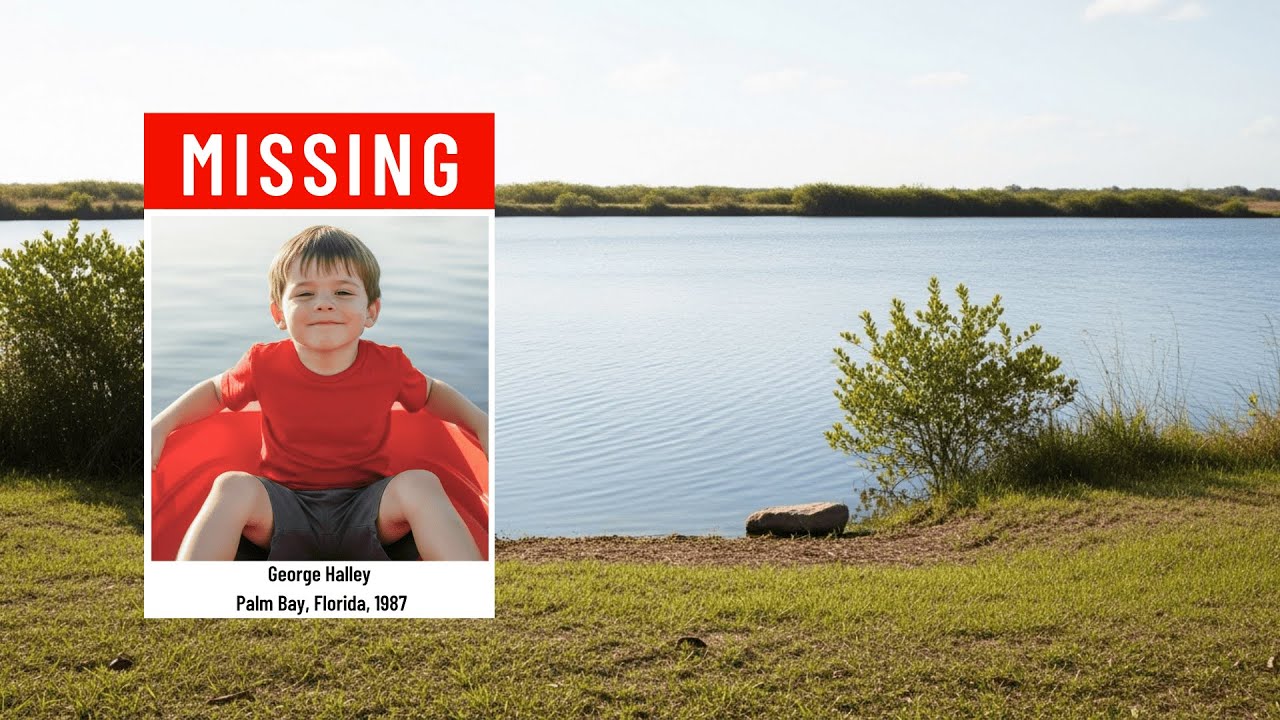

Boy Vanished in 1987 — 18 Years Later, a DNA Test Reveals This…

It began on a quiet summer afternoon in Palm Bay, Florida in 1987. A family trip by the lake, sunlight on the water, a boy’s laughter echoing through the trees. Then, in the span of a heartbeat, the sound was gone. No splash, no scream, no trace. Only a small red boat drifting toward the reeds, its rope untied.

For days, search teams combed every inch of Silverpine Lake, but the water gave nothing back. How does a child vanish in plain sight? And where does the silence go when no one can explain it? The Halley family lived in Palm Bay, a small town built between Flat Pinewoods and the Wide Atlantic. Mark Howie, 35, worked as an electrical engineer for the local power company.

He was steady and methodical, the kind of man who checked every lock twice before bed and marked appointments on the same wall calendar each year. His wife, Carol, taught music at an elementary school. She had a soft voice and an old piano in their living room that she played in the evenings, her tunes drifting through the house like something fragile.

Together they had one son, George, born May 1981, who filled their quiet home with the soft noise of questions. George was six that summer, a small boy with brown hair that turned gold in sunlight. His mother said he could sit still for hours if there was water nearby.

He liked to line up pine cones, collect leaves, and fold paper boats that he would launch in puddles after the rain. Neighbors often saw him sitting on the curb, tapping his fingers on his knees, staring at the clouds as if he was waiting for them to speak back. He wasn’t shy, but he was quiet, the kind of child who listened more than he talked.

That July, Mark decided to take the family camping at Silverpine Lake, a secluded park 2 hours north of Palm Bay. He wanted his son to see the lake he had visited as a boy. A lake surrounded by tall pines that gave it its name. It wasn’t a tourist resort, just 20 camping spots, one small dock, and a gravel road that curved around the water.

For families like the Halls, it was a simple escape. Cheap, close, and calm. They left early on Saturday morning, July 18th, 1987. The weather was clear, around 88° with a steady southern wind. Carol packed sandwiches, a cooler of lemonade, and a small portable radio. George held tight to a red plastic boat, his new favorite thing.

Mark had bought it just a week earlier at the hardware store, saying, “Every boy needs something that floats.” It was small, made for shallow water near shore, and came with a nylon rope for safety. They reached Silverpine by late morning. The campground was half full. Families cooking, kids skipping stones, a few men fishing from the dock. The lake itself was quiet, smooth like glass, with reflections of the pine trees shimmering across its surface.

They chose a spot close to the water between two other campsites and pitched their tent. Mark tied the red boat to a wooden stake just a few feet from the edge. He tested the rope twice before letting George climb in. “You can sit inside,” he told him, “but don’t untie it unless I’m here.” The boy nodded. Carol smiled, taking a picture of them with her camera.

“Mark kneeling, the boy in his red shirt sitting proudly inside his small boat, water glimmering around them. The rest of the day passed slowly. Around noon, they ate sandwiches and chips under the shade. Other campers radios played country songs. The air smelled of grilled meat and sunscreen.

Mark took the boat out once, rowing in a short circle close to shore while George laughed at the splash of oars. They came back within minutes. Nothing unusual, nothing remarkable, just a family enjoying a calm summer afternoon. At around 300 p.m., Carol left for the restroom up the path about 200 ft away.

Mark stayed behind, unpacking firewood from the car and preparing for dinner. George sat on the shore, poking the wet sand with a stick, the red boat bumping lightly against the water line. The sun reflected sharply off the lake. The only sound was the soft tap of rope against wood. At approxima

tely 3:45 p.m., according to later police records, Mark turned to place a bundle of wood near the tent. When he looked back, less than 2 minutes later, the boy was gone. The space where George had been sitting was empty. The rope that held the boat was loose, drifting in the shallow water. The small red boat was floating 10 or 15 ft from shore, unmanned. Mark called out once, then again louder.

George. No reply. He waited into the water, pulled the boat back, and looked around. There were no footprints leading into the trees, no splash marks, no cry for help. The ground was soft but undisturbed. The air was still. He ran up the trail toward the restroom, calling for Carol.

When she appeared confused and carrying a towel, he pointed to the empty shoreline. He was right there, he said. I just turned around for a second. Carol’s face went white. Together, they searched the nearby area, the tent, the parking lot, the picnic tables. Nothing. By 4:10 p.m., other campers joined the search. A fisherman crossed the dock to help. A woman ran to the ranger station to call for authorities.

The Halley parents kept circling the same 50 yards of shore, voices cracking. One camper said he’d seen the boy earlier sitting by the boat, but nothing after that. No one had heard a scream, no splash, no car leaving the park. At 4:30, a park ranger arrived. He asked Mark to stay put while officers combed the woods.

Within the hour, deputies from the Lake County Sheriff’s Office reached the site. They taped off the immediate area, marking footprints, tire tracks, and distances with yellow stakes. Witnesses were asked to remain for statements. Divers were requested before sunset. Carol sat by the picnic bench holding George’s blue towel. Mark refused to sit.

He kept walking from the tent to the lake and back again, repeating the same sentence under his breath. He was right there. Around 6, the divers entered the water. The lake’s center was only about 12 ft deep, visibility low, the bottom layered in weeds. They searched in slow, measured sweeps, but found nothing. No clothing, no sign of struggle, not even a dropped toy.

Above the water, the campground had gone silent. The other families watched from a distance, their fires unlit. At sunset, the red boat sat upside down on the sand. Its rope was cleanly untied, not torn. The wind had shifted inland, meaning anything a drift should have come toward the shore, not away.

The ranger noted the details, writing them into his small notepad, while the sheriff ordered the area to be closed overnight. By 9:00 p.m., flood lights were set up along the dock. Helicopters flew low once before returning to the nearest airfield. Dogs traced the scent around the edge of the camp, but every trail stopped at the same place, the water’s edge. Carol refused to leave.

She sat by the lake through the night, her eyes fixed on the dark surface. A deputy offered her a blanket, but she didn’t respond. Mark stood beside her, silent. The lake was perfectly calm, reflecting the lanterns in thin, trembling lines. When dawn came, the search resumed. Boats fanned out in every direction. Volunteers moved through the forest with long sticks, proddding the ground.

Reporters began to arrive, taking pictures from behind the police line. The air smelled of damp pine and gasoline, but the water remained empty. And from that afternoon in July 1987, no one ever saw George Halley again. By dawn the following morning, Silverpine Lake was no longer a quiet campground, but a scene sealed by yellow tape.

The air smelled faintly of gasoline and pine needles as patrol cars lined the dirt road. Deputies from the Lake County Sheriff’s Department moved with quiet precision, their boots sinking into the soft sand. The search had entered its second day, and what began as a family emergency was now a coordinated investigation. Sheriff Raymond Cole took charge.

A man seasoned by years of missing person calls that almost always ended with recovery. But this one felt different from the start. He ordered a perimeter set up across the lake’s eastern bank and assigned two officers to document the entire campsite. The tent, the picnic table, and the narrow strip of shore where the red plastic boat had been tied. By 6:30 a.m.

, the first helicopter arrived, hovering low, its blade scattering mist across the water. On the ground, rescue divers suited up beside the dock, checking oxygen tanks and ropes. The sheriff watched silently, arms folded. The operation had drawn nearly 40 people, search and rescue teams, volunteer firefighters, and local rangers.

Everyone believed the same thing at first, a simple accident, a small child lost beneath the water. But as the morning unfolded, the scene refused to fit that explanation. The area around the stake where the boat had been tied was examined carefully. No signs of struggle, no deep impressions in the sand, no drag marks suggesting the boy had slipped or been pulled in.

The rope itself was dry and cleanly untied. The end slightly curled as if released by hand rather than torn or cut. Technicians dusted for prints, but the only identifiable ones belonged to Mark Halley, the father. Divers entered the lake at 7:15. The water was clear for about 2 ft, then turned dark with mud and weeds.

They moved in a slow arc pattern, marking off every 10 yards. On the surface, deputies followed their path from inflatable boats, watching for bubbles. After 2 hours, the divers came up empty. No clothing, no body, not even a sign of air pockets caught beneath branches.

At the sheriff’s request, the weather office in Orlando sent over the previous day’s wind data. The report showed steady gusts from the south blowing toward the shore. That single detail changed everything. If George had fallen into the lake, his body and the small red boat should have drifted closer to land, not farther away. The logic didn’t hold. Something else had to explain why the boy and the boat had separated.

By midm morning, the press began to arrive. Local news vans parked along the dirt road. Reporters standing behind police lines with microphones and bright smiles that didn’t match the mood. They called it a tragic accident at Silverpine Lake. Their voices carrying through the trees. The sheriff gave one statement only.

The child was missing. The search was active and all leads were being followed. Inside the command tent, detectives questioned the halls separately. Mark’s answers were measured, his tone flat from exhaustion. He repeated the same timeline. How George had been sitting by the water, how he had turned to stack firewood, and how the boat had drifted away.

Carol’s voice shook as she spoke, but her account matched her husband’s in every essential detail. The investigators found no inconsistencies, no sign of deceit, no motive that could point inward. After the interviews, Carol was escorted back to a temporary rest area where paramedics gave her water.

She kept her eyes fixed on the lake the whole time, whispering her son’s name like a prayer. Around noon, a new team of rescuers arrived with additional equipment. The sheriff authorized the use of sonar imaging to scan deeper sections of the lake. The machines were old and imprecise, but even their fuzzy outlines showed no large objects beneath the surface. “If he’s down there,” one operator said quietly, we’d see something.

The search expanded outward. Deputies walked the surrounding woods, checking underbrush, drainage ditches, and animal dens. They examined every vehicle that had left the campground the previous day. Not one witness reported seeing a stranger, a child running off, or a vehicle departing in haste. The case, for the I moment, had no direction.

By the afternoon, the sheriff gathered his core team under the shade of a pine tree. “We’ve got nothing,” one detective admitted. “Not a footprint past the waterline, not a scrap of fabric, nothing floating.” Cole rubbed his chin and stared out at the lake. “Then he didn’t walk away,” he said, and the lake didn’t take him. “So, where is he?” It was a question no one could answer.

The only tangible piece of evidence, the red plastic boat, was tagged and photographed. Its hull bore faint scratches from rocks near the shore, but no signs of damage. The seat was dry, which suggested it hadn’t capsized. The rope attached to the bow was roughly 3 ft long, and the knot at its end had been pulled free cleanly, as if by deliberate hands.

Forensics took samples, though the likelihood of Prince surviving on that surface was slim. As daylight faded, the operation slowed. Deputies remained stationed along the shoreline, lanterns ready for the night shift. A soft breeze rustled through the trees, carrying the faint sound of frogs from the far bank.

The water itself looked harmless, smooth, quiet, indifferent. The sheriff gave his final instructions for the evening. “We’ll keep the divers ready until midnight,” he said. “After that, we scale down until sunrise.” He paused before walking back toward his car. “Keep eyes on the parents. They’re the only ones who saw him last.

” That night, reporters broadcast live from the road outside the park. Their stories painted the same picture. A six-year-old boy presumed drowned while playing near the water. It was the simplest version and perhaps the one the public wanted to believe. But in the sheriff’s office, the working theory was less certain.

The following morning, July 20th, deputies reviewed all reports. Weather confirmed calm conditions. No storms, no currents strong enough to pull anything into the center of the lake. The case file filled with notes that contradicted one another. Too few signs for a kidnapping. Too clean for an accident. At 9:00 a.m., Sheriff Cole signed the temporary classification himself.

Accidental drowning. Body not recovered. It was, for the record, a placeholder. He closed the folder and looked once more at the photograph clipped to the inside cover. a boy with brown hair squinting in the sun, holding a red plastic boat. The official search would continue for several more days, but in truth, the moment he signed that page, the case had already begun to drift toward silence.

And in the report’s final line, written in blue ink that had slightly bled through the paper, he added six words that summarized the entire investigation so far. No witness, no struggle, no body. When the official search ended, Silverpine Lake fell quiet again. The rangers packed away their tents and buoys. The last rescue boat left just before dawn on July 27th, 1987.

For weeks after, locals drove by to look at the taped off entrance, whispering as if the place itself might hold the answer. But there was nothing more to see, just still water, a few wilted flowers left by strangers, and the hollow echo of a child’s name that no longer carried across the wind.

The Holly family returned home that week. Their neighbors brought casserles, offered prayers, said all the things people say when words aren’t enough. Mark barely responded. He went back to work at the power company after 3 weeks, but co-workers said he stared through them, doing his job in silence. Carol stopped going to church.

She sat at the piano some evenings, pressing the same note again and again until her fingers went numb. On her classroom wall, the seat where George’s picture had hung was left blank. The sheriff’s office kept the file open for 3 months before closing it under the label presumed accidental drowning. Body unreovered.

It was not a verdict, only a placeholder for a truth that refused to show itself. The red boat remained in evidence storage, tagged and sealed in plastic. It was the only physical trace left of the day the lake went still. In the following months, rumors spread. Some said a drifter had been seen nearby. A man with a pickup truck who vanished the same weekend.

Others spoke of sink holes or hidden currents at the lake’s center. The sheriff checked each claim, but none held weight. By winter, the calls stopped. The town moved on, but Carol did not. Each year on George’s birthday, she mailed a letter to the Lake County Sheriff’s Office asking if there had been any news.

The replies were always the same. No new information at this time. By 1990, her handwriting had grown shaky and her letters shorter. Mark tried to believe what the report said. He told himself their son had fallen, that the water had simply taken him somewhere unreachable. But some nights when he couldn’t sleep, he would drive back to Silverpine, sit by the gate, and stare at the line of trees.

The lake had been closed to the public since 1989 due to low attendance and funding cuts. The wooden dock had started to rot, boards pulling loose one by one. The red no entry sign faded under the Florida sun. In 1992, the case briefly flickered back to life. A new deputy named Frank Rhodess had been assigned to review unsolved files for the county.

He reopened the Silverpine folder after finding it listed under unresolved child disappearances. He drove to the lake with a partner, surveying the area where the Halley campsite had once been. The dock was gone, replaced by weeds. That same week, a local hunter reported finding small barefoot prints along a creek bed about 15 miles north of Silverpine.

The deputy followed up immediately, comparing the impressions to photos of George’s shoes from the old file. The prince matched a child’s size, but not his stride or age. They belonged to a local boy who had wandered off during a camping trip. Another false lead. Deputy Roads made one final note before closing the folder again. Case inconclusive.

No evidence of death or abduction. Recommend retention in active cold file. By then, the Halleys had left Palm Bay. The house on Larksburg Drive was sold to a young couple who never knew its story. Carol and Mark moved separately. She to her sister’s home in Jacksonville. He to a small apartment near Orlando.

They didn’t divorce right away, but by 1994, the distance between them was permanent. Grief had become a third presence in their marriage, silent but heavy, filling every space between words. In 1996, a storm swept through central Florida, tearing down trees and flooding the Silverpine area. When rangers returned afterward, they found the campground half destroyed.

The dock had collapsed into the lake and several old cabins had been crushed by fallen pines. The county decided not to rebuild. Silverpine was officially decommissioned that year. What remained of the lake became private property, fenced and overgrown. Still, the case lingered. Every few years, a journalist researching Florida’s unsolved mysteries would stumble upon the name George Howie. A short article might appear in a weekend edition.

Boy lost at lake still unfound after 10 years. Readers would glance at the headline, shake their heads, and move on. The world had plenty of mysteries. This was just one more that refused to resolve itself. In the archives of the sheriff’s office, the evidence box sat untouched on a metal shelf.

Inside the red boat, the rope coiled neatly, a plastic bag containing a few grains of sand. The note attached to the file read simply, “Do not destroy.” The year 2000 came quietly. Technology was changing. Florida’s small departments began converting records to digital form. Old missing person files were scanned, cataloged, and stored in statewide databases.

When the Silverpine case was uploaded, it was automatically linked to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. A black and white photo of George’s six-year-old face appeared in their archives, later converted into an age progression sketch, a digital approximation of what he might look like at 20. The artist’s rendering, while skillful, was distant and uncertain.

It showed a young man with the same eyes, but an older expression caught somewhere between life and memory. Carol saw it once on a news segment and turned the TV off before it finished. For detectives, the file remained what it had always been. A question without an answer. The data was too clean. The scene too calm. If it had been a kidnapping, there should have been tracks or witnesses.

If it was a drowning, there should have been a body. And yet, there was nothing. No trace of life, no sign of death, only absence. Some investigators whispered over the years that the boy had been taken by someone familiar, someone who knew the routine, who had been close enough to untie the rope and slip away unnoticed.

But there was never a name, never a suspect, never even a theory that could hold under scrutiny. By 2004, 17 years had passed. Sheriff Cole had long since retired. His hair turned white. The file he once kept on his desk had been transferred to the cold case cabinet, stored alphabetically, among dozens of others.

Once a year, interns reviewed it as part of a training exercise. They’d read the timeline, shake their heads at the lack of leads, and move on. To them, the story belonged to another time. A time before surveillance cameras, before databases, before the word closure became a demand instead of a wish.

In Palm Bay, few remembered the Halley name anymore. The lake itself had become private property, its edges fenced off by the new owners. Locals who drove past at night swore they could still see the faint glow of lanterns across the water, the ghost of the search that never found what it was looking for.

And somewhere in a storage room cooled by humming fluorescent lights, the file sat waiting, paper turning yellow, photographs fading, the small red boat sealed in plastic. 18 years had passed since a six-year-old boy vanished in the quiet heart of Florida. The world had moved on, but the evidence never had.

It stayed still, as if holding its breath, waiting for something. a mistake, a coincidence, a fragment of truth to bring it back to life. No one knew that the spark would come not from the lake or from memory, but from a single drop of blood. 18 years had passed since the boy vanished from Silverpine Lake. The file sat dormant in a metal drawer, its pages yellowed and corners curled from humidity.

For the Lake County Sheriff’s Department, the case of George Howie, missing child, 1987, had become a formality, one among hundreds of unresolved disappearances from the 1980s. No new leads, no sightings, no phone calls, only the same questions echoing in silence. But in March of 2005, more than 800 miles away, a quiet chain of events began that would draw the name George Halley back into the light.

It started at a blood drive in Columbus, Ohio. A software engineer named Michael Avery, 24 years old, stood in line with his co-workers in the lobby of a technology firm. It was a companywide event. free t-shirts, snacks, and a photo on the office bulletin board for everyone who donated. Michael signed his name, rolled up his sleeve, and joked with the nurse about being afraid of needles.

The process took 15 minutes. He drank orange juice, took a cookie, and went back to his desk. The blood drive ended by noon. Boxes of samples were sent to a regional processing center where as part of standard procedure, donor DNA profiles were temporarily logged into a federal cross-check system.

The combined DNA index system or COTUIS. The purpose was medical and logistical, not investigative, but sometimes the system recognized a pattern it wasn’t designed to find. That night, Aziosoy computer flagged a match, a near perfect genetic alignment between the new donor sample and an archived DNA profile from the National Missing Children database.

The file had been dormant for years, attached to the name of a six-year-old boy last seen in Palm Bay, Florida in 1987. The system labeled it full match probability identical. At first, the technician assumed it was a clerical error. Old data, degraded samples, mismatched records. Such things happened often enough.

She reran the analysis twice. The same result appeared both times. She contacted her supervisor, who contacted the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. Within 48 hours, the Lake County Sheriff’s Office received a formal notice. DNA match, possible identification of missing person, George Howie.

The sheriff on duty that spring was not Raymond Cole, but a younger man named Daniel Ruiz, who had taken over the department after Cole’s retirement. Ruiz had been a rookie deputy in 1987. He remembered the lake, the red boat, the empty shoreline. The message landed on his desk like a ghost from another life. He read it twice before calling the state lab.

The voice on the other end confirmed the finding. The probability of error was less than one in a billion. Michael Avery, aged 24, was a genetic match to the missing child last seen 18 years earlier. At first, Ruiz didn’t know how to feel. The name meant nothing, but the number, the year, brought everything back.

the search lights on the lake, the mother’s screams, the unanswered questions. He reactivated the old file, called the evidence room, and requested the sealed samples from 1987. The original DNA reference from Mark and Carol Howie, stored for decades, was retested. The results were identical. The blood from Ohio belonged to their son. The next step was verification.

Florida investigators reached out to Ohio authorities who in turn contacted the young man listed as Michael Avery. They found him easily. He lived in a modest apartment downtown, paid his taxes, and had no criminal record. By all accounts, he was ordinary, a hard-working man with a quiet manner and few close relatives.

When detectives from Columbus arrived to speak with him, Michael appeared more confused than concerned. He agreed to answer questions, thinking it was some mixup with his donation form. The conversation began simple. Birthplace, family, documents. But each answer only deepened the mystery. Michael’s official birth certificate listed him as born in 1983 in Albany, New York.

His mother was named Linda Avery. His father was unknown. When asked for hospital records, he said they had been lost in a house fire when he was a child. He had no photographs of himself before age nine. His earliest memory, he said, was of living in upstate New York in a small yellow house with his mother.

When told that his DNA matched a missing child from Florida, he laughed nervously. “That can’t be right,” he said. I’ve never even been to Florida. But when detectives showed him an aged photo of George Hley, a boy with brown hair and a red shirt standing near a lake, his expression faltered. “I don’t remember that,” he whispered. “But that boat looks familiar.

” Within a week, the Florida and Ohio departments coordinated a joint investigation. “Linda Avery, now in her 50s, was brought in for questioning. She lived in a quiet neighborhood outside Syracuse, working part-time at a pharmacy. When asked about her son’s early years, she repeated the same story. She had adopted him informally from a friend who couldn’t keep him sometime around 1992.

There were no legal papers, no court filings. It wasn’t official, she said. But he was mine. Investigators pressed her on details. Who was the friend? Where had the exchange taken place? She hesitated, then said she couldn’t remember the name. The man had told her the child’s parents had died in an accident. He needed someone to care for the boy temporarily, and she had agreed.

He gave her a box of clothes, a few toys, and a small backpack with the initials GH stitched inside. Detectives searched her home that same day. In a box stored in the attic, they found a pair of small sneakers, a faded photo of a child on a beach, and a paper tag with the name Halley written faintly in pen. All items were collected and sent for testing.

DNA from the shoes insoles matched the same sample from the 1987 case. It was enough for the state to act. The Lake County Sheriff’s Office formally reopened the Silverpine investigation as a criminal case, suspected child abduction and identity concealment. When the news broke, it spread fast. Headlines read, “Missing Florida boy found alive after 18 years.

” The story appeared on every major network painted as a miracle. A lost child rediscovered through science. But behind the headlines, investigators were less certain of what kind of miracle it truly was. Linda Avery was taken into custody for questioning, though she was not charged immediately. Michael, meanwhile, was left reeling. He spent hours with detectives trying to recall anything from before New York, any scent, sound, or image.

The only thing he could remember, he said, was water. Sometimes I dream I’m sitting in a boat, he told them. There’s sunlight on the water, then it goes quiet. In Florida, Sheriff Ruiz met with Mark and Carol How for the first time in nearly two decades. They were older, fragile, their hair gone gray. When he told them the news, Carol pressed her hand to her mouth. Mark asked only one question. “Are you sure?” Ruiz nodded.

100%. That night, the sheriff opened the old evidence box for the first time in years. Inside lay the red boat, its color faded, but still intact, and the rope coiled beside it. He placed the box on his desk and stared at it for a long time.

Stu, object that had once symbolized a loss, now represented a return, a beginning to a story that had never truly ended. Still, questions lingered. Who had taken George? How had he ended up with Linda Avery? And what had happened in the hours after he vanished from Silverpine Lake? Those answers would take months to unravel. But for the first time since 1987, the case was alive again.

The boy who vanished had a name, a face, and somewhere in his blood, the truth that refused to stay buried. The week after the DNA match became public, the story spread across the country. For the first time in nearly two decades, the name George How appeared in headlines again, this time next to the phrase found alive.

Morning shows called it a miracle. Talk radio hosts debated the science. But in the Lake County Sheriff’s Office, the excitement faded fast. The truth was only beginning to surface, and it was heavier than the story the world wanted to hear. Detectives from Florida and Ohio formed a joint task force.

Their focus was simple on paper, but nearly impossible in practice. Reconstruct 18 missing years from nothing but fragments. At the center of it all was Michael Avery, an adult who had lived an entire life under a name that wasn’t his, carrying memories that didn’t line up with his birth records. When the investigators asked for details about his early life, Michael struggled.

His first clear memory, he said, was sitting in a kitchen with yellow walls, the smell of salt, and something burning. A woman’s voice calling him Mikey. a window with condensation running down the glass. “I always thought that was just childhood,” he said quietly. “Now I don’t know if it was even mine.

” The woman he called mother, Linda Avery, was held for further questioning. She refused a lawyer at first, confident that her story, an informal adoption, no paperwork, no harm, would clear her name. She repeated that a man had approached her in 1992 saying he needed someone to care for a child whose parents had died. He looked like someone from the military, she said. Short hair, calm, polite.

I thought he was doing something good. Detectives pressed her for a name. She hesitated, then said she remembered only Frank. No last name, no phone number, just a meeting near a gas station outside Jacksonville. He gave her a box of clothes, told her to call the boy, Michael, and left. She claimed she never saw him again. To most detectives, that story sounded rehearsed, but Ruiz and his team didn’t dismiss it outright.

They began searching records from the early 1990s for any man fitting that vague description. Ex-military, transient, no fixed address. It was like chasing a shadow until an old employment file surfaced from a construction company near Ocala. The name on it, Frank Dalton. The job record was brief. 3 months in 1987, then nothing.

No tax filings, no social security updates, no trace after that year. The year George disappeared. Detectives pulled Dalton’s personnel file. The attached photo showed a man in his 30s with short brown hair and a scar over his right eyebrow. His address at the time placed him less than 30 miles from Silverpine Lake. That name reappeared 2 years later in a Jacksonville rental log.

Paid in cash, one occupant, no forwarding address. The handwriting on the form, when compared with the note found inside Linda Avery’s attic box, matched perfectly. The loop of the F, the slant of the T. For investigators, the pattern was undeniable. Whoever Frank Dalton was, he had taken the boy from Florida and handed him to Linda Avery 5 years later.

The gap between 1987 and 1992 was still missing, but the outline of a deliberate abduction had begun to take shape. When confronted with the evidence, Linda’s composure cracked. She admitted that Frank had visited her twice after the adoption, once in 1994 and again in 1996. “He came to see how we were doing,” she said. He brought money. He said it was to help me raise the boy.

When asked if she’d ever questioned him about the child’s origins, she lowered her eyes. I didn’t want to know. The financial records confirmed two unexplained deposits into her account during those same years, both from outofstate banks that later closed. Each deposit was just under $5,000. Ruiz added a note to the report. Payments consistent with ongoing concealment agreement.

Subject likely aware of abduction status. Meanwhile, Michael’s life began to crumble under the weight of truth. He had been working at his company for three years when the news broke. But after the headlines, co-workers avoided him. Some looked at him with pity, others with suspicion. Reporters camped outside his apartment. His employer quietly placed him on leave.

Every part of his identity, name, degree, birth certificate, was suddenly in question. When investigators asked if he wanted to meet the Halleys, he didn’t answer right away. “I don’t know who I am,” he said finally. “What if I’m not who they remember?” In Florida, the reunion was being prepared carefully.

Mark and Carol How had agreed to cooperate with law enforcement’s psychological team before any meeting. They were warned that the man they would meet was not the child they had lost. His memories were gone. His life had followed a different path. You have to meet him as he is, a counselor told them, not as he was. While that process unfolded, investigators in Jacksonville searched old properties linked to the suspect, Frank Dalton.

One in particular drew attention, a rented cabin near the Suani River. The lease was dated 1987, 4 months after George’s disappearance. When detectives visited the site, now abandoned and swallowed by weeds, they found remnants of children’s clothing in the crawl space beneath the floorboards. One piece stood out. A small red sneaker preserved by the damp soil.

The rubber sole had initials scratched faintly into it. GH. The shoe was tested at the state lab. DNA extracted from the inner lining matched both the Halley samples and the profile from the Ohio donor. The evidence was irrefutable. George had been there. Linda Avery’s demeanor changed after that.

In a final interview, she admitted that Frank had hinted the child wasn’t supposed to be found. When she asked what he meant, he told her not to ask questions, that he was protecting the boy from something. She claimed she believed him. “He seemed kind,” she said softly. He said the boy was better off. The investigators didn’t believe the kindness.

What they saw was a quiet network of lies that had stretched nearly two decades. One person to take, another to hide, and an innocent child caught in the middle. But there was still no sign of Frank Dalton himself. Fingerprints from the cabin returned no match in any federal database. His name appeared nowhere after 1996. Some believed he had died. Others suspected he had simply vanished into another name, another state, another story.

When the authorities finally arranged the meeting between Michael and the Halls, it took place in a closed conference room at the sheriff’s office in Lake County. No cameras, no reporters, just three people, and a silence that seemed to fill every corner. Carol entered first, her hands trembling. Mark followed, stiff and pale. Across the table sat the man who by every test and record was their son.

He stood slowly, uncertain, as if afraid that moving too quickly might shatter something invisible between them. For a long time, no one spoke. Then Carol reached out and touched his arm. “You have his eyes,” she whispered. Michael swallowed hard, his voice low. “I don’t remember,” he said. She nodded. It’s all right. You’re here now.

The reunion didn’t end in tears or grand gestures. It ended in quiet. The kind that only comes when truth arrives too late to feel like a victory. The police called it a resolution. The Hal’s called it a beginning. Michael wasn’t sure what to call it at all. That night, Sheriff Ruiz reopened the evidence log one last time. He wrote a single line before closing the folder.

The boy from the lake was never lost. He was just living under another name. But in the empty spaces of the report, unanswered questions still waited. Who had Frank Dalton really been? Why had he taken George? And why had he let him live? Those answers, Ruiz knew, would not come easily. Because sometimes the people who vanish aren’t the only ones who disappear.

By late 2005, the Halley case had shifted from miracle to mystery once more. The country had moved on to the next headline. But in Lake County, investigators were still piecing together the final fragments of what had happened to George Hley, now Michael Avery, after his disappearance. The arrest of Linda Avery had led to a flood of records, interviews, and speculation.

Yet one name still anchored every report like a dark weight. Frank Dalton. He had vanished without a trace. No confirmed sightings, no fingerprints in the system, no tax record or driver’s license renewal. For months, detectives worked under the assumption that Dalton was dead. Then in October, the FBI received an unexpected tip from Texas.

A retired motel owner in Bowmont claimed that years earlier, a man named Frank D had stayed there long term with a small boy, paying in cash and giving no last name. The dates matched 1988 to 1989. Investigators suspected Dalton had been using a network of assumed names. A background check revealed that a Francis Day, matching his approximate age, had applied for a mechanic’s license in New Mexico in 1991.

When authorities located the facility, the record listed him as deceased, 1998, cause of death, traffic accident. But the body had been cremated before any identification could be verified. There were no fingerprints, no DNA sample preserved. Whether that man had truly been Dalton, no one could say.

The case against Linda Avery, however, moved forward. She was charged with obstruction of justice, falsification of records, and unlawful adoption. Her defense argued she had acted out of compassion, not malice, that she had given a home to a boy who had already lost his family.

But the prosecution presented the evidence of the hidden payments, the falsified documents, and the shoe from the cabin by the Suani River. She may not have taken him, the district attorney said, but she kept him hidden long enough to bury the truth. The trial was not televised. Carol and Mark Howie sat through every session, quiet, composed, their hands clasped in the gallery.

Michael George attended only once at the request of the court to confirm his identity. When asked by the judge if he recognized the woman who had raised him, he said softly, “She’s the only mother I remember.” The courtroom fell silent. In the months that followed, the case became the subject of national debate.

Was Linda a criminal or just another victim? How had a man like Frank Dalton been able to take a child and disappear so completely in the modern age? Federal agencies reviewed child protection protocols from the 1980s, citing the case as evidence of how easily an identity could be rewritten before digital systems connected the states. But for Sheriff Ruiz, the unsolved part of the story haunted him most.

He spent nights in his office rereading the file, trying to fill in the missing 5 years between 1987 and 1992. Somewhere in that gap, a six-year-old boy had been moved from one state to another, kept hidden, renamed, and given a new life. Why? There was no ransom, no revenge, no connection between Dalton and the Hals. It wasn’t a typical kidnapping. For Michael, adjusting to the truth was harder than anyone expected.

The Halls invited him to stay in Palm Bay for a while to relearn his roots, to see the place where his life had begun. He agreed, though the first days were strange and heavy. The lake was smaller than he imagined, the trees shorter, the red earth faded. He stood by the waterline one afternoon alone holding the small plastic boat retrieved from the evidence box.

It was still intact after 18 years, the rope still coiled. He set it gently on the surface of the water and watched it drift for a moment before it turned and floated back to shore. Time softened the story, but it never erased it. For the world, the case of George Halley became a headline long forgotten.

For those who lived it, it was a quiet echo that never left the room. Michael, now in his 40s, built a steady life under his real name. He moved to Tampa, worked as a systems technician, kept few friends, and stayed away from cameras. Sometimes he visited his mother, Carol, on weekends. They sat by the water, not speaking much.

Silence had become their way of remembering. Mark passed away in 2012. His obituary mentioned one line about the son who came home after 18 years. Carol kept the newspaper folded beside the piano. She still played sometimes softly, as if the sound could fill the spaces that time had taken. When asked once by a journalist why he never sought therapy for what happened, Michael said, “Because I don’t remember being lost, I only remember being found.

” It wasn’t denial. It was survival. Linda Avery lived quietly after her release. She never saw Michael again. Before she died in 2018, she left a sealed letter addressed to him. It contained only one sentence. I never meant to steal your life, only to give you one.

The red toy boat was placed in a glass case at the small museum near Silverpine Lake. One artifact from a story that still makes park rangers lower their voices when they tell it. Each spring, Carol visits the plaque under the cypress tree. She wipes the dust, replaces the faded flowers, and stands for a while before whispering the same words. You came back. That’s enough.

And when she leaves, the lake ripples gently as if answering her. The case of George Halley closed on paper long ago, but its truth remains in quieter places. The kind that don’t make headlines, the kind that remind us not every disappearance ends in loss. Some end in rediscovery, fragile but real, like a reflection returning to still water after a long storm. Because sometimes what’s gone doesn’t stay gone.

It just waits for someone to look again. Thank you for watching and for following this story to its quiet end. Where are you watching from? If case move you, stories of loss, rediscovery, and the strange ways truth finds its way back, then please subscribe to the channel, leave a comment, and share this video.