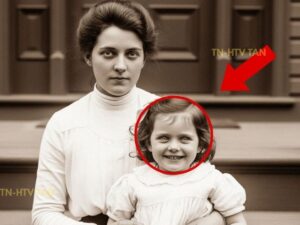

In November 2023, genealogologist Patricia Hawthorne was organizing family documents at her grandmother’s estate in Salem, Massachusetts when she discovered a photograph that would haunt her for months. The sepia toned image dated June 1906 showed a young woman in her 20s holding a little girl of perhaps 4 years old on the front steps of a Victorian house.

The mother, dressed in the high-colored fashion of the Edwwardian era, gazed directly at the camera with the serious expression, typical of formal portraits from that time. Her dark hair was pulled back in the Gibson girl style, and her clothing suggested a middle-class family with modest prosperity.

She held her daughter protectively, one hand resting on the child’s shoulder. But it was the little girl that made Patricia pause. While the mother’s expression was appropriately solemn for the formal photographic session, the child displayed a wide, unnaturally bright smile that seemed completely out of place.

Children in early 20th century portraits typically appeared serious or slightly uncomfortable due to the long exposure times required. Yet, this girl beamed with what appeared to be genuine joy. What disturbed Patricia most was the quality of the smile itself. It was too wide, too intense, and seemed to lack the natural spontaneity of genuine childhood happiness.

The girl’s eyes appeared unusually bright, almost glassy, and her pupils seemed dilated despite the bright outdoor lighting suggested by the shadows in the photograph. A handwritten note on the back of the photograph read, “Ellanor and little Margaret, June 1906, after Dr. Richardson’s treatment.” The notation troubled Patricia because she recognized the names from family stories.

Elellanar Morrison had been her great great grandmother and Margaret had been Elellaner’s daughter who had died tragically young. Family oral history had always maintained that Margaret had been a difficult child who had required special medical treatment for behavioral problems. The stories suggested that Margaret had been hyperactive and prone to violent outbursts until she received treatment from a local physician.

After the treatment, she had become calm and happy, but had died within a year from what the family described as a sudden illness. Patricia decided to research the photograph and the circumstances surrounding it. Unaware that her investigation would uncover a disturbing chapter in the history of early psychiatric treatment of children, Patricia contacted Dr.

Samuel Chen, a medical historian at Boston University who specialized in early 20th century psychiatric practices. When she showed him the photograph, Dr. Chen immediately recognized the signs of what would now be considered medical abuse disguised as treatment. “The early 1900s were a dark period for psychiatric medicine, particularly regarding children,” Dr.

Chen explained during their meeting at the university library. “Picians had very limited understanding of childhood behavioral disorders and often used treatments that were essentially chemical restraint. Dr. Chen provided historical context about psychiatric treatment in 1906. Children who displayed what would now be recognized as normal developmental behaviors, hyperactivity, defiance, or emotional outbursts were often labeled as morally insane or mentally defective.

Treatment typically involved harsh physical restraints, isolation, or experimental drug therapy. Dr. Richardson’s treatment mentioned in the photographs notation caught Dr. Chen’s attention. Research into Massachusetts medical records from the period revealed that Dr. Jeremiah Richardson had been a physician practicing in Salem who specialized in what he called behavioral modification therapy for troubled children. Dr.

Richardson’s methods documented in local medical journals from 1905 1907 involved the systematic administration of opium based medications to hyperactive children. He claimed that regular doses of opium derivatives could calm the savage nature of difficult children and make them more manageable for their families. The medical literature from the period shows that Dr.

Richardson’s treatments were considered controversial even by the standards of 1906. Several colleagues had expressed concern about his high dosages and the long-term effects on child patients. However, desperate parents often sought out his services when conventional discipline proved ineffective. Dr. Richardson’s own published case studies describe children who became angelically compliant after his treatments, displaying constant happiness and obedience that he characterized as evidence of successful therapy.

Modern medical knowledge reveals that these symptoms were actually signs of chronic drug intoxication. The bright, inappropriate smile visible in Margaret’s photograph was characteristic of opium intoxication in children. The dilated pupils, glassy expression, and unnaturally cheerful demeanor all suggested that the 4-year-old had been under the influence of opiates when the photograph was taken.

Patricia’s research into her family genealogy revealed troubling details about Margaret Morrison’s short life and the circumstances that led to her treatment by Dr. Richardson. Family documents painted a picture of a normal, energetic child whose behavior had been misinterpreted through the lens of early 1900s attitudes toward childhood.

Letters between Elellanar Morrison and her sister, preserved in the family collection, described Margaret as willful and defiant beyond normal childhood misbehavior. Eleanor wrote about her daughter’s refusal to sit still during church services, her tendency to run and play loudly in the house, and her occasional temper tantrums when denied something she wanted.

Margaret seems possessed by some restless spirit. Eleanor had written to her sister in 1905. She cannot sit quietly for even a few minutes and her energy exhausts me completely. Other mothers tell me their children are not nearly so difficult to manage. I fear there is something wrong with her mind. These descriptions, when viewed through modern understanding of child development, portrayed a completely normal 4-year-old girl displaying typical childhood energy and independence.

However, the rigid social expectations of 1906, particularly for girls, demanded absolute obedience and quiet behavior that many healthy children could not achieve. Eleanor’s letters revealed the social pressure she faced as Margaret’s mother. The other ladies at church have begun to stare when Margaret fidgets during services, she wrote. Mrs.

Whitmore suggested that perhaps Margaret needed firmer discipline, but even the strictest punishment seemed to have no lasting effect on her behavior. The correspondence showed Elellanar’s growing desperation as she tried various methods to control Margaret’s natural childhood exuberance. She consulted the local minister, tried different forms of discipline, and even considered sending Margaret to a boarding school for difficult children.

It was Margaret’s kindergarten teacher who first suggested that the child might benefit from medical treatment. The teacher reported that Margaret had difficulty sitting still during lessons, often spoke out of turn, and showed more interest in playing than in the structured activities expected of students.

By early 1906, Ellaner had become convinced that Margaret’s behavior indicated a medical condition requiring professional treatment. When she learned about Dr. Richardson’s reputation for helping troubled children. She saw it as the solution to her family’s problems. Investigation into Dr. Richardson’s medical practice revealed a systematic approach to treating children that would be considered criminal by modern standards.

His patient records discovered in the Salem Historical Society archives documented his treatment philosophy and methods in disturbing detail. Dr. Richardson believed that childhood behavioral problems were symptoms of nervous system hyperexitability that could be controlled through regular administration of what he called calming medications.

His treatment protocol involved daily doses of ldinum, a tincture of opium that was legally available and commonly used in medicine during the u early 1900s. The hyperactive child suffers from an overabundance of nervous energy that must be systematically reduced to achieve normal behavior. Dr. Richardson wrote in his 1906 medical journal through careful administration of opiate preparations.

The child’s excessive vitality can be channeled into appropriate dosility and happiness. Dr. Richardson’s records showed that he treated over 150 children between 1904 and 1907 with parents paying substantial fees for what they believed was advanced medical care. His success was measured by the dramatic behavioral changes in his young patients who transformed from active, sometimes defiant children into quiet, perpetually smiling, compliant individuals.

The treatment protocol for Margaret Morrison documented in Dr. Richardson’s files began in March 1906 with a daily dose of one teaspoon of ldinum administered in sweetened water. Eleanor was instructed to give Margaret the medication each morning and evening with additional doses if the child showed signs of excessive energy or defiance.

Within 2 weeks of beginning treatment, Eleanor reported dramatic changes in Margaret’s behavior. “Margaret has become the most delightful child,” she wrote to Dr. Richardson. She sits quietly during church services, obeys my instructions without argument, and maintains a cheerful disposition throughout the day.

Your treatment has worked a miracle. However, Dr. Richardson’s private notes revealed his awareness that the children’s improved behavior came at a significant cost. Many of his patients displayed symptoms that modern medicine would recognize as chronic drug intoxication. dilated pupils, slowed reflexes, periods of stuper alternating with artificial euphoria, and increased susceptibility to illness. The mortality rate among Dr.

Richardson’s patients was significantly higher than the general child population, though deaths were typically attributed to common childhood illnesses rather than drug toxicity. Eleanor Morrison’s letters to family members during the summer of 1906 documented Margaret’s gradual physical and mental deterioration under Dr.

Richardson’s treatment. Though Eleanor interpreted these changes as positive developments in her daughter’s behavior, Margaret has become so well- behaved and happy since beginning Dr. Richardson’s treatment. Eleanor wrote to her sister in July 1906. She smiles constantly and never argues or causes disruption.

However, I have noticed that she seems less interested in her toys and spends much of the day sitting quietly, which I suppose indicates her growing maturity. The behavioral changes Elellanor described actually represented signs of chronic opiate intoxication. Margaret’s loss of interest in play, her constant inappropriate happiness, and her unusual compliance were symptoms of drug-induced personality changes rather than normal development or successful treatment.

Other family members began to express concern about Margaret’s condition during family visits. Eleanor’s mother wrote from Boston. Little Margaret seems different from when I saw her last Christmas. She smiles and agrees to everything, but there’s something vacant in her expression. She doesn’t seem to really see or hear us when we speak to her. Dr.

Richardson’s treatment records show that he gradually increased Margaret’s ludinum dosage throughout the summer of 1906, responding to what he interpreted as tolerance development. By August, Margaret was receiving nearly three times the initial dose, an amount that would be considered dangerous even by the medical standards of the time. Elellanar’s letters from late summer revealed physical changes that alarmed even her.

Margaret has become very thin despite eating her meals, and she often seems confused about simple things. She fell down the stairs yesterday because she seemed not to notice the steps. Dr. Richardson assures me this is normal as her nervous system adjusts to the treatment. The photograph taken in June 1906 captured Margaret at the height of her opiate intoxication when the drug’s euphoric effects created her disturbing, inappropriate smile.

The image documented a child whose natural personality had been chemically suppressed in favor of artificial compliance and happiness. By September 1906, Margaret’s condition had deteriorated to the point where even Eleanor began questioning the treatment. However, Dr. Richardson convinced her that stopping the medication would cause Margaret’s behavioral problems to return even worse than before, creating a dependency that trapped the family in continued treatment.

Margaret’s tragic fate was sealed by the medical ignorance of the era and her mother’s desperate desire for a well- behaved child. Investigation into Salem’s historical records revealed that Margaret Morrison was not Dr. Richardson’s only victim and that the local community had become increasingly concerned about the physicians methods and their effects on child patients throughout 1906.

The Salem Evening News Archives contained several articles from the period discussing what the newspaper diplomatically called concerns about modern medical treatments for children. While not naming Dr. Richardson specifically, the articles referenced reports of children who had become unnaturally docil after receiving medical treatment for behavioral problems.

Local school records showed a pattern of children withdrawing from classes after beginning treatment with Dr. Richardson teachers reported that formerly active students became lethargic, unresponsive, and unable to participate in normal classroom activities. However, parents generally interpreted these changes as improvements in their children’s behavior. Mrs.

Katherine Walsh, a school teacher at Salem Elementary, kept personal diary entries that documented her concerns about Dr. Richardson’s patients. Several of my former students have become like little ghosts of themselves,” she wrote in September 1906. “They sit quietly and smile when spoken to, but there’s no spark of intelligence or curiosity left in their eyes.

” The local minister, Reverend Thomas Blackwell, had also begun expressing private concerns about Dr. Richardson’s treatments. Church records showed that several families had requested prayers for children who had become strangely quiet after medical treatment. Though the families presented these requests as thanksgiving for their children’s improved behavior, Dr.

Richardson maintained his respectability in the community through careful management of his reputation and the desperate gratitude of parents whose difficult children had become manageable. He regularly published articles in local newspapers about the importance of medical treatment for childhood behavioral disorders.

However, other physicians in Salem were beginning to question his methods. Dr. Marcus Webb, who practiced general medicine in the area, wrote to the Massachusetts Medical Board in October 1906, expressing concern about the unusual number of childhood deaths among families who had consulted Dr. Richardson. Dr.

Webb’s letter described his observations. I have been called to attend several children who were patients of Dr. Richardson, and I have noted symptoms consistent with chronic poisoning. The children display signs of narcotic intoxication, including dilated pupils, slowed reflexes, and periods of stuper. I fear that Dr.

Richardson’s treatments may be causing more harm than the original behavioral problems they purport to address. The medical board’s response was minimal, reflecting the limited oversight of medical practice in 1906. They sent a letter to Dr. Richardson requesting information about his treatment methods, but took no action to investigate or restrict his practice.

Eleanor Morrison’s final letters about Margaret, written in late 1906 and early 1907, documented the tragic end of Dr. Richardson’s treatment and the child’s death from what would now be recognized as drug toxicity and related complications. In the November 1906, Eleanor wrote to her sister with growing alarm.

Margaret has developed a persistent cough and seems to have difficulty breathing at times. Dr. Richardson says this is a common cold, but she has been ill for nearly 3 weeks without improvement. She still smiles and obeys, but she seems to lack the energy even for simple activities. Margaret’s respiratory problems were likely related to the depressant effects of chronic opiate use, which can suppress the breathing reflex and make patients more susceptible to respiratory infections.

However, Eleanor continued administering the ldinum on Dr. Richardson’s orders, believing it was necessary for maintaining Margaret’s good behavior. Dr. Richardson’s notes from this period show his awareness that Margaret was experiencing serious medical complications, but he attributed them to constitutional weakness.

rather than drug toxicity. He actually increased her lodinum dosage, claiming it would help her rest and recover from her illness. By December 1906, Margaret’s condition had deteriorated severely. Eleanor’s letters described a child who spent most of her time sleeping or sitting motionless, who had difficulty eating, and who seemed unaware of her surroundings.

Yet Elellanar continued to describe Margaret as peaceful and well- behaved, unable to recognize the signs of serious medical crisis. “Margaret hardly speaks anymore, but she still smiles when I look at her,” Elellanar wrote in what would be her final letter about her daughter. “Dr. Richardson assures me that this quietness indicates her complete recovery from the nervous condition.

She requires so little attention now, sitting contentedly for hours without disruption.” Margaret Morrison died on January 15th, 1907 at the age of 5. The death certificate listed cause of death as pneumonia and respiratory failure, making no mention of the chronic drug treatment that had likely contributed to her death by suppressing her immune system and breathing reflexes.

Elellanar never questioned whether Dr. Richardson’s treatment had contributed to Margaret’s death. She continued to believe that the medication had successfully cured her daughter’s behavioral problems and that Margaret had died from an unrelated illness. The guilt Ellaner carried was for her earlier impatience with Margaret’s natural childhood energy, not for subjecting her to harmful medical treatment. Dr.

Richardson attended Margaret’s funeral and offered Elellanar his condolences, expressing satisfaction that Margaret had lived her final months as a well- behaved and happy child, thanks to his successful treatment. Patricia Hawthorne’s research into her family history, had uncovered Margaret’s tragic story.

But further investigation revealed that dozens of other children in Salem had suffered similar fates under Dr. Richardson’s care between 1904 and 1907. Death records from Salem during this period showed an unusual pattern of childhood mortality among families who had consulted Dr. Richardson. Children who had been healthy prior to his treatment developed respiratory problems, digestive issues, and other complications that modern medicine would associate with chronic drug toxicity.

The Salem Historical Society’s archives contained records of at least 12 child deaths that occurred within 18 months of beginning treatment with Dr. Richardson. All had been attributed to common childhood illnesses, pneumonia, influenza, digestive disorders, but the pattern suggested a systematic problem with his treatment methods.

Patricia contacted Dr. Rachel Torres, a pediatric toxicologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, who reviewed the historical evidence and confirmed that the symptoms described in family letters were consistent with chronic opiate poisoning in children. Dr. Richardson was essentially conducting a systematic poisoning of children under the guise of medical treatment. Dr.

Torres concluded the doses of Ldinum he was prescribing would have been toxic for children and chronic administration would have caused the exact symptoms these families described. The investigation revealed that Dr. Richardson’s practice had ended abruptly in early 1907, shortly after Margaret’s death and the deaths of two other child patients within the same month.

He had left Salem without explanation and disappeared from Massachusetts Medical Records. Research into medical licenses from other states eventually located Dr. Richardson in Philadelphia, where he had established a new practice under slightly different credentials. Pennsylvania medical records showed a similar pattern of child patients with behavioral problems who received opiate treatments and experienced high mortality rates. Dr.

Richardson’s practice in Philadelphia ended in 1909 following complaints from local physicians and several suspicious child deaths. He moved again to Baltimore, then to Richmond, continuously relocating whenever medical authorities began investigating his methods. The pattern revealed a physician who systematically exploited parental desperation and medical ignorance to conduct what amounted to experimental drug treatment on children.

His victims were typically children whose only disorder was normal childhood energy and independence that conflicted with social expectations of the era. By the time authorities began seriously investigating his methods, Dr. Richardson had treated hundreds of children across multiple states, leaving a trail of death and damaged families who never understood that their children had been victims of medical abuse rather than beneficiaries of advanced treatment.

Patricia’s investigation revealed that medical authorities and community leaders had been aware of problems with Dr. Richardson’s treatments, but had failed to take action to protect children or hold him accountable for the harm he caused. The Massachusetts U Medical Board’s archives contained multiple complaints about Dr.

Richardson’s methods and patient outcomes, but the board had consistently dismissed concerns or conducted only superficial investigations. Board meeting minutes from 1906 1907 showed more concern about protecting the medical profession’s reputation than investigating potential malpractice. While Dr.

Richardson’s methods may be unconventional, wrote board president Dr. Samuel Whitney in 1907. We must be cautious about restricting innovative approaches to difficult medical problems. The high mortality rate among his patients likely reflects the severity of their conditions rather than inadequacy of treatment. This administrative response reflected the medical establishment’s reluctance to acknowledge systematic problems within the profession even when evidence clearly indicated patient harm.

Protecting professional reputation took precedence over patient safety and accountability. Local newspapers had also contributed to the cover up by refusing to publish critical coverage of Dr. Richardson’s practice. The Salem Evening News had received information about child deaths and family concerns, but chose not to investigate or report on the pattern, likely due to pressure from prominent families who had used Dr.

Richardson’s services. Many of Dr. Richardson’s clients had been wealthy or socially prominent families who preferred to keep their children’s behavioral problems and medical treatments private. These families use their influence to prevent public scrutiny of Dr. Richardson’s methods, inadvertently enabling continued abuse of other children.

The conspiracy of silence around Dr. Richardson’s practice was maintained through a combination of professional protection, social embarrassment, and genuine ignorance about the harmful effects of his treatments. Parents who had lost children continued to believe that their children had died from natural causes rather than medical malpractice.

The lack of accountability for Dr. Richardson’s crimes allowed him to continue practicing in other locations where he repeated the same pattern of abuse with new victims. His mobility between states and the limited communication between medical boards made it possible for him to avoid consequences for his actions.

The systematic failure to investigate and prosecute Dr. Richardson represented broader problems in early 20th century medical oversight that enabled other forms of patient abuse. Without meaningful accountability mechanisms, dangerous physicians could continue practicing and harming patients across multiple jurisdictions.

Only the gradual development of professional standards, medical licensing oversight, and patient advocacy would eventually make such systematic abuse more difficult to perpetrate and conceal. Patricia Hawthorne’s investigation into her family’s tragic history resulted in formal recognition of the children who had been victims of Dr.

Richardson’s medical abuse and acknowledgment of the systematic failures that had enabled his crimes. The Massachusetts Medical Society issued a formal statement acknowledging that Dr. Richardson had conducted systematic medical abuse of child patients under the guise of legitimate treatment. The society apologized to descendant families and established a memorial fund for research into historical medical ethics violations.

Patricia worked with local historians and medical ethicists to document the full scope of Dr. Richardson’s abuse and its impact on families in Salem and other communities where he practiced. Their research identified over 200 child victims across multiple states between 1904 and 1915. When Dr. Richardson’s career finally ended.

The Salem Historical Society created an exhibit about the case, using it as an educational tool to discuss the importance of medical oversight, informed consent, and protection of vulnerable patients. Margaret Morrison’s photograph became a centerpiece of the exhibit, illustrating how medical abuse could be disguised as successful treatment.

Medical schools began incorporating the Dr. Richardson case into their ethics curricula as an example of how social expectations and parental desperation could be exploited by unscrupulous practitioners. The case demonstrated the importance of evidence-based medicine and peer review in preventing harmful treatments. Descendant families of Dr.

Richardson’s victims finally received answers about their relatives deaths and understanding of the historical context that had led to these tragedies. While justice was no longer possible, acknowledgement of the truth provided closure and validation of family concerns that had been ignored for over a century.

Patricia established a research foundation dedicated to investigating historical cases of medical child abuse and supporting families affected by such tragedies. The foundation’s work helped identify other cases of systematic patient abuse that had been hidden by institutional coverups and social silence. The investigation into Margaret Morrison’s death revealed the importance of questioning medical authority, protecting vulnerable patients from exploitation, and maintaining rigorous oversight of medical practice.

Margaret’s disturbing smile in the 1906 photograph had finally led to recognition of her suffering and prevention of similar tragedies. Dr. Richardson’s victims were memorialized as examples of children who deserved protection from medical exploitation and whose deaths contributed to the development of modern patient safety standards.

Their stories served as a reminder that medical authority must always be balanced with accountability and genuine concern for patient welfare. Margaret Morrison and the other children who died under Dr. Richardson’s care had finally received the recognition and justice that had been denied to them for over a century, ensuring that their tragic stories would serve to protect future generations of vulnerable patients.