They called him reckless. They called him unpatriotic. Some even whispered the word traitor because after World War II, one American general did the unthinkable. He said openly and without apology that Germany should have won the war. His name was General George S. Patton, and what he meant was far darker, more complex, and more disturbing than most people realize.

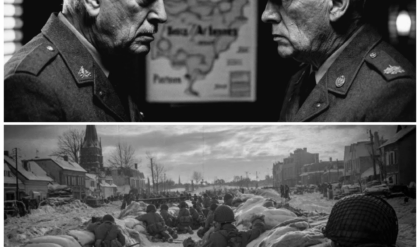

In the fall of 1945, Europe was a graveyard of broken cities. Berlin was ash. Hamburg was rubble. Dresdon was smoke and melted stone. Millions were dead. Millions more displaced. And the world tried to pretend the war had solved something. But Patton wasn’t pretending. Stationed in Bavaria overseeing occupied Germany.

He grew angry and disgusted, not with the Germans, but with the Allied leadership. His private letters, memos, and diary entries read like the writings of a man trapped in a political prison. He wrote things that could have ended his career instantly, but he said them anyway because Patton believed the Allies had made a catastrophic mistake.

He believed America had defeated the wrong enemy. Then came the sentence that shook everyone around him. In October 1945, during a meeting with British officials, Patton leaned back, stared them in the eyes, and said, “We fought the wrong enemy. Germany should have been our ally. We should have fought the real threat, the Soviets.

It wasn’t a slip. He repeated it in letters to his wife, in conversations with generals, in meetings with politicians. Patton genuinely believed Germany should not have been destroyed but preserved. He believed the war had ended in the wrong direction of history. To understand why, you have to see what Patton saw after the war.

He expected a dangerous hostile population. Instead, he found a nation terrified of starvation, shattered emotionally, and struggling simply to survive. But what alarmed him more was the rapid aggressive expansion of the Soviet Union. City after city fell under communist control. Executions began. Deportations. Elimination of anyone the Soviets considered undesirable.

Patton wrote bluntly. The Russians are the danger. We have destroyed the only nation in Europe that could have stopped them. To him, Germany wasn’t the world’s greatest villain. It was the last barrier between Europe and Stalin. Patton believed America had done Stalin’s work for him. He believed the Allies had removed the keystone of European balance and handed half the continent to a new tyrant.

And the more he watched the occupation unfold, the more convinced he became that the real enemy had not been defeated at all. Then Patton witnessed what he called the allies most self-destructive policy, denazification. On paper, it was meant to purge extremists. In practice, it removed anyone with even distant connections to the previous regime.

Teachers, engineers, doctors, administrators. 8 million Germans had once signed a party membership card. Removing all of them meant crippling the entire structure of German society. Patton compared it to punishing every American who had ever joined a political party. He warned that this policy would destabilize Germany and open the door for communist infiltration.

And he was right. Soviet agents flooded schools, councils, and newspapers. The Allies were so busy hunting former party members that they didn’t notice the silent expansion of Soviet influence. Patton called it insanity. But no one listened. By late 1945, Patton had crossed a line no American general was supposed to cross.

He wasn’t just criticizing decisions, he was questioning the legitimacy of the outcome of the war itself. He wrote that the allies had strengthened the Soviet Union, weakened Europe, and created a vacuum that would lead to the next global conflict. In his diary, he wrote, “I am being ordered to destroy the very people we should be working with.

The world is marching toward the next war, and they are too blind to see it.” Washington told him to stop, stop talking, stop writing, stop telling people that Germany should have been America’s partner instead of its enemy. But Patton did not stop. Instead, he made a choice that pushed the situation beyond the breaking point.

He refused to remove former German officials and officers from their positions in Bavaria because they were the only people capable of running the region effectively. He told Washington, “You cannot run a country with amateurs. The Germans know how to rebuild Germany. Let them.” He even allowed former German soldiers to assist American troops in maintaining order.

Newspapers back home erupted. Politicians demanded his removal. Some wanted him court marshaled. Patton said privately. I am being punished for telling the truth. They destroyed Germany to hand Europe to Russia and they will not admit it. Washington decided he had to be removed before he spoke publicly and created a political firestorm.

In late 1945, Patton requested permission to return to the United States. He planned to make a major public statement. He told a friend, “When I get home, I’m going to tell the American people exactly what is happening in Europe.” He intended to expose the political games, the Soviet manipulation, the failures of Allied policy, and the reason he believed America had fought the wrong enemy.

It would have changed everything. But he never made it home. On December 9th, 1945, Patton’s car was involved in a strange low-speed collision outside Mannheim. He was the only person seriously injured, the only one paralyzed, the only one who didn’t recover. He died 12 days later. Officially, it was a tragic accident.

Unofficially, many have wondered whether a general who openly defied Washington challenged the purpose of the war and planned to go public with explosive information was simply too dangerous to let speak. When Patton said Germany should have won, he wasn’t praising ideology or atrocities. He wasn’t defending a regime.

He was talking about geopolitical balance. He believed the Allies had shattered Europe’s equilibrium and empowered a far greater threat, the Soviet Union. He believed that by destroying Germany completely, the Allies had guaranteed decades of conflict, tension, and division. And he believed he was witnessing the birth of a new world order that would lead directly into the Cold War.

Looking back, Patton wasn’t wrong about the Soviet Union. He wasn’t wrong about the future of Europe. He wasn’t wrong about the war that would follow. He saw the next conflict long before anyone else did. And he feared only one thing, a world that refused to see what he saw. So when he said Germany should have won, he wasn’t praising a nation.

He was warning a world.