In the depths of a Belgian forest 40 years after World War II ended, a metal detector’s persistent beeping would unlock one of the war’s most haunting mysteries. What searchers found beneath decades of moss and earth would reveal a story of courage, sacrifice, and unexpected humanity that history had forgotten.

Before we begin, if you feel a deep respect for the courage and sacrifice of World War II warriors, please share your thoughts or stories in the comments below to honor their memory. Now, let’s step into that fateful October morning in 1984, when one man’s discovery would bring their story back to light. The morning mist clung to the Arden Forest like the ghosts of winter past.

Henri Dubois adjusted his headphones and swept his metal detector across the forest floor with the methodical patience of a man who had spent countless weekends searching these Belgian woods for fragments of a war that had ended before his birth.

The devices familiar hum was interrupted by an insistent beeping that made his pulse quicken. This wasn’t the typical ping of a spent bullet casing or discarded helmet fragment. This signal was strong, deep, and somehow different. He knelt among the ferns and fallen leaves, brushing away decades of forest debris with trembling hands. The October air carried the earthy scent of decomposing leaves and the faint metallic tang that old battlefields never quite lose.

As his fingers probed the soft earth, they encountered something solid, unyielding metal. Lots of it. Henry’s mind raced as he began to comprehend the magnitude of his discovery. Somewhere beneath his feet lay a piece of history that had been swallowed by time and nature’s patient reclamation. He had no way of knowing that he was about to uncover the final resting place of Captain Marcus Steel Sullivan and his crew, men who had vanished without a trace during one of World War II’s most desperate battles. The year was 1984 and the world had moved on from the

horrors of the 1940s. The Cold War dominated headlines. Technology was reshaping daily life and the veterans of the Second World War were aging into grandfathers who shared their stories with increasingly distant grandchildren. But here, in this quiet corner of Belgium, where tourists rarely ventured, the past was about to reach up from its grave and demand to be remembered.

As Henry carefully marked the location with bright orange surveyors tape, he couldn’t have imagined the story that would unfold from this moment. A story that began 40 years earlier in the brutal winter of 1944 when American tank crews faced impossible odds against a desperate German offensive that would become known as the Battle of the Bulge.

A story of four young men whose courage and humanity would shine through even in their darkest hour. The forest around Enri stood silent as if holding its breath. Somewhere in the distance, a church bell told the hour. Its bronze voice carrying across the valleys where American and German soldiers had once fought and died.

The metal detector continued signals, mapping the outline of something large buried beneath the earth. Something that had been waiting for decades to tell its story. But to understand the significance of Enri’s discovery, we must travel back to that bitter winter of 1944, when Europe trembled under the weight of the war’s final desperate gambit.

We must return to a time when young men climbed into steel coffins every morning, knowing that each mission might be their last, and when the line between heroism and survival blurred in the fog of battle. The Western Front in autumn 1944 was a landscape of contradictions. Allied forces flushed with the success of D-Day and the liberation of France had pushed German armies back across hundreds of miles of occupied territory.

In the headquarters of Supreme Allied Commander Dwight Eisenhower, maps showed German forces in retreat. Their defensive lines stretched thin across a front that extended from the North Sea to the Swiss border. Yet beneath the optimism of Allied commanders, lay a growing unease.

Operation Market Garden, Montgomery’s ambitious attempt to end the war by Christmas 1944, had failed spectacularly at Arnham. The German war machine, though battered and bloodied, continued to resist with the ferocity of a cornered animal. Vermach divisions that should have been shattered were somehow reforming behind the rine, and intelligence reports spoke of new weapons, new tactics, and a enemy leadership growing increasingly desperate.

The Arden region of Belgium and Luxembourg had become what American soldiers called the ghost front. It was considered a quiet sector, a place where green replacement troops could gain experience and battleweary veterans could rest between major operations. The forests and hills that had seen fierce fighting in World War I seemed peaceful in the autumn of 1944, their beauty masking the network of bunkers, minefields, and observation posts that both sides had constructed.

Allied intelligence had dismissed the Arden as unsuitable for major offensive operations. The terrain was too rough, the roads too narrow, the weather too unpredictable for the kind of mass armored assault that characterized modern warfare. It was this fundamental miscalculation that would set the stage for Hitler’s last great gamble and the disappearance of Captain Marcus Sullivan and his crew.

In the villages scattered throughout the Arden, Belgian civilians went about their daily lives with the cautious optimism of people who had endured four years of occupation. They had welcomed American liberators with genuine joy. But they also remembered the false hope of 1940 when French and British forces had promised to defend their homeland only to collapse within weeks.

The older villagers, those who remembered the previous war, watched the skies nervously and kept their sellers stocked with provisions. The American first army held the northern portion of the Arden sector with the eighth corps responsible for a front that stretched over 80 mi of forest and farmland.

It was a dangerously thin deployment for such a vast area, but Allied commanders were confident that the difficult terrain would channel any German attack into predictable avenues where it could be contained and destroyed. Among the units holding this deceptively quiet front was the 712th Tank Battalion, a formation that had earned its reputation in blood across the battlefields of North Africa, Sicily, and Normandy.

By December 1944, the battalion bore little resemblance to the eager unit that had shipped out from Fort Knox two years earlier. Combat had winnowed their ranks and hardened the survivors into a brotherhood forged in cordite and shared terror. Tank warfare in 1944 had evolved into a deadly chess match between increasingly sophisticated weapons and tactics.

The Sherman tank that formed the backbone of American armored forces was reliable, mechanically sound, and could be produced in vast quantities, but it was also under gunned and underarmored compared to its German counterparts. American tank crews knew that in a straight fight with a Panther or Tiger tank, their chances of survival were slim.

The Sherman’s 75 mm gun could penetrate German armor only at close range, while German anti-tank weapons could destroy a Sherman from distances that made retaliation impossible. Tank crews developed their own grim terminology for the phenomenon brewing up when a Sherman’s ammunition exploded, turning the tank into a crematorium for its crew.

The average life expectancy of a Sherman tank in combat was measured in days, not weeks. Yet, American tank crews had advantages that couldn’t be measured in millimeters of armor or muzzle velocity. They had superior communications, better training in combined arms tactics, and most importantly, they had leaders who understood the tanks were not invulnerable weapons of war, but complex machines that required constant maintenance, careful positioning, and intimate coordination with infantry and artillery. Inside a Sherman tank during combat operations, five men shared a

space smaller than most modern bathrooms. The tank commander stood in the turret, his head and shoulders above the armored roof, scanning for threats while coordinating with other units over the radio. The gunner and loader worked in cramped efficiency, loading and firing the main gun, while the driver and assistant driver in the hull below navigated treacherous terrain and operated the tank’s machine guns.

The psychological strain of tank warfare was enormous. Crews were sealed inside their machines for hours at a time, breathing recycled air thick with cordite fumes and engine exhaust. The noise was overwhelming. The roar of the engine, the clatter of tracks on stone, the metallic ping of small arms fire bouncing off armor, and the earthshaking crash of incoming artillery.

Many tank crews suffered from what would later be recognized as post-traumatic stress, though in 1944 it was simply called battle fatigue and treated with rest and rotation when possible. Communication between tanks relied on radio systems that were prone to interference and mechanical failure. A tank crew cut off from radio contact was essentially blind and deaf, forced to make split-second decisions based on what they could see through narrow vision ports and periscopes.

It was this isolation that made tank commanders like Marcus Sullivan so valuable to their units and so vulnerable to the chaos of battle. The bond between tank crew members was unlike anything found in other military units. They lived together, fought together, and knew that their survival depended absolutely on each other’s competence and courage.

A good tank crew functioned like a single organism, anticipating each other’s actions and communicating through gestures and abbreviated phrases that outsiders couldn’t understand. Captain Marcus Steele Sullivan embodied everything the army looked for in a tank commander. Born in Detroit in 1919, he had grown up in a neighborhood where the sounds of industry provided a constant soundtrack to daily life.

His father worked on the assembly line at Ford, installing engines in the Model A cars that were revolutionizing American transportation. His mother took in sewing to help make ends meet during the lean years of the depression. Marcus showed an early aptitude for mechanical things. He could strip down and rebuild a car engine before his 16th birthday.

and his teachers at Cass Technical High School recognized his potential by recommending him for a scholarship to Wayne State University. He was studying mechanical engineering when the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor changed everything. Like millions of young American men, Marcus felt the call to serve his country in its hour of need.

He enlisted in the army in February 1942, leaving behind his studies, his job at a local garage, and Ellen Marie Thompson, the girl he had planned to marry after graduation. Ellen gave him a small gold locket with her photograph inside, making him promise to come home safely so they could start the life they had dreamed about.

The army recognized Marcus’ potential immediately. His mechanical knowledge, leadership abilities, and calm demeanor under pressure marked him for rapid promotion through the ranks. At Fort Knox, Kentucky, he excelled in all phases of armored warfare training, from gunnery and tactics to maintenance and leadership.

His instructors noted his ability to remain focused under the intense pressure of simulated combat exercises and his talent for keeping his crew working together as a cohesive unit. Marcus earned the nickname steel, not for any display of ruthless efficiency, but for his unshakable calm in the face of danger.

While other tank commanders might panic when faced with mechanical problems or enemy contact, Marcus would methodically work through solutions with the same patient determination he had shown rebuilding engines in his father’s garage. His crew came to trust him absolutely, knowing that he would never ask them to take risks he wouldn’t take himself. By the time Marcus reached combat in North Africa, he was already a seasoned leader despite his youth.

The crucible of tank warfare against Raml’s Africa Corps taught him lessons that no training exercise could provide. He learned to read terrain like a book, identifying hullown positions where his Sherman could engage German armor while minimizing his own exposure.

He learned to coordinate with infantry and artillery using combined arms tactics to overcome the technical superiority of German equipment. More importantly, Marcus learned to manage the psychological toll that combat took on his crew. He developed rituals and routines that helped his men cope with the stress of battle. Morning equipment checks that were as much about morale as maintenance.

shared meals where crew members could talk about anything except the war and letters from home that he encouraged them to read aloud to each other. Through Sicily and the Italian campaign, Marcus’ reputation grew. He was the tank commander who could be counted on to complete impossible missions and bring his crew home alive. His Sherman, painted with the nickname Detroit Steel in honor of his hometown, became a familiar sight to infantry units who knew they could rely on his support when the shooting started.

The Normandy invasion tested Marcus and his crew like nothing they had experienced before. The hedro country of northern France favored defenders who could turn every field into a killing ground. German anti-tank teams armed with panzer fasts could destroy a Sherman from concealment before the crew even knew they were under attack.

Marcus learned to read the subtle signs that indicated enemy presence. Disturbed earth that might conceal mines, shadows that didn’t quite match the surrounding terrain, birds that suddenly stopped singing. Through the breakout from Normandy and the race across France, Marcus’ crew became legendary within the 712th Tank Battalion.

Sergeant Tommy Wrench Rodriguez, his gunner, could put a 75 mm shell through a window at 800 yardds. Corporal Billy Lucky O’Brien had an almost supernatural ability to navigate treacherous terrain and avoid obstacles that would bog down other tanks. Private Jake Kid Morrison could load the main gun faster than anyone in the battalion, maintaining a rate of fire that often meant the difference between victory and death.

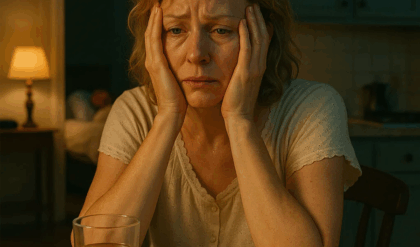

But combat was taking its toll on all of them. Marcus had seen too many friends die, watched too many Shermans brew up with their crews trapped inside. In his letters to Ellen, he tried to maintain an optimistic tone, but she could read between the lines. His handwriting was more hurried now, his sentences shorter and more abrupt. He wrote about mechanical problems and supply shortages, but never about the nightmares that kept him awake, or the faces of dead comrades that haunted his dreams.

By November 1944, as the 712th Tank Battalion took up positions in the Arden sector, Marcus Sullivan was a different man than the eager young engineer who had enlisted nearly three years earlier. The war had aged him beyond his 25 years, carving lines around his eyes, and teaching him hard lessons about leadership, sacrifice, and the terrible mathematics of survival.

He had learned that courage wasn’t the absence of fear, but the ability to function despite it. The 712th Tank Battalion had been formed at Camp Poke, Louisiana in March 1942, part of the massive expansion of American armored forces that followed Pearl Harbor. The original cadre consisted of regular army officers and sergeants supplemented by National Guard units from across the South and Midwest.

By the time they shipped out for overseas duty, they had trained together for over a year, forging the bonds of unit cohesion that would prove crucial in combat. The battalion’s journey to the European theater of operations had taken them first to England, where they spent months in additional training exercises on the moors of Yorkshire and Devon.

British officers who had learned hard lessons in the North African desert shared their knowledge about German tactics and equipment. American crews practiced coordinating with Royal Air Force fighter bombers, learning the complex procedures that would allow them to call for air support when ground communications failed.

The 712th landed at Omaha Beach 3 weeks after D-Day, driving their Shermans off landing ship tanks into the chaos of the Normandy buildup. They had their first taste of combat during the grinding battle for the hedge where every field became a potential killing ground and German defenders turned centuries old Norman farmland into a fortress.

Colonel James Harrison commanded the battalion with the steady professionalism of a career officer who had learned his trade in the peaceime army of the 1930s. A graduate of West Point’s class of 1928, he had served in various stateside assignments before the war, learning logistics and administration during the lean years when the entire US Army numbered fewer than 200,000 men.

The war had given him opportunities for promotion and command that would have taken decades in peace time. Harrison understood that his battalion’s effectiveness depended not just on the technical proficiency of his tank crews, but on their morale and unit cohesion. He made it a point to know every officer and senior non-commissioned officer personally.

Learning about their families, their backgrounds, and their individual strengths and weaknesses. When casualties mounted during the brutal fighting in France, he insisted on writing personal letters to the families of every man killed or wounded under his command. The battalion had been reinforced several times since Normandy, but these replacement crews lacked the experience and unit cohesion of the original members.

Fresh-faced young men straight from statesside training bases found themselves assigned to tanks alongside veterans who had survived months of combat. The integration process was difficult and sometimes deadly as green crews made mistakes that more experienced tankers had learned to avoid. By December 1944, the 712th Tank Battalion was a mixture of battleh hardened veterans and nervous replacements.

They had been assigned to what their intelligence briefings described as a quiet sector, a place where new crews could gain experience without facing the intensity of major offensive operations. The Arden seemed peaceful after the grinding battles they had fought across France, and many of the men began to hope that they might survive the war after all.

The battalion’s maintenance section worked around the clock to keep their Shermans operational. Tank warfare was as much about mechanical reliability as combat effectiveness, and experienced maintenance crews could mean the difference between a successful mission and a catastrophic breakdown in enemy territory. Sergeant Major Ali, the battalion’s senior mechanic, had served in the peacetime army since 1924 and could diagnose engine problems by the sound of a tank’s exhaust.

Intelligence briefings during late November 1944 had begun to mention increased German activity behind enemy lines. Luftwafa reconnaissance flights were being detected more frequently and radio intercepts suggested that German forces were moving fresh units into the Arden sector.

But these warnings were discounted by higher headquarters which remained convinced that the difficult terrain made any major German offensive impossible. The men of the 712th continued their routine of patrols, maintenance, and training exercises, unaware that across the German lines, Hitler was preparing to stake everything on one last desperate gamble. Three entire German armies were moving into position under cover of darkness, their commanders under strict orders to maintain radio silence and avoid any activity that might alert Allied intelligence to their presence. On the

evening of November 30th, 1944, Colonel Harrison held his regular briefing for company commanders and senior officers. The meeting took place in a converted Belgian farmhouse that served as battalion headquarters. Its thick stone walls offering protection from artillery fire, while its large kitchen provided space for maps and communications equipment.

Hurricane lamps cast flickering shadows on the faces of officers who had aged years in the months since Normandy. Marcus Sullivan sat with the other company commanders around a rough wooden table that had probably served Belgian farm families for generations. The contrast between the peaceful domestic setting and the tools of war spread across its surface seemed to symbolize everything the war had done to ordinary life in occupied Europe.

Maps marked with unit positions and enemy locations covered family photographs and children’s drawings that the farmhouse’s previous occupants had left behind in their hurried evacuation. Colonel Harrison’s briefing was routine, covering supply issues, personnel replacements, and patrol schedules for the coming week. Intelligence reported light enemy activity along their sector of the front with occasional probing attacks that seemed designed more to gather information than to achieve territorial gains.

German artillery fire had decreased over the past week, leading some officers to speculate that the enemy was withdrawing forces to defend against expected Allied offensives elsewhere along the front. Gentlemen, Colonel Harrison said, his voice carrying the flat vowels of his Nebraska upbringing, I want to emphasize that we cannot allow this quiet period to make us complacent. The Germans are still out there, and they’re still dangerous.

Every patrol, every observation post, every radio check needs to be executed with the same attention to detail we would use if we expected major combat operations. The colonel’s words proved more prophetic than anyone in that room could have imagined.

As the American officers planned their routine operations, German forces were completing final preparations for Operation Watch on the Rine. Hitler’s plan to split Allied armies and recapture the vital port of Antworp. Over 250,000 German troops, supported by nearly a thousand tanks and assault guns, were poised to attack along a front that the Allies considered too quiet to require heavy defensive preparations.

Marcus Sullivan raised his hand to ask about ammunition resupply, a chronic concern for tank commanders whose main guns consumed rounds at an alarming rate during combat operations. The 75 mm shells that his Sherman carried were effective against German armor only at close range, requiring him to expose his tank to enemy fire in order to achieve killing hits.

More rounds meant more tactical flexibility, the ability to engage targets at longer range without worrying about conserving ammunition for more dangerous encounters. Sir, Marcus said, “My crew is down to 60 rounds of main gun ammunition. We’ve been using quite a bit during training exercises with the new replacement crews.

When can we expect the next supply convoy?” Colonel Harrison consulted his notes before responding. “The next scheduled resupply is December 3rd, Captain Sullivan. Can your crew make do until then?” “Yes, sir. We’ll manage.” As the briefing concluded and officers prepared to return to their units, Marcus lingered to speak privately with Colonel Harrison.

The two men had developed a professional relationship based on mutual respect and shared combat experience. Harrison valued Marcus’ tactical judgment and calm leadership under pressure. While Marcus appreciated his commander’s willingness to listen to suggestions from subordinate officers. Colonel Marcus said quietly. I’ve been talking to some of the local civilians. They’re nervous about something.

More nervous than usual. I mean, an old farmer near our position told me his dogs have been restless for the past week, barking at sounds he can’t identify. And Sergeant Rodriguez mentioned that German artillery fire seems to be coming from different positions than last week. Harrison nodded thoughtfully. Combat veterans learned to trust their instincts about such things, understanding that small details often provided early warning of larger developments.

What’s your assessment, Captain? I think something’s coming, sir. I can’t put my finger on it, but everything feels different. The quiet is too complete, if that makes sense. It’s like the Germans are holding their breath. I’ll pass your concerns up to division level, Harrison promised. In the meantime, make sure your crew is ready for anything.

And Captain, he paused at the farmhouse door. Trust your instincts. They’ve kept you alive this long. Marcus returned to his tank in the pre-dawn darkness of December 1st, 1944. The Detroit Steel sat in a carefully prepared position that offered both concealment and fields of fire toward the German lines.

Sergeant Rodriguez was already awake performing the morning maintenance checks that had become second nature after months of combat. The ritual of inspecting tracks, engine oil, transmission fluid, and ammunition provided a sense of normaly that helped combat crews cope with the constant stress of their situation. Morning, Captain Rodriguez said, his Mexican accent softened by years of military service.

She’s running sweet as a nut. New oil filter made all the difference. Corporal O’Brien emerged from beneath the tank where he had been checking the final drive assemblies. His uniform was black with grease and oil, the inevitable result of maintaining complex machinery under field conditions. Drivers ready, sir. Fuel, oil, everything’s topped off.

Private Morrison, the youngest member of the crew at 19, was cleaning the main gun with the obsessive attention to detail that marked him as a professional soldier despite his youth. The 75 mm cannon could mean the difference between life and death in combat, and Morrison treated it with the reverence that others might reserve for religious artifacts.

As the crew completed their morning preparations, Marcus climbed into the commander’s position and began his radio checks with battalion headquarters and neighboring units. The familiar routine of call signs and response codes provided reassurance that they were part of a larger organization, not isolated in hostile territory. Each successful radio contact was a small victory against the isolation and fear that constantly threatened to overwhelm tank crews in combat.

Steel 6, this is blue base, came the voice of the battalion communications officer. Radio check over. Blue base, steel six. Layma charlie over. Roger. Steel six. Maintain present position and observe. Report any unusual activity. How copy. Solid copy blue base steel six out. The radio crackled with similar exchanges as other tank commanders checked in with headquarters.

The morning was crisp and clear with visibility good despite patches of ground fog in the low areas. It seemed like an ideal day for routine patrolling and observation. The kind of quiet morning that allowed combat veterans to catch their breath and remember what peace felt like. Marcus opened Ellen’s latest letter, reading again words he had already memorized.

She wrote about her job at the defense plant back in Detroit, manufacturing engine parts for B24 bombers. Her letters were determinately cheerful, full of news about mutual friends and plans for their future together. But Marcus could sense her growing worry in the spaces between words, the careful way she avoided asking directly about his combat experiences.

When you come home, she had written, well take that trip to Machinak Island that we always talked about. Just you and me and all the time in the world to figure out what comes next. I love you more than words can say, and I’m counting the days until this terrible war is over, and you’re safe in my arms again.” Marcus folded the letterfully and returned it to his breast pocket next to the small gold locket she had given him before he shipped overseas.

He had read those words hundreds of times, drawing strength from her love and the promise of a future beyond the war. Ellen represented everything he was fighting for, home, family, a chance to build something lasting in a world that often seemed bent on destroying everything beautiful and good. At 800 hours, Marcus received orders to advance to an observation post 3 km closer to the German lines.

Intelligence reports suggested increased enemy activity in the area and battalion wanted firsthand reconnaissance from experienced crews. It was exactly the kind of mission that Marcus and his crew had executed dozens of times before, move forward undercover, establish observation positions, and report enemy movements back to headquarters. Okay, gentlemen, Marcus announced to his crew.

We’re going hunting. Load up with extra ammunition and rations for 24 hours. Rodriguez, make sure we have plenty of radio batteries. O’Brien, plot our route and identify alternate positions in case we need to displace quickly. Morrison, check our smoke grenades and emergency signals.

The crew moved with the practice deficiency of men who had performed these preparations countless times before. Each man knew his responsibilities and the importance of attention to detail. In tank warfare, small oversightes could lead to catastrophic failures, and survival depended on getting everything right the first time.

As Detroit steel rumbled out of its prepared position, Marcus stood in the commander’s hatch, scanning the terrain ahead. The Arden landscape was beautiful in the morning light with frost glittering on the pine needles and deer trails visible in patches of snow. It was hard to believe that this peaceful forest concealed deadly enemies and would soon become a battlefield where thousands of men would fight and die.

The radio crackled with routine traffic as other units reported their positions and status. Everything seemed normal, part of the daily routine that had characterized the past month in this supposedly quiet sector. Marcus felt the familiar mixture of alertness and boredom that marked routine combat operations, where long periods of tedium could be shattered instantly by moments of terrifying action.

At 0847 hours, as Detroit Steel approached its assigned observation position, Marcus spotted movement in the treeine ahead. At first, it appeared to be nothing more than shadows shifting in the morning breeze. But his combat experience had taught him to trust his instincts, and something about the movement pattern didn’t look natural.

Blue base, this is Steel 6, he radioed back to battalion headquarters. Movement observed in grid square 245678. Investigating. Over. Roger. Steel 6. Investigate and report. Be advised, other units report similar contacts this morning. Over. Those were the last words that battalion headquarters would hear from Captain Marcus Steel Sullivan and the crew of Detroit Steel.

At precisely 0847 hours, as German forces launched Operation Watch on the Rine across a 60-mile front, one American tank crew vanished into history. What happened to them in the hours and days that followed would remain one of World War II’s most haunting mysteries until Henri Dubois heard his metal detectors insistent beeping.

On that October morning in 1984, the Battle of the Bulge exploded across the Arden with a fury that stunned Allied commanders and shattered the illusion of German weakness. Three entire German armies totaling over 250,000 men smashed into American defensive positions that had been designed to hold a quiet sector, not repel a major offensive.

In the space of a few hours, the careful defensive plans that Allied commanders had developed were rendered obsolete by the sheer weight of the German attack. The German offensive achieved complete tactical surprise. Hitler had managed to conceal the movement and concentration of massive forces despite Allied air superiority and intelligence networks that had proven remarkably effective throughout the war.

Radio silence, movement only at night, and elaborate deception measures had allowed German commanders to position three armies within striking distance of American lines without detection. The initial German assault fell most heavily on the 106th Infantry Division, a newly arrived unit that had been sent to the Arden to gain combat experience in what was considered a quiet sector.

Within hours of the attacks beginning, two entire regiments of the 106th were surrounded and cut off, creating gaps in American lines that German armored spearheads exploited ruthlessly. For the men of the 712th Tank Battalion, the German offensive transformed routine morning operations into a desperate struggle for survival.

Radio networks that had functioned smoothly the day before were jammed with panicked reports of breakthrough, encirclement, and units under heavy attack. The careful coordination between friendly forces broke down as German infiltration teams cut telephone lines and radio jamming disrupted communications. Colonel Harrison’s headquarters received fragmentaryary reports that painted a picture of disaster unfolding across his battalion sector.

Tank crews that had been conducting routine patrols found themselves engaged in running battles with German forces that seemed to appear from nowhere. The quiet sector that intelligence had assured them was lightly held suddenly swarmed with enemy troops, tanks, and anti-tank teams. All steel units, this is Blue Base. Colonel Harrison’s voice crackled over the radio network. Report your status immediately.

We are under heavy attack across the entire front. One by one, tank commanders reported their situations. Steel 2 was engaged with German infantry near the village of Crinkled. Steel 4 had been hit by anti-tank fire and was withdrawing under smoke cover. Steel 7 was out of radio contact, last seen moving toward enemy positions to support surrounded infantry, but there was no response from Steel 6, Captain Marcus Sullivan’s tank.

Despite repeated radio calls, Detroit Steel remained silent. In the chaos of the German offensive, one missing tank seemed like a minor loss compared to the larger disaster unfolding across the Arden. But for the men who had served with Marcus Sullivan, his disappearance left a void that would never be completely filled.

The German offensive that became known as the Battle of the Bulge was Hitler’s last desperate gamble to change the course of World War II. Conceived in the summer of 1944 as German forces reeled back from the collapse of Army Group Center on the Eastern Front and the breakout from Normandy in the west.

The operation was intended to split Allied armies and recapture the vital port of Antworp. Hitler’s plan required German forces to advance over a 100 miles through difficult terrain, cross multiple river barriers, and capture objectives defended by increasingly alert Allied forces. The operation’s success depended on achieving surprise, maintaining the momentum of the initial assault and capturing Allied fuel dumps to keep German armor moving toward its objectives.

From the beginning, the offensive faced problems that its planners had failed to anticipate. Fuel shortages plagued German units, forcing tank crews to abandoned vehicles that ran out of gas within sight of their objectives. Allied air power, grounded by bad weather during the first few days of the offensive, returned to devastate German supply columns and troop concentrations as soon as visibility improved.

Most critically, American resistance proved far more determined than German intelligence had predicted. Units that should have collapsed under the weight of surprise attack instead fought desperate delaying actions that slowed German advances and allowed Allied reserves to deploy. The battle of Baston became symbolic of American determination, but similar acts of heroism occurred at crossroads and villages across the Arden.

The human cost of the Battle of the Bulge was enormous for both sides. American casualties exceeded 89,000 killed, wounded, and missing, making it one of the costliest battles in American military history. German losses were even higher, particularly in experienced officers and non-commissioned officers whose deaths gutted the Vermach’s remaining combat effectiveness.

For the families of men who disappeared during the battle, the human cost was measured not just in death, but in uncertainty. Thousands of American soldiers were listed as missing in action, their fates unknown to loved ones who spent years hoping for news that might never come. The chaos of the German offensive and the subsequent Allied counterattack left many battlefield sites unexplored, their secrets buried beneath snow, rubble, and the patient accumulation of seasons.

Among those secrets was the final resting place of Captain Marcus Sullivan and his crew, men who had vanished into the fog of war during the opening hours of Hitler’s last offensive. Their disappearance represented one small tragedy in a battle that consumed entire divisions and reshaped the strategic balance of the war. But for those who knew them, their absence left questions that would persist for 40 years.

The search for Detroit steel began within hours of Marcus Sullivan’s final radio transmission. Despite the chaos that engulfed American forces across the Ardan front, Colonel Harrison, even as he struggled to maintain contact with his scattered tank companies, refused to abandon hope that his missing crew might still be alive.

Combat experience had taught him that tank crews could survive for days in disabled vehicles if they could avoid capture and find adequate shelter. The initial search was hampered by continuing German attacks and the fluid nature of the battle lines. Areas that were in American hands in the morning might be occupied by German forces by nightfall, making systematic searches impossible.

Battalion reconnaissance teams made several attempts to reach the position where Detroit steel had last been seen, but each effort was driven back by enemy fire or the threat of encirclement. Local Belgian civilians provided conflicting reports about American tanks in the area. Some claimed to have heard tank engines and gunfire from the direction of Marcus’ last known position.

Others reported seeing German soldiers examining a disabled American tank, though they couldn’t be certain of its identification numbers or the fate of its crew. By the end of December 1944, as American forces began their counteroffensive to eliminate the German salient, the search for Detroit steel expanded to include areas that had been behind enemy lines during the height of the battle.

Combat engineers and Graves registration teams systematically examined every knockedout tank they encountered, checking serial numbers and crew compartments for signs of Marcus Sullivan and his men. The searchers discovered dozens of destroyed American and German vehicles scattered across the Arden battlefields.

Some tanks had been completely destroyed by ammunition explosions, leaving only twisted metal and scattered debris. Others showed the characteristic damage patterns of anti-tank weapons, neat holes punched through armor plate by high velocity projectiles, or the distinctive blast damage caused by shape charge warheads. Several times during the search, teams thought they had found Detroit steel.

A Sherman tank discovered in a forest clearing near Malmidy bore a superficial resemblance to Marcus’ vehicle, but examination of its serial numbers revealed it to be from a different battalion. Another tank found buried in snow near the German border was initially identified as Detroit steel, but closer inspection showed that its crew had escaped before the vehicle was destroyed.

The most promising lead came from a Belgian farmer who claimed to have seen an American tank moving through his property on the morning of December 1st, several hours after the German offensive began. The farmer, an elderly man named Philipe Dubois, had watched from his barn as the tank approached a heavily wooded area near his property line.

He heard the sound of gunfire and explosions coming from that direction, but German patrols had prevented him from investigating further. Search teams spent two weeks examining the area Philipe Dubois had identified using metal detectors and probes to search beneath the snow and fallen leaves.

They found scattered equipment and ammunition, evidence that some kind of battle had taken place there. But there was no sign of Detroit Steel or its crew, despite the most intensive search efforts that time and resources allowed. As winter gave way to spring and Allied forces prepared for the final push into Germany, the search for Marcus Sullivan and his crew gradually lost priority.

New battles demanded attention and resources. While the administrative machinery of war processed thousands of missing personnel reports from across the European theater, Detroit Steel joined the growing list of unsolved disappearances that would remain mysteries long after the wars end. Colonel Harrison never completely abandoned hope that his missing tankers might be found alive.

Throughout the spring of 1945, he continued to interview German prisoners and examine captured documents for any reference to American tank crews taken prisoner during the Battle of the Bulge. He personally investigated reports of Americans held in prisoner of war camps, hoping to find some trace of Marcus Sullivan and his men.

The end of the war in May 1945 brought new opportunities for systematic searches of former battlefields. Units of the Graves Registration Service began the massive task of locating and identifying American remains scattered across Europe’s battlefields. Teams equipped with detailed maps and metal detectors methodically examined areas where American forces had fought, recovering bodies and personal effects for shipment home to grieving families.

The Arden search efforts continued through 1946 as teams worked to clear the forests and villages where some of the war’s fiercest fighting had taken place. The difficult terrain that had favored defenders during the battle now complicated efforts to locate missing personnel. Dense forests, steep ravines, and areas still contaminated with unexloded ordinance limited the scope of search operations.

Several times during the post-war searches, teams discovered remains that might have been from Detroit Steel’s crew. Bodies found near the village of Crinkled included one that wore captain’s insignia and appeared to be the right age and physical description to be Marcus Sullivan. But dental records and other identifying evidence proved that the remains belonged to a different officer who had died during the battle.

The most heartbreaking false identification occurred in August 1946 when Belgian workers clearing a demolished farmhouse discovered a body wearing American tanker coveralls. Personal effects found with the remains included a small gold locket containing a woman’s photograph, leading searchers to believe they had finally found Marcus Sullivan.

But the photograph was too damaged to provide positive identification. and subsequent investigation revealed that the locket had belonged to another American soldier entirely. By 1947, official search efforts for Detroit Steel had been suspended. Colonel Harrison, now serving in a peaceime assignment at Fort Knox, continued to pursue private leads and maintain contact with Belgian civilians who reported occasional discoveries of American equipment in the Arden forests.

But without new evidence or credible sightings, there was little more that could be done through official channels. The families of the missing crew members faced the agonizing uncertainty that affected thousands of American families whose loved ones had disappeared during the war.

Ellen Marie Thompson, who had waited faithfully for Marcus’ return, struggled with the lack of closure that a confirmed death might have provided. She kept his photographs on her dresser and continued to hope for news that might explain his disappearance. Tommy Rodriguez’s family in San Antonio held a memorial service in 1948, 3 years after his disappearance, but his mother refused to believe that her son was dead.

She maintained his bedroom exactly as he had left it, insisting that he would return when the army finally located him. Billy O’Brien’s parents in Boston hired a private investigator who traveled to Belgium in 1949, spending several weeks retracing the search efforts and interviewing local civilians. Jake Morrison’s sister in rural Tennessee became convinced that her brother had survived the war but lost his memory, a theory she supported by citing newspaper reports of American servicemen found in European hospitals with amnesia. She spent years writing letters to

veterans organizations and military hospitals, hoping to find some trace of the younger brother who had seemed so invincible when he left for the war. The Korean War’s outbreak in 1950 shifted public attention away from World War II’s unresolved mysteries. A new generation of American servicemen faced combat in unfamiliar terrain, and the resources that might have been devoted to continued searches in Europe were redirected to support active military operations. The case of Detroit Steel gradually faded from official memory,

joining thousands of similar mysteries in the archives of the Quartermaster General’s Office. But the story refused to die completely. Veterans of the 712th Tank Battalion maintained informal networks of communication, sharing rumors and theories about what might have happened to Marcus Sullivan and his crew.

Annual reunions provided forums for speculation about Detroit Steel’s fate, with various members proposing explanations ranging from capture and execution by SS troops to mechanical breakdown in a remote area where the crew died of exposure. Military historians who studied the Battle of the Bulge occasionally mentioned Detroit Steel’s disappearance in their accounts of the offensive, but always as a minor footnote to larger tactical and strategic analyses.

The human drama of four men vanishing into the chaos of battle could not compete with discussions of grand strategy, logistics, and the movement of armies across the European landscape. Local Belgian civilians who lived in the area where Detroit Steel had disappeared developed their own folklore about the missing American tank.

Children who played in the forests claimed to hear the sounds of tank engines on quiet nights, while adults reported strange metallic gleams in areas where no metal should exist. These stories were dismissed as imagination by most people, but they kept alive the possibility that Detroit steel might someday be found.

Philipe Dubois, the elderly farmer who had provided the most detailed account of seeing an American tank near his property, died in 1963 without ever learning what had happened to the crew he had seen heading into the forest that December morning in 1944. His son Henri inherited the farm and grew up hearing stories about the American tank that had disappeared during the Great Battle.

Henri Dubois developed an interest in World War II history that was partly personal and partly professional. As a young man in the 1960s, he began collecting military artifacts from local battlefields. Initially as a hobby, but eventually as a small business serving museums and private collectors.

His knowledge of the area’s wartime history made him a valuable guide for historians and veterans who visited Belgium to research the Battle of the Bulge. Through the 1970s, Henry expanded his collecting activities to include systematic searches of forest areas where fighting had occurred during the winter of 1944 to 45.

Metal detectors had become more sophisticated and affordable, allowing amateur historians to locate artifacts that earlier searches had missed. Henry’s systematic approach and intimate knowledge of local terrain made him particularly effective at finding items that revealed new details about the battle. Henry’s searches yielded a steady stream of artifacts, German and American helmets, weapons, personal effects, and pieces of equipment that told the story of desperate fighting in impossible conditions.

Each discovery added another piece to the complex puzzle of what had happened during those terrible weeks when the Arden had become a slaughterhouse. But the one discovery that had eluded him, despite years of searching, was any trace of the American tank his father had seen disappearing into the forest.

By the early 1980s, Henry had developed theories about where Detroit steel might be located. His father’s account, combined with his own knowledge of the terrain and battle reports he had studied in military archives, suggested several areas where a disabled tank might have sought concealment.

The forest had grown substantially in the four decades since the war, with new growth covering areas that had been clear fields in 1944. The breakthrough came on that crisp October morning in 1984 when Henry’s metal detector registered the strong deep signal that indicated something substantial buried beneath the forest floor.

Unlike the smaller signals produced by individual artifacts, this reading suggested a large metallic object several feet below the surface. HR’s excitement was tempered by caution, as previous experiences had taught him that promising signals could lead to disappointment. The initial excavation revealed pieces of track and armor plating that were unmistakably from an American Sherman tank.

Henry photographed everything carefully before disturbing the site further, understanding that the arrangement of debris might provide crucial evidence about what had happened. The metal showed battle damage, holes punched through armor plate by anti-tank weapons, scarring from high explosive impacts, and the distinctive patterns left by intense fires.

As Henri carefully expanded his excavation, the full scope of his discovery became apparent. Beneath four decades of accumulated soil, leaves, and forest growth lay the remarkably preserved remains of an American tank. The vehicle had settled into what appeared to be a natural depression, possibly a shell crater, that had filled with debris over the years and gradually been overgrown by vegetation.

The tank’s turret had been partially separated from the hull, suggesting that an internal ammunition explosion had occurred at some point during its final battle, but the crew compartment remained largely intact, sealed by the tanks armor from the elements and scavengers that had claimed so many battlefield remains over the years. Henry realized that he might be looking at one of the war’s most significant archaeological discoveries.

His first call was to the local police who arrived within an hour, accompanied by a representative from the Belgian Ministry of Defense. The official response was swift and professional, recognizing immediately that this discovery required careful handling by experts in military archaeology and forensic investigation. Within hours, the site was secured and preliminary arrangements made for a full-scale excavation. Dr.

Marie Vanderberg, Belgium’s leading expert in battlefield archaeology, arrived from Brussels the following day. She had spent her career studying the physical remains of two world wars, developing techniques for extracting maximum information from sites like this one. Her initial examination of the tank confirmed Omri’s identification of the vehicle as an American Sherman, but establishing its specific identity would require careful examination of serial numbers and other identifying features.

The excavation proceeded slowly with each layer of soil carefully removed and sifted for artifacts that might provide clues about the tank’s final battle and the fate of its crew. Dr. Vanderberg’s team included forensic specialists, military historians, and conservation experts who understood the complex challenges of preserving materials that had been buried for 40 years.

The first human remains were discovered on the third day of excavation in what had been the tank’s driver’s position. The bones were remarkably well preserved, protected by the tank’s armor from the elements and scavengers. Personal effects found with the remains included dog tags that provided positive identification.

Corporal Billy Lucky O’Brien, serial number 37854692, blood type A positive. The discovery of O’Brien’s remains confirmed Henry’s suspicion that this was indeed Detroit steel, the tank that had vanished during the opening hours of the Battle of the Bulge. But it also raised new questions about what had happened to the crew during their final hours.

The careful arrangement of personal effects and equipment suggested that the crew had survived the initial attack and had time to organize their situation before whatever final catastrophe had claimed their lives. Dr. Vanderberg’s team worked with painstaking care to document every detail of their discovery. Photographs, measurements, and detailed drawings recorded the position of every artifact before it was removed for conservation and analysis.

The process was complicated by the need to preserve evidence that might answer questions about the crew’s fate while showing respect for the human remains that represented someone’s son, brother, or fiance. The discovery of Sergeant Tommy Rodriguez’s remains in the gunner’s position yielded additional personal effects that painted a picture of men who had maintained their military discipline even in desperate circumstances.

His rosary beads were wrapped around his fingers, suggesting that he had been praying during his final moments. A small notebook found in his breast pocket contained detailed records of ammunition expenditure and mechanical problems, maintained until very near the end. Private Jake Morrison’s remains were found in the loaders position, surrounded by empty shell casings that indicated Detroit Steel had fought a prolonged engagement before being disabled.

Morrison’s youthful features were still recognizable, preserved by the conditions inside the sealed tank. Personal effects found with his body included letters from his sister and a small harmonica that he had apparently been carrying when he died. The most significant discovery came when excavators reached the commander’s position where Captain Marcus Sullivan had fought his final battle.

His remains were found in a position that suggested he had died while trying to operate the tank’s radio, perhaps attempting to call for assistance or report his situation to headquarters. The gold locket containing Ellen’s photograph was still around his neck, its contents remarkably preserved despite four decades underground. But the most shocking discovery was yet to come.

As forensic specialists examined the crew compartment more carefully, they found evidence that the tank’s occupants had survived for several days after their vehicle was initially disabled. Ration containers showed signs of having been opened and consumed systematically, while makeshift bedding suggested that the crew had organized their confined space for extended occupation.

Even more surprising was evidence that someone from outside the tank had provided assistance to the trapped crew. German ration containers and medical supplies found inside Detroit steel could only have been placed there by enemy soldiers who had discovered the disabled American tank and chosen to help its occupants rather than capture or kill them.

This discovery would challenge conventional narratives about the war and reveal the complex humanity that could exist even between enemies. The forensic investigation revealed that Detroit steel had been hit by multiple panzer rounds during its initial engagement, damaging the transmission and tracks to the point where the tank could not move.

The crew had apparently driven their disabled vehicle into the natural depression where Henri found it, seeking concealment from further attacks while they attempted to repair their equipment or call for rescue. Evidence suggested that the crew had survived in their steel shelter for at least 3 days, rationing their food and water while hoping for rescue by advancing American forces.

During this period, they had been discovered by German soldiers who, for reasons that would never be fully understood, had chosen mercy over military necessity. Rather than taking prisoners or eliminating a potential threat, these unknown German soldiers had provided food and medical supplies to help the trapped Americans survive.

The end had come suddenly, probably from a direct hit by German artillery or anti-tank fire that had penetrated the crew compartment. The men had died instantly, their bodies preserved by the sealed environment of their tank until Henry’s metal detector had announced their location to the world 40 years later. They had died together as they had lived and fought together in the steel coffin that had carried them across the battlefields of Europe. Dr.

Vanderberg’s preliminary report on the discovery sent shock waves through the military history community and captured international media attention. Here was not just another battlefield discovery, but physical evidence of the humanity that could transcend the hatred and ideology of war.

The German soldiers who had helped Detroit Steel’s crew represented thousands of individual acts of mercy that official histories rarely recorded. The notification process for the crews families proved both heartbreaking and cathartic after 40 years of uncertainty. Ellen Marie Thompson, now 64 years old and long since married to another man, wept when military officials informed her that Marcus’ remains had finally been found.

She had never stopped loving the young man who had promised to come home from the war, and learning the details of his final days provided a kind of closure she had never expected to receive. Tommy Rodriguez’s mother had died 10 years earlier, still refusing to believe that her son would never return. But his younger brother, now a grandfather himself, traveled to Belgium to see the site where Tommy had been found.

The rosary beads discovered with the remains were returned to the family, becoming treasured relics of a man who had died fighting for his country while maintaining his faith until the end. Billy O’Brien’s family had long since given up hope of learning what had happened to their relative, but they were deeply moved by evidence that he had performed his duties as driver until the very end.

His harmonica was returned to his surviving sister, who remembered teaching him to play it during childhood visits to their grandparents’ farm in rural Massachusetts. Jake Morrison’s sister had spent four decades convinced that her brother had somehow survived the war despite being listed as missing in action.

Learning that he had died with his crew mates fighting bravely in defense of his country helped her finally accept the loss she had been denying for most of her adult life. The letters from home found with his remains were returned to her, their pages yellow with age, but their words of love still clearly visible.

The discovery of Detroit steel had implications that extended far beyond providing closure for one crews families. Military historians recognized that the physical evidence from the tank provided new insights into the human dimensions of the Battle of the Bulge and the complex interactions between enemies during wartime.

The German soldiers who had helped the trapped Americans represented a side of the war that was often overlooked in conventional narratives focused on strategy and tactics. Dr. Vanderberg’s team spent months analyzing every artifact recovered from Detroit Steel, building a detailed picture of the crew’s final days and the battle that had disabled their tank. Ballistics analysis of the damage patterns revealed the sequence of hits that had knocked out the Sherman, while examination of personal effects provided insights into how the crew had coped with their desperate situation.

The conservation process for Detroit steel itself proved to be a major undertaking. 40 years underground had caused significant corrosion to the tanks steel components while organic materials like leather and rubber had deteriorated badly. Specialists worked carefully to stabilize the most important artifacts while documenting everything that could not be preserved.

The most challenging aspect of the conservation effort involved the human remains which required careful handling to preserve both their scientific value and their dignity as the mortal remains of American servicemen. Forensic anthropologists worked closely with military personnel to ensure that the crew members would receive proper burial with full military honors while preserving evidence that might answer remaining questions about their fate.

The story of Detroit Steel captured public imagination in ways that surprised even experienced military historians. Newspaper articles, television documentaries, and magazine features brought the crew’s story to millions of people who had never heard of the Battle of the Bulge or understood the human cost of armored warfare.

The discovery seemed to represent something larger than four men and their tank, the power of individual courage and sacrifice to transcend the hatred and violence of war. Military museums competed to acquire artifacts from Detroit steel, recognizing their educational value in helping visitors understand the human dimensions of warfare. The tank’s main gun, damaged beyond repair, but still recognizable, became the centerpiece of an exhibit at the National World War II Museum that told the story of American armored forces in Europe. Personal effects from the crew were displayed alongside their military records,

helping visitors connect the individual stories to the larger historical narrative. The academic community responded to the discovery with scholarly articles and conference presentations that analyze the find’s implications for understanding wartime behavior and the complex relationships between enemies during combat.

The evidence of German assistance to the trapped American crew challenged simplistic narratives about the war while highlighting the moral choices that individuals faced even in the most extreme circumstances. Perhaps most importantly, the discovery of Detroit steel provided validation for the thousands of families who had never learned the fate of relatives listed as missing in action during World War II.

The careful documentation of the crew’s final days and the respectful treatment of their remains demonstrated that even after 40 years, the sacrifice of individual servicemen could still be recognized and honored. The repatriation ceremony for the crew of Detroit Steel took place on a cold November morning in 1985, almost exactly 41 years after their disappearance.

Military officials from both the United States and Belgium participated in the ceremony, which honored not only the four American crew members, but also the unknown German soldiers who had shown mercy to their enemies during some of the war’s darkest hours. Captain Marcus Sullivan was buried in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors, his grave marked with a headstone that recorded his service from North Africa through the Battle of the Bulge.

Ellen attended the ceremony, now accompanied by children and grandchildren who had grown up hearing stories about the young man their grandmother had loved and lost. The gold locket that had preserved her photograph through four decades underground was buried with him. Sergeant Tommy Rodriguez was laid to rest in San Antonio National Cemetery.

His grave surrounded by family members who had kept his memory alive through two generations. The rosary found with his remains was blessed by the same parish priest who had prayed for his safe return in 1944. His brother spoke at the service about the importance of faith in sustaining hope through the darkest times. Corporal Billy O’Brien was buried in Massachusetts National Cemetery near the family farm where he had learned to play the harmonica as a child.

His surviving relatives gathered to honor a man they had known only through faded photographs and childhood memories. The ceremony reminded them that individual sacrifice was the foundation of their freedom and prosperity. Private Jake Morrison was interred in Tennessee State Veteran Cemetery. His grave attended by his sister and dozens of relatives who had never known him personally, but had heard his story from older family members.

His harmonica was donated to a local museum that created an exhibit about World War II veterans from the region. The discovery and repatriation of Detroit Steel’s crew had a profound impact on military policy regarding missing personnel. The case demonstrated that systematic searches of former battlefields could still yield important discoveries decades after conflicts ended, leading to expanded funding for battlefield archaeology and forensic investigation.

Modern conflicts would benefit from improved procedures for locating and identifying missing servicemen, procedures that grew partly from lessons learned in the Belgian forest. The story also influenced popular understanding of World War II and the complex relationships between combatants during wartime. The evidence that German soldiers had risked court marshal or worse to help trapped Americans provided a counternarrative to simplistic portrayals of the conflict as a struggle between absolute good and absolute evil. War, the discovery suggested, was primarily about individual human beings making moral

choices under impossible circumstances. Educational institutions incorporated the story of Detroit Steel into curricula designed to help students understand both the strategic dimensions of World War II and its human cost. The cruise story provided a concrete example of sacrifice and courage that helped young people connect with historical events that might otherwise seem remote and abstract.

Their final battle became a teaching tool for exploring themes of duty, honor, and the moral complexity of warfare. Veterans organizations embrace the story as validation of their own service and sacrifice. The careful documentation of Detroit Steel’s final battle and the respectful treatment of the crews remains demonstrated that individual contributions to military victory were still remembered and honored decades after conflicts ended.

The discovery provided comfort to aging veterans who worried that their own service might be forgotten by future generations. The physical site where Detroit steel was discovered became an informal memorial visited by military history enthusiasts, veterans, and family members of other servicemen who had disappeared during the Battle of the Bulge.

Hri Dubois, whose metal detector had started the process of discovery, served as an unofficial guardian of the site, ensuring that visitors treated it with appropriate respect and understanding its significance in the larger story of the war. International cooperation in investigating the discovery, set precedents for future battlefield archaeology projects.

Belgian, American, and German officials worked together to analyze evidence and share information, demonstrating that former enemies could collaborate in honoring the memory of those who had died during their conflict. The spirit of reconciliation that had grown from the ashes of World War II found expression in the careful investigation of Detroit Steel’s final resting place.

The German veteran who eventually came forward to admit his role in helping the trapped American crew became a symbol of the moral courage that individuals could display even during wartime. His decision to provide food and medical supplies to enemy soldiers despite the risk of severe punishment from his own commanders represented the kind of individual conscience that could transcend the hatred and propaganda of war.

His testimony given when he was in his 70s and nearing the end of his own life provided crucial details about Detroit Steel’s final days and helped complete the picture that forensic investigators had assembled from physical evidence. He described finding the disabled American tank and making the decision to help its occupants, knowing that discovery by SS troops or fanatical Nazi officers could have resulted in his execution for treason.

The veteran’s account revealed that he and several other German soldiers had returned to the tank multiple times over a 3-day period, bringing rations and medical supplies from their own limited stores. They had attempted to communicate with the trapped Americans through gestures and basic English phrases, establishing a temporary human connection that transcended the war raging around them.

His most vivid memory was of the American captain Marcus Sullivan, who had maintained military discipline and courtesy even in desperate circumstances. The German soldier remembered Sullivan thanking him in broken German and sharing photographs of his girlfriend back home. These small acts of humanity had sustained both men’s faith in human decency despite the horrors they witnessed daily.

The veteran’s decision to come forward with his story was motivated partly by guilt that he had been unable to save the American crew and partly by a desire to set the historical record straight. He had carried the memory of those three days for 40 years, wondering whether his actions had made any difference in the Americans final hours, and hoping that someday their sacrifice would be properly recognized.

His testimony was corroborated by physical evidence found in Detroit Steel and by German unit records that showed unusual requisitions of medical supplies during the period when the tank crew was trapped. Military historians use this information to piece together a detailed timeline of the crew’s final days and to understand the moral complexity of individual decisions made during wartime.

The collaboration between former enemies in investigating Detroit Steel’s story became a powerful symbol of reconciliation and the possibility of finding common humanity even in the aftermath of devastating conflict. The German veteran’s willingness to share his memories despite potential criticism from some quarters demonstrated the moral courage required to confront difficult truths about war and its impact on individual conscience.

In a Belgian forest where sunlight filters through 40 years of growth, moss and wild flowers mark the spot where four young Americans made their final stand. Their story reminds us that even in war’s darkest hours, courage and compassion can transcend the boundaries that divide us, leaving echoes that resonate across generations. The disappearance mystery of Captain Marcus Sullivan and his World War II tank crew remained one of World War II’s most haunting, unsolved mysteries for decades.

This missing person case demonstrates how wartime disappearances can leave families searching for answers across generations. The vanished without a trace soldiers of Detroit Steel represent thousands of missing in action personnel whose fates remained unknown long after the war ended.

Their story reveals how disappeared persons cases from World War II continue surfacing through modern investigation techniques and battlefield archaeology. What began as another mysterious vanishing became a powerful reminder that even in war’s darkest moments, human compassion transcends conflict. And missing persons investigations can bring closure decades