armor.

Pilot Captain Danny Sullivan reported that several Japanese tanks were abandoned by their crews after taking multiple hits from aircraft weapons, leaving the vehicles motionless on the Coral Strip where ground forces could finish them with direct fire. The Japanese infantry supporting the tank attack suffered severe casualties as they attempted to cross the open airfield on foot.

Marine riflemen and machine gunners targeted the dismounted troops with concentrated small arms fire that prevented them from reaching effective range of American positions. Without the protection of terrain features or prepared fortifications, the Japanese soldiers were forced to advance across ground that offered no concealment from observation or cover from fire.

Most of the infantry casualties occurred during the first 10 minutes of the attack before the surviving troops could find shelter in shell craters or behind disabled vehicles. By 1500 hours, the Japanese counterattack had collapsed completely. Nine of the 11 HGO tanks lay burning or abandoned on the airfield, their thin armor no match for the concentrated fire of multiple marine weapon systems.

The two surviving tanks had turned back toward the coral ridges, but both were disabled by aircraft attacks before reaching cover. Post engagement assessment revealed that sustained 50 caliber machine gun fire had been responsible for disabling or destroying six of the Japanese vehicles, demonstrating once again that American heavy weapons could neutralize enemy light armor when properly employed with armor-piercing ammunition.

Colonel Nakagawa’s decision to commit his last armored reserve in a daylight assault across open terrain represented a fundamental misunderstanding of American defensive capabilities and the vulnerability of Japanese light tanks to coordinated heavy weapons fire. The attack achieved no tactical objectives and eliminated the enemy’s remaining mobile forces, leaving the Japanese garrison dependent entirely on fixed fortifications for the remainder of the campaign.

Marine intelligence officers noted that the enemy’s willingness to sacrifice his armor in such an obviously hopeless attack suggested that Japanese commanders had few realistic options remaining for defending the island. The Marine casualties from the airfield engagement totaled seven killed and 19 wounded. Remarkably light considering the intensity of the fighting.

Most American losses had occurred when Japanese artillery fired on marine positions during the tank attack rather than from direct action by enemy armor or infantry. The successful defense confirmed that Japanese light tank tactics, which had proven marginally effective in jungle terrain with limited visibility, were completely inadequate against American forces fighting from prepared positions on open ground with clear fields of fire.

Technical analysis of the destroyed Japanese tanks revealed consistent patterns of damage that validated American anti-tank techniques developed through previous engagements. Heavy machine gun fire had achieved numerous complete penetrations of HGO armor at ranges up to 500 yardds with armor-piercing incendiary rounds creating internal fires and spall damage that made the vehicles uninhabitable for their crews.

The systematic destruction of vision devices and optical equipment had blinded tank crews and prevented effective return fire, while concentrated fire against mechanical components had disabled several vehicles without achieving complete armor penetration. The division’s ammunition expenditure report documented the consumption of 693,657 rounds of 50 caliber ammunition during the entire Pleu campaign, indicating the central role that heavy machine guns played in marine offensive and defensive operations.

The airfield engagement alone accounted for approximately 8,000 rounds of armor-piercing ammunition fired by 12 heavy machine gun sections over a 30inut period. This massive expenditure of ammunition reflected both the intensity of the fighting and the Marines confidence in using 50 caliber weapons as primary anti-tank systems against Japanese light armor.

The destruction of Nakagawa’s last tank reserve marked the end of organized Japanese armored operations in the Pacific theater. Subsequent enemy counterattacks relied entirely on infantry assault tactics, often supported by individual tanks or self-propelled guns operating from static positions. The consistent failure of Japanese light armor against American heavy weapons had forced enemy commanders to abandon mobile tank tactics in favor of using their remaining vehicles as fixed pill boxes.

Acknowledging that the thin armor and small crews of Hugo tanks could not survive coordinated attacks by welle equipped Marine units trained in precision anti-tank gunnery.