HOA Started Building on My Ranch—They Ran Crying When We Showed Up Armed!

When you own over 3,000 acres of Texas land, you learn to stop worrying about every twig that snaps in the woods. Between the mosquite trees, wild hogs, rattlesnakes, and the occasional overconfident coyote, life out here stays noisy in all the right ways. But that week, that week was supposed to be quiet. I was headed to Austin for the Lonear Agri Summit.

10 days of new tech, new cattle genetics, and a whole lot of barbecue fueled handshaking. I left the ranch under the watchful gaze of Miller security systems. A Frankenstein beast of drones, motion sensors, and ground cameras my buddy Tyler helped me install last fall.

The north entrance had a proper gate with reinforced steel posts and RFID badge access. the southern end. Well, that part of the property was a dense stretch of woodland and creek land that hadn’t seen a bootprint in weeks. No one came through the south edge. No one needed to. Not unless they wanted to be eaten alive by brush thorns, snakes, or my late uncle’s paranoia, which now lived on as several well-hidden motion detectors nailed to trees.

I left Rick in charge of airfield maintenance and took my leave, not thinking twice about the treeine that separated my land from the gleaming new subdivision next door, Cedar Crest Ridge, a place so upscale it probably required residents to brush their dog’s teeth twice daily. Their HOA president, a smug bastard named Chad Strongwell, had once tried to hand me a Cedar Crest newsletter at the feed store. I handed it back without looking.

We didn’t have much in common, him and me. I build fences. He builds committees. So, you can imagine my lack of concern as I drove out sipping coffee, thinking only about which new pasture management software I’d demo first. My land was locked down tighter than Fort Knox, or so I believed.

The southern boundary was marked, logged, and documented in every possible way. And hell, I hadn’t even driven that direction in months. Too overgrown, too boring. On day three of the summit, I got the first ping. Movement detected. Zone S17. At first, I figured it was a deer. Happens all the time.

The motion triggered camera would probably show a dough nosing through the underbrush. But when I opened the app and pulled up the feed, my jaw clenched so hard I nearly cracked a moler. A bulldozer, not a deer. A godamned caterpillar dozer, yellow and loud, trundling down what used to be a natural oak belt near the southern creek.

Behind it, two work trucks and a godless mess of orange plastic fencing. One of the workers waved someone through what appeared to be a brand new gravel ramp cutting up the slope. A ramp that hadn’t existed 48 hours ago. They were building something on my land. I thumbmed through the other feeds in a flurry. Zone S18, S19, S20, all lit up like a Christmas tree.

Earth movers, stakes, utility trailers, porta johns. These weren’t pranksters. This was a crew and they looked settled in. My gut twisted the way it used to before a raid. I called Tyler, Rick, and Jason. Saddle up. I’m flying home tonight. They didn’t ask questions. They just said, “How many clips?” I left the summit with a half-finished rib and a full tank of vengeance. As the plane climbed into the clouds, I pulled up the satellite overlay.

The bastards had cleared out a chunk of my woods, roughly 70 to 80 yards deep, and were moving west. A tent labeled sight office, sat right in the middle, complete with a popup banner that read, “Future home of Cedar Crest Ridge Private Clubhouse.” You’ve got to be kidding me. Chad Strongwell, in all his real estate glory, had apparently decided that because my southern fence line was hard to reach, it didn’t count.

He probably thought no one had noticed if he carved off a few dozen acres of unused land and tossed in a helipad for his rich buddies. Well, now he had my attention. As the sun set over the plains beneath me, I imagined his smirk, his spreadsheet, his quiet assumption that rural meant weak, that cowboy meant ignorant, that some rancher wouldn’t care. He had no idea who the hell he was dealing with.

I texted the sheriff and said I’d need a unit on standby in 48 hours. I texted my lawyer and told her to find the property deeds. And then I stared out the window as the clouds turned crimson. This was still Texas. And out here we don’t ask permission to defend what’s ours. We landed just after 2 in the morning.

wheels hitting the dirt strip of my private airfield with that familiar bounce I could almost feel in my spine. Jason was already waiting with the Jeep, headlights casting long twitchy shadows over the hangar. He tossed me a thermos of black coffee. No words needed. We’d been through worse together. Fallujah Mosul, but this was personal.

As we tore down the north trail, Rick radioed in. They’ve poured concrete foundations, Cody. I counted at least 16 workers this afternoon, plus a stack of steel beams and what looks like temporary plumbing. I tightened my grip on the roll bar. Still on our land. 80 yards past the fence. South oak belts torn to shreds. Copy that.

We stopped at the armory, which granted was technically a glorified storage barn, and each of us strapped on our rigs. I took my AR slung across the back, sidearm on my hip, and slipped a flash drive into my shirt pocket. It held all the footage from the last 72 hours. Jason brought his drone. Tyler grabbed the tablet linked to our perimeter motion sensors.

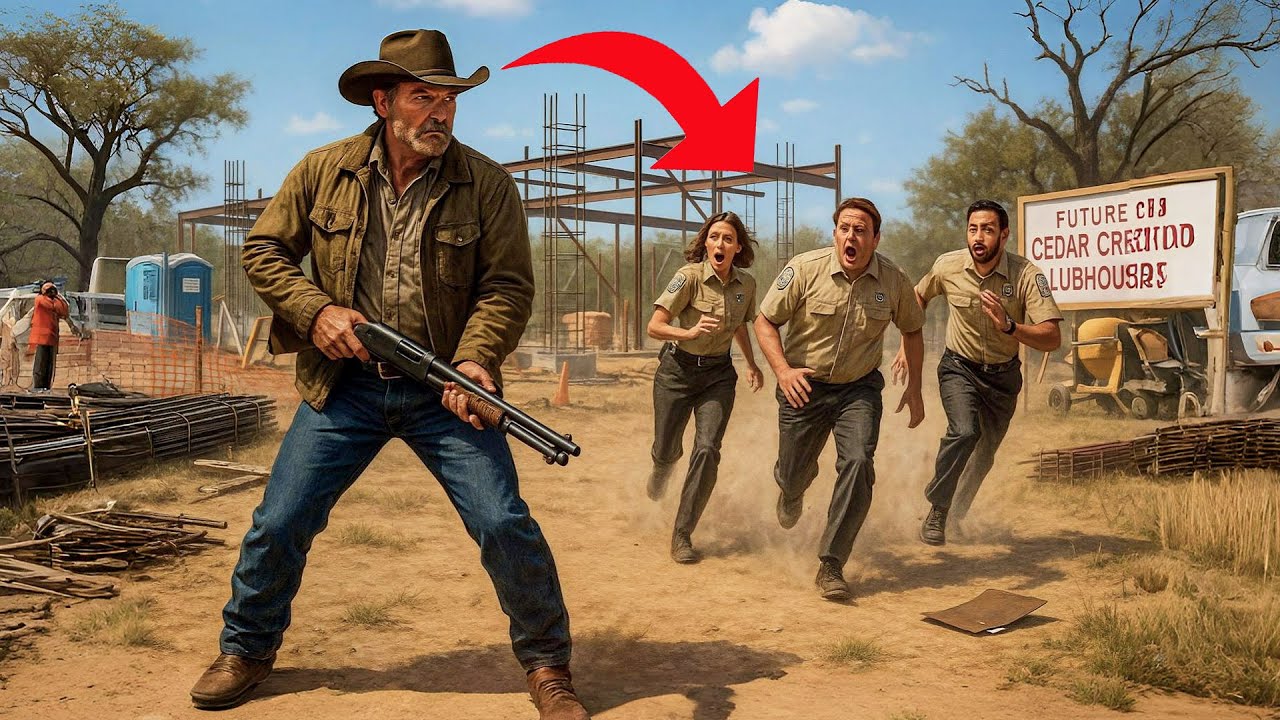

Sunrise wasn’t far. I figured we’d give them the show they were clearly asking for. We rolled out at first light. Four ex-marines in one dusty Wrangler. Guns visible but slung safe. Badges clipped to our belts. Legally armed, legally pissed. The road down to the southern treeine had been expanded poorly and freshly scraped tire tracks told the rest of the story. They hadn’t just entered.

They’d built a godamn road through my forest. The clearing was worse than I imagined. Steel frames rose like bones from raw dirt. Orange vests buzzed around like fire ants stringing rebar hammering stakes. There were trailers with air conditioning units, coffee stations, coolers, a full-on job site. On my ranch, I rolled up slow and parked 30 ft from the nearest crew.

A young guy in a hard hat glanced up, then froze when he saw us step out. “Morning,” I called, nice and calm. “Mind telling me who gave you permission to build on private land?” His face pald. He reached for his walkie-talkie. Rick walked forward and planted a surveyor’s stake right in front of the bulldozer. County line ends 74 yards behind you. This is private property.

Y’all are trespassing. Another worker bolted inside the trailer. A minute later, out came a guy in khakis and sunglasses, probably mid-40s, clearly not used to being questioned before noon. I’m site manager Kevin Barnes, he started. We’ve got permits filed with Cedar Crest Ridge, which has zero jurisdiction here. I cut in. This land is owned by me, Cody Miller.

Deeds filed with Hamilton County. Want to see it? He blinked. That can’t be right. Jason powered up the drone and let it hover 10 ft above, panning the scene. It’s right, he said. You’re 83 yd inside Cody’s property line. We’ve got aerial, GPS, and perimeter sensor data to prove it. Kevin swallowed. Let me call Mr.

Strongwell. You’ve got 10 minutes, I said. Then I call the sheriff. And I did. I made sure Kevin heard the entire conversation as I called up Sheriff Lenny Harper. Hey Lenny, I’ve got a work site violation on my property, trespassing, destruction of vegetation, possible illegal waste dumping. You sending a unit. Be there in 20, he said.

Don’t shoot anyone? No promises. By then, word had spread. Half the crew had vanished behind trailers. One guy filmed us on his phone from behind a stack of cement bags. Another started backing a bobcat toward the treeine like maybe that had undo the last three days. Kevin’s phone rang. He stepped away to answer. Hold your position.

We heard him hiss. It’s all a misunderstanding. Tell the sheriff it’s an easement issue. I’ll get it sorted. Do not engage. Too late. Sheriff Harper arrived with one deputy, lights flashing, tires crunching gravel. He stepped out, took one look at me and my crew, then turned to Kevin. You the one in charge here? Kevin hesitated. I I’m the site manager. Yes.

Do you have a permit from the county? No, but then you’re under arrest for unlawful construction and criminal trespass. Step over here. The deputy cuffed him right in front of the portagon. I almost felt bad. Almost. Two more guys were detained when they tried to slip away in a van. The sheriff’s office would process them later. I walked to the center of the clearing, the place where my grandfather once planted the first live oak that grew this grove. Nothing left now but mud and rebar.

“Pack it up,” I told the workers still standing around. This project’s dead. And just like that, they started moving. Quiet, ashamed. I didn’t scream, didn’t curse, didn’t make a speech. I just stood there as the Texas wind blew dust across the wreckage of someone else’s fantasy. Two days later, I was in a conference room with my attorney, Gina Horton, sorting through aerial photos, property deeds, and topographic maps older than I was. The office smelled like lemon cleaner and old law books.

Gina didn’t waste words. She pointed at a printout of the Cedar Crest Ridge development plan, highlighted in blue. “See this,” she said, tapping the southern border. They marked your land as undeveloped municipal green space. I blinked. Municipal? My family’s owned that land since 1957. She nodded. That’s the problem.

Strongwell submitted this to the planning committee last quarter. Claimed the parcel was vacant surplus from the original Cedar Ridge plat. They didn’t check because he has friends on the zoning board. I leaned back in the chair, staring at the ceiling. Let me guess. He thought if he poured concrete fast enough, nobody’d challenge it. Exactly.

But he picked the wrong rancher. That afternoon, I filed a formal civil claim against Cedar Crest Ridge HOA and Chad Strongwell personally for unlawful entry, unauthorized construction, environmental destruction, and trespassing. Gina added punitive damages and legal costs to the tune of $650,000.

By morning, Chad had filed a counter suit. his claim that the boundary between our properties was poorly defined, that his team had acted in good faith, and that I’d used intimidation tactics to obstruct a shared project of community value. Community value my ass. The judge called a preliminary hearing within 48 hours. County courthouse, third floor.

The courtroom was cold and smelled like printer ink and stale air conditioning. Chad walked in wearing a navy suit, two sizes too tight for his ego, flanked by three lawyers from some Austin firm with names like Branigan, Hol, and Carrington. He didn’t look at me as he sat. Gina opened with a quiet sledgehammer of a statement.

She laid out the evidence with military precision, satellite data, timestamped photos from my cameras, GPS logs from the bulldozer, all showing equipment sitting well over 70 yard inside my property line. Then she dropped the aerial drone footage, full HD, played right there on the court’s monitor. We watched together as a worker used a chainsaw to cut through my oak belt.

The sound was muted, but you didn’t need audio to hear the arrogance in every swing. Gina followed it with the county’s own GIS map, showing my deed boundaries, registered, notorized, and clear as a damn sunrise. One of Chad’s attorneys tried to argue implied easement based on what he called unclaimed terrain. Gina shut him down cold. No easement was ever recorded, applied for, or granted. This isn’t a paper error.

This is willful, unauthorized occupation of titled private land. The judge, a calm woman in her 60s named Miranda Owens, nodded slowly, tapping her pen. Then she turned to Chad. Mr. Strongwell, did you authorize construction on this site? I I green lit exploratory land use surveys, he stammered. Based on information my project manager, the judge raised a hand.

Did you verify who owned the land? Chad hesitated. I trusted my team. I see. She didn’t even need to raise her voice. The silence in the room made her judgment feel louder. That evening, we got the ruling. The court found Cedar Crest Ridge HOA guilty of unauthorized land use and ordered a complete stop to all development activity.

They were fined $650,000, damages for trespass, ecological disruption, removal of native flora, and legal costs. But that wasn’t all. The judge required them to restore the site, replanting trees, rehabilitating soil, and removing all infrastructure within 30 days. If not, fines would increase by 5,000 per day.

By the end of the week, Cedar Crest Ridge residents had caught wind of the disaster. Their HOA dues had been quietly used to fund an illegal luxury spa project without approval, without permits, and on stolen land. First came the whispers, then the homeowner meeting, then the storm. By Friday, eight lawsuits had been filed against their own HOA board. And Chad, well, he vanished for a bit.

But snakes don’t disappear. They coil. A few weeks passed. The lawsuits against Cedar Crest Ridge HOA multiplied like mosquitoes after a flood. Half their board had resigned. The spa project was dead. My oaks, or what was left of them, stood silent, skeletal reminders of Chad’s arrogance.

I figured he’d cut his losses and move on. I figured wrong. It started with a flicker on my dashboard, a red triangle on the security feed flashing under the words RFID anomaly, North Gate. The system had detected a false card swipe twice, then a third time, 12 minutes later. No access granted, but it was enough to put me on alert.

I checked the camera feed from the gate. Static. That gate was connected to a dedicated line, shielded and buried, not something that just goes offline. I sent Tyler out to check the wiring the next morning. The junction box had been tampered with, wires stripped clean, fingerprint smudges left behind like a middle finger.

We replaced the hardware and reinforced it with a steel cage. I didn’t file a report. Not yet. Maybe it was just some teenage vandal with a crowbar and a poor sense of humor. Then my cows started dying. Six head, dead within 48 hours. Not shot, not mauled, no visible wounds at all. Just collapsed near the south paddic. Stiff and silent.

Doc Hernandez ran tox screens. I’ll never forget the look on her face when she gave me the results. triazine compound, strong, agricultural grade, possibly siphoned from turf pesticides. It was poured directly into the water troughs. Deliberate, she said, not runoff. Someone did this on purpose. That was the moment I stopped thinking in terms of lawsuits. This wasn’t a business dispute anymore.

This was a warning. I filed a police report. Of course, deputies came, snapped photos, scribbled on clipboards, promised they’d look into it, but we all knew how that would go. Without footage, without a license plate, there’d be no arrests, just paperwork and maybe a shrug.

So, I did what I should have done the day I got back from Austin. I activated Phase Delta. Now, that’s not some Hollywood operation. It’s just what we jokingly call the full lockdown protocol. Thermal drones, passive IR trip wires, pressure plates, low light cams, the works. The kind of setup you’d use if you expected a coyote to come back smarter, or in this case, human.

Jason and Rick helped install the new perimeter. Grumbling but focused. We added motion activivated spotlights, GPS tags on the feed bins, and reenabled the ground sensors near the southern creek. Every alert fed back to a single encrypted tablet mounted in my kitchen wall. Then we waited. It didn’t take long.

Four nights later, the Southern Motion Grid pinged just after 2:00 a.m. Multiple contacts by pedal moving slow. Controlled gate, not wildlife. Tyler switched the feed to infrared. Three heat signatures, two large, one smaller. They were coming through the same breach where the construction road had been, now overgrown and barricaded.

One of them carried what looked like a heavy bag. We tracked them in silence. They moved with purpose. Not wandering, not drunk, not kids. They reached the camera tower. Then one of them pulled out a crowbar. The next 10 minutes were a blur. Tyler triggered the flood lights remotely, flooding the clearing in white. The men froze, caught mid-motion.

One of them looked directly into the lens. It was Chad Strongwell. He didn’t wear the tailored suit anymore, just a hoodie, boots, and a clenched jaw. The other two, we’d run their faces later through a local private security database, former contract guys. One had a charge for assault, the other for arson. I hit the emergency call button.

Sheriff Harper was on site in 9 minutes. When the squad car pulled up, the flood lights still bathing the clearing. I was standing there with my rifle slung and both hands in view. Chad didn’t run. He didn’t have time. Deputies cuffed all three on the spot. One of the bags contained bolt cutters, spray paint, and two bottles of sulfuric acid. Intent was clear.

destruction of property, evidence tampering, criminal trespass, and for Chad, retaliation after civil litigation. He just stood there in the light, face pale, lips pressed thin, not defiant anymore, just exposed. He looked at me once as they led him past. I didn’t smile. I didn’t speak. I just watched as the HOA president of Cedarrest Ridge got loaded into the back of a squad car like a common vandal because that’s what he was now.

They held Chad in county lockup for 48 hours before he posted bail. I expected him to slither off with his lawyer brigade, claim it was all a misunderstanding, maybe pin the blame on the two goons he brought along, but the evidence didn’t care about his excuses. The deputies had him dead to rights. Our cameras caught everything.

The break-in, the tools, the acid, even the quiet moment where he hesitated by the tower, like he finally realized the hole he dug for himself. Not that it mattered anymore. Gina and I met with the district attorney the following morning. The charges against Chad included criminal trespassing, felony sabotage, attempted destruction of evidence, and the kicker, agricultural animal poisoning, which under Texas law falls under federal livestock protection statutes. That last one hit hardest.

Killing cattle isn’t just vandalism. It’s a threat to food supply and economic livelihood. In Texas, we take that seriously. The DA was eager. Apparently, Chad had rubbed elbows with the wrong judge a few years back, tried to pressure him into reszoning county land. Let’s just say nobody was lining up to protect him this time.

Meanwhile, we expanded the suit on the civil side. Gina filed an additional claim for willful sabotage, attempted intimidation, and economic damages relating to livestock loss. We requested another $400,000. My insurance adjuster backed us. The evidence was too overwhelming to ignore. Cedar Crest Ridge HOA tried to distance themselves fast.

Their board held an emergency meeting and voted to suspend Chad pending legal resolution. But the damage was done. News had already broken. The Austin Ledger ran a headline that read, “HOA president arrested for cattle poisoning and armed trespass. Claims land wasn’t being used.” Hell of a legacy. At the arraignment hearing, Chad’s lawyer tried to get the charges dropped, citing mental distress, temporary lapse in judgment, and my favorite, excessive provocation by Mr. Miller. The judge didn’t flinch.

“Provocation?” she asked. “You’re telling this court that a man defending his own property provoked your client into chemical sabotage?” Even the stenographer cracked a smirk. No bail reduction. Trial date set. Chad didn’t look at me as they escorted him out.

But one of his former neighbors, a woman named Camille, whose garden club I’d never met, slipped me a handwritten note on her way past in the hallway. Thank you. We never knew how far he’d go. We were all scared to say anything. The tide had shifted. I wasn’t the angry rancher with a gun anymore. I was the guy who finally stood up. Cedar Crest Ridge. It was unraveling. HOA dues frozen. Civil claims pouring in.

Half a dozen residents filed suit for mismanagement of funds. Apparently, Chad had siphoned over $200,000 from the HOA account to privately fund the clubhouse without authorization, without disclosure. Turns out my ranch wasn’t the only place he trespassed. Meanwhile, I reinforced my fencing and brought in an environmental firm to start soil restoration where the spa site had been.

We planted new oaks, one for every cow he killed, and every day I woke up knowing the law, slow as it sometimes is, was finally catching up. The trial started on a Monday. The courthouse smelled like stress and burnt coffee. Reporters hovered outside like vultures in polyester suits, snapping photos every time a door creaked open. I showed up in jeans and a button-down, boots dusted but polished.

Gina told me to look credible but unshakable. I figured that meant look like yourself, but don’t punch anyone. Chad arrived in a charcoal suit that looked expensive and uncomfortable. His face had changed. Gone was the smug confidence. What replaced it wasn’t remorse, just panic hidden behind a legal haircut.

The prosecution opened with the footage. Again, same video, same timeline, the trespass, the sabotage attempt, the acid, the bolt cutters. The exact moment Chad looked into the thermal drone lens like a man who just realized he stepped into a bear trap. only this time it wasn’t just for a judge. It was for 12 jurors, nine of whom had land or livestock of their own.

The prosecutor, a wiry man named Collins, didn’t sugarcoat it. Ladies and gentlemen, this is not a zoning dispute. This is a pattern of deliberate lawbreaking committed by a man who thought money could erase boundaries. Gina and I sat two rows back behind the rail. when she leaned toward me and whispered, “He’s cooked.

” I didn’t argue. The parade of witnesses was relentless. The vet who confirmed the poisoning, a soil scientist who explained the ecological damage. A deputy who walked the jury through the arrest footage from three angles. Even a forensic tech who traced digital fingerprints to Chad’s private laptop where he’d kept a folder titled Cedar Ridge expansion offgrid plans.

His defense tried every card in the deck, claimed the footage was misleading, that he was only inspecting damage, that the chemicals weren’t his. But the evidence didn’t just suggest guilt. It painted it in oil and framed it. Then came the kicker, a surprise witness, one of the former HOA treasurers, a man named Allan Boyd, who’d quit quietly six months prior.

On the stand under oath, he testified that Chad had pressured him to reclassify HOA funds as development grants. That when Allan refused, Chad told him, quote, “If you won’t sign it, I’ll find someone who will. Nobody will care once the spa is built.” The courtroom didn’t gasp. It just froze, and the judge’s eyes narrowed like a hawk spotting prey. That day, the jury recessed early. Verdict came the next morning. Guilty on all counts.

Criminal trespass, destruction of agricultural property, sabotage, poisoning livestock, conspiracy to obstruct justice. Sentencing was swift. 12 years. first seven without parole. Chad stood silently while the judge listed every count like nails in a coffin. Then she added something extra. Mr. Strongwell, you didn’t just break the law.

You used your influence to convince others to help you break it. You betrayed their trust. You betrayed your own community. He was led out in cuffs. As for Cedar Crest Ridge HOA, well, that ship sank fast. The state froze their accounts. A court-appointed receiver began selling off common assets, the gym, the tennis courts, even the decorative stone fountain out front.

The land set aside for the spa was turned over to the county to cover the mounting judgments. The residents, most of them stunned, quietly turned on one another. Accusations flew, friendships dissolved. Camille, the woman who’d passed me that note, told me they were planning to dissolve the HOA entirely. Too toxic to salvage. Funny thing is, I didn’t feel triumphant. Not exactly, just resolved.

It was over. My land was mine again. The creek ran quiet. The trees, scarred as they were, still stood, and the man who tried to rewrite my boundaries was now living inside steel ones of his own. A month after the verdict, I stood at the edge of the southern clearing, watching a new sapling take root, where the spa foundation used to be.

The restoration crew had done good work. Native grasses were coming back, the soil tested clean, and the creek had stopped carrying that faint chemical tang. We’d reclaimed it inch by inch. The last of the surveillance equipment was boxed up that morning. Faze Delta retired. I left a few cameras near the gate, more out of habit than fear.

The land was quiet again, not empty, just at peace. I spent the afternoon writing. The article was something Gina encouraged. Landowner’s journal wants your story, Cody. Tell it your way. So, I did. I titled it. You can build a mansion on sand, but if you build on stolen land, you’re just digging a cell. By the time I finished, the shadows had stretched long across the paddics.

Rick was working on the hanger and Jason was messing with the ATV’s throttle. Life, as it does, had moved on. Then I saw the U-Haul, big, white, slow, lumbering up the old HOA road from what used to be Cedar Crest Ridge. A young couple was following it in a dusty Subaru. New neighbors, first ones since the dissolution. Curious folks, I figured.

The moving truck stopped near the old boundary. A man stepped out holding a wooden stake and a red metal sign. He walked five paces into the field and drove it into the ground. Private driveway. No trespassing. I walked over slow, hands in pockets. He glanced up, friendly enough, nervous. Hey, uh, I hope this is okay. GPS said the property line starts right here.

We just wanted to mark it before fencing goes in. I looked at the stake, then back at him. Paperwork all squared away. Yes, sir. Deed, plat, survey, triple checked. I smiled. Then you’re doing it right. His wife waved from the car. We heard stories, she said, about a guy with a rifle and a camera system that caught a billionaire trying to build a helipad on a cattle ranch. Sounds exaggerated, I said, but not by much.

We shook hands. I turned to leave. Hey, the man called out. You got any tips for firsttime land owners? I paused, thought about it. Yeah, I said. Never assume someone else’s silence means surrender. And never ever trust a man who calls himself a visionary before you’ve seen his property lines. They laughed. I didn’t. Some lessons cost blood. Some just need a damn good fence.