P 47 Thunderbolt: Why The Luftwaffe Laughed At This Plane… Until It Annihilated Them

To the aces of the Luftvafa, the self-proclaimed masters of the European sky. It was a joke. A asterisk Flegenda Milch Flasher asterisk, a flying milk bottle. When the American P47 Thunderbolt first lumbered into view over France in the spring of 1943, German pilots couldn’t help but laugh at its clumsy, bloated frame.

This thing was enormous, weighing up to 8 tons fully loaded, nearly double their nimble Faka Wolf 190s. They figured this airborne juggernaut would be a slow, easy kill, proof of what they saw as crude American engineering. As one German ace later admitted, “We laughed, we made a terrible mistake.” That laughter would soon die in a storm of steel as they discovered the milk bottle was filled with 850 caliber machine guns, a revolutionary engine that owned the high altitudes, and a toughness that was almost supernatural.

They laughed at it right up until it started systematically wiping them from the sky. In early 1943, the air war over Europe was a lethal chess match, and the German Luftvafa were the grand masters. Their fighters were finely honed blades, instruments of precision and speed that had dominated the skies for years.

Into this arena of deadly artists came the American Challenger, the Republic P47 Thunderbolt. And on first glance, it looked like a total bust. It wasn’t just the enemy who was skeptical. American pilots, many fresh out of flight school, took one look at the P47 and were a gasast. When the first planes were assigned to fighter groups in England, like the famed fourth and 78th, the reaction was disbelief.

Many of these guys had been flying the nimble British Spitfire, a thoroughbred of a fighter. The P47, by contrast, felt like a truck. Its cockpit was unusually spacious, which was a small comfort in a plane that felt sluggish and unresponsive. Pilots nicknamed it the Jug because its profile resembled a common milk jug.

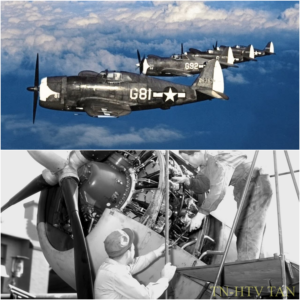

That name would stick, though it would later be recontextualized as short for Juggernaut. The plane’s designer was a brilliant Georgian engineer named Alexander Cartvelli. The US Army Air Corps had tasked him with creating a new interceptor that could take on the Luftvafa’s best. Cartelli’s solution was radical.

Instead of a lightweight dog fighter, he designed his entire aircraft around the most powerful engine he could find, the massive 18cylinder Pratt and Whitney R2800 double Wasp. To make it all work, he added a groundbreaking turbo supercharger system that required a truly enormous airframe. When he presented the design, Cartile himself reportedly said, “It will be a dinosaur, but it will be a dinosaur with good proportions.

” And a dinosaur it was. The P47 weighed nearly 10,000 lb empty. Fully loaded, it tipped the scales at over 17,000 lb. For comparison, the FW190, one of its main rivals, weighed less than 9,000 lb fully armed. This immense weight had immediate and worrying consequences. The Thunderbolts climb rate was poor.

In a classic turning dog fight, it was hopelessly outclassed. It took forever to get off the ground, needing long runways that weren’t always available at forward airfields in England. The Jug’s combat debut on April 8th, 1943 was a disaster. A fighter sweep over France had to be called off because the American radios didn’t work.

A humbling setback that forced the entire fleet to be refitted with British gear. When they finally did meet the enemy, the results were grim. In the first two months, P47s flew over 2,000 missions, but only claimed 10 German planes while losing 18 of their own. Luftwafa pilots learned the playbook fast.

Get the clumsy American giant into a lowaltitude turning fight, and it was an easy kill. The flying milk bottle seemed to be just what they thought, an oversized, underperforming flop. Even the American pilots began to lose faith, especially the veterans of the fourth fighter group who bitterly missed their Spitfires. The Germans watched the arrival of this behemoth not with fear, but with arrogance.

They saw a plane built with brute force in mind, lacking the tactical finesse they prided themselves on. They saw it as proof that Americans just thought bigger was always better. a philosophy they were sure would fail. The laughter in Luftwafa mesh halls was genuine. They’d faced the best the Allies had, and this wasn’t it. But what they failed to grasp was that the P47 wasn’t designed for their kind of fight.

It was designed for a whole new kind of war. And the joke, they would soon discover, was on them. So why were the Germans so wrong? because they were judging the Thunderbolt by their own standards, failing to look deeper and see the revolutionary heart of the beast. The P47’s secrets weren’t in its agility, but in its engine and the incredible system that fed it, allowing it to dominate where it mattered most, the frigid, thin air above 25,000 ft.

The first secret was the engine itself, the Pratt and Whitney R280 double Wasp. This wasn’t just an engine. It was a 2,000 horsepower monument of engineering that would eventually be pushed to over 2,800 horsepower with water injection. For comparison, the superb engine in the BF109 produced around 1,400 to 1,800 horsepower.

The R28000 was, simply put, one of the most powerful piston engines of the war. Its radial design was also the key to the P47’s famous toughness. Unlike the liquid cooled inline engines of the Spitfire or BF 109, a radial engine cylinders are arranged in a circle. This created more drag, hence the P47’s bulky shape.

But it also meant there was no fragile cooling system with long, vulnerable tubes carrying vital fluid. German pilots were used to seeing their cannon shells rip through an engine, sever a coolant line, and watch the plane fall from the sky. The R280, however, was a different animal. It was air cooled, and its sheer mass meant it could absorb an unbelievable amount of punishment.

There are countless stories of P47s returning to base with entire cylinders shot clean off. The engine still chugging along. But a powerful engine alone wasn’t enough. At high altitudes, the air gets thin, starving an engine of oxygen. Most fighters used a geardriven supercharger spun directly by the engine. This worked, but it was a parasite, robbing the engine of power, and its performance dropped off dramatically at high altitudes.

Here’s where the Thunderbolt’s true secret weapon came in. Its General Electric turbo supercharger. Instead of being driven by the engine, the turbo was powered by the engine’s own hot exhaust. Waste energy. A mind-bogglingly complex network of ducts snaked from the engine down the belly of the plane to a turbine in the rear fuselage.

This turbine used the exhaust to spin a compressor at over 20,000 RPM, scooping up thin, cold air, pressurizing it, and ramming it back into the engine. The result was nothing short of miraculous. While German fighters with their mechanical superchargers began to gasp for air above 25,000 ft, the P47’s R2800 was just hitting its stride.

The turbo allowed the Thunderbolt to maintain its immense power all the way up to 30,000 ft and beyond. Up there, in the realm of the high alitude bombers it was built to protect, the clumsy jug became a thoroughbred. It was fast, responsive, and packed with energy its German adversaries just couldn’t match. The Luftwafa aces were being drawn into a new battlefield where all their advantages were stripped away.

The flying milk bottle was revealing its first terrifying secret. It wasn’t built to dance. It was built to hunt in an environment where nothing else could breathe. If the P47’s engine was its heart, its armament was its soul. German pilots used to a balanced philosophy of firepower and ammunition were about to meet an aircraft built on a uniquely American principle, overwhelming unadulterated firepower.

The Thunderbolt carried a staggering 850 caliber M2 Browning machine guns, four in each wing. This wasn’t just a lot of guns. It was a flying artillery battery. With all eight guns blazing, the P47 could unleash over 100 rounds per second. Pilots didn’t describe it as firing guns.

They called it projecting a wall of lead. The ammunition load was just as massive, carrying up to 4,000 rounds. A BF109, by contrast, could exhaust its ammo in just a few short bursts. A Thunderbolt pilot could hold down the trigger for nearly 30 seconds of continuous fire. You didn’t have to be a perfect shot. You just had to get the enemy somewhere in your sights and let the sheer volume of fire do the rest.

The guns were angled to converge at a specific distance, often around 300 yards. Anything caught in that zone, a wing, a cockpit, an engine, would be utterly shredded. The heavy high velocity50 caliber slugs could punch through armor and shatter engine blocks. Luftwafa ace Gunter R described facing this as industrial execution.

It changed air combat from a skilled duel into an act of industrial annihilation. This firepower was mounted on an airframe that could take a terrifying amount of punishment. The P47 was without exaggeration one of the toughest planes ever built. The cockpit was a veritable bathtub of armor plating. The air cooled radial engine, as mentioned, could absorb hits that would have vaporized a liquid cooled engine.

and its sheer size meant enemy rounds could often pass straight through without hitting anything vital. The stories of the P47’s durability are legendary. The most famous is that of Major Robert S. Johnson. On June 26th, 1943, Johnson’s P47 was ambushed and shredded by at least 21 cannon shells and hundreds of machine gun rounds.

His canopy was shattered. His plane was on fire and he was wounded. He tried to bail out, but the damaged canopy was stuck, trapping him inside the burning wreck. In a desperate dive, the flames miraculously went out. As he limped towards the English Channel, a lone FW190 moved in for the kill. Unable to fight back, Johnson braced for the end.

The German pilot made several passes, pouring fire into the helpless Thunderbolt. Finally, out of ammunition, the German pilot pulled up alongside the mangled P47. He looked across at Johnson, rocked his wings in a salute to a man he thought was already a ghost, and turned for home.

Johnson somehow flew that wreck, which had over 200 bullet holes, back to base. This was the Thunderbolts second revelation. It wasn’t just an engine. It was a fortress. Luftvafa pilots, used to seeing targets disintegrate, now faced an enemy that simply refused to die. They’d pour ammunition into the giant American fighter only to watch in disbelief as it stubbornly flew on.

As Luftwafa Ace Hinesbear famously said, the P47 could absorb an astounding amount of lead. The laughter was gone. In its place was a growing sense of dread. They were fighting a monster. The P47 was a weapon waiting for the right tactics. The early fumbles were the result of pilots trying to fight the Luftvafa’s game. A deadly mistake.

But a new generation of shrewd commanders like Hubert Zena of the 56th Fighter Group realized you don’t send a heavyweight boxer to dance ballet. You teach him to use his power. The answer was a tactic as brutal as the plane itself. Boom and zoom. The doctrine was simple. Avoid turning dog fights at all costs.

Instead, P47 pilots used their engine’s phenomenal high altitude performance to climb above their opponents. From this perch at 30,000 ft or higher, they would scan the skies below for German fighters. And once a target was spotted, they would tip over and dive. And in a dive, the P47 was untouchable.

Its immense weight, a weakness in a climb, became its greatest asset. Gravity grabbed the 8-tonon fighter and pulled it down with terrifying force. The Thunderbolt could reach speeds in a dive that would tear the wings off other aircraft, pushing well over 500 mph. At these velocities, the P47 became a guided missile.

The attack was swift and devastating. A P47 would plummet out of the sun, its target often completely unaware until the sky erupted in tracers. The pilot had just a few seconds to line up a shot, squeeze the trigger, and unleash hell. Before the enemy could react, the Thunderbolt would be past him, using its incredible speed to zoom climb back to altitude, ready for another pass.

There was no duel, no graceful exchange. It was a high-speed execution. This tactical shift transformed the P-47’s effectiveness, making it the premier escort for the B17s and B-24s of the Eighth Air Force. Now, German fighters had to fight their way through a ceiling of prowling thunderbolts just to get near the bombers.

By late 1943, German intelligence reports, which had initially dismissed the P47, now identified it as a deadly threat. The aircraft itself was also evolving. One of the most significant upgrades was the bubble canopy. The original razorback design had a huge blind spot to the rear, a fatal flaw. The new teardropshaped canopy gave the pilot an unobstructed 360° view.

Another gamecher was a new paddleblade propeller. Its wider blades bit into the air more effectively, dramatically improving the P47’s takeoff, acceleration, and most importantly, its rate of climb. The sluggish jug they had once mocked could now climb right along with them. With these improvements, the P-47 became a truly formidable fighter.

It had the visibility and climb rate to complement its speed, firepower, and toughness. The days of laughing at the flying milk bottle were a distant, bitter memory. Now, when the Luftwaffa looked up and saw those bulky silhouettes circling high above, they felt a cold knot of fear. The sky was no longer theirs. As 1944 dawned, the new P-51 Mustang began to arrive in Europe.

With its incredible range, the Mustang was perfect for escorting bombers all the way to Berlin and back. For a lesser aircraft, this might have meant obsolescence, but for the Thunderbolt, it was the beginning of a second life, a new calling where its talents for destruction would be unleashed with even greater ferocity.

the role of the fighter bomber, or as the Germans came to call it in terror, the Jabo. The P47’s powerful engine meant it could carry a staggering payload, up to 2,500 lb of bombs, a load that rivaled some light bombers, plus an array of up to 10 5 in high velocity rockets. This transformed the high altitude hunter into a low-level angel of death.

In the leadup to D-Day, Allied air power was tasked with crippling the German war machine, and the P47 was the perfect tool for the job. The effect was cataclysmic. Flying at treetop level, P47s roamed across France, hunting anything that moved. Their targets were the arteries of the German army, railways, supply depots, and troop convoys.

A flight of thunderbolts could appear in seconds. Their 850 cals ripping a column of trucks into a chain of burning wrecks. Their rockets could obliterate a tank. Their bombs could crater airfields. It was in this role that the P47’s legendary toughness became its most vital asset. Low-level attack is incredibly dangerous work, flying directly into a blizzard of ground fire.

But the Thunderbolts rugged airframe and air cooled engine could soak it up and keep flying. P47s would routinely return to base, riddled with holes, trailing smoke, yet their pilots were alive. As one common saying went, “There isn’t a P47 pilot alive who wouldn’t elect to belly one in rather than bail out.

” On D-Day and in the brutal weeks that followed, the P47 became the German soldiers worst nightmare. German tank commanders who once ruled the battlefield were now paralyzed. Moving during daylight invited a swift and violent death from above. The distinctive roar of the R280 engine became a sound of impending doom, inducing a psychological condition among German troops known as Jabo fever.

When the sound of a thunderbolt was heard, soldiers dived for cover, knowing a storm was only seconds away. The statistics are staggering. From D-Day to VE Day, P47 pilots would go on to claim the destruction of 86,000 railroad cars, 9,000 locomotives, 6,000 armored vehicles, and 68,000 trucks. They systematically dismantled the German logistical network, starving the front lines.

As the German commanderin-chief in the west, Gerd von Runstead bitterly complained, Allied air power led by the Jabos had made it impossible to conduct any meaningful troop movements. The joke had become a juggernaut. The story of the P47’s victory isn’t just about technology or tactics. It’s the story of a clash between two totally different philosophies of war.

The German approach relied on a core of highly skilled, irreplaceable aces. The American approach was one of industrial overwhelming force. The P47 was the perfect symbol of this doctrine. The sheer number of thunderbolts produced is hard to even comprehend. Between 1941 and 1945, Republic Aviation churned out over 15,600 P47s. At its peak, a new Thunderbolt was rolling off the assembly line every hour.

This was an industrial tsunami the German war machine simply could not counter. While German factories struggled under constant bombing to produce a few hundred fighters a month, America was burying them under an avalanche of steel. This miracle extended to every part of the plane. Over 125,000 of the R2800 engines were built, not just by Pratt and Whitney, but by car giants like Ford and Chevrolet.

This ensured a limitless supply of planes and spare parts. When a P47 was damaged, it was often repaired and flying in days. When a German fighter was lost, its replacement was uncertain, and the loss of its pilot was a catastrophic blow, and the pilots themselves were another product of this industrial scale approach. While the Luftwafa’s training program withered from fuel shortages and constant combat, the US Army Air Forces built a vast training pipeline.

Before ever seeing combat, an American pilot received hundreds of hours of flight instruction. In stark contrast, by late in the war, a new Luftwaffa pilot was lucky to have 100 hours of total flight time before being thrown into battle. The Americans weren’t just building more planes. They were building more pilots, nearly 200,000 of them.

The loss of a pilot, while a tragedy, was a replaceable cog in a vast machine. The final piece was logistics. The P47 was a thirsty machine, but America’s industrial might ensured that the high octane fuel, the ammunition, and everything else was available in seemingly infinite quantities. This was the war the Luftwafa could never win.

They weren’t just fighting the P47. They were fighting the entire industrial capacity of the United States. The P47 was the steel tipped spear of a juggernaut that ground the Luftvafa into dust through sheer relentless attrition. If you enjoyed this deep dive into one of World War II’s most legendary aircraft, be sure to hit that like button and subscribe to our channel.

We have plenty more stories of incredible machines and the brave people who flew them, and you won’t want to miss out. By May 1945, the Republic P47 Thunderbolt had carved its name into history. The plane once mocked as a flying milk bottle, a clumsy joke, had become a legend. It ended the war with an official killto- loss ratio of over 4:1, having flown over half a million missions and destroying thousands of enemy aircraft and tens of thousands of vehicles.

Its journey from underdog to dominator was a story of adaptation, of ruthlessly exploiting its strengths. It was a story of technological innovation, harnessing the power of a revolutionary engine to conquer the high alitude frontier. And above all, it was a story of industrial philosophy, proving that wars are won not just by tactical brilliance, but by the relentless, overwhelming power of mass production.

Perhaps the ultimate testament came from Germany’s general of fighters, Adolf Galland. When asked what truly defeated the Luftvafa, he didn’t point to a single battle. He pointed to the sky over Germany, darkened by swarms of American fighters that could hunt his own pilots to extinction. The P47 was the brutal instrument of that dominance. Its legacy lives on.

The P47’s design philosophy, a heavily armed, incredibly tough aircraft built to support ground troops, has a direct spiritual successor, the Fairchild Republic. A 10 Thunderbolt 2, better known as the Warthog. The story of the P47 is a perfect reversal of fortune. It begins with laughter and ends with fear.

It starts as a joke and finishes as a juggernaut. It’s a timeless reminder that in the deadly calculus of war, the most underestimated weapon can often become the most decisive