He found her bleeding in the dust, half-conscious and clutching a pendant she couldn’t explain. By dawn, 70 Navajo warriors rode to his door. But not for revenge. The girl wasn’t just anyone. She was the chief’s daughter. It was near dusk when Thomas Gable saw the riderless pony stumble into the dry creek bed below his cabin, its flank stre with blood.

At first he thought it was the horse that was wounded. But then he saw her half hanging off the saddle, one barefoot, dragging in the dust, her dark hair tangled with sweat and thorns, arms clutched around a wound that pulsed with every heartbeat. He dropped the axe, didn’t even bother to close the cabin door behind him. By the time he reached the pony, the girl had slumped forward. Navajo, no older than 15.

Her skin clammy and gray from blood loss. Her blouse was torn across the ribs, soaked through on one side, but her grip, even unconscious, was tight around the leather cord tied around her neck. A pendant hung from it, turquoise and carved bone, polished smooth with years of use.

He didn’t recognize the design, but he knew what it meant. This wasn’t just any girl. He didn’t hesitate. Thomas lifted her down, cradled her light frame in his arms, and carried her into the cabin. Inside, the fire was low and the cabin colder than it should have been for late summer.

He laid her on the cot, peeled back the blood soaked fabric, and winced at the wound. Clean slice, knife, or maybe arrowhead, but deep. Through grit teeth, he did what he could. boiled water, poured whiskey, stitched what he had to. She never woke, but her breathing steadied. That was enough.

He sat by her through the night, nodding off only once, hands still on the hilt of his revolver, just in case whoever put that wound in her came looking to finish the job. But no one came. Not until morning. Just as the sun cracked the horizon, hooves thundered across the ridgeeline. Not one or two, dozens. Thomas stepped onto the porch, eyes narrowing against the rising dust. 70 riders, Navajo, silent, proud, armed.

His hand dropped instinctively to his belt, but he didn’t draw. No one was shouting. No one reached for a weapon, and they didn’t spread out to surround him. They stopped in a clean line 50 ft from the porch. One man rode forward, older, hair bound tight, silver streaks at the temples, and eyes that didn’t blink. Thomas didn’t speak first. Neither did the rider.

For a moment it was just wind and horses and the sound of the girl’s soft breathing behind him in the cot. Then the rider dismounted, walked forward slowly, no hostility in his gate. He paused 10 paces from the porch. My daughter, he said in a voice like dry stone is inside. Thomas nodded once. She’s alive. The man closed his eyes just briefly.

Then he stepped forward again past the porch rail and into the cabin without waiting to be invited. Thomas followed but didn’t protest. Inside, the girl hadn’t stirred. The old warrior knelt by her side, laid a hand gently on her forehead. Then he looked back at Thomas, expression unreadable. You stitched her. I did. Fed her as much as she could take. The man studied him.

You took a risk. I saw a kid bleeding out. Didn’t feel like a decision. That apparently was the right answer. The old man stood. I am Huska, chief of the Tor Nili people. My daughter’s name is Atsa. Thomas glanced down at her. She didn’t say she would not, Haska said simply.

She was taken, fled, brought shame upon men who deserve none of her silence. He turned. You will ride with us, Thomas blinked. Ride where? We will speak of it on the trail. Thomas hesitated. The idea of leaving his cabin. of riding into the desert with 70 warriors didn’t sit easy. But he looked at the girl, Ata, and something in him twisted.

He had no daughter, no kin left in this world. But if he did, he’d want someone to help her without hesitation. “I’ll get my rifle,” he said quietly. The warriors waited in silence as Thomas saddled his horse. At was wrapped carefully in a blanket and placed on a travoir behind her father’s mount. Her breathing shallow but steady.

They rode east past the canyons and down into the valleys where the brush grew thick and the rock formations twisted like the bones of old giants. Haska didn’t speak much, but when he did, his words were sharp. She is strong, but there are those who would use her against me. Political enemies, men within and beyond the tribe. Thomas listened, didn’t interrupt. He knew the way the world worked.

Power always had a price, and sometimes that price came for your children. Around noon, they stopped at a red rock outcrop where a fire pit had been carved into the stone years ago. Warriors dismounted, moved like ghosts, all efficiency and silence. Thomas was offered water, food, even a fresh wrap of cloth for his horse’s ankle. Haska sat with him by the fire. You have no kin.

Not anymore. Then ride with us a while longer. Thomas didn’t ask why. He didn’t need to. As the sun dipped lower and the air turned cool, Haska told him the rest. At taken by a splinter group, a faction of warriors who believed the old ways had made them weak. that alliances with white settlers and treaties with Washington had only led to their people being scattered and broken.

They had taken at to send a message, but she escaped,” Haska said with pride in his voice. On a pony half blind and starved, she rode through the night. She was bleeding, but she rode. That night, the fire light cast long shadows over the canyon walls. Ata stirred once, her eyes fluttering open.

She saw Thomas and for the first time she spoke one word. Thank you. He nodded but didn’t say anything back. There wasn’t anything to say. The next morning they rode again. This time not away from trouble but toward it. By midm morning they passed the high messa where the scrub gave way to hardpan and dust devils spun like spirits caught between worlds.

Thomas rode third from the front now, flanked by two younger warriors who hadn’t said a word to him, but kept glancing his way as if trying to decide whether to trust a man who smelled of pine smoke and saddle oil instead of desert winds and dry sage. He didn’t blame them.

At slept in the travoir behind her father’s mount, and though her wound was bound and her lips no longer pale, her silence weighed heavier with every mile. They’d been riding east since dawn, Haska pushing them harder now that the sun was up and the distance still wide. The destination had not been spoken aloud, but the direction said enough. Thomas had heard of the place. A bend in the canyon wall near where the Santa Fe Trail split off.

Used to be a copper camp there, long since emptied and left to the hawks. “Why there?” he asked finally, his voice low. Hasker didn’t look back. Because they won’t expect me to come. That was all the answer he got. Two hours later, they reached the edge of the plateau where the earth fell away in jagged shelves.

Below, a thin thread of smoke rose against the sky, too steady to be from campfire alone. It curled like a question mark over the basin. Hasker signaled for the column to stop. He dismounted and walked to the edge, squinting through the haze. Thomas followed, crouching low to avoid the heat shimmer. There, tucked against the canyon wall, stood a cluster of leantos and canvas stretched across driftwood frames.

Six horses tied off to a post. Two men sitting by the fire. No centuries, no sign they expected company. They’ve grown careless, Haska said. Overconfident, Thomas replied. Or maybe it’s a trap. Everything is a trap, Huska said. But they have not yet heard she lived. Thomas scanned the ridge line.

How many down there? Four, maybe five, Haska said. But the others will be near. Two days ago, there were 13. Then we wait for night. Haskera shook his head. No, we send a message. He gave a short gesture and two of the younger warriors moved off silently, boughs slung over their backs. They’d circle around, position high, cover the entrance. What kind of message? Thomas asked.

But Hasker didn’t answer with words. He took the pendant from around his own neck, pressed it into Thomas’s hand. It was heavier than it looked, bronze, inset with obsidian. The symbol carved into it was older than any white man’s map. Ride with this alone. They’ll see it. They’ll know who you ride with. And when they try to gut me for it, don’t let them.

Thomas smirked, but the unease didn’t leave him. He slid the pendant over his neck and turned his horse down slope alone. Dust trailing behind him like a fuse waiting for spark. The ride into camp was slow, deliberate. He kept one hand loose on the rains, the other near the rifle slung across his back.

The men by the fire stood as he approached, their faces narrowing to suspicion the closer he came. One of them reached for his knife, but Thomas didn’t stop. I come from Husker, he said. I bring his words. The man with the knife stepped forward, thin, sharpeyed, his cheek marked with three deep scars. “You lie.” Thomas didn’t blink. Tell that to the men drawing bows on your scalp right now. It was a bluff, but only half of one.

He couldn’t see the archers, but he trusted. Has warriors knew their work. The man hesitated, then nodded once sharply toward the tent at the far end of the camp. Inside, Thomas dismounted and walked without flinching. Every muscle in his body told him to keep his back to a wall, but there were none here, only canvas and bluff.

The inside of the tent smelled like dust and sweat and meat too long on the fire. Two more men sat there, one older with a silver beard, braided to his chest. The other younger, face half shadowed. Both stared as he entered. I speak for Haska, Thomas said. You took his daughter. She lives. He rides with 70 warriors. He will speak with those willing to listen.

The rest he buries. The younger one leaned forward. She escaped. Thomas nodded once. On a half- deadad pony with a knife wound in her ribs. She made it. The old man said nothing. He just exhaled as if the wind had left his chest entirely. Then, without warning, he tossed something at Thomas’s feet.

A piece of cloth, torn, bloodied, her blouse. “This is what’s left of her place here,” the younger said. “She does not belong to Haska anymore. She belongs to what comes next.” Thomas didn’t flinch. He just stared back. “She belongs to no one.” The air thickened. A hand drifted toward a gun belt. Thomas didn’t move.

Tell him,” the old man said finally, “We will not run. If he wants blood, he can come for it.” Thomas nodded, turned, and walked out. Halfway back to his horse, he heard the shout, “Let him ride.” They didn’t follow. He rode hard back to the ridge. “Has waited with arms crossed. Behind him, the warriors had spread out across the stone like storm clouds about to break.

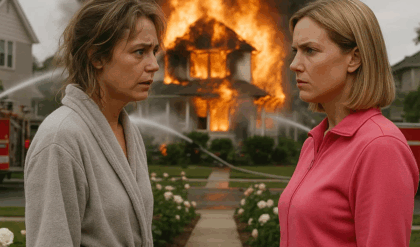

He said what I expected, Haska said after hearing the report. Thomas handed back the pendant. Then what now? We draw them into the open. How they believe they can stand behind shadows, Haska said. We burn the shadows away, he pointed. Warriors moved. Torches lit. Flames roared. They didn’t ride down to the camp.

They rode past it high on the ridge, lighting the dry brush and sending fire cascading down like a wave of orange teeth. Smoke curled fast. By the time the fire reached the edge of the canyon floor, it was a wall. The men in the camp scattered, shouting, coughing. Horses screamed. Tents caught.

Flames reached the copper still at the far end and lit it like an oil lamp. The boom echoed for miles. Out of the smoke ran six men only six. The rest were likely gone or dead or buried under caved in canvas. Hasker gave no order. The warriors loosed arrows. Four dropped. Two ran. Thomas didn’t draw. He just watched. One of the runners was the young man from the tent.

The other scarred cheek knife still in hand. Thomas kicked his horse. He rode down fast, straight into the smoke, cut across the canyon, eyes stinging. He caught the scarred one at the edge of the old copper pit. The man turned, swung the knife. Thomas ducked, rammed his shoulder into the man’s chest, and both went tumbling. They rolled hard. Dust, blood, grit.

The knife skittered away. Thomas pinned him. You took her. The man spat blood. She was leverage. She’s a child. She’s power. Thomas drove his fist once. The man didn’t move again. When he rose, the fire had burned down. Haska stood at the ridge, watching the camp smolder.

Warriors picked through the ruins, retrieving weapons, scattering embers. At sat upright in the Travoir, watching too. Her eyes found Thomas. She didn’t smile, but she didn’t look away either. The canyon smoldered behind them like a quarterized wound, red embers still twitching in the night breeze. It would take days for the smoke to clear from the high basin. Longer still for the charred scent to drift from memory.

But Hasker had done what he set out to do. The message was sent, and the silence that followed said more than any war cry. They made camp far enough east that the glow of the ruins no longer touched the sky. a narrow hollow near a dry wash, quiet, say for the cicardas. No fire, just cold bread, water, and a circle of warriors that did not speak unless necessary.

Thomas sat near the girl again, not too close, just enough that she could see he hadn’t left. Her eyes flicked toward him now and then, never more than a second, but it was more than before. Hasker was sharpening a bone-handled knife by firelight that didn’t exist, letting the sound of stone against steel be his voice. He hadn’t spoken since sundown. Neither had most of the men.

There was a tension in the quiet now, one that hadn’t been there earlier. They’d won, yes, but not the kind that brings relief, only the kind that buys time. The old warrior named Shitani broke the silence first. He’d been one of the first to arrive that morning, the first to dismount beside Atsa.

His beard was thin, mostly white, and he moved like someone whose bones remembered more winters than his tongue could count. He stepped into the circle and crouched low, letting his palm press into the dirt. “Seven men dead,” he said. “Three of them known, four not.” He didn’t look up. Just let the facts fall like pebbles into the center. the ones not known.

They had no markings, no clan, no name in the winds. They were not born of the people. There was a shift then. Heads turned. Some murmured. Hasker didn’t react. He kept sharpening the blade. Thomas looked at him. Mercenaries. Haska nodded. Just once. They’re hiring outside muscle now. They’re building something. Haska said. They’ve been gathering to the south. small at first, then more.

They don’t care if the men they bring know the lands, only that they obey. They’re looking for something, Shitani added. Or hiding it. Either way, said Huska. They’re readying for war. The word hit hard, even among warriors. Ata stirred. All eyes turned to her. She didn’t speak, but she leaned forward and reached into her side pouch.

From it she pulled a stone, smooth, black, shaped like an almond. She held it flat in her palm, arm extended for all to see. Shitani hissed softly. “Where did she get that?” “She took it from their camp,” Thomas answered before she could. “Just before the fires.” She held it the whole way back. “It’s not just stone,” another warrior said.

“That is shaped, that is carved. It was a small etching along the side, barely visible except under moonlight. A spiral that looped outward and then inward again. Ancient, older than the tribes. They found something, Haska said, finally slipping the blade into its sheath. And they needed her to open it. A murmur again. Sharper this time.

Thomas frowned. What do you mean open it? She carries blood. Haska said. Not just mine. Her mother was daughter to the moon singers. That blood remembers things. Unlocks them. You think they were trying to use her? I think they already tried. And she ran. No one spoke for a long moment.

Then Thomas said quietly, “Where does the spiral lead?” At looked at him, then down at the stone. She pointed south. A direction none of them liked. That night, while the others slept or sat quietly with thoughts folded like blankets, Haskera came to Thomas’s side. “You saved her,” he said simply. “I found her. You pulled the knife from her. Gave her your water. Risked your home,” Thomas shrugged. “Didn’t know who she was.

” “You still don’t.” Has sat beside him, eyes scanning the darkness. “She is my daughter, yes, but she is also more. There are stories told among our people, old ones of children born under certain moons. Ones who do not cry at birth, who hold their breath till the hawks circle and only then exhale.

Thomas glanced at her, who now lay curled beside her blanket, eyes open, but still. She never cried when they took her, Haska said. Not once. He turned and for a moment the fire of a memory flickered across his face. They came in the night. Six riders. They knew where to go, who to bind first. Her mother died before I could return. They were gone by the time I reached the ridge.

But they’d left behind signs, symbols carved into the stones, the spiral, and something written in a tongue I’d seen only once before. “What did it say?” Thomas asked. “Blood knows the gate.” The air felt colder then. We thought it was a warning, Haska said. Now I think it was a map. Thomas stared at the horizon. So where do we go? We follow the spiral. The decision was made before the sun rose.

They packed light, water, dried meat, arrows, two rifles. At rode behind her father again, but this time she sat upright, her small hands holding the res though they were her own. They passed the old stone to Shitani, who tied it to his belt like a charm. The older man rode at the front, guiding them toward a pass few remembered. It wasn’t marked on maps. It didn’t appear in stories told to white men.

It cut through a ravine black with ash, bordered by cliffs shaped like skulls. On the second day, the trail narrowed and the wind changed. Even the birds stopped calling. Thomas rode beside Hasker again. “Whatever they’re hiding,” he said. “They’ve gone to great lengths to keep it buried.” “Yes,” Haska said. “Which means it’s worth digging up,” they found the first marker near dusk.

A can of stones stacked seven high, each one painted with pitch, smelling faintly of copper and burnt oil. The spiral was etched into the top stone. The same etching as on the stone Atza carried. “They’ve been here,” Thomas said. “Not just them,” Shitani replied.

He crouched near the stones, sifting dust with his fingers. “Something else passed through. Something heavier.” Thomas looked at the trail. “Wagon, too,” Shitani said. “Iron rimmed eastbound. The path grew stranger after that. Cracked earth gave way to salt crust. The plants turned white, brittle. Even the cactus seemed to lean away from the trail as they passed.

Atsa spoke for the first time just before sunset. She pointed ahead and said one word. Ashihi. Haska froze. You’re sure? She nodded. Thomas looked between them. What does it mean? It’s not a word, Haska said. It’s a place, a crater, older than any story we still tell. And why go there? Because that’s where the dead wait.

That night, they camped just outside the crater’s edge. A wide hollow, deeper than a canyon, but ringed with stone, like some great bowl left behind by forgotten gods. The stars above were clearer than any Thomas had ever seen, cold and watching. At the bottom of the crater sat a shape, a structure, not a cave, not a ruin, something different.

It pulsed faintly, and as Thomas stared, he realized it wasn’t just reflecting the moonlight. It was breathing. They approached the edge of the crater in silence. The wind didn’t reach them here. It sank instead, pulled down by some unseen gravity that seemed to gather at the basin’s heart. Horses refused to descend. Their legs stiffened, nostrils flared. Even Haskera’s black stallion poured the ground and backed away from the rim.

“We go on foot,” Sheani said. Thomas took one look at the sloping descent, then at the strange shimmer in the air near the crater’s center. “What is that?” he asked. “Heat,” Haskera said. But his voice lacked certainty. or something older.

They tethered the horses beneath a rocky overhang out of sight from above, though the nearest trail hadn’t seen footprints in years. At handed her stone to Shitani, who slipped it into a worn pouch at his side, and they began the descent. Thomas, Huska, Ata, Shitani, and four others chosen for silence and steel. The ground changed fast from dirt to compacted dust. Then to something harder, stranger rock that seemed too smooth, glassy in places.

Thomas kicked a small fragment loose. It slid farther than it should have, spinning once before it stopped on its own. Volcanic? He asked. No, Shitani said. Something else burned from the inside. Halfway down, Ata paused. She bent low and pressed her hand against the earth. Fingers spled wide. Her lips moved though no sound came.

Husker stepped beside her. Nelt and placed his palm beside hers. A stillness passed between them. Something Thomas could feel but didn’t understand. The air vibrated faintly, like a distant hum pressing behind his teeth. Then the girl opened her eyes. There’s a door, she said. Those were her exact words.

They came like a knife through fog, sudden and sharp, not whispered, not timid. Has didn’t flinch. Where? At turned, pointed toward the center of the basin. Beneath the stone that breathes. Thomas narrowed his eyes. The structure at the bottom looked almost natural, like an outcropping of fused rock. But now he saw the pattern. The unnatural symmetry.

The way the stone pulsed every few seconds. Not like breathing, but like a heartbeat. Slow, steady, ancient. As they moved closer, the heat thickened. Not from the sun. It was long gone. But from something internal, like standing near a forge you couldn’t see. The others drew scarves over their faces. Thomas did the same.

Even Atera, who didn’t seem to mind the heat, wiped sweat from her brow. At the edge of the structure, they found carvings not etched with tools, but melted in spirals again, interlocking, endless. At stepped forward and laid her palm against the surface, the stone side, that’s the only word for it. A long exhale, slow and deep. The pulse quickened once, then again. Then the surface rippled and pulled back like retreating skin.

Behind it, darkness, a tunnel sloped downward, wide enough for one man at a time. No light within. No breeze, just an airless stillness that pressed against them like water. Shitani lit a torch. The flame burned blue. “That’s not right,” Thomas muttered. No, Hasker agreed. It isn’t. Still, they entered. The descent was steep.

The walls curved inward. There were no markings down here, no decoration, no texture, just that same black stone, fused and warm. The deeper they went, the less the torch helped. The flame bent strangely. Shadows clung to corners where none should exist. It took nearly 10 minutes before the tunnel widened. The chamber they stepped into wasn’t large, but it felt vast.

Not by size, but by presence. Something filled it that had no name. At the far end stood a pedestal. Upon it a second stone identical to the one Ata had carried. Shitani moved forward, but Ata stopped him. She walked past the others, reached up and took the stone in her hands. The pedestal shivered, and the walls groaned.

Suddenly, spirals lit across the chamber walls, glowing faintly with a soft green light. The temperature dropped. Thomas could see his breath. Then, a voice echoed. Not in English, not in Navajo, not in any tongue Thomas had ever heard, but the cadence. It wasn’t angry. It wasn’t welcoming either, just curious. At stared into the stone, her mouth opened. “She’s listening,” Haskera whispered.

“To something we can’t hear,” Thomas stepped back. “Should we stop her?” “She was born for this.” The girl knelt, placed the stone beside the first in her pouch. And for a moment, the pulsing heartbeat stopped. Silence. True silence. Then came the footsteps. Heavy, distant, echoing down the same tunnel they’d come through. Husker drew his knife. Shitani unslung his bow.

Thomas raised his rifle and backed toward the entrance. They weren’t alone. Ata didn’t flinch. She stood slowly, her eyes still on the pedestal. The tunnel trembled. Then they saw it. Light bending around something massive. A shimmer, a distortion, like a mirage made flesh. A man stepped into view. But he wasn’t a man. Too tall. Skin pale as bone.

Eyes black, not from lack of light, but because they were never meant to reflect it. He wore no clothes. just layers of woven cords that dangled from his shoulders like a shaman’s robe. He stared at, then at Thomas, then he spoke. The words weren’t human, but Thomas heard them in his bones. The meaning flooded his head like heatstroke. She has two. Bring the third. Then the figure turned and vanished down the tunnel from which it came. Silence again.

Ata turned to Hasker. I know where it is, she said. He didn’t ask how. He only nodded. They left the chamber quickly, careful not to touch the walls. When they emerged into the night, the air felt thinner, like it had been drained and returned. The horses were gone. Tracks led away, deep and erratic. One of the scouts ran up from the east ridge, panting.

Riders, he said. North Trail. At least a dozen cavalry colors. Blue coats, Thomas asked. The scout nodded. We need to move. They set off on foot toward a ravine that wound eastward into higher country. If Ata was right, and she usually was, the third stone lay somewhere in the bones of the abandoned mission near Tres Lagonas.

An old Spanish outpost turned trading post turned ruin. The kind of place even scavengers avoided. But before they reached it, they needed shelter. A storm gathered in the west, sudden and wrong. Lightning flashing without thunder. By dawn, they reached an overhang and settled into a narrow ledge beneath. Rain hit the canyon in sheets, filling the wash below in minutes.

Flash floods tore through the lands, but they were safe for now. Has kept watch. Thomas sat beside Atser. “You knew he’d be there.” He said quietly. “I saw him in the dream,” she replied. “Was that man alive?” “No,” she said. “Not anymore.” She didn’t elaborate. Below them, the water churned red with clay and runoff, and in the distance, thunder began to speak, not in cracks, but in long rolls, like a drum beat coming closer.

They left the canyon before the floodwaters could recede. The storm passed during the night, but its memory lingered in the deep grooves it left behind. Furrowed earth, fallen boulders, a landscape reshaped in hours. The air smelled like iron and ash. Every step they took forward was muffled by the soden soil beneath their boots. Thomas had traveled to Tres Lagonas once, long ago.

He’d been escorting a silver prospector, some idiot with more confidence than sense, through Apache country, and remembered the ruins only because they didn’t feel like ruins, not broken enough to be dead, not intact enough to be alive. The place had teeth. They approached from the east slope as sun broke through the clouds. The mission came into view slowly. First the bell tower, jagged and leaning.

Then the arches, three of them still intact. Then the well, the center of it all, sealed shut with iron bars, the kind thick enough to hold in something that didn’t want to stay buried. The girl led the way. At hesitate, she didn’t need to search. She walked past the shattered front doors, beneath a sagging beam, into the collapsed sanctuary where broken pews lay scattered like bones.

Beneath the altar, there was a hatch halfcovered with debris. She knelt, brushed aside a thick layer of dirt and ash, and uncovered a rusted iron ring. Shitani helped her pull. The wood shrieked. A staircase spiral down, narrow and dark. No torches, said. Thomas stopped mid-motion. Why? It’s not darkness you need to see through. It’s what waits in it. Haska nodded.

We go without flame. So they did. The descent was worse than the one into the crater. The walls here weren’t stone. They were carved from packed earth, held in place by old timbers. Wetness clung to everything. Mold, stagnation, the smell of long decayed paper. When they reached the bottom, the tunnel widened into an anti-chamber. Shelves lined the walls, what was left of them.

Most were collapsed, but some still held scrolls, jars, books sealed with wax, bones wrapped in linen. And in the center sat a man. He wasn’t breathing. He hadn’t breathed in years. But he was upright, arms crossed, skin stretched tight over his frame like leather left too long in the sun. His eyes were gone, but his sockets stared at them, accusing.

Atsa walked forward, knelt, and spoke in a voice that did not belong to her. It was a language Thomas had never heard. Not Navajo, not Spanish, not any tongue still spoken. The corpse twitched. It moved its right hand slowly, fingers creaking like dried branches. Then it opened its palm. There lay the third stone, identical in shape, different in pattern.

Atsa took it with both hands and bowed her head. The corpse collapsed into dust. Not slowly, all at once. The moment she lifted the stone, whatever thread had kept it whole, dissolved. Bones crumbled, robes deflated. What remained was a thin layer of powder, disturbed only by their breath. Thomas didn’t speak. No one did.

They ascended the stairs, stepped back into the light, and the sun seemed too bright, too real, the air too loud. Outside, something waited. The rider sat on a pale horse. His coat was union blue, long and worn, but his insignia was wrong. Too many bars, too many medals. They glittered unnaturally, like they weren’t made of metal.

Behind him, soldiers, 20, maybe more. All still, all silent, their rifles pointed down, not raised, but ready. The leader looked at Thomas, then at then he smiled. His teeth were black. You have the third, he said. At stepped forward, stone in hand. The man dismounted. He didn’t walk like a man. He glided, and as he came closer, Thomas saw the truth.

His boots didn’t touch the ground. “Give it to me, girl,” he said. “You don’t know what you carry.” “She knows,” Haska answered. The man’s smile widened. “You’ll die for her.” “No,” Haska said. “We’ll die with her.” Then came the whistle. Hi, sharp from the ridgeeline. 70 warriors appeared in silence. Navajo. Not screaming, not charging, just present.

The way a storm is present before it breaks. The false cavalry turned and ran. Not all of them. Half disappeared into smoke. The rest turned physical. Bullets and blood. The fight wasn’t long. Rifles cracked. Arrows flew. By the time Thomas could raise his Winchester, it was already over. The pale horse stood alone.

Its rider was gone. Only his coat remained, folded neatly on the ground. Ata picked it up, turned it over, and pulled a final trinket from the inside pocket. A key bone carved marked with spirals. Shitani touched the stones in her pouch. They are calling to each other, he said. Three is not enough. There’s a fourth, said. Thomas swore. Of course there is.

The warriors said nothing, but their leader stepped forward. At’s father, he looked down at her. No smile, no scorn, only understanding. You heard the path. She nodded. I will go with you. That was all. No ceremony, no preparation, just direction. They turned toward the northeast, toward the ancient ground near Red Bluff Canyon, a place the Navajo avoided, a place even the Apache named with curses. It was said the dead did not stay dead there.

As they moved, Thomas asked her the question he’d been biting back. “Ata,” he said. “What happens if someone brings all four stones together? She looked at him, then passed him, and said nothing.” But her silence said more than words ever could. It said, “You’ll find out soon.” The journey to Red Bluff Canyon was one of silence, not out of strategy or secrecy, but necessity. Words felt heavier the closer they drew.

Even the wind held its breath. They moved in pairs now. Thomas and Atok with Hasker riding close behind. The warriors fanned out at a distance, but never far. Shitani hung back often, stopping to press his hand to the ground, eyes closed as if listening. He said nothing of what he heard, but twice he told them to change course, even when the trail was clear.

Thomas stopped questioning it. There were things here he couldn’t see. The old man could. The sun didn’t set the way it usually did. It faded like memory gradually until they were riding under a sky too dark for twilight and too quiet for night. They made camp only once, no fire, just rations and water, and the constant sense that something watched from beyond the yuckers and split rocks.

The stars gave no comfort. They blinked without warmth. No one slept. By dawn, Red Bluff’s rgeline appeared. not rising like a normal canyon wall, but erupting. The entire formation looked wounded, torn from beneath the crust like a broken tooth forced upward, red strata bled into orange, then brown like dried rust. No trails led in.

No known ones anyway, but Ata knew. She walked now, even though the horses could still go further. She pointed to a narrow cliff between two slabs, too thin for a man, but not for a girl. I’ll go first, she said. No, Thomas said, we go together. Her father, quiet until now, nodded. She leads, we follow. So Thomas did.

He unstrapped his rifle, tied the horse to a crooked juniper, and stepped into the crevice behind her. The rock closed around them like a throat. The way narrowed, then opened again into a hidden hollow carved by wind and time. A hollow so precise it looked shaped, not natural. There were markings, petroglyphs, but deeper, angrier, not etched, but clawed.

Spirals, animals, hands with two, many fingers. One figure repeated often, a faceless man with a long body and no legs, just roots, hundreds of them, spreading like veins across the stone. Shitani froze when he saw it. It’s him. Who? The one beneath. They passed under a stone arch and beyond it nothing. An open field, flat, dead, no brush, no birds, just white soil cracked like a sunburnt lake bed. But Ata didn’t stop.

She walked to the center where four stones jutted from the ground in a square pattern, each identical in size and shape. She knelt, opened her pouch, and removed the three stones she carried. She set them on three corners. Then she placed the fourth from her father’s hands. Silence, then thunder. But the sky was clear. The earth beneath them began to hum.

The four stones glowed faintly, then brighter. The cracks in the soil widened. A massive slab in the center split open with a sound like snapping bone. Dust flew outward in a slow spiral, and from beneath the ground rose a shape, not a person, not quite. It had a body, limbs, but they were too long, bent wrong, as if joints had been added and some removed.

Its face was covered by a mask, stone, carved, too heavy to wear, yet fused to its head. It said nothing, but all of them heard the voice. You woke me, trembled, not with fear, but recognition. This is what was sealed, she whispered. Not just the stones, him. The warriors readied weapons. Too late. The thing moved.

Not fast, but not slow either. A kind of inevitability, like flood water. It raised one hand, and the ground answered, rising beneath it in a surge of white dust and stone. Shapes formed. More figures bound to it. Specters, but real. One tackled a warrior. Another lunged for Shitani, who raised his staff and screamed something guttural.

The creature paused, writhed, then exploded into ash. That gave them a chance. Thomas fired. The shot hit square in the mask. The figure staggered, but only for a breath. Then it turned to him, and beneath the mask, something opened. Not eyes, not a mouth, just void. He nearly dropped the rifle. Haska shouted for retreat, but the canyon walls began shifting, slabs twisting inward like jaws closing. They were trapped.

Then at something no one expected. She walked forward, hands raised, stones in her palms. The thing paused the others, the specters stopped too. She spoke not in her voice, not her words. We are not your jailers. We are what remembers you. The ground stilled. The wind returned. Time slowed. Then, in a movement that seemed almost gentle, the creature knelt and crumbled, not into ash, but into soil, rich, black, living. The stones in her hand cracked.

The pieces fell to the earth and disappeared. All four gone. And the canyon went silent. Truly silent. The kind that comes after something old finishes breathing. They stood in that silence for what felt like hours. Then her father turned to Thomas. You saw what she is. She’s not a child. No. Is she? He didn’t finish. She is what they need her to be.

Atsa stood quiet. She walked back toward the arch. Everyone followed. At the edge of the canyon, they paused. The sky looked different. Cleaner, but not safe. Thomas adjusted his rifle, looked to the trail ahead, and exhaled. Where to now? At look at him when she answered, but her voice was clear. There’s still one more who remembers, and he’s not buried.

The trail out of Red Bluff Canyon was slower than their descent in. No one spoke much, not because there wasn’t anything to say, but because everything had changed, and the weight of that hadn’t settled yet. At rode in silence, her posture straighter now, not from pride, but something more ancient, as if her bones had learned how to carry things older than fear.

Shitani, for all his age and knowledge, kept his distance from her, not out of fear, but reverence. The warriors glanced her way often, but didn’t crowd her. They had seen what she’d done. They had seen what she was. That kind of thing didn’t need talking over. Only Thomas still wrestled with it. He hadn’t spoken much since the creature fell back into dust.

And even now, as he rode beside her, he wasn’t sure if she was a girl he’d saved or something else entirely. But he didn’t press. Some truths you waited for, not demanded. They didn’t return to the homestead. They didn’t stop in any known town, Ata said, where they needed to go. And Hasker only nodded. So they headed west, deeper into land that didn’t belong to anyone anymore.

Past the stone markers no one carved. past the wells filled with sand and fences snapped like bones. The air grew dry, then thicker. Even the sky dulled, not with clouds, just a colorless weight that flattened the horizon until everything felt like memory. They found the town at dusk. It had no name, no signs, just the ruins of structures half buried in red dust, a steeple broken in half, a well choked with weeds, doors hanging open, some without buildings attached, no birds, no wind. The air didn’t move. It clung. At

dismounted first. This is where he went, she nodded. Thomas adjusted the rifle, slung at his back, and followed her through the skeletal remains of the town. The others spread out, watching the edges. It didn’t take long. They found the man in what had once been a church, now barely more than splintered benches, and a sagging frame.

He sat at the far end where the altar had been, head bowed, hands resting in his lap, the last of the light catching the silver in his beard. He looked up when Atza stepped inside. His eyes were milky, not blind, just pale like everything else. “Here, you came?” he said, his voice carried like it hadn’t been used in years. I was waiting. Thomas stepped forward.

“You’re the survivor.” The man didn’t answer. He looked only at saw you once when you were very small before the stones broke. Your mother brought you to the line and told me your name. At’s face didn’t change. What happened here? He smiled. What always happens? Men dig. They don’t like what they find, so they bury it again. Then they forget the holes still there. She stepped closer.

You know who I carry? He nodded. Not the name, but the weight. Yes. They want to bury it again. They always do. Should I let them? He looked up at the beams above where bits of the fading sky leaked through. No. Then he stood. He wasn’t tall. But the room felt smaller now, more solid, like time had collapsed inward. You need to finish what your mother started.

She died for it, and you might, too. He reached into the pocket of a long coat and pulled out something wrapped in cloth. He handed it to her. Thomas stepped forward instinctively. What is it? The man looked at him for the first time. Your part is done, Ryder. She’s just a girl. She was, he agreed. Not anymore. At unwrap the cloth. She just held it, then turned and walked out.

The man watched her go. You kept her alive. For that, I thank you. Thomas hesitated. What’s in the cloth? The old man smiled. The memory of a promise. Then he sat back down where they’d found him and closed his eyes. Thomas stared, waiting, but the man didn’t move again. Outside the sky cracked, not with thunder. With light, the kind that doesn’t blink.

At stood in the center of what had once been the town square. The other warriors had circled around her, not too close. Hasker stepped forward. “Is it time?” she nodded. She handed him the cloth. He didn’t unwrap it either. He just held it, then knelt and began drawing in the dust with his fingers.

Circles, not perfect, not sacred, just remembered. The other warriors joined him together. They trace symbols, old ones, before letters, before language. They didn’t chant, they didn’t speak, they just worked fast like they done it a 100 times before. Thomas stood at the edge, unsure. Then Shitani put a hand on his shoulder. This is where you watch.

He did. As the last line was drawn, Ata stepped into the center. Haska placed the wrapped object on the ground. She knelt beside it, removed the cloth. Inside was a bone, but not just bone. Carved, painted, a totem. It pulsed, then it cracked. A sound like a thousand screams swallowed the silence. From the ground rose the wind, real wind.

But it carried voices, songs, warnings, names. The dust lifted in a column circling Atsa. The warriors did not run. They bowed their heads. At stood, arms spread, and the totem burned. No flame, no smoke, just light. It surged outward. A wave that passed through everything. Thomas, the old church, the sky itself.

For a moment, the world flashed white. Then it was gone. The town stood still, but not dead. Grass poked through the cracks. The wind returned. Real wind this time with scent. Birds circled. The church beams didn’t sag as much. At stepped out of the circle, the totem now just ash in her palm. It’s done, she said.

Thomas looked at the others. At the world. What did you do? She looked at him. Not as a child, not even as a protector. Just herself. I remembered what they forgot that night. They didn’t camp. They didn’t sleep. They sat together around the first fire in days. At said little, but she didn’t need to anymore. The dead had stopped whispering.

The living could finally speak again. By morning, the warriors would ride east, back to their land, back to what waited next. At would ride with them. Thomas would not. He stood beside the well as the sun climbed the sky pack slung rifle strapped. Hasker approached. You could come. Thomas shook his head. I’ve seen enough. Haska nodded. Then may your trail stay clear. They didn’t say goodbye. Just a clasp of hands.

At say anything either, but she smiled. That was enough. As the horses thundered east, Thomas turned west. He didn’t know what lay beyond the ridgeeline, but the world had shifted and the dead were finally at peace.