The Disturbing True Origins of Snow White

Do you think you know Snow White, the jealous stepmother, the magic mirror, the seven dwarfves, the poisoned apple? But the fairy tale you’ve been told is a lie that’s been cleaned up over hundreds of years. The original story wasn’t written to entertain children. It was written to warn them about a danger so real and so terrible that people couldn’t speak about it directly.

Today, we’re uncovering the disturbing truth hidden in Snow White’s story. a coded message about actual crimes that people in medieval Germany would have readily understood. And here’s what will stick with you. Once you learn what the glass coffin really meant in medieval Germany, once you understand why the original villain was Snow White’s actual mother, you’ll realize this was never just a fairy tale.

It was proof of something much worse. Let’s begin. The version the Brothers Grim first collected wasn’t about a stepmother at all. In their original 1812 manuscript, the woman who orders Snow White’s death, who demands her organs be cut out and delivered as proof, who then boils those organs in salt and eats them thinking she’s consuming her own daughter’s flesh.

That woman was Snow White’s biological mother. Picture the Grims writing by candle light in their study in castle, carefully transcribing what elderly peasant women had whispered to them. On the yellowed page in Jacob Grim’s precise handwriting appears the German word die mutter, notif stepmother, simply mutter mother.

The manuscript preserved now in the Berlin State Library shows no hesitation, no correction. This mother orders her huntsman to bring back her seven-year-old daughter’s l//u//ng///s and l//i//ve//r. And when he delivers what she believes are Snow White’s organs, she doesn’t just dispose of them. The text explicitly states, “The cook had to boil them in salt, and the wicked woman ate them up.

She consumed them greedily, believing she was devouring her own child’s essence. This wasn’t a transcription error or a momentary lapse. Across Europe, from Russia to Ireland, folklorists have documented similar tales of maternal cannibalism, stories that emerged from very real fears about what mothers might do to daughters who threatened their position.

The Grimms changed this detail in later editions, transforming the mother into a stepmother to make the story more palatable. But they couldn’t erase what folklore scholars now recognize as the tale’s true origin. A coded warning about infanticide and the very real dangers young girls faced within their own households during an era when a daughter’s beauty could be seen as either an asset to be traded or a threat to be eliminated.

But if the image of a mother devouring her child’s flesh wasn’t disturbing enough, the horror doesn’t stop at the family table. What the Grims captured was only the beginning of a far darker reality. One where daughters weren’t just victims of jealousy, but porns in a ruthless game of power, wealth, and survival.

Consider the historical context that medieval audiences would have immediately understood. In the German territories where this tale originated, young noble women like Snow White were political porns, their beauty determining their value in marriage alliances. But here’s where the historical record becomes genuinely disturbing.

When a young daughter’s beauty surpassed her mother’s, it could shift the balance of power within noble households. The mother’s influence derived from her ability to broker marriages and maintain court relationships suddenly faced competition from her own bloodline. Take the case of Margareta von Waldec documented in Bavarian court records from the 16th century.

At age 13, her sudden wasting illness occurred just weeks after her betroal to a powerful duke, a match that would have elevated her above her mother’s station. The court physicians notes, discovered centuries later in monastery archives, hint at symptoms consistent with mercury poisoning. Her mother inherited not only Margarita’s dowy, but also the right to negotiate a new alliance with the spurned Duke’s family.

No investigation was ever conducted. The father, who stood to gain significant lands from his wife’s new negotiations, declared it God’s will. Such cases weren’t aberrations, but patterns whispered about in castle corridors, but never formally prosecuted, creating an atmosphere where every young noble woman knew that her emerging beauty might mark her for d//ea//th.

The mirror in the story, that wasn’t magical thinking to medieval listeners. The elaborate mirrors of noble households were genuine status symbols costing more than entire estates. They represented not just vanity, but political power. The ability to maintain one’s appearance was directly tied to maintaining one’s position at court.

When the mirror declares Snow White the fairest, it’s not offering a compliment. It’s pronouncing a death sentence, announcing a transfer of power that the queen cannot accept. And then we come to the huntsman ordered to bring back Snow White’s lungs and liver as proof of death. Modern readers miss the devastating significance of these specific organs.

In medieval German folklore, the lungs were believed to contain the breath of life, the very essence of youth, while the liver housed the soul’s vitality. The queen doesn’t just want Snow White dead. She wants to consume the physical sources of her daughter’s beauty and youth. The text explicitly states, “She boils them in salt and eats them, engaging in a ritual that anthropologists have identified in multiple cultures as symbolic vampirism.

The belief that consuming another’s organs transfers their qualities to the eater. But the truly brilliant horror of this tale emerges when you examine what happens after Snow White escapes. Snow White doesn’t flee to safety. She enters servitude with seven men in the forest. The Grimms were careful to call them dwarfs, but folklore historians have uncovered something far more unsettling.

In the Hessian regions, where the Grims collected their tales, historical records from the 16th and 17th centuries document the extensive use of child labor in mining operations. Children as young as seven were sent into mines because their small bodies could navigate narrow tunnels. They were called Kleinenberg loiter, literally small mountain people, which the Grimms translated as dwarfs.

Imagine children no older than Snow White herself, crawling on hands and knees through passages barely wider than their shoulders, their lungs burning with coal dust and toxic fumes. The mining archives from Zean dated 1618 describe boys and girls who entered the mines at 7 and if they survived emerged permanently stunted, their growth arrested by malnutrition and the crushing weight of the earth above them, their spines curved from years of crouching in three-foot high tunnels, their skin, deprived of sunlight, turned the palar of mushrooms. At night, these

child miners slept in communal barracks hidden deep in the forest, far from the towns whose wealth they dug from the earth. Local girls, often runaways or orphans themselves, would keep house for these communities in exchange for protection and shelter. When Snow White arrives at the cottage and immediately begins cooking and cleaning for seven small men who work all day and return covered in grime, contemporary audiences would have recognized this arrangement instantly.

The seven dwarfs weren’t magical beings. They were society’s most exploited children, and Snow White had joined their ranks, trading domestic servitude for survival. The three murder attempts that follow reveal an escalating pattern that modern criminologists recognize as classic predatory behavior. First, the queen arrives disguised as a peddler woman selling bodice laces, seemingly innocent items that she uses to suffocate Snow White by lacing her too tightly.

When that fails, she returns with a poisoned comb, a more direct attack on Snow White’s beauty itself. Finally, the apple. Red on one side, white on the other, poisoned on the red side. The queen eats the white half to prove it’s safe, then watches as Snow White bites into the red portion. That apple deserves special attention because it connects to one of the most chilling aspects of the historical record.

In medieval Germany, there was a documented practice among those who dealt in poisons. The creation of what were called Judas fruits. Apples or other fruits partially injected with poison designed to kill slowly enough that the poisoner could establish an alibi. Picture a feast in the great hall of ainand castle. Circa 1485.

The servants bring forth a silver platter bearing perfect red apples, their skins gleaming in the torch light. The hostess herself selects one, cuts it with her own knife, and eats half while offering the other to her young rival. Hours later, long after the hostess has retired to her chambers, with witnesses to her own good health, the victim begins to convulse.

Her lips remain red, her skin stays fresh, but her body seizes into paralysis. The court physicians examining her find no obvious cause of death. The apple long since digested. The poisoner’s alibi unshakable. These Judas fruits, named for the betrayer, who shared bread with Christ before destroying him, were infamous enough that Italian diplomat Lorenzo Demedi wrote warnings about them to his allies.

The symptoms Snow White displays, immediate paralysis, preservation of her beauty, the appearance of death while potentially maintaining minimal life signs, match exactly the effects of concentrated Belelladona extract derived from deadly nightshade plants that grew wild in German forests. The poison would cause the pupils to dilate, creating an appearance of beauty, the muscles to freeze, and the heart to slow to nearly imperceptible beats.

The glass coffin, where Snow White lies in suspended animation, wasn’t a fairy tale invention either. Noble families across Europe actually commissioned crystal or glass topped coffins for young women who died under suspicious circumstances, particularly when questions of inheritance or succession were involved. The transparent coffin served a triple purpose.

It proved the heirs was truly dead, preventing any rival claims that she had been hidden away. It displayed her beauty one final time, a morbid advertisement of the family’s genetic stock, and it prevented anyone from examining the body too closely for signs of foul play, the glass created an impenetrable barrier between the victim and any who might question the cause of death.

When Snow White lies in her crystal coffin, beautiful and untouchable, she joins a long line of noble daughters whose deaths enriched their families and whose bodies became public spectacles of private crimes. The glass coffin may have preserved Snow White’s body as proof of death. But it also invited something far worse. By turning her into a permanent display, the tale sets the stage for an even more unsettling consequence.

The arrival of a prince whose fascination isn’t with life, but with beauty frozen in death. In the Grim original, Snow White isn’t awakened by true love’s kiss. A prince becomes obsessed with her corpse, yes, her corpse, and convinces the dwarfs to give him the glass coffin. He has his servants carry it everywhere he goes. And when they stumble, the jostel dislodges the apple from her throat.

She awakens not from love, but from pure accident after being treated as an object of necrilic obsession. The wedding that follows brings us to the tale’s final revelation of justice that would have resonated with medieval audiences in ways we’ve forgotten. The evil queen is forced to dance in red-hot iron shoes until she dies.

A punishment that wasn’t fantasy, but historical fact. This specific execution method was reserved in medieval law for one particular crime, matraide, or attempted matricade. This wasn’t just capital punishment. It was a theatrical display meant to demonstrate that certain crimes violated the natural order so fundamentally that they required supernatural levels of retribution.

When the evil queen faces this fate in Snow White, every listener would have understood. Her crime was recognized as the most heinous possible, the destruction of one’s own bloodline. And the tale was granting her the justice that real mothers who murdered their daughters so rarely faced. Maria Tatar, the Harvard folklorist, who spent decades studying the brothers grim manuscripts, made a discovery that transforms our entire understanding of this tale.

In the margins of their working notes, the brothers had written Mahnung un Vanung Snow White reminder and warning. This wasn’t meant to be entertainment. It was meant to be a cautionary tale encoding real dangers that young women faced, preserving knowledge of actual crimes that were too horrible to speak of directly. The tale even embeds a sophisticated understanding of what we now recognize as intergenerational trauma.

The magic mirror doesn’t just reflect physical beauty. It reflects the queen’s psychological state, her inability to see her daughter as anything but competition. Modern psychologists studying the tale have noted that the queen’s behavior follows the pattern of what we now call malignant narcissism, the inability to tolerate being surpassed, even by one’s own children.

But the Grimms understood this centuries before psychology had a name for it. They preserved in symbolic form a warning about mothers who would rather destroy their daughters than see them flourish. And once you understand that the grims were encoding a warning rather than spinning a bedtime story, the smallest details of the tale take on a terrifying new weight.

Even the numbers themselves were chosen with precision, carrying legal and spiritual meanings that medieval audiences would have recognized instantly. Seven dwarfs, three murder attempts, one apple divided in two halves. These weren’t random choices. In medieval numerology, seven represented completion or perfection. Seven deadly sins, seven virtues, suggesting Snow White’s time with the dwarfs was a complete cycle of hiding.

Three attempts indicated a fairy tale pattern. Yes, but also matched legal precedent. Under Germanic law, three attempts at murder elevated the crime to high treason when the victim was of noble blood. The bifocated apple, white and red, safe and poisoned, embodied the duality the entire tale explores. The mother who should protect but instead destroys.

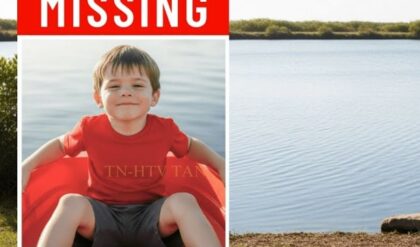

The beauty that should be celebrated but instead incites murder. The home that should be safe but becomes the source of greatest danger. But perhaps the most devastating detail is one that appears in the earliest versions but was gradually edited out. Snow White’s age. In the 1812 version, she’s 7 years old when her mother first tries to kill her. Seven.

The same age at which children entered servitude in the mines. The same age at which, under medieval law, a girl could be betrothed. The same age at which, according to court records from the period, young girls of noble birth begin to appear in historical documents as victims of mysterious illnesses or accidents that benefited their mother’s political positions.

This wasn’t a story about a teenager threatened by her stepmother’s vanity. This was about systematic child abuse encoded and preserved in a form that could be safely transmitted through generations. The brothers grim as legal scholars would have seen the court records. They would have known about the investigations that never went anywhere.

The young girls who disappeared or died under suspicious circumstances, the mothers who inherited their daughter’s dowies or marriage prospects. They took that horrific reality and wrapped it in just enough fantasy to make it tellable, but left enough truth that anyone who knew where to look could see the warning underneath.

The forest where Snow White flees isn’t just a physical location. It’s a psychological space representing the nowhere that existed for young women who fled abusive households. They couldn’t return home. They couldn’t seek legal protection as their fathers or mothers were their legal guardians. And they couldn’t survive alone.

The mining communities represented one of the few places where questions weren’t asked, where a young woman could trade labor for protection. Where the authorities didn’t venture. The Brothers Grim preserved this underground railroad of the medieval period, hidden in plain sight as a fairy tale cottage. Even the seemingly innocuous detail of Snow White’s coloring, skin white as snow, lips red as blood, hair black as ebony, encoded a warning that would have been crystal clear to medieval audiences.

These weren’t just poetic descriptions. They were the exact features that marked a young woman as valuable in the marriage market of medieval Germanic courts. The specific combination marked her as having noble bloodlines, the pale skin indicating she didn’t work outdoors, youth and health, the red lips suggesting vitality and fertility.

Black hair being associated with youth as it would gray with age. Snow White is marked from birth as a valuable commodity, and her tale shows how that very value makes her a target. But beauty wasn’t just a death warrant in the marriage market. It seeped into every gesture of daily life. Nowhere is this more chilling than in the moment when what’s supposed to be a symbol of a mother’s tender touch becomes a deadly weapon.

The poisoned comb that the queen uses in her second murder attempt deserves particular attention. Combs in medieval noble households weren’t simple grooming tools. They were intimate objects often passed from mother to daughter carrying familial significance. A mother combing her daughter’s hair was a daily ritual of bonding and care. By transforming this symbol of maternal love into a weapon, the tale makes explicit what it has been suggesting all along, the complete perversion of the motheraughter relationship, where every gesture of care might be an attack in

disguise. Folklorists have found versions of Snow White across cultures, from Italy to Africa to Malaysia, but the German version collected by the Grimms is unique in its systematic encoding of specific medieval dangers. The Italian version, the young slave, has the girl fall into enchanted sleep but lacks the cannibal mother.

The Scottish version has the stepmother as villain but omits the mirror entirely. Only the German version combines all these elements into a comprehensive warning system about the dangers young noble women faced within their own families. Other cultures told their own versions of the tale, but none carried the same deliberate brutality as the German variant.

And that’s because the Grimms weren’t just recording folklore. They were preserving fragments of real crimes hidden inside a fairy tale. The academic Victoria Duda’s recent analysis of the grim manuscripts revealed something extraordinary. marginal notes suggesting the brothers were actively collecting testimonies from elderly women who claimed to remember true versions of the tale from their grandmothers.

These oral histories, fragments of which survive in university archives, consistently emphasize the same elements. The mother, not stepmother, as villain, the specific organs demanded as proof of death. The mining communities as refuge, and most chillingly, insistence that this happened or this was real. The Grims weren’t just collecting folklore.

They were preserving testimony, encoding historical crimes into a narrative that could survive where legal documents might be destroyed. The transformation of this tale into children’s entertainment represents one of the most successful acts of historical erasia ever accomplished. Each adaptation moved further from the source material’s darkness.

The Disney version, released in 1937, eliminated every one of the tale’s warning elements. The mother became unambiguously a stepmother. The dwarfs became comic figures. The prince’s necrilic obsession became true love’s kiss. And Snow White herself transformed from a seven-year-old abuse victim into a singing teenager. The sanitization was so complete that modern audiences have no idea they’re watching a story that originally documented systematic child abuse and attempted filicide.

Yet the darkness persists even in sanitized versions. Children instinctively recognize something wrong with the tale. They ask why the mother wants Snow White dead, why she has to live with strangers, why the prince falls in love with someone he thinks is dead. These questions point to the cognitive dissonance created when a horror story is disguised as a fairy tale.

The darkness bleeds through because it’s structural to the narrative. You can’t remove it without the story collapsing entirely. Beneath the glittering symbols lies a record of real dangers young women faced in medieval households where innocence could be weaponized against them and beauty could become a death sentence. The mirror, the poisoned apple, the glass coffin.

These weren’t playful inventions for children. They were symbols of power, control, and violence drawn from a world where daughters were pawns in political games, and too often victims of the very mothers meant to protect them. The Grimms, trained as legal scholars, knew the court records, knew the whispered accounts, and wrapped those horrors in just enough fantasy to ensure their survival through centuries of retelling.

That’s why the tale endures. It isn’t because of dwarfs or romance. It’s because its DNA carries a truth too terrible to speak plainly. The greatest threat to a child might come from within her own home. Snow White isn’t a bedtime story. It’s a crime scene preserved in narrative form, evidence disguised as entertainment. And once you recognize what you’re really reading, the illusion collapses.

The fairest of them all was never about beauty. It was about a child marked for death.