- A secret facility hidden in the English countryside. British engineers stood around a workbench covered in lumps of coal. Except these were not lumps of coal. They were bombs. Weapons designed to look so perfectly ordinary that German soldiers would shovel them directly into locomotive fireboxes without a second thought.

The moment that fake coal hit the flames, it would detonate, rupturing the pressurized boiler and transforming an entire train into twisted metal. No evidence, no warning, just another mysterious explosion that German investigators would chalk up to equipment failure. This was SOE, explosive coal, and it would turn Germany’s own fuel supply into a weapon against them.

To understand why British intelligence needed fake explosive coal, you have to understand how completely Nazi Germany depended on railways. By 1941, German forces had conquered most of Europe. They controlled territory stretching from the French Atlantic coast to the gates of Moscow. And they moved almost everything by train, troops, tanks, ammunition, food, fuel.

The Deutsche Riceban and captured railway networks were the arteries keeping the German war machine alive. Road transport consumed precious fuel that Germany could not spare. Railways consumed coal, and coal was everywhere. This dependency created a vulnerability. Destroy enough locomotives and you German logistics.

But locomotives were tough targets. Track could be repaired in 24 hours. Bridges were heavily guarded and conventional sabotage required resistance fighters to get close to railway infrastructure, plant explosives, and escape before German patrols discovered them. Many died trying. The British needed something different.

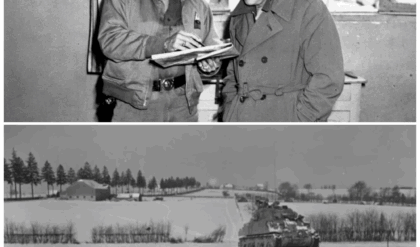

Something that required no technical expertise from resistance networks. Something that could be planted by anyone with access to a coal pile. something that would destroy locomotives from the inside. The solution came from SOE research stations hidden across Hertfordshire. Station 12 at Aston House near Stevenage served as the primary production facility.

It had been relocated there from Bletchley Park in November 1940 after explosives testing disturbed the codereers working next door. Under Colonel Leslie Wood, station 12 became SOE’s main weapons factory. During the war, it produced 12 million time pencil detonators and over 38,000 limpet mines.

But among its most ingenious products were explosive devices disguised as ordinary lumps of coal. The technical challenge was deceptively complex. The device needed to look exactly like real coal. It needed to survive being thrown onto coal piles, shoveled into tenders, and handled by workers without detonating prematurely.

But it also needed to explode reliably when it entered a firebox. British engineers solved this with a combination of plastic explosive and clever camouflage. Each device contained approximately one quarter pound of Nobel 88 plastic explosive. This was a green plastic-ike substance with a faint almond odor developed by Nobel Chemicals Limited specifically for sabotage operations.

The explosive was paired with a number 27 detonator and a heat sensitive fuse. When the disguised coal entered a locomotive firebox, intense heat would ignite the fuse, triggering the detonator and main charge. One quarter pound of plastic explosive alone would cause serious damage. But the real destruction came from secondary effect.

The explosion would rupture a steam boiler operating at several hundred lb per square in of pressure. The entire locomotive would tear itself apart. Production methods evolved through three distinct phases. The earliest technique involved drilling actual lumps of coal with a 6-in serrated tube, filling the cavity with explosive and detonator, then concealing the hole with coal dust and glue.

Laboratory assistant Arthur Christy conducted these early experiments at station 12. He later described inserting about a quarter pound of PE into drilled coal lumps, but this method proved fragile. Coal would often disintegrate under drilling pressure. Station 15 at the Thatched Barn in Borumwood revolutionized production.

This facility housed SOE’s camouflage section under Lieutenant Colonel Elder Wills, a pre-war film art director. He recruited over 300 film production workers, prop makers, and craftsmen. Among them was Wally Bull, who would later work on 2001 A Space Odyssey. Bull developed molded explosive coal using dyed herculite plight plaster coated with real coal dust.

These clam shell designs eliminated the fragility problems of drilled coal. The final refinement encased the explosive charge in metal with liquid plaster poured around it, eliminating visible seams entirely. Both explosive and incendry variants were produced in multiple sizes designed to match different coal types. Ligignite appears brown.

Anthraite is nearly black. Bituminous coal shows various lusters. SOE manufactured versions matching each type so devices would blend seamlessly with local fuel supplies across occupied Europe. Between 1941 and 1945, SOE produced approximately 3 12 tons of explosive coal. At roughly one quarter pound per device, this suggests somewhere between 6,000 and 14,000 individual weapons.

Distribution relied on RAF special duty squadrons based at RAF Tempsford. Number one 38 squadron and number 161 squadron flew Halifax, Sterling, and Lander aircraft on supply drops across occupied Europe. By war’s end, these squadrons had flown over 13,500 sorties, delivering more than 10,000 tons of supplies to resistance networks.

The French resistance received the largest share. SOE sent 470 agents to France between 1941 and 1940. Four, Belgium, Norway, Poland, and Yugoslavia all received explosive coal shipments. Yuguslav partisans under Tito found the weapon particularly valuable given their constant attacks on German railway supply lines.

If you’re finding this deep dive into British sabotage technology interesting, consider subscribing. It helps the channel and means you will not miss the next one. Here is where the story becomes complicated. Despite 3 and 1/2 tons produced and distributed across occupied Europe, documented records of specific explosive coal attacks remain remarkably sparse.

No named operations, no specific dates and locations, no confirmed locomotive kills appear in declassified sources. This absence requires explanation. The weapon was designed to leave no evidence of sabotage. A successful attack would appear as an accidental boiler explosion, impossible to attribute to enemy action. German investigators finding wreckage would see equipment failure, not sabotage.

That deniability was the entire point. If explosive coal worked as intended, successful attacks would be historically invisible. Many S SOE records were deliberately destroyed after the war or remain classified 80 years later. Railway sabotage in occupied Europe was so extensive that attributing specific damage to any particular method proved impossible.

The French resistance conducted over 1,800 locomotive attacks between June 1943 and May 1944 using every available method. Explosive coal was one weapon among many. What we can document is the psychological impact. Once word spread that coal piles might contain hidden bombs, Germany faced an impossible choice. Accept random catastrophic explosions in locomotives, ships, and factories, or redeploy thousands of troops away from combat duties to guard coal supplies across occupied Europe.

Neither option was acceptable. Accepting the risk meant unpredictable equipment losses and terrified crews. Guarding coal meant withdrawing forces from an already overstretched military. The Germans understood this threat because they developed their own version. In June 1942, Operation Pastorius landed eight German Abare saboturs on American beaches.

They carried plastic explosives molded to resemble coal alongside TNT and fuses. Their targets included coal fired power plants and railroad infrastructure. All eight were captured before executing any attacks. Germany never attempted similar operations against the American mainland again. The British double agent Eddie Chapman, codeen named Agent Zigzag, provided direct evidence of German capabilities.

In March 1943, his Abbeare handlers gave him two German manufactured coal bombs to sabotage the merchant ship City of Lancaster. Chapman immediately handed the devices to the ship’s captain, who passed them to MI5 for analysis. The episode revealed that German coal bomb construction lagged British innovation.

The Germans were still drilling real coal while SOE had moved to sophisticated molded designs. American adoption demonstrates the concept’s value. The OSS research and development branch under Stanley Levelvel developed an American version cenamed Black Joe. It used 60/40 pentalite rather than Nobel 88.

OSS went further with a specialized coal camouflage kit containing paints, brushes, and tools, enabling agents to match explosive coal to local varieties. Both organizations recognize the weapon’s potential, even if documented results remain elusive. The broader railway sabotage campaign achieved devastating results through combined methods.

French resistance attacks achieved 60% reduction in rail traffic from March to June 1944. 486 attacks around D-Day prevented German reinforcement of Normandy. In Yugoslavia, maintaining rail transport required what one German general called enormous problems and heavy railroad security, tying down at least half of the armed forces.

Transfer to train security detail became so hazardous it was used as severe punishment. Whether explosive coal contributed significantly to these numbers matters less than whether it contributed to the climate of fear and resource strain that characterized German occupation. Contemporary documents emphasize that destroying locomotives specifically inflicted disproportionate damage compared to cutting track.

Track could be repaired in days. Locomotives required months of factory work to replace. The concept’s influence extended beyond 1945. CIA historical reviews note that given the importance of coal to economies on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Future historians may need to explore how explosive coal featured in the covert struggles of the Cold War, the weapon pioneered what became standard doctrine for disguised explosives.

Dead rats stuffed with PE for factory furnaces. Explosive logs. Landmines disguised as animal dung. Modern improvised explosive devices concealed in everyday objects trace their lineage to Station 15’s innovations. Surviving examples reside in the Imperial War Museum, including 16 mm test footage filmed by Ceil Clark at station 17.

The International Spy Museum in Washington and the Museum of World War II in Massachusetts also hold specimens. 1942, a secret facility in the English countryside, British engineers created a weapon so elegant that its successes remain historically invisible. So psychologically devastating that Germany developed copies despite having no defense against the original.

3 and a half tons of explosive coal manufactured. Thousands of devices distributed to resistance networks across occupied Europe. An unknown number of locomotives destroyed in explosions that German investigators attributed to equipment failure rather than sabotage. SEE explosive coal represents unconventional warfare at its most sophisticated.

A weapon measured not in confirmed kills, but in fear, in resources diverted, in the fundamental uncertainty injected into every coal pile across Nazi occupied territory. British engineers solved a problem others had not even identified. They turned Germany’s dependency on coal into a vulnerability. And they did it with a quarter pound of plastic explosive hidden inside fake rocks that German soldiers shoveled into their own fireboxes. That was British engineering.

That was SOE. And that was how fake coal helped destroy the Third Reich from the inside.