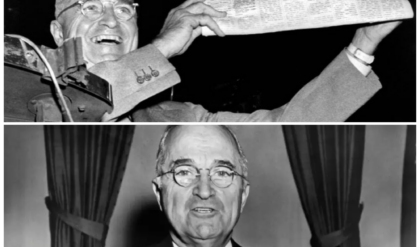

January 20th, 1953, Independence, Missouri. The cold bit through Harry Truman’s coat as he stood on the front porch of 219 North Delaware Street, a ramshackle Victorian house that had belonged to his mother-in-law. No secret service detail, no motorcade, no cheering crowds, just a 68-year-old man fumbling with his house keys because he couldn’t quite get them to turn in the frozen lock. 8 years earlier, he had commanded the most powerful military force in human history.

He had dropped the atomic bomb. He had rebuilt Europe. He had stared down Stalin. He had integrated the armed forces. He had made decisions that shaped the entire world. But today, today, President Harry Truman couldn’t afford to hire someone to fix his front door.

His bank account held less than most of the factory workers at the automobile plant across town. His only steady income was a military pension of $11,256 per month, the equivalent of about $1,200 today. In his pocket sat a stack of job offers from the United States biggest corporations. Each one promising him more money in a single year than most Americans would see in a lifetime.

Six figure salaries, corner offices, his name in gold letters on the door. All he had to do was say yes. But what the corporate executives sending those letters didn’t understand, what they couldn’t understand was that they weren’t dealing with an ordinary man.

They were dealing with someone who believed that some things couldn’t be bought, that some offices shouldn’t be sold, that dignity had a price, and President Harry Truman refused to pay it. How does the most powerful man in the world end up nearly broke? Why would a president who could have made millions choose poverty instead? And what happened when the United States realized it had left its former leader struggling to pay his heating bills? This is the story of how one man’s integrity created a crisis that changed the presidency forever. And how everything we thought we knew about his poverty might have been the greatest con in American

political history. A story where the hero might actually be the villain. Where the poorest president might have been secretly rich, where nothing is quite what it seems. If you’re the kind of person who loves discovering how history’s biggest heroes were actually far more complicated than the legends suggest, hit that subscribe button right now and drop a comment.

Where are you watching from? And which president do you think history has gotten completely wrong? To understand how President Harry Truman became the only American president to leave office poorer than when he entered, we need to go back three decades before that frozen January morning. We need to go back to 1922, Kansas City, Missouri.

The smell of new fabric and fresh paint filled the air of Truman and Jacobson, a men’s clothing store on West 12th Street. Harry Truman, 38 years old, stood behind the counter arranging silk ties imported from New York. Business was booming. The First World War had just ended. Soldiers were coming home flush with cash, and every man wanted a new suit to celebrate peaceime prosperity. President Harry Truman had everything figured out.

He’d survived the trenches of France as an artillery captain. He’d come home a war hero. He’d married his childhood sweetheart, Bess Wallace, a woman from one of Independence’s most prominent families, the kind of woman who’d grown up in a house with servants and crystal chandeliers. Now he was going to make his fortune selling shirts and hats to Kansas City’s growing middle class.

The store shelves were stocked with the finest merchandise money could buy. Custommade suits from Chicago, leather gloves from Italy, silk shirts that cost more than a factory worker’s weekly salary. Young Harry Truman was going to show Bess’s family that a farmer’s son could make it in the city, that he was worthy of marrying into the Wallace family, that he was going to be somebody. Then the economy collapsed.

The recession of 1921 to 1922 hit the United States like a freight train nobody saw coming. Unemployment tripled overnight. Stock prices plunged 40%. Banks failed across the Midwest. And suddenly, nobody needed a $5 silk tie or a $25 suit. Men who’d been spending freely just months before were now standing in bread lines. Within 18 months, Truman and Jacobson was drowning in debt. The creditors circled like sharks.

The bills piled up faster than they could count them. $12,000 in debt, equivalent to nearly $200,000 today. His partner, Eddie Jacobson, filed for bankruptcy, walking away from the debts legally, starting fresh. But President Harry Truman made a different choice.

A choice that would haunt him for the next 15 years and define his character for the rest of his life. He refused to declare bankruptcy. “I’m going to pay every cent back,” he told Bess. Even as the creditors circled and the collection notices piled up on their kitchen table, even as his bank account hit zero. Even as they had to move into Bess’s mother’s house at 219 North Delaware because they couldn’t afford their own place.

Even as Bess’s wealthy relatives whispered about how she’d married beneath herself, how they’d known all along that Harry Truman would never amount to anything. For 15 years, 15 years, President Harry Truman sent checks to his creditors. Small checks, sometimes just five or $10 at a time, money scraped together from odd jobs, from his salary as a county judge, from anywhere he could find it. Picture this. It’s 1936.

Harry Truman is 52 years old. He’s just been elected to the United States Senate, one of the most prestigious positions in American government. He’s one of only 96 men in the entire country chosen to represent their states in Washington, and he’s still paying off debt from a business that had failed when Herbert Hoover was president 14 years earlier. His Senate colleagues drove new Cadillacs and lived in Georgetown mansions.

President Harry Truman took the street car and counted pennies. That’s who President Harry Truman was. A man who believed you paid your debts. A man who believed your word was your bond. A man who would rather spend 15 years in poverty than break a promise.

A man whose stubbornness was legendary, whose integrity was unshakable, whose sense of honor was so rigid it bordered on the fanatical. But here’s what nobody understood in 1922. As young Harry closed the doors of his failed habeddasherie for the last time, as he swept the floor one final time and locked the door behind him, that financial disaster wasn’t his ending. It was his education.

It was the forge in which his character was hammered into steel. Because 18 years later, that same stubborn, failed shopkeeper would become vice president of the United States. And 82 days after that, when Franklin Roosevelt’s heart gave out in Warm Springs, Georgia, that man who couldn’t keep a clothing store solvent would inherit command of a nation fighting the biggest war in human history. The phone call came at 5:25 in the afternoon on April 12th, 1945.

President Harry Truman was having a drink in the Capitol building when he was told to rush to the White House immediately. No explanation, just urgency in the voice on the other end of the line. He arrived to find Eleanor Roosevelt waiting in the family quarters. She was wearing black. Her eyes were red from crying.

She placed her hand on his shoulder. And in that moment, before she even spoke, President Harry Truman knew what had happened. Harry,” she said softly, her voice barely above a whisper. “The president is dead.” The room seemed to tilt. The walls closed in. For a moment, President Harry Truman couldn’t speak. Couldn’t breathe.

The weight of what was about to fall on his shoulders pressed down on him like a physical force. Finally, he managed to choke out a question. “Is there anything I can do for you?” Elellanar Roosevelt looked at him. this man from Missouri who’d failed at business, who’d struggled with debt for decades, who’d never graduated college, who’d never expected or wanted to be president, who’d been kept so far out of the loop that he didn’t even know about the atomic bomb.

She squeezed his shoulder, and when she spoke, her words would prove more prophetic than either of them could have imagined. “Is there anything we can do for you?” she replied, her voice thick with emotion and concern. “You’re the one in trouble now.” She had no idea how right she was.

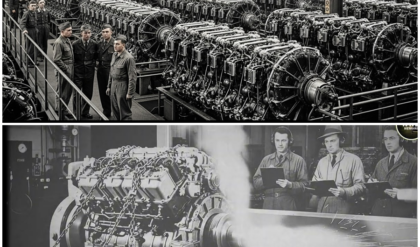

She had no idea that the troubles facing President Harry Truman would extend far beyond the war, far beyond the presidency, far into a retirement that would test his principles in ways the White House never could. President Harry Truman inherited more than a presidency on that April evening in 1945. He inherited a secret so explosive that not even the Vice President, not even Hel. 14 days into his presidency, Secretary of War Henry Stimson requested an urgent meeting, the old man’s hands trembled as he opened a locked briefcase and pulled out a file marked with the highest classification level President Harry

Truman had ever seen. What Stimson told him over the next hour made Truman’s blood run cold. The United States had built a bomb, a weapon of unimaginable destructive power. A single bomb that could obliterate an entire city, vaporize buildings, turn people into shadows burned into concrete.

a bomb that harnessed the power of the sun itself, splitting atoms in a chain reaction that released energy equivalent to 20,000 tons of TNT. Scientists called it the atomic bomb. They’d been working on it in secret for 3 years. They’d spent $2 billion of taxpayer money, equivalent to 30 billion today, on a project so classified that Congress didn’t even know about it.

Franklin Roosevelt had known. Winston Churchill had known. Joseph Stalin probably knew. But President Harry Truman, the vice president of the United States, had been kept completely in the dark. And now, this man who’d failed at selling men’s clothing.

This man who’d spent 15 years paying off a $12,000 debt had to decide whether to use this weapon, whether to incinerate hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians in seconds, whether to unleash nuclear fire on the world. The weight of that decision would have crushed most men. President Harry Truman didn’t sleep for weeks.

He walked the halls of the White House at 3:00 in the morning alone with the burden of what he knew. His military advisers told him that invading Japan would cost a million American lives. The Japanese were training women and children to fight with sharpened bamboo spears. Every man, woman, and child on the Japanese home islands had been ordered to resist to the death. The casualties would be unlike anything in human history.

But using the bomb, using this bomb, on July 25th, 1945, President Harry Truman wrote in his diary, “We have discovered the most terrible bomb in the history of the world. It may be the fire destruction prophesied in the Euphrates Valley era after Noah and his fabulous ark.

” The next day, he authorized its use against Japan. On August 6th, the Anola Gay, a B-29 bomber piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbitz, dropped Little Boy on Hiroshima. The bomb detonated at 8:15 in the morning, 1,900 ft above the city, a flash of light brighter than the sun, a fireball that reached several million degrees. A shock wave that flattened everything within a mile. 70,000 people died instantly.

Their shadows were burned into the walls. The city ceased to exist. 3 days later, another bomb, Fat Man, fell on Nagasaki. 40,000 more people dead in a flash of light hotter than the surface of the sun. Japan surrendered 6 days after that. The Second World War, the bloodiest conflict in human history, was over.

50 million people had died. President Harry Truman had ended it by unleashing a weapon so terrible that it would haunt humanity for generations. And he never slept soundly again. Years later, when asked if he regretted the decision, President Harry Truman would snap, “Hell no, I’d do it again.

” But those who knew him well said he woke up screaming sometimes decades after the war. that he couldn’t watch fireworks without flinching, that he saw the faces of Hiroshima in his dreams, but the bombs were just the beginning. The challenges facing Truman’s presidency came faster than a machine gun, each one seemingly designed to destroy his political career.

Should the United States help rebuild Europe or let it collapse into Soviet hands? The Marshall Plan would cost billions, equivalent to hundreds of billions today. Taxpayers were furious. Americans were tired of war, tired of sacrifice, tired of sending money overseas. But President Harry Truman pushed it through anyway because he believed letting Europe starve would guarantee another world war.

Should he integrate the armed forces and risk losing the Democratic South? The Southern Democrats, the Dixierats, threatened to abandon the party entirely if he dared to let black soldiers serve alongside white soldiers. President Harry Truman’s advisers begged him not to do it. It would destroy his presidency. They said he’d never win re-election.

But on July 26th, 1948, he signed Executive Order 9981, desegregating the military. The South exploded in fury. Strom Thurman ran against him as a segregationist candidate. It nearly cost him the election should he fire the most popular general in the United States, Douglas MacArthur, for insubordination during the Korean War.

MacArthur was a legend, a hero. He’d liberated the Philippines. He’d rebuilt Japan. The American public worshiped him. But when MacArthur publicly contradicted the president’s orders when he threatened to expand the Korean War into China and risk starting World War II with nuclear weapons, President Harry Truman made the hardest decision of his presidency. On April 11th, 1951, he fired MacArthur.

The country lost its mind. When MacArthur returned to the United States, 7 and a half million people lined the streets of New York to welcome him home. It was the largest parade in American history, larger than the celebrations after World War II.

The crowds screamed, “Impeach Truman and burned the president in effigy.” Congressman called President Harry Truman a traitor. Newspapers demanded his resignation. His approval rating dropped to 22%, the lowest in recorded history at that time. Every decision President Harry Truman made seemed designed to make him the most hated man in the United States. He supported civil rights when the South demanded segregation.

He fought to expand social security when conservatives called him a socialist. He contained communism when isolationists wanted to ignore the Soviet threat. He built NATO when Americans were tired of foreign entanglements. He stood up to Stalin at Potam when appeasement seemed easier and the United States repaid him with contempt.

By 1952, President Harry Truman was exhausted, hated, broken. When he walked down the street, people booed him. When he attended baseball games, crowds jeered. The Chicago Tribune, one of the nation’s largest newspapers, ran the headline, “Trum should be impeached.” Senator Joseph McCarthy called him a traitor who’d lost China to communism.

The Republican National Committee created a popular poster showing Truman’s face with the caption, “Had enough.” The United States answer in the November election was a resounding yes. President Harry Truman chose not to run for reelection. The Democrats nominated Adli Stevenson instead.

Dwight Eisenhower, the general who’ commanded D-Day, the most beloved military figure in the United States, won in a landslide, campaigning against what he called Korea, communism, and corruption. On January 20th, 1953, President Harry Truman and his wife Bess boarded a train back to Independence.

There were no farewell parades, no thank you dinners, no corporate jets offering to fly them home, no outpouring of gratitude from a nation he’d served for nearly 8 years, just a couple of regular train tickets, two suitcases, a box of personal papers, and a small secret service detail that would soon disappear. When President Harry Truman walked through the front door of 219 North Delaware Street that cold January afternoon, he carried approximately $13,000 in savings, about $130,000 in today’s money. That was it. the sum total of wealth accumulated by the man

who’d run the most powerful nation on Earth for nearly eight years, who’d authorized the atomic bomb, who’d saved Europe, who’d stood up to Stalin, who’d integrated the military, who’d made decisions that affected billions of lives. $13,000. And the letters, they started arriving within days.

The first offer arrived less than a week after President Harry Truman returned to Independence. The letter head was expensive, embossed, heavy stock, the kind of paper that announced wealth before you even read the words. A major insurance company. Would the former president be interested in joining their board of directors? The work would be minimal, four meetings per year, perhaps a speech or two.

They would pay him $100,000 annually, nearly $1 million in today’s currency. For four meetings a year, President Harry Truman read the letter three times. Then he folded it carefully, placed it in a drawer, and never responded. The letters kept coming. Every day brought new offers, each more lucrative than the last.

A Wall Street investment bank wanted him as a consultant, 150,000 per year. They’d even provide an office in Manhattan if he preferred to work from New York instead of Missouri. A manufacturing company wanted his name on their board. 125,000 per year, plus stock options that could be worth millions. A Miami real estate developer made the most audacious offer of all.

$100,000 for a single appearance at a housing development grand opening. One hour of his time. Shake some hands. Cut a ribbon. Smile for the cameras. $100,000. In today’s currency, that’s nearly $1 million for one hour of work.

President Harry Truman’s friends thought he was insane not to take at least some of these offers. His wife Bess worried constantly about their finances. Their daughter Margaret, a professional singer trying to build her own career, begged her father to at least consider the possibilities. They could secure their financial future forever with just one or two of these contracts.

But President Harry Truman wouldn’t budge. He sat at his desk in the small office he’d rented in Kansas City and composed the same response to every offer, his fingers hammering away at an old typewriter. I could never lend myself to any transaction, however respectable, that would commercialize on the prestige and dignity of the office of the presidency. He meant it, every word.

Don’t you understand? He told Bess one evening as she worried over their household budget. If I go sit on some board just because I was president, I’m telling every American that their presidency, their office, because it belongs to them, not to me, can be bought.

I’m telling them that the man who ordered the atomic bomb, who saved Europe, who stood up to Stalin, will dance for corporate America if the price is right. But Harry, best pleaded, “We need the money. We’ll manage,” he said, his jaw set in that stubborn way that meant the conversation was over. But integrity doesn’t pay the bills. And managing was getting harder every day.

By his first full year back in independence 1954, Truman’s annual income was exactly $13,564.74. [Music] His Army Reserve pension provided $11,256 per month, $1,350.72 for the year. The rest came from selling some stock he’d accumulated and collecting small speaking fees when he absolutely had to. But the expenses, they were crushing.

President Harry Truman insisted on maintaining an office to handle the correspondents that still flooded in hundreds of letters every week from Americans who wanted advice, who wanted autographs, who wanted to share their thoughts with the former president. He hired two secretaries. He rented office space in downtown Kansas City. He bought filing cabinets, typewriters, postage stamps, stationery. By his own accounting, he spent $30,000 that year, more than twice his income on office expenses and staff salaries.

The house at 219 North Delaware Street needed repairs desperately. The roof leaked every time it rained. Water stains spread across the ceiling plaster. The plumbing was falling apart. Pipes that groaned and clanked and sometimes burst in the winter. The heating system barely worked.

On cold Missouri nights, President Harry Truman, the man who’d authorized the Marshall Plan that rebuilt all of Europe, wore two sweaters to bed because he couldn’t afford to fix his own furnace. Bess’s inheritance from her mother had been modest. $8,385.90 after the estate was divided among the four siblings.

That money was already gone, spent on immediate repairs and daily expenses. President Harry Truman took out a loan from his bank in Washington just to keep afloat. He never disclosed the amount publicly. But the fact that a former president of the United States needed to borrow money to survive was humiliating, embarrassing, a stain on the dignity of the office he’d worked so hard to protect. His contemporaries weren’t struggling like this.

Herbert Hoover, the only other living former president, was a multi-millionaire many times over from his mining investments and business ventures before entering politics. Hoover lived in a suite at the Waldorf Histori in New York, one of the most expensive hotels in the United States. He traveled the world. He collected rare books. He wanted for nothing.

And Dwight Eisenhower, the man who’d replaced President Harry Truman in the White House. Within months of leaving office in 1961, Eisenhower would sign a book deal for his war memoirs worth $635,000, over 6 million in today’s currency. Even better, the Internal Revenue Service ruled that because Eisenhower wasn’t a professional writer, he could treat the entire sum as a capital gain instead of ordinary income.

The difference in tax rates meant Eisenhower kept over $500,000 after taxes. Meanwhile, President Harry Truman sat in his drafty independence house, wearing two sweaters against the cold, trying to figure out how to pay next month’s heating bill. The bitterness grew. The resentment festered.

Why was he being punished for his integrity? Why was he suffering while Hoover lived in luxury and Eisenhower cashed enormous checks? Had the United States no gratitude? No sense of obligation to its former leaders? By 1956, President Harry Truman had reached his breaking point. February 1953, just one month after leaving the White House, President Harry Truman sat across from the representatives of Life magazine in his modest Kansas City office. They traveled from New York with an offer he couldn’t refuse and one he couldn’t quite believe. $600,000.

That’s what Life Magazine, one of the most influential publications in the United States, would pay for the exclusive rights to serialize his presidential memoirs. They wanted the inside story of the atomic bomb decision. The truth about Potam. The real story of firing MacArthur. Everything. $600,000. more money than President Harry Truman had seen in his entire life.

More than he’d earned in eight years as president of the United States, more than his father had made in a lifetime of farming. A fantastic sum, he would later call it in a private letter to his former Secretary of State, Dean Aerson. In today’s currency, it would be equivalent to over $6 million. Finally, President Harry Truman could breathe. He wouldn’t have to worry about the mortgage or the repairs or the office expenses anymore.

He could write his story, defend his presidency against all the critics who’d savaged him, set the historical record straight, and secure his financial future all at once. The memoirs would save him from poverty. They would justify his refusal to join corporate boards. They would prove he’d been right all along. Or so he thought.

What President Harry Truman didn’t know, what he couldn’t have known until he was deep into the project, was that writing presidential memoirs would be the hardest, most grueling, most financially devastating thing he’d ever done. Harder than running a business, harder than winning an election. In some ways, harder than being president.

For the next 3 years, President Harry Truman woke up at 5:30 every morning and drove to his office in Kansas City. He would sit at his desk surrounded by mountains of files and documents and handwritten notes trying to remember exactly what had happened on July 24th, 1945 when he’d first been briefed on the atomic bomb.

What had Stalin said to him at Potam? What expression had been on Churchill’s face? What had he been thinking in those final moments before he gave the order to drop the bomb? The work consumed him utterly. It wasn’t just writing, it was excavation, archaeology of memory. He had to verify every fact, check every date, confirm every conversation. He hired a staff of researchers. He brought in historians.

He needed secretaries to type and retype the manuscripts. He rented larger office space to store all the documents. The expenses piled up faster than he could track them. New filing cabinets, more typewriters, research materials, travel costs for interviews, salaries for the growing staff, office rent that climbed every year, postage for sending drafts back and forth to Life magazine’s editors in New York, phone bills from the constant long-distance calls.

By the time the memoirs were finally published, volume one in 1955, volume two in 1956, President Harry Truman had spent three years of his life and over $150,000 in expenses creating them. And then came the taxes. When the $600,000 finally came through, President Harry Truman discovered something that made him want to scream with frustration and fury.

The Internal Revenue Service considered his memoir income to be ordinary income, not capital gains. The tax rate for someone in his bracket was a staggering 70%. 70 cents of every dollar going straight to the federal government. Almost half the money vanished immediately to federal income tax. Another chunk disappeared to state taxes in Missouri. Then there were the business expenses.

3 years of office rent, staff salaries, research costs, equipment, supplies, everything. By the time President Harry Truman sat down with his accountant and tallied it all up, he’d netted approximately $37,000 from a $600,000 book deal. $37,000 over 5 years of backbreaking work. That’s $7,400 per year, barely more than he’d been making from his army pension.

The bitterness President Harry Truman felt about this was profound and all-consuming. Here was Dwight Eisenhower, a professional military officer who’d been ordered to write his memoirs as part of his military duties, getting to treat his book Advance as capital gains, and keeping over $500,000 after taxes. Meanwhile, President Harry Truman, who’d actually needed the money, who’d worked himself nearly to death producing the memoirs, who’d spent every cent he had on expenses, watched 94% of his book deal evaporate into taxes and overhead.

It wasn’t fair. It wasn’t right. And President Harry Truman decided he wasn’t going to suffer in silence anymore. In January 1957, President Harry Truman sat down and wrote a letter to House Majority Leader John McCormack. It was a letter that mixed pleading with barely concealed threats.

A letter that would within 18 months fundamentally transform how the United States treats its former presidents. “Dear John,” he began, and then launched into a detailed accounting of his financial struggles. The total overhead from February 1953 until November of last year, 1956, amounted to a sum over $153,000. Had it not been for the fact that I was able to sell some property that my brother, sister, and I inherited from our mother, I would practically be on relief. Practically on relief.

A former president of the United States, he continued, building to his central complaint. It seems rather peculiar that a fellow who spent 18 years in government service and succeeded in getting all these things done for the people he commanded should have to go broke in order to tell the people the truth about what really happened.

And then came the threat thinly veiled but unmistakable. I don’t want any pension and never have wanted any because I’ll manage to get along. But I am just giving you the difference in the approach between the great general and myself on the memoirs. My net return will be about $37,000 total over a 5-year period.

The great general was obviously Eisenhower. The sarcasm dripped from every word. President Harry Truman sent similar letters to other congressional leaders, including Speaker of the House Sam Raburn. In August 1957, he wrote to Rabburn. Sam, I’m not lobbying for the bill.

referring to proposed legislation to provide pensions for former presidents. But if it did not pass, I must go ahead with some contracts to keep ahead of the hounds. Translation: Give me a pension or I’ll be forced to do exactly what I’ve refused to do. Sell the dignity of the presidency to the highest bidder. But letters weren’t enough.

President Harry Truman needed a bigger stage. He needed to take his case directly to the American people. In early 1958, legendary journalist Edward R. Muro came to independence with a television crew. Muro was the most respected broadcast journalist in the United States.

The man who’d exposed Senator Joseph McCarthy’s witch hunts, who’d brought down a demagogue with nothing but facts and righteous anger. His program, See It Now, reached tens of millions of viewers. On February 2nd, 1958, 60 million Americans tuned in to watch President Harry Truman’s first major television interview since leaving office.

They saw him sitting in his modest independence home, looking every bit the humble, struggling former president, and they heard him make his case. “I could never lend myself to any transaction, however respectable, that would commercialize on the prestige and dignity of the office of the presidency,” he told Mo, his voice firm with conviction. Then he painted a devastating picture of his financial situation. The mountains of mail he had to answer. The office expenses.

The burden of being a former president of the United States without any government support whatsoever. The unfairness of watching other presidents get rich while he struggled. The American public was shocked. Their president, the man who’d won World War II, who’d saved Europe from communism, who’d stood up to Stalin, who’d integrated the armed forces, was struggling to pay his bills. It was unconscionable. It was unamerican.

It was a national disgrace. Congress moved with shocking speed. Within 6 months of Truman’s television appearance, both houses had passed the Former President’s Act. On August 25th, 1958, President Dwight Eisenhower signed it into law.

The act provided former presidents with an annual pension equal to a cabinet secretary’s salary, $25,000 per year, about $250,000 in today’s currency. It also covered office expenses, staff salaries, travel costs, health benefits for life, and funding for presidential libraries. President Harry Truman had won. His integrity had been vindicated. His suffering had been rewarded.

The United States had finally recognized that its former presidents deserve dignity in retirement, that they shouldn’t be forced to commercialize the office just to survive. The newspapers praised him. Historians called him a man of unshakable principle. His reputation, which had been so battered when he left office, began its long rehabilitation.

He was no longer the most hated president in the United States. He was becoming the most admired. President Harry Truman’s poverty had saved not just himself, but every future president. He’d created a lasting legacy of dignity. Except what if it was all a lie? What if I told you that almost everything you just heard was a carefully crafted fiction? What if President Harry Truman wasn’t poor at all when he left the presidency? What if the whole narrative of his financial struggles? The story that created an entire government entitlement program, the legend that inspired generations of

Americans was in fact the most successful conj job in United States political history. In 2021, a law professor named Paul Campos at the University of Colorado published a devastating article in the Michigan State Law Review. The article was titled The Truman Show: The Fraudulent Origins of the Former President’s Act.

Using newly released documents from Best Truman’s personal files, documents that had been sealed in the Truman Presidential Library for decades, Professor Campos proved something absolutely shocking. President Harry Truman was rich when he left the White House. Not comfortable, not middle class, rich, very rich. On his last day as president of the United States, Truman’s net worth was approximately $650,000, the equivalent of $6.

6 million in today’s currency. He had been secretly siphoning money from a presidential expense account for years. Technically legal, but ethically dubious at best, converting public funds that were meant for official entertaining into personal savings. Let me explain how this worked because it’s important.

Starting in 1949, Congress appropriated $50,000 per year, about $550,000 in today’s money, as a presidential expense account for official entertaining and related costs. This money was supposed to be spent on state dinners, diplomatic receptions, official functions. But there was no real oversight, no auditing, no requirement to prove the money had actually been spent on its intended purpose.

President Harry Truman took that money, all of it, or nearly all of it, and deposited it into his personal bank account. Over four years, from 1949 to 1953, he converted approximately $200,000 in government funds, $2.2 million in today’s currency, into personal wealth. Was it illegal? Technically, no. The law was vague enough that he could argue the money was his to use as he saw fit.

Was it ethical? That’s a very different question. The money was appropriated by Congress for official purposes and President Harry Truman used it to build his personal fortune. But wait, there’s more. So much more. The ramshackle house at 219 North Delaware Street that he supposedly moved into out of financial necessity.

Professor Campos’s research revealed that President Harry Truman had actually purchased the property during his presidency using his presidential salary. He owned the house outright. the repairs he claimed he couldn’t afford. He simply chose not to make them a decision about priorities and aesthetics, not poverty. The $11256 Army pension he claimed was his only income after leaving office.

Technically true in the narrowest possible sense, but breathtakingly misleading. President Harry Truman also had substantial rental income from the family farm properties that he and his siblings owned. He had investment dividends from stocks and bonds. He had the proceeds from the sale of farmland, which he conveniently forgot to mention in his letters to Congress about his financial struggles.

The $37,000 net profit he claimed from his $600,000 memoir deal. Creative accounting at its finest. Yes, the expenses were high. Yes, the taxes were substantial. But Professor Campos’s examination of Truman’s actual tax returns, which eventually became public records, showed that he was claiming business expenses that were actually personal living costs.

The office rent probably legitimate. But were all those staff salaries really necessary for the memoirs? Were all those research expenses actually related to the book, or were they just his general living expenses run through the business? President Harry Truman inflated his overhead dramatically to create the appearance of financial struggle.

Even the story about needing to take out a bank loan in his final weeks as president. Professor Campo searched exhaustively for evidence, bank records, personal correspondence, financial documents, nothing. No evidence that such a loan ever existed. It appears to have been a complete fabrication. First mentioned by Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer David McCulliff without any source citation, then repeated by every historian since because McCauliff said it, so it must be true.

The truth, President Harry Truman left the White House as a wealthy man. Within 5 years, he became even wealthier. By the time the former president’s act passed in 1958, his net worth had climbed to well over $1 million in 1950s currency, equivalent to roughly $10 million today. He didn’t need a pension. He didn’t need government benefits.

He was richer than 99% of Americans. President Harry Truman lied systematically, repeatedly, convincingly for years. He lied to Congress. He lied to the press. He lied to the American people. He created an entire fictional narrative of financial hardship and struggle. And he did it so skillfully that it became the accepted historical truth for over 60 years.

and he deeply bitterly resented the fact that his contemporaries could monetize their fame while he bound by his own rigid sense of propriety refused to do so. More than that, President Harry Truman was genuinely angry, furious about the tax treatment of Eisenhower’s memoirs.

It burned him with white hot intensity that Eisenhower got to treat his book income as capital gains while he got hammered with a 70% income tax rate. In Truman’s mind, this wasn’t just unfair. It was an insult, a betrayal. He’d saved the country, and the country was rewarding Eisenhower instead. So, he decided to get what he believed he deserved by other means.

President Harry Truman created a narrative, a story of a simple man from Missouri who’d served his country with honor and been left to struggle in poverty. A story specifically designed to tug at the United States heartstrings and open the United States wallet.

A story that positioned him as the moral opposite of grasping greedy former presidents who sold their dignity for corporate dollars. And it worked brilliantly, perfectly beyond his wildest dreams. The former president’s act passed with overwhelming bipartisan support. Republicans and Democrats alike voted for it. Nobody questioned whether President Harry Truman actually needed the money. Nobody audited his finances.

Nobody asked to see his bank statements or tax returns. The legend of his financial rectitude and principled poverty had become so powerful, so embedded in the national consciousness that even asking the question seemed like an insult to a great man.

President Harry Truman had played the role of the poor ex-president so convincingly that he’d essentially created an entire new government entitlement program, one that now costs taxpayers over $4 million annually based on a financial hardship that never actually existed. And here’s the final twist, the ultimate irony. Even after the former president’s act passed and President Harry Truman began receiving his $25,000 annual pension, he kept getting richer, much, much richer.

Between 1958 and his death in December 1972, President Harry Truman earned substantial income from speaking engagements. Despite his supposed reluctance to commercialize the presidency, he charged fees for appearances. He collected royalties from continued sales of his memoirs. He made savvy investments. He sold more family property at appreciated values.

By the time he died at age 88, President Harry Truman’s estate was worth several million dollars in 1970s currency, equivalent to tens of millions today. His wife Bess and daughter Margaret never worried about money again. President Harry Truman had successfully conned the United States Congress and the American people into giving him money he didn’t need based on poverty that didn’t exist while positioning himself as the last honest man in politics.

So what does this mean? What do we do with this information? The former president’s act still exists today more than 60 years after its creation and it’s grown metastasized become exactly what President Harry Truman claimed to despise. a way for former presidents to profit handsomely from holding office without doing anything to earn it. The four living former presidents as of today, Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, George W.

Bush, and Barack Obama each receive annual pensions of over $200,000. Each receives over $1 million in additional benefits, office allowances, staff salaries, travel expenses, health insurance, Secret Service protection that costs millions more. and every single one of them is a multi-millionaire many times over.

Bill Clinton has earned over $100 million from speaking fees since leaving office in 2001. He charges up to $750,000 for a single speech. His net worth is estimated at over $120 million. Yet, he still cashes his $200,000 annual pension check from taxpayers. George W. Bush reportedly earns between 100,000 and $175,000 per speech.

His net worth is estimated at $40 million. He still collects his pension. Barack Obama signed a book deal worth $65 million in 2017, just months after leaving office. He and Michelle Obama reportedly earned hundreds of thousands of dollars for individual speaking appearances. Their combined net worth exceeds $70 million. President Obama still receives his government pension and benefits.

Even Jimmy Carter, who’s genuinely lived a modest post-presidential life focused on humanitarian work, has a net worth of over $10 million. He too receives the full pension and benefits. All of this exists because President Harry Truman convinced the United States that former presidents might starve without government support, the total cost to taxpayers.

Between 2000 and 2020, these four former presidents received approximately $56 million in government benefits. not including Secret Service protection, which costs millions more annually. That’s $56 million given to men who are already extraordinarily wealthy, who could easily afford to pay their own office expenses and staff salaries.

Why? Because in 1958, President Harry Truman went on national television and told the country he was nearly broke. But here’s where the story gets even more complicated, even more morally ambiguous. Was President Harry Truman entirely wrong? Think about it from his perspective. He had refused those corporate board positions.

He didn’t lend his name to commercial enterprises the way other former presidents had done. He genuinely believed and this belief was sincere. Even if his poverty wasn’t, that there was something fundamentally corrupting about former presidents cashing in on the office. His choice to accept a government pension instead of corporate money wasn’t pure hypocrisy. It was a different kind of transaction.

In Truman’s mind, taking money from the American people through an official government program was dignified. It was proper. It was the nation honoring its former leader through legitimate channels. Taking money from corporations meant selling access, selling prestige, selling the intangible dignity of having been president of the United States.

There is a difference, even if it’s a subtle one. Even if President Harry Truman twisted the truth, and he absolutely did to get what he wanted, the real tragedy isn’t that President Harry Truman took a pension he didn’t strictly need.

The real tragedy is that he felt compelled to lie about needing it, that he couldn’t simply say to Congress, “I served the United States for 8 years during its most critical period. I made decisions that shaped the world. I believe that service should be honored with a pension just as we honor retired generals and admirals and federal judges. If he’d made that argument honestly, Congress probably would have passed the same law.

The United States in the 1950s was prosperous, generous, grateful to its wartime leaders. The idea of providing dignified retirement for former presidents was reasonable on its own merits. But President Harry Truman didn’t trust that honesty would work. He didn’t trust that the United States would reward him simply for his service.

So instead, he created a story of hardship and struggle. He weaponized his carefully cultivated reputation for integrity to extract sympathy and support from a public that believed every word he said. And in doing so, he created a monster. Today, former presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama can each earn $200,000, the equivalent of their entire annual pension, from a single 1-hour speech, to a Wall Street bank or tech company. They can sign book deals worth tens of millions.

They can join corporate boards if they choose. They can monetize the presidency in every way President Harry Truman claimed was beneath the dignity of the office. And they still collect their government pensions and million-doll annual allowances from taxpayers.

The former president’s act has become exactly what President Harry Truman supposedly fought against. A way for former presidents to have it all, to cash in on their fame and collect government money to commercialize the presidency and claim public support for their dignity. Would President Harry Truman be horrified by this outcome? Would he feel vindicated? Would he see himself as the architect of this system or as its first victim? We’ll never know.

President Harry Truman died on December 26th, 1972 at the age of 88 at Kansas City’s research hospital. He’d lived 19 years after leaving office. 19 years of comfortable retirement, funded partly by the pension he’d lobbied so hard to create.

Partly by the wealth he’d accumulated before, during, and after his presidency, his funeral was attended by dignitaries from around the world. Presidents and prime ministers eulogized him. The United States mourned the passing of a great man. His reputation had been completely rehabilitated from the dark days of 1953 when he’d left office as the most hated president in modern history.

By 1972, President Harry Truman had become a legend, a symbol of integrity and plain spoken honesty, a president who’d done what needed to be done regardless of political consequences. A man who’d stayed true to his principles even when it cost him everything. And that reputation, it was built at least partly on a foundation of lies about money.

So, here’s what we’re left with. After 7,000 words and 1 hour of storytelling, President Harry Truman was not the saint his biographers made him out to be. But he wasn’t a villain either. He was something more complicated and perhaps more interesting than either extreme.

He was a man who genuinely believed in the dignity of the presidency, but who also believed that dignity should come with financial security. A man who refused to sell out to corporations, but who had no problem manipulating Congress and the American public. A man whose integrity was real in some ways and completely manufactured in others.

A man who could be both principled and duplicitous, honest and calculating, noble and petty, sometimes all at once. In other words, President Harry Truman was exactly like the rest of us. complicated, contradictory, self-serving, occasionally heroic, frequently flawed, and trying his best to navigate a world that doesn’t always reward virtue the way we think it should.

The question we should ask isn’t whether President Harry Truman was a good man or a bad man. The question is, why do we need our presidents to be saints? Why does the United States demand that our leaders be either perfectly virtuous or completely corrupt with no middle ground? Why can’t we accept that most of them, like most of us, live somewhere in the vast gray area between those extremes? Maybe the real lesson of President Harry Truman’s poverty isn’t about his integrity or his dishonesty.

Maybe it’s about our desperate need to believe in heroes, even when the evidence suggests they’re just human beings making flawed, self-interested choices and then creating narratives to justify those choices. President Harry Truman dropped atomic bombs on two cities and never apologized.

He integrated the armed forces and destroyed his own party’s coalition. To do it, he fired the most popular general in the United States to preserve civilian control of the military. He created NATO and saved Europe from Soviet domination. These were acts of courage, vision, and moral clarity. He also lied about being poor to get a government pension he didn’t need. He manipulated public opinion.

He created a false narrative that has cost taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars over six decades. Both things are true. The heroism and the dishonesty, the courage and the manipulation, the integrity and the fraud. That’s President Harry Truman. That’s the real man behind the legend. Not the simple farmer from Missouri. Not the plain-spoken man of the people. Not the president who stayed poor out of principle.

Just a complicated human being who made history, told some lies, saved the world a few times, and wanted to be comfortable in his retirement. So, here’s my final question for you. Would you rather have a president who pretends to be poor to maintain dignity, or one who openly cashes in and admits they’re doing it? Is honesty about greed better than dishonesty about integrity? Should we even care how rich our former presidents get as long as they serve the country well while in office? Drop your answer in the comments. I genuinely want to know what you think. And if stories like this, where the heroes turn out to

be complicated and the legends turn out to be carefully constructed fictions are your thing, then hit that subscribe button, leave a like, and tell me what other historical figure should I investigate next. Because I promise you, almost everyone you think you know is way more interesting, more flawed, and more human than the history textbooks admit.