They Laughed at America’s Worst Fighter — Until It Changed Everything

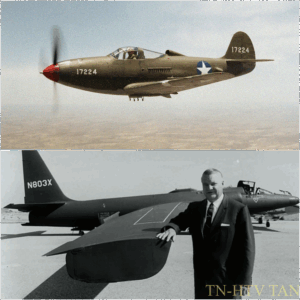

The factory worker’s wrench froze mid turn as he heard the pilot’s words echo across the Buffalo assembly floor. I’m not flying that death trap. It was March 1942 and another test pilot had just walked away from the Bell P39 Ara Cobra. The fifth refusal that week. The aircraft sat gleaming under the hanger lights, fresh paint still drying on its distinctive mid-enine fuselage.

Everything about it looked revolutionary, from its tricycle landing gear to its nose-mounted 37 mm cannon. But the men who were supposed to fly it into combat had another name for the revolutionary design. They called it the flying coffin. What made this rejection particularly devastating was the timing. America desperately needed fighters.

The factories in Buffalo were running three shifts, 7 days a week, trying to build enough aircraft to turn the tide against Germany and Japan. Yet, here was a brand new fighter that nobody wanted to fly. British pilots had tested it and cancelled their orders. The French never even received theirs before their country fell.

American pilots took one look at the specifications and requested transfers to anything else. Even the manufacturer’s own test pilots were starting to have second thoughts. The problem wasn’t immediately obvious to someone looking at the aircraft. The P39 was sleek, modern, and packed more firepower than almost any fighter in production.

That 37 mm cannon could punch through armor plate like tissue paper. The design was actually brilliant in theory. By moving the Allison engine behind the pilot, Bell aircraft’s engineers had created perfect weight distribution and opened up space in the nose for that devastating cannon. A long drive shaft ran beneath the cockpit floor, connecting the engine to the propeller through a complex series of gears and bearings.

But theory and reality had diverged catastrophically. That drive shaft created vibrations that rattled through the entire aircraft, making precision flying nearly impossible. Pilots described it as sitting on top of a washing machine, running at full speed. Worse, the engine placement meant that any mechanical failure sent metal fragments and flames directly toward the cockpit.

In a conventional fighter, engine problems happened in front of you, where you could see them coming. In the P39, they happened behind you, often with no warning until fire started licking at your back. Before we continue, I’d love to know where you’re watching from and what you know about the Eastern Front Air War. Drop a comment below and let me know if you’d heard about the P39’s incredible Soviet service before.

And if you’re enjoying these deep dives into World War II aviation history, hit that subscribe button so you don’t miss the next one. These stories take serious research to get the details right, and knowing you’re out there makes it all worthwhile. The aircraft’s most damning flaw became apparent the moment pilots tried to climb.

The Allison Fe 1710 engine, powerful at sea level, choked and wheezed above 12,000 ft. This wasn’t just an inconvenience. This was a death sentence. German Messersmidt BF109s cruised comfortably at 25,000 ft. Japanese Zeros operated even higher. A P39 pilot trying to intercept enemy bombers would find himself struggling for altitude while enemy fighters dove on him from above with all the advantages of speed and position.

Colonel Bruce Holloway evaluating the P39 for combat deployment in early 1942 wrote a scathing assessment that circulated through Army Air Force’s headquarters. The aircraft is fundamentally unsuited for the high alitude interception role for which it was designed. Its ceiling is inadequate. Its rate of climb is poor above 10,000 ft.

and its handling characteristics at altitude are dangerous. I cannot in good conscience recommend this aircraft for combat operations against the Luftvafa. That assessment should have killed the program. In any rational procurement system, an aircraft that couldn’t perform its intended mission would be cancelled and the factory would retool for something more promising.

But rationality had little place in wartime production. The United States was still reeling from Pearl Harbor. Factories were being built, workers were being trained, and production lines were being established. Cancelelling the P39 would mean shutting down an entire manufacturing operation and starting over from scratch.

The time lost would be measured in months, perhaps years. So, the factories kept running. Workers in Buffalo continued riveting together airframes, installing engines and mounting weapon systems on aircraft that American and British pilots refused to fly. By the spring of 1942, hundreds of P39s were rolling off production lines with nowhere to go.

They sat in storage fields across the country. rows of unwanted fighters gathering dust while the war raged on without them. Then came an unexpected solution. The Soviet Union, fighting desperately against the German invasion, needed aircraft. Any aircraft. Joseph Stalin had made it clear through diplomatic channels that he needed fighters, bombers, and tanks in massive quantities, and he needed them immediately.

The United States, eager to support its ally and keep the Eastern Front active, began shipping military equipment through the lend lease program. Among those shipments were hundreds of P39 Aracobras that nobody else wanted. American officials privately viewed this as a way to dispose of an embarrassing mistake while technically fulfilling their obligations to the Soviets.

The thinking went something like this. Send them the fighters we can’t use, keep the good stuff for ourselves, and hope the Russians can find some use for them. If the P39s proved as inadequate on the Eastern Front as they had in American hands, well, at least the loss wouldn’t be American pilots.

The aircraft began their journey in the most roundabout way imaginable. They were loaded onto cargo ships in American ports, sailed through yubotinfested waters to Persian Gulf ports, then disassembled and transported overland through Iran into southern Russia. The journey took months. Many aircraft were damaged in transit.

Some were lost to German submarines. But by late 1942, the first P30s were arriving at Soviet air bases, where they received a reception very different from what they had experienced in America. Soviet pilots approached the Araco Cobra without preconceptions or prejudices. They didn’t care about high altitude performance because they weren’t fighting at high altitude.

The air war over the eastern front was brutal, chaotic, and conducted primarily below 10,000 ft. German stucokas divebombed Soviet positions at low level. Soviets attacked German tanks at treetop height. The desperate swirling dog fights that characterized Eastern Front combat happened in the thick air where the P39’s Allison engine performed beautifully.

The first Soviet units to receive the Araco Cobra, treated it as an experiment. Pilots accustomed to flying the Leg 3, a wooden fighter that was underpowered and poorly armed, found the P39 to be a revelation. That 37 mm cannon could destroy a German bomber with a single well-placed shot. The aircraft’s sturdy construction meant it could absorb battle damage that would have torn apart the fragile Loi G’s.

And in the lowaltitude environment where Soviet pilots operated, the P39 was actually faster and more maneuverable than many German fighters. Senior Lieutenant Gregori Rekaliff was among the first Soviet pilots to fly combat missions in the Ara Cobra. His initial assessment filed in October 1942 revealed the cultural differences in how pilots evaluated aircraft.

The American machine is heavy but solid. It does not climb well, but it dives like a stone. The cannon is magnificent. Today, I destroyed a Junker’s Jew 88 with three shells. The entire tail section separated from the fuselage. This aircraft rewards aggression and punishes hesitation. That philosophy, aggression rewarded and hesitation punished, became the foundation of Soviet Aracobra tactics.

Pilots learned to use the aircraft’s strengths while avoiding situations that exposed its weaknesses. They attacked swiftly from advantageous positions, fired that devastating cannon, and broke away before enemy fighters could respond. In the hands of pilots who understood its capabilities, the P39 transformed from flying coffin to lethal predator.

The pilot who truly mastered the Araco Cobra was Alexander Ivanovich Pokushkin, a name that would become legendary in Soviet aviation history. Born in 1913 in Nova Subirk, Pokushkin had started the war flying obsolete Y-16 fighters, struggling against superior German aircraft with outdated equipment and tactics. When he transitioned to the P39 in early 1943, he immediately recognized its potential.

Pukrishkin developed a tactical system specifically designed around the Araob’s capabilities. He called it the formula for air combat, a methodical approach that emphasized altitude advantage, speed management, and precise gunnery. His pilots would patrol at medium altitude around 15,000 ft, watching for German formations below.

When they spotted targets, they would dive, building tremendous speed, close to pointblank range, fire a brief burst from the 37 mm cannon, then zoom climb away, using their momentum before enemy fighters could react. The tactic was devastatingly effective. Pushkin’s personal score began climbing rapidly. Five kills, then 10, then 20.

By the time the Battle of Kursk erupted in July 1943, he was the Soviet Union’s leading ace, and his unit flying Americanbuilt Aracobras was one of the most effective fighter regiments in the Red Air Force. German pilots began recognizing his radio call sign and warning each other when Pokushkin was airborne.

Octung Pokushkin Indu became a common transmission on German frequencies. The battle of Kursk demonstrated the P39’s capabilities on a massive scale. German forces launched their final major offensive on the eastern front, committing thousands of tanks and aircraft in an attempt to encircle and destroy Soviet forces near the city.

The Luftvafa deployed its best units, expecting to achieve air superiority quickly. Instead, they encountered Soviet fighter regiments equipped with P39s flown by pilots who had spent months perfecting their tactics. During the first week of the battle, Hishkin’s regiment claimed over 100 German aircraft destroyed.

His personal tally for July 1943, reached 23 confirmed kills. The German offensive, which had counted on air superiority to protect ground forces, found itself constantly harassed by Soviet fighters that appeared, struck, and vanished before the Luftvafa could respond effectively. The P39’s heavy armament proved particularly effective against German J87 Stooka dive bombers, which were slow and vulnerable to the cannon’s devastating firepower.

Reports of the P39’s success on the Eastern Front began filtering back to American intelligence agencies by mid 1943. The assessments were initially met with disbelief. The same aircraft that American pilots had rejected as unsuitable for combat was reportedly one of the most effective fighters in Soviet service.

Some analysts dismissed the reports as Soviet propaganda designed to make their American allies feel better about sending obsolete equipment, but the evidence was overwhelming. Soviet requests through lend lease channels specifically asked for more P39s, not P-51 Mustangs, not P-47 Thunderbolts, but more of the supposedly inadequate Araco Cobras.

By 1944, the Soviet Union was receiving thousands of P39s, and Soviet aces were using them to compile scores that rivaled the best American and British pilots. Pushkin would end the war with 59 confirmed kills, all achieved in Americanbuilt fighters, primarily the P39. The reason for this dramatic difference in performance came down to operational environment and tactical philosophy.

American fighter doctrine in 1942 emphasized highaltitude bomber escort and interception. The P39 had been designed for exactly that role and it failed miserably. Soviet doctrine emphasized lowaltitude ground attack and tactical air superiority. For that mission, the P39 was nearly perfect.

The same characteristics that made it unsuitable for one type of warfare made it ideal for another. Back in the United States, Bell aircraft’s engineers were absorbing lessons from the P39’s contradictory reputation. The aircraft’s failures had exposed critical design flaws, but its successes had validated certain innovative concepts.

The tricycle landing gear, initially controversial, proved far superior to conventional tail dragging designs. It provided better visibility during takeoff and landing, reduced ground loop accidents, and made the aircraft easier for inexperienced pilots to handle. The company began work on an improved version, designated the P63 King Cobra.

This aircraft retained the P39’s basic layout, but featured a more powerful engine, improved aerodynamics, and modifications based on combat feedback from Soviet pilots. The P63 would never see significant American combat service. But like its predecessor, it would be shipped to the Soviet Union in large numbers and prove highly effective in Soviet hands.

More importantly, the lessons learned from the P39’s design influenced the next generation of American fighters. The tricycle landing gear became standard on virtually all subsequent American aircraft. The emphasis on pilot visibility, which Bell had pioneered with the P39’s car doorstyle cockpit entry, became a priority in fighter design.

The concept of mounting heavy, slowfiring weapons in the nose, validated by the P39 success with its 37mm cannon, influenced armament choices for years to come. When Lockheed’s Clarence Kelly Johnson began designing America’s first operational jet fighter, the P80 Shooting Star in 1943, the aircraft that emerged bore striking similarities to the P39’s layout.

Both featured tricycle landing gear for improved handling. Both emphasized pilot visibility and ease of maintenance. Both placed the engine behind the pilot. Though in the P80, this was necessitated by jet engine design rather than a desire to mount a nose cannon. The P80 represented everything the P39 had tried to be but couldn’t quite achieve.

Taking the good ideas while eliminating the flaws. The connection between the despised P39 and America’s jet age success wasn’t coincidence. It was evolution driven by hard lessons learned from both failures and successes. The P39’s failure at high altitude forced American engineers to understand the critical importance of engine supercharging and performance across the entire operational envelope.

Its success in Soviet hands taught that there was no single definition of an effective fighter aircraft. Mission requirements, operational environment, and tactical doctrine all influenced what made a design successful. Alexander Pushkin, the Soviet ace who had mastered the P39, ended the war with 59 confirmed victories, making him the second highest scoring Allied ace after Ivan Kojadub’s 62 kills.

He was awarded the hero of the Soviet Union three times, the highest honor the nation could bestow. In his post-war memoirs, he wrote extensively about the Arachic Cobra, describing it as the finest fighter he had ever flown. The American machine taught me everything important about air combat. It rewarded skill and punished mistakes.

It gave me the tools to survive and the weapons to destroy my enemies. More than 4,700 P39s were delivered to the Soviet Union during the war, representing nearly half of all Aracobras produced. Soviet pilots flew them from Stalenrad to Berlin, racking up thousands of victories against the Luftvafa. These were the same aircraft that American and British pilots had rejected as unsuitable for combat.

The same flying coffins that test pilots had refused to fly. In Soviet hands, they became instruments of victory. The production lines in Buffalo finally shut down in August 1944 after producing 9,584 P39s in various configurations. The workers who had built them probably never knew the full story of how their aircraft had performed in combat.

They had read the negative reports from American pilots, heard the criticisms, and understood that the fighters they were building were considered failures by their own military. They couldn’t have known that on the Eastern Front, those same fighters were helping turn the tide of the largest land war in history.

By 1950, the P39 had disappeared almost entirely from military service. Jets had taken over completely, rendering propeller-driven fighters obsolete except in limited roles. Most era Cobbras were scrapped. Their aluminum melted down for other uses. A few survived in museums, preserved as examples of wartime technology.

But the aircraft’s influence lived on in every American fighter that followed, carrying forward the lessons learned from both its failures and its unexpected successes. The story of the P39 Araco Cobra challenges comfortable narratives about technological progress and military superiority. It reveals that success and failure are often context dependent.

That the same design can be both inadequate and excellent depending on how it’s employed. It demonstrates that innovation sometimes comes from unexpected sources and that the path to progress is rarely straight or predictable. American aviation designers who initially mocked the P39’s unconventional layout later adopted many of its features in their jet fighters.

Soviet pilots who received the aircraft as castoffs from their American allies transformed it into one of the war’s most effective weapons. The lessons from this contradiction shaped American aviation for decades, teaching engineers that brilliance and failure often coexist in the same design, separated only by how and where that design is used.

The engineers at Bell Aircraft, who had designed the P39 with such high hopes, never intended to create a controversial failure that would find redemption in Soviet service. They had envisioned an innovative fighter that would dominate aerial combat with its unprecedented firepower and revolutionary layout. When American pilots rejected their creation, calling it a flying coffin, it must have been devastating.

Yet, their design choices, even the ones that failed, contributed to the foundation of American jet aviation. The factory workers in Buffalo, who riveted together thousands of P39s, knowing their product was unwanted by their own military, demonstrated a different kind of courage. They maintained quality and craftsmanship even when building aircraft that their own pilots called death traps.

They kept the production lines running when conventional wisdom suggested the program should be cancelled. Their dedication ensured that when the Soviets needed fighters desperately, aircraft were available to send them. Today, the few surviving P39s sit in museums alongside Mustangs, Thunderbolts, and other celebrated fighters of World War II.

Museum placards typically describe it as an unsuccessful design that found unexpected success in Soviet service. That assessment, while accurate, misses the deeper significance of the aircraft’s story. The P39 represents something more fundamental than success or failure in combat. It represents the messy, complicated reality of technological development, where failures teach lessons just as valuable as successes.

The fighter that nobody wanted ended up teaching American aviation designers everything they needed to know about building the world’s finest aircraft. Its flaws exposed critical gaps in understanding. Its unexpected success in Soviet hands demonstrated that design requirements must match operational reality.

Its innovative features, refined and improved, became standard elements of jet fighter design. The Flying Coffin became the foundation for American air superiority in the jet age. When the North American F-86 Saber, America’s premier jet fighter of the Korean War era, took to the skies in 1947, it carried DNA from the despised P39. The tricycle landing gear that made ground handling safe and predictable.

The emphasis on pilot visibility and cockpit ergonomics. the understanding that fighter design required careful balance between competing requirements. These weren’t abstract principles. They were hard one lessons purchased with the embarrassment of rejection and the unexpected glory of Soviet victories. The story of the P39 Ara Cobra reminds us that history’s judgments are rarely simple or final.

The aircraft dismissed as America’s worst fighter contributed more to American aviation development than many celebrated designs. The flying coffin that pilots refused to fly enabled Soviet pilots to achieve scores rivaling the war’s greatest aces. The failure that should have been cancelled taught lessons that shaped the future of aerial combat.

Sometimes the machines we reject teach us more than the ones we embrace. And sometimes the worst becomes the foundation for the best.