Why This ‘Ugly’ British Pipe Was The Most Feared Weapon In Occupied Europe

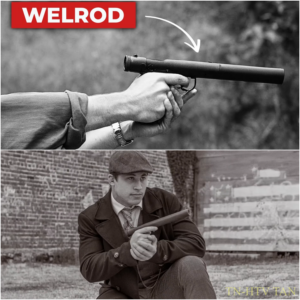

November 1942. A German officer walks through the foggy streets of Copenhagen. He never hears the shot. He never sees the weapon. One moment he’s alive, the next he is dead on the cobblestones, and his killer is already three streets away, the murder weapon tucked inside a coat sleeve. The gun that killed him looked like nothing more than a piece of industrial pipe.

It had no visible trigger guard, no elegant lines, no gleaming finish. It was, by any conventional standard, the ugliest firearm ever issued to British forces. It was also the deadliest covert weapon of the entire war. The Wellrod pistol was never meant to win battles. It was meant to win a different kind of war, one fought in shadows, in occupied cities, in the space between a resistance fighter’s coat and a collaborator’s skull.

and it did so with a sound signature so impossibly quiet that victims often died before anyone realized a weapon had been fired at all. The problem facing British intelligence in 1941 was simple to state and nearly impossible to solve. The Special Operations Executive or SOE had been ordered by Winston Churchill to set Europe ablaze.

Agents were being inserted into occupied territories across the continent. Resistance networks were being organized. Sabotage operations were being planned, but there was one critical gap in the arsenal. When an SOE agent needed to eliminate a target silently, the options were medieval. Knives required getting within arms reach.

Garats required strength and favorable positioning. Poison was unpredictable and slow. What agents needed was a firearm that could kill at close range without alerting every German soldier within a quarter mile. Conventional silenced weapons existed, but they were deeply flawed. The suppressed Sten gun reduced noise to around 130 dB, roughly equivalent to a jackhammer.

Useful for masking the distinctive crack of gunfire, useless for true silent killing. Standard pistol suppressors of the era reduced sound to around 120 dB. Still loud enough to be heard clearly across a street, through walls by anyone within 50 m. SOE needed something that had never existed before. A weapon so quiet it could be fired in a crowded building without drawing attention.

A weapon so simple it could not malfunction at the critical moment. A weapon so compact it could disappear inside clothing. The specification seemed impossible. The task fell to a small team at the Interervices Research Bureau station 9 located in Wellwin Garden City north of London. The lead designers were Major Hugh Reeves and a small group of engineers whose names have been largely lost to classification.

They approached the problem not as gunsmiths but as acoustic engineers. The sound of a gunshot comes from three sources. First, the explosion of propellant gases escaping the barrel. Second, the supersonic crack of the bullet breaking the sound barrier. Third, the mechanical action of the weapon cycling. To achieve true silence, all three had to be eliminated.

The Wellrod team started with the bullet. Standard 9 mm parabellum ammunition travels at around 350 m/s, well above the speed of sound, which is approximately 343 m/s at sea level. Every shot would produce a sonic crack regardless of how well the gases were suppressed. The solution was simple. Use standard 9 mm rounds, but reduce the propellant charge, bringing muzzle velocity down to around 290 m/s.

subsonic, silent in flight. The second problem was mechanical noise. Semi-automatic pistols produce significant sound from their slide cycling, ejecting spent cases, chambering new rounds. The Wellrod eliminated this entirely by using a boltaction mechanism. The shooter manually worked a knurled knob at the rear of the weapon to extract the spent case and chamber the next round.

Slow certainly, but virtually silent. The third and greatest challenge was the propellant gases. When a bullet leaves the barrel, the expanding gases behind it create a miniature explosion at the muzzle. This is what produces the characteristic bang of gunfire. The Wellrod addressed this with an integrated suppressor that was revolutionary in its simplicity and effectiveness.

The suppressor was not an attachment. It was the weapon. The entire front section of the wellrod comprising roughly 2/3 of its length consisted of a series of baffles and expansion chambers. When fired, the propellant gases entered this labyrinth and expanded gradually through multiple chambers, cooling and slowing before eventually venting to atmosphere.

The effect was extraordinary. A standard 9 mm pistol produces approximately 160 dB at the muzzle. This is loud enough to cause immediate permanent hearing damage. The wellrod produced approximately 73 dB. This is roughly equivalent to a car door closing. At 10 m distance, the sound dropped even further, becoming nearly indistinguishable from ambient urban noise.

The weapon itself measured just 14 in in overall length. The grip was a simple cylinder wrapped in rubber to improve purchase, and it concealed a six round magazine. Later versions held eight rounds. The barrel protruded from the front, looking for all the world like a piece of ordinary pipe. There was no trigger guard, just a small curved trigger emerging from the underside.

Sights were minimal, just a fixed front blade and a rear notch because the well rod was never intended for precision shooting at range. The effective range was about 23 m. Optimal range was considerably less. This was a contact weapon designed to be pressed against the target or fired from across a small room.

At these distances, accuracy was academic. What mattered was silence, and in this, the Wellrod succeeded beyond all expectations. Production began in late 1942. The exact numbers remain classified even today, but estimates suggest between 2,800 and 14,000 units were manufactured during the war.

The variance in estimates reflects the extreme secrecy surrounding the program. Serial numbers were deliberately scattered to confuse any attempt to determine production quantities. Documentation was minimal and much was destroyed. The first operational use came in early 1943. SOE agents began receiving wellrods through clandestine supply drops across occupied Europe.

The weapon earned immediate respect among the resistance fighters who used it. In France, the Machi used wellrods for what they called executive actions. German officers who had distinguished themselves through particular cruelty towards civilians tended to die quietly. Collaborators who had betrayed resistance networks stopped talking permanently.

The weapon allowed assassinations in conditions that would have been impossible with conventional firearms. One documented account describes a target being eliminated in a crowded Paris cafe. The killer walked out through a room full of people, none of whom realized what had happened until the body was discovered.

In Denmark, the Hulga Danska resistance group employed wellrods extensively. Their targets included Danish Nazis, Gustapo informants, and German intelligence officers. The silence of the weapon allowed operations in urban areas in daylight in circumstances that would have meant suicide with any louder firearm.

In Norway, SOE agents used wellrods during sabotage operations. Guards could be eliminated without alerting nearby patrols. The seconds of confusion following a silent killing often meant the difference between successful demolition and capture. The psychological impact on German occupation forces was substantial. Officers began to realize that the silence of a room offered no protection.

The absence of gunfire did not mean the absence of danger. Informants became harder to recruit when potential collaborators understood that betraying the resistance might mean death without warning, without sound, without any chance to call for help. If you are finding this interesting, a quick subscribe helps more than you know.

Now, let us examine how the wellrod compared to what the Germans and Americans were developing. German suppressed weapons during this period were primarily adaptations of existing service pistols. The Walter PPK could be fitted with a screw on suppressor that reduced sound to approximately 115 dB. This was quieter than an unsuppressed pistol, but still clearly audible as a gunshot.

More importantly, German suppressor technology was designed for different purposes, primarily reducing shooter signature for snipers rather than enabling assassination in crowds. The Americans produced the HDM or highstandard model D, a suppressed 22 caliber pistol used by the Office of Strategic Services.

This weapon was notably quiet, achieving approximately 90 dB. However, the 22 caliber round limited its effectiveness. Multiple shots were often required to ensure a kill, and penetration through heavy winter clothing was unreliable. The Wellrod’s 9 mm round, even in its reduced powder charge, delivered substantially more stopping power.

A comparison of specifications tells the story clearly. The Wellrodch achieved 73 dB with a 9 mm round. The HDM achieved 90 dB with a 22 caliber round. German suppressed pistols rarely achieved better than 115 dB. In the grim arithmetic of silent killing, the wellrod was in a category of its own. There was one significant limitation.

The Wellrod’s integrated suppressor had a finite lifespan. The rubber wipes that sealed around each bullet as it passed through the baffle stack degraded with