German POWs Couldn’t Believe Their Eyes when they Met American Cowboys

July 12th, 1943. The train screeched as its iron wheels ground against the hot rails, sparks flashing in the noon light. Dust swirled up from the Texas prairie, sticking to the sweat of the soldiers crammed inside the box. They had been told they were bound for humiliation, for punishment, perhaps even for starvation.

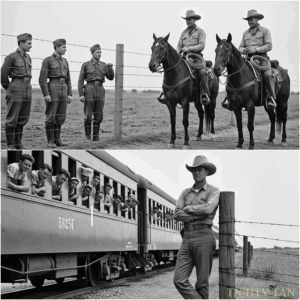

Some whispered that America would treat them like cattle, beasts unworthy of dignity. Yet, as the brakes hissed and the cars jolted to a stop, what first filled their vision was not the cold geometry of concrete walls, nor the looming towers of machine gun nests, but a man. He leaned against a fence post, one boot hooked casually on the rail, a broad stson shading his eyes, a glint of metal spurs catching the merciless sun.

The German prisoners pressed against the barred windows, squinting through grime and disbelief. One muttered a word that hung between awe and mockery. Cowboy. He had seen them before, but only in American films smuggled into Germany before the war. For most of these men, Hollywood was a land of fantasies, a world as unreal as fairy tales.

Yet here he stood in flesh and dust, framed by an endless sky that seemed to mock their confinement. As the train doors clanged open, the air spilled in, thick with the smell of sage brush, cattle, and manure. It was not the stench of war, but the odor of life itself, stubborn and unbroken.

The prisoners stumbled out, blinking against the light, shackled not by chains, but by exhaustion. Their boots sank into the loose soil, so different from the cobblestones of Bremen, Hamburg, or Berlin. They expected jeers, rifles thrust at their ribs, snarling commands. Instead, the guards, most of them farmers drafted into duty, simply watched with a quiet patience.

And there, among them, stood more men in wide-brimmed hats and leather boots. Americans who looked less like soldiers of an industrial empire and more like characters pulled from dime novels. One pal later recalled in his diary, “I thought we had been transported into a moving picture. There were horses grazing beyond the fence, and the men who guarded us carried themselves not as tormentors, but as ranchers, watching their herd.

Only we were the herd now.” The irony was sharp. These were men who had fought in Raml’s Africa Corps, who had stood in the sands of Tunisia, who had believed in the myth of German superiority. Yet here, stripped of their rifles and pride, they were confronted by Americans whose weapons were not merely carbines, but a way of life. Relaxed, confident, born of wide open spaces.

To the Germans, accustomed to rigid hierarchy and shouted orders, the cowbo loose stance and easy silence carried a different kind of authority. A sergeant barked for them to form ranks, but even as they obeyed, many could not stop staring at the horizon. There were no looming walls, no endless barbed wire stretching into infinity, just the prairie, the ripple of grass under the wind, and the faint shadow of cattle moving in the distance. They felt a strange unease.

This was captivity, yes, but it was also a freedom unfamiliar to men who had lived under the iron discipline of the Reich. As they were marched toward the camp, they saw the barbed wire fence. Simple, almost fragile compared to what they expected. The wooden towers stood, but unmanned for the moment, their ladders empty. Guards strolled rather than marched.

Some even tipped their hats to the locals who had gathered to watch. Children perched on fence rails, curious to see the so-called enemy. Women in sun bonnets found themselves in the heat, whispering at the sight of young German men no older than their own sons overseas. It was a tableau of contradictions. Enemies met with the gaze of neighbors, conquerors transformed into spectacles.

Inside the camp sprawled more like a ranch than a prison. Long wooden barracks lined in neat rows, a mess hall at the center, and wide fields beyond where the prisoners would soon work. The first shock came when the smell of food wafted toward them, beef stew simmering, the bitter aroma of coffee brewing. For many, this was a cruelty in itself. They had been told America would starve them.

Instead, the scent of abundance filled the air. One soldier whispered bitterly, “My mother has not tasted beef in 3 years.” The cowboy, who had first caught their eyes, still leaned near the fence, as if amused by their disbelief. He chewed on a blade of grass, spat into the dirt, and nodded slightly as the column passed.

That simple gesture struck deeper than a shouted insult. It was not triumphalism, but indifference, the mark of a man secure in his place, unthreatened by their former power. The Germans were herded into their barracks. But even inside, conversation buzzed about what they had seen.

Some insisted it was a trick, propaganda designed to soften them before true cruelty arrived. Others whispered of opportunity, work, food, perhaps even dignity. One young officer, barely 22, sat on his bunk and muttered, “If this is captivity, it is different than any captivity I imagined.” Outside, the sounds of ranch life drifted through the camp. A dog barking, a horse nighing, the loing of cattle.

The prisoners lay on their bunks, listening, torn between relief and shame. They had marched into battle to expand a Reich. Yet here they were, fed and guarded by men who seemed more myth than military. The cowboy was no invention. He was flesh, dust, and leather, and he lived freer on the edge of a fence than they had ever been in the armies of Europe.

Night fell with a desert swiftness. The horizon glowed with the last embers of sunlight, and the prisoners watched through the cracks in their barracks walls. The same cowboy stood by a lantern now, its glow tracing the line of his hat.

A harmonica drifted from somewhere beyond, playing a tune the Germans did not know, but felt in their bones. For the first time since capture, silence was not filled with despair, but with annoying confusion. The day had begun with certainty. Captivity meant degradation. Yet by its end uncertainty reigned. Was this land of cattle, coffee, and cowboys truly their prison? Or was it in some mocking twist of fate a glimpse of a freedom they had never known at home? And as one prisoner scribbled in his diary that night by the dim light of a contraband candle, he left words that would echo long after the war. I fear less the

barbed wire than the horizon beyond it. For the first time, I wonder if we are the ones who have been fenced in all along. The first morning began with a whistle, sharp, piercing, it cut through the soft hum of the prairie and jolted the Germans awake.

They rose stiffly from their bunks, expecting rations of watery soup or hard bread, the kind of punishment rations whispered about on the voyage. Yet when they shuffled into the mess hall, the scene startled them. Long wooden tables were lined with steaming bowls of beef stew, slices of cornbread stacked on tin trays, and pictures of hot black coffee that filled the room with its bitter perfume.

It was not luxury, not by American standards, but to men who had marched on empty stomachs through North Africa or survived on airats bread in Europe, it was excess. Some hesitated, unsure if it was a trap. A guard, his hat tipped back, urged them forward with a simple gesture. “Eat,” he said, as if it required no explanation.

One prisoner lifted his spoon, sipped the broth, and closed his eyes. The beef melted on his tongue. Another bit into the cornbread, and laughed quietly. It was sweet, softer than any bread he had known at home. He whispered, almost ashamed, “My family has not seen white flour in years.” The others nodded, chewing in silence.

Every mouthful a reminder that their loved ones back in Germany were enduring hunger while they, the captured, ate like men on holiday. Words spread quickly. Letters home, carefully censored but still full of clues, hinted at the abundance. A camp report from 1944 recorded one prisoner writing, “Mother, do not worry for me. I eat here more meat than I did as a boy.

” Another noted the endless coffee, a drink reserved in Germany for the wealthy, now poured in chipped mugs without ration tickets. Some guards chuckled at the prisoner’s astonishment, muttering that the menu wasn’t even special. It was what any American farmand might eat on an ordinary day.

The barbed wire loomed outside, but inside the camp, the rhythms of ranch life began to seep in. After breakfast, prisoners were marched out not to punishment drills, but to work details, harvesting cotton, repairing fences, tending fields, or unloading hay bales on local ranches. Under the Geneva Convention, they could be assigned non-military labor.

And in the agricultural states, their presence was desperately needed. With American men overseas, the farms lacked hands. Now the enemy carried buckets of water, hauled grain sacks, and guided plows behind horses. At first there was grumbling. Many PS thought farm labor beneath their status as soldiers.

Some tried to resist, hoping for conflict that would prove the cruelty of their captives. Yet the guards rarely raised their voices. They pointed, demonstrated, sometimes even joined in. One cowboy, sweat dripping from beneath his hat, showed a young German how to lift a hay bale without breaking his back. The prisoner, embarrassed, imitated him.

Later, in the barracks, he admitted he had never before seen a man of authority help rather than order. Pay was another shock. Each man received credits, about 80 cents a day, for his labor. They could spend it in the camp canteen on toiletries, stationery, even small luxuries like chocolate or cigarette.

For men who had been indoctrinated to believe they would be starved, this simple transaction felt surreal. A German corporal once joked bitterly, “I fought for Hitler and earned nothing. I pick cotton for a cowboy and I am paid.” The cultural exchanges multiplied. On Sundays, local farmers who had hired PS sometimes offered them lemonade, biscuits, even a chair on the porch.

One elderly Texan recalled decades later that a young German helped him fix a fence, then sat quietly on the steps, staring at the open land. When asked what he was thinking, the prisoner said, “I never saw a country so big it does not end.” His voice carried awe, not resentment, but the abundance brought a new kind of conflict. Within the barracks, some men grew uneasy. They feared they were growing soft, seduced by food and fairness, losing their loyalty to the Reich.

Others whispered that the Americans had no right to treat them so well that it was a humiliation worse than beatings. A few clung stubbornly to Nazi ideology, sneering at their fellow prisoners who laughed during work or savored American meals. Tension brewed, dividing men between those who clung to old pride and those who began to question what strength truly meant.

In official reports, American officers noted these divisions. Some camps even segregated hardliners, fearing they would intimidate the others. But in everyday life, the lines blurred. A man could march into captivity, declaring himself superior, and a week later be humming cowboy songs he had heard from guards, tapping his foot as he washed down cornbread with another mug of coffee.

The sensory details etched themselves into memory, the creek of saddle leather as guards rode along the fences, the hiss of cornbread batter on hot skillet, the smell of cut hay drifting through open barracks windows. These things belonged not to prisoners, but to free men. Yet here the Germans lived among them, experiencing America not as conquerors or tourists, but as unwilling guests, who nonetheless found themselves changed. One prisoner later confessed in a memoir.

We feared beatings, but none came. Instead, they gave us bread so white it shamed us. They poured coffee until we were sick of it. They paid us to work their land. In their generosity, I found not comfort but confusion. His words captured the heart of the conflict.

How could an enemy show kindness when his own leaders demanded cruelty? Yet even in this paradox, humor seeped through. A Texas guard recalled teaching a German lieutenant how to rope a calf during downtime. The officer tried, missed, tried again, and ended up tangled in his own lasso while the Americans roared with laughter.

The guard later quipped, “That was the only German officer I saw surrender twice in one day.” For the prisoners, laughter became both shame and release, a recognition that the world they had been taught to despise was not only stronger, but freer in spirit. By autumn, the camp’s rhythms felt routine. Work, meals, letters, home, the occasional baseball game watched through fences. But beneath the surface, the shock of abundance still nod.

They ate beef while their families survived on potatoes. They drank endless coffee while mothers and wives stood in ration lines. Each spoonful was both gifted and wound. One evening, after a long day hauling hay, a group of Germans lingered by the fence as the sun sank over the plains. Beyond the wire, a cowboy lit a lantern, the glow illuminating his weathered face.

He tipped his hat and walked away, leaving only the sound of crickets and the distant loing of cattle. One prisoner whispered, “He works harder than we do. Yet he is free. Why do they treat us better than our own leaders?” The question hung heavy in the warm night air. The men returned to their barracks, silent, unsettled. They were full of bread and beef, yet empty of answers.

And as the lights went out, more than one wondered whether the true captivity lay inside the fence, or within the chains of belief they had carried from home. The days lengthened, not with monotony, but with strange discoveries. Within the barbed wire, life began to take on rhythms that felt almost civilized, unnervingly so. The Germans had expected to lose themselves in punishment, yet they found opportunities they had not known in their own homeland.

The barracks that smelled of hay and soap soon echoed with the scratch of pencils, the shuffle of books, the murmur of lessons. America, it turned out, was willing to teach its captives. Classes sprang up in the dusty camp halls. English lessons led by school teachers, woodworking taught by farmers who doubled as guards, even lectures in mathematics and history delivered by the prisoners themselves. Some men hunched over desks, sounding out halting English phrases.

Others hammered together crude chairs or carved small figures from pine, the scent of shavings clinging to their clothes. At night, the barracks glowed faintly with lantern light as men copied vocabulary words into notebooks, whispering, “Hello, coffee, cowboy,” trying the syllables on their tongues.

It was a freedom they had not expected. Inside the fence, their world widened. One prisoner later wrote, “I learned more in one year of captivity than in all the years of Hitler’s speeches. The irony was sharp. Behind barbed wire, under the eye of supposed enemies, they found space to think. Music bled through the nights as well.

Germans who had carried harmonas tucked in their kit began to play first sad folk tunes of their homeland, then daringly American cowboy songs they had overheard. Soon makeshift camp bands formed. Violins strummed, accordians wheezed, and the rhythms of ranch life wo themselves into the melodies of the defeated. Guards sometimes paused to listen, tipping their hats in quiet acknowledgement before walking on.

For the prisoners, it was unsettling how easily they could mimic the sound of a culture they had been taught to despise. The contradictions deepened with every passing week. Newspapers appeared, printed on mimograph machines, filled with essays, jokes, even editorials. Some issues carried debates over politics. Others offered poetry written in cramped German script.

By 1945, more than 400 camp newspapers circulated across the United States, each one a voice of men who, even as captives, refused silence. In one camp, an editorial asked openly, “Why do we speak of superiority when the cowboy feeds us and we cannot feed ourselves?” Such words might have been treasonous back home.

Here they were scribbled in ink and pinned to bulletin board. Beyond the wire, work continued. Prisoners cut wheat under the wide Nebraska sky, plucked cotton in Oklahoma heat, and branded cattle under the watchful gaze of ranchers who offered them water when the sun grew too cruel.

The smell of scorched leather, the hiss of branding irons, the dust in their mouths. It all became part of their days. Some grew proud of their labor, holding up callous hands as proof that they were not merely prisoners, but men still capable of usefulness. One guard recalled a moment that etched itself into memory. A German soldier, young and thin, wiped sweat from his brow after stacking bales of hay.

The rancher whose land he worked extended a hand and said simply, “Good job.” The prisoner froze. In Germany, no farmer would thank a soldier. Authority demanded obedience, not gratitude. Yet here was a cowboy, dusty and sunburned, treating him as an equal in labor. The young man shook the hand awkwardly at first, then with a firm grip.

Later that night, he confessed to a bunkmate that the handshake had shaken him more deeply than defeat on the battlefield. But not all embraced this new rhythm. Some hardened themselves, sneering at the softness of comrades who smiled at guards or studied English words.

They called them traitors, men seduced by the enemy’s comfort. Tensions simmerred. In certain camps, die-hard loyalists tried to control the barracks, bullying others into silence, reminding them of their oath to Hitler. American officials noticed. Reports described the need to separate hardcore Nazis from those who merely wanted to survive.

The barbed wire contained not just prisoners, but their conflicts, old allegiances battling new impressions. Still, the cowboy presence loomed large, an unspoken reminder of another way to live. The prisoners watched their guards play cards under lantern light, laugh freely, spit tobacco into the dirt, ride horses with casual mastery. Authority here was not barked in commands, but carried in the tilt of a hat, the slow draw of a word.

To the Germans, raised in the shadow of rigid order, this was baffling. How could discipline exist without terror? How could men command respect without raising their voices? One night, a prisoner recorded a moment in his diary. He had been walking near the fence after work, watching a cowboy lead his horse into the stable.

The guard hummed as he worked, pausing to stroke the animals neck, speaking softly to it. The German wrote, “I saw more kindness in his hand on that horse than I saw in a thousand salutes to my officers. It was a revelation, authority born not of fear, but of care.” Humor, too bridged the gap.

In one camp, prisoners played soccer inside the fence while guards cheered from the outside. A ball sailed too far and a cowboy kicked it back with surprising skill. The Germans laughed, shouting mock applause. The guard tipped his hat, grinning. It was absurd. Enemies sharing a game. The barbed wire the only barrier between them. Yet in that absurdity lay a truth the Germans could not ignore.

Humanity seeped through even the harshest boundaries. And so the conflict sharpened. Was this kindness a mask or was it genuine? Could men raised to believe in brutality accept dignity from those they called enemies? Every meal, every handshake, every note of music pressed the question deeper. Some answered with defiance, clinging to old pride.

Others silently began to wonder if they had been wrong all along. The camp’s routines might have seemed ordinary to outsiders. Work, meals, rest. Yet for the prisoners, each day chipped away at certainties. Barbed wire kept them enclosed, but inside that fence ideas moved freely. They debated, they studied, they played, and slowly a different vision of freedom crept into their bones.

As winter settled over the plains, the nights grew long and cold. The prisoners huddled in their bunks, blankets pulled tight, breath clouding in the frigid air. Outside the lanterns burned, and the cowboys paced slowly, their spurs clicking softly on frozen ground. Through the thin walls, the Germans could hear the faint strains of a harmonica, a lonely tune drifting across the camp.

Some closed their eyes and let it carry them. Others lay awake, unsettled, realizing that captivity had given them a taste of something more dangerous than cruelty, an idea of freedom that could not be unlearned. And in the silence before sleep, one whispered question passed from bunk to bunk, a question no one dared answer aloud.

If this is how America treats its prisoners, then how much freer must its people be? The war ended not with a roar in the camps, but with a whisper. Rumors moved through the barracks in the spring of 1945. Germany had surrendered. The Reich had fallen. Hitler was dead. The men sat stunned on their bunks, staring at their boots, their hands, the floorboards beneath them. Some wept quietly.

Others clenched their fists, unable to imagine a world without the regime that had defined their life. But outside the wire, the cowboys moved as they always had, feeding cattle, sipping coffee, adjusting saddles before dawn. For the prisoners, the collapse of their homeland contrasted painfully with the steady rhythm of the ranch life surrounding them. The Reich had promised permanence and delivered ruin.

The cowboy never promised anything, yet he endured. Repatriation began slowly. Trains lined up once more, ready to carry the defeated back across the Atlantic. Many prisoners felt relief at the prospect of going home. But there was also a knowing sorrow, an unease they could not name. They had entered America with certainty, that it was cruel, that it was decadent, that it was inferior to the strength of the Reich.

They now left with their arms full of contradictions, their stomachs full of cornbread, their ears full of cowboy songs, and their hearts carrying memories of a freedom they had never known before the war. Letters preserved from those final weeks reveal the dissonance. One soldier wrote to his mother, “I come back to you changed.

” The Americans did not beat me. They shook my hand. They did not starve me. They gave me bread until I was ashamed to eat it. They did not humiliate me. They let me work. They paid me. They treated me as if I were still a man. Another described the cowboys specifically. They live harder than we do, but freer.

Their discipline comes not from fear, but from respect. I think of them often. It was in those small moments, moments that seemed insignificant at the time, that the transformation deepened. A handshake after a long day of hanging. A slice of watermelon shared in the heat of August. A harmonica tune drifting across the fence carried on the prairie wind.

For some it was the sound of boots on a wooden porch, spurs ringing faintly like bells. For others it was the sight of a cowboy tipping his hat without arrogance, a gesture of courtesy so simple it lodged in memory like a splinter. The Americans had not intended to change them. The cowboy was not a missionary, not a propagandist. He simply was.

His presence, his ease, his dignity were enough. The prisoners began to tell themselves stories about him. Half inest, half in reverence. They said he feared no officer because he bowed to none. They said his land was so wide he could never be cornered. They said his strength was not in muscle alone, but in the calm way he faced the horizon, as though nothing could break him. These were not official lessons, not written down in Geneva regulations.

They were impressions absorbed quietly that reshaped how the Germans saw both America and themselves. When they returned to Europe, many carried these impressions like contraband. Postwar Germany was a land of rubble, ration cards, and cold winters. Yet in their minds there were still fields of wheat under the Nebraska sun, still the bitter smell of endless coffee in tin mugs, still the sight of men who worked hard without cruelty. Some even sought to recreate fragments of that life.

Cowboy clubs sprang up in West Germany during the 1950s, where men dawned hats, strummed guitars, and dreamed of the planes they had once seen through barbed wire. A few even named their farms with English words. quietly paying tribute to the land that had once held them prisoner, but had given them dignity. Historians who have studied their letters and memoirs agree.

The encounter with cowboys left a mark deeper than most realized at the time. It was not that every German abandoned old ideologies or embraced American democracy. But seeds were planted, seeds of doubt about the myths they had been fed, seeds of admiration for a way of life that seemed both foreign and enviable. As one former P admitted decades later, I went to America an enemy.

I left not a friend perhaps, but with respect. The cowboy taught me more about freedom than any general. The Americans themselves often downplayed it. For them, it was simply the right thing to do. follow the Geneva Convention, feed the men, let them work, keep the peace. But perhaps unknowingly, they demonstrated something more profound, that power need not crush, that strength could be quiet, that freedom could be embodied in the everyday life of a rancher who tipped his hat and carried his tools.

Yet for the prisoners, this generosity brought not only gratitude, but also shame. They knew their families had suffered under bombing, starvation, and fear while they had eaten beef stew and played soccer behind fences. This guilt lingered, pressing on their consciences. Some confessed they dreaded returning home, feared admitting how well they had lived in the enemy’s hands.

One man said bluntly, “We lived better in captivity than our people did in freedom. What does that say of us?” The question could not be easily answered. It haunted them as they boarded trains once more as the wheels carried them east as the land of cowboys receded behind them.

At the docks they looked back toward the horizon where they had first arrived years earlier. Some carried books they had studied in camp. Others carried small carvings of horses, gifts made from scraps of wood. Many carried only memories, but all of them carried the question of what freedom truly meant, and why they had only tasted it in defeat. The trains rolled on through windows.

The prisoners watched the American countryside pass one last time, fields golden with harvest, cattle grazing lazily, small towns with white church steeples. A boy waved at the train, not knowing the men inside were the enemy his father had fought. A cowboy on horseback appeared briefly, silhouetted against the sky, then vanished into the dust. The prisoners pressed their faces to the glass as though trying to fix the image forever.

Years later, in interviews and memoirs, many still spoke of that image, not of the battlefields of North Africa or the ruins of Berlin, but of a cowboy leaning on a fence, spurs shining in the sun. The memory carried both comfort and disqu, a reminder that their war had ended not in brutality, but in a quiet lesson they had never expected.

And so the story lingers, not in statistics or treaties, but in the paradox of men who discovered freedom while trapped, who met America not through speeches or propaganda, but through the dust, sweat, and calm dignity of cowboys. It is a story of enemies disarmed not by bullets but by bread, by coffee, by handshakes offered across the gulf of war.

The trains disappeared into the east, but the memory remained, carried in the hearts of men who had once believed themselves destined to rule the world. They had met their capttors in boots and hats, and could not forget them. And in that unforgettable image lay a final lingering question. If the cowboy was real, then what else about America was