December 17th, 1944. A checkpoint outside Iweila, Belgium. The jeep rolled to a stop as the military policeman raised his hand, his breath visible in the frozen morning air. Three soldiers sat inside, wearing American uniforms that looked authentic enough, carrying weapons that seemed regulation, speaking English that sounded almost right.

But Sergeant William Creel had been warned about something impossible, something that contradicted everything he knew about warfare and honor. German soldiers might be operating behind American lines, dressed as American troops, speaking American words. He asked for the password. The men hesitated. He asked again. Their English faltered.

Then Creel noticed the Sten guns, British weapons that no American patrol would carry. Within minutes, the three men were in custody. Under their olive drab uniforms, they wore German field gray. Untitia Manfred Perus, Oberfenrig Gunta Billing, and Geita Wilhelm Schmidt had just become the most infamous prisoners of the Battle of the Bulge.

What none of them knew was that their capture would trigger the most widespread paranoia in American military history, a systematic campaign of cultural interrogation that would turn every checkpoint into a quiz show, every conversation into a test of American identity, and every soldier into a potential spy. The mathematics of detection were being written not in codes and ciphers, but in baseball statistics, state capitals, and Hollywood gossip.

The exposure had begun on October 22nd, 1944 at Hitler’s headquarters in Rastenberg, East Prussia. Adolf Hitler summoned SS Oashm Banfura Otto Scotsy to his presence, addressing him with words that would reshape the final months of the war. The Furer had a mission, one that would require deception on a scale never before attempted. Scorzeni already stood among Germany’s most feared commandos.

In September 1943, he had led the glider assault that rescued Bonito Mussolini from his mountain prison at Grand Saso, spiriting Ilduche away in a light plane that barely cleared the rocky plateau. In October 1944, he had orchestrated the kidnapping of Miklo Horty Jr., forcing Hungary’s regent to resign and keeping that nation in the war.

Now Hitler presented him with his most audacious assignment yet. German forces would launch a massive counteroffensive through the Arden’s forest, driving toward the crucial port of Antwerp. The attack would split the American and British armies, recreating the stunning victory of May 1940 when German panzas had reached the English Channel in days.

But this time, success depended on speed. The Germans needed to capture at least one bridge over the Muse River intact before Allied engineers could destroy it. Scorzani would form a special brigade, Panza Brigade 150, whose purpose would be to seize those bridges before they could be blown. Hitler informed him of a decision that made even the hardened commando pause.

This could be accomplished more quickly and with fewer losses if Scotseni and his men wore American and British uniforms. Small units disguised in enemy clothing could cause tremendous confusion, Hitler explained, upsetting communications, misdirecting troops, spreading panic. Scorzani listened, understanding immediately the implications under international law. The Hague Convention of 1907 was clear.

Soldiers captured while wearing enemy uniforms forfeited their rights as prisoners of war and could be executed as spies. This possibility caused extensive discussion with General Our Alfred Yodel and Field Marshal Ger Fon Runstead. Hitler assured Scotsy that the tactic was legitimate as long as his men removed the Allied uniforms before engaging in actual combat. Within days, Scorzani submitted his plans to Yodel.

He requested 3,300 men with knowledge of English and American dialect. On October 25th, the Ober commando dem issued an order to every headquarters on the Western Front requesting English-speaking volunteers for secret commando operations. The order signed by Field Marshall Wilhelm Kitle himself requested soldiers with fluency in English language and knowledge of American idiom. Scotsy knew this broadcast request would reach Allied intelligence within days.

He sought permission to cancel the entire operation, but Hitler denied the request. The Allies indeed intercepted the order on November 30th, but intelligence officers dismissed it as a deception, unable to believe the Germans would be so brazen.

Volunteers arrived from all branches of the German military, most having no idea what they had signed up for. Fritz Priest, a 21-year-old Luftvafa private trained as an English translator, thought he would interrogate American prisoners far from combat. Instead, he found himself isolated behind barbed wire at the training camp established at Graphenvir in eastern Bavaria. Security was extreme. One man was shot when his letter home contained too much detail.

The volunteers discovered their mission only after arrival. The reality of what Scotsy had to work with would have been comical if the stakes were not so high. Of the 2500 men eventually assembled, only 10 spoke perfect English with knowledge of American idioms. Another 30 to 40 spoke English well, but had no understanding of American slang.

Between 120 and 150 spoke English moderately well. The remainder had only school level English, barely able to say more than yes or no. Scorzani later wrote that after a couple of weeks, the result was terrifying. Those with minimal English were instructed to exclaim, “Sorry,” if approached by Americans, then open their trousers and hurry off, figning diarrhea.

The equipment situation proved equally desperate. OB West was asked to procure 15 Sherman tanks, 20 armored cars, 20 self-propelled guns, 100 jeeps, 40 motorcycles, one 120 trucks, and sufficient British and American uniforms. The delivery fell catastrophically short of requirements.

Only two Sherman tanks arrived, both in poor condition, with one breaking down almost immediately. Instead of the requested American armor, Scorzani received five Panther tanks, six armored cars, six armored personnel carriers, and five Sturtormutz assault guns, all German.

The Panthers were disguised with sheet metal cladding, olive drab paint, and white star insignia. Scorzani himself admitted they would fool only very young American troops seeing them from very far away at night. The uniform situation was worse. Many were British, Polish, or Russian uniforms. Some were summer issued despite the December offensive date. Others bore blood stains or P markings.

Units across Germany, confused by the request, sent whatever they could find. The brigade was flooded with Polish and Russian equipment from units that had no understanding of the operation’s purpose. Scorzani managed to acquire enough authentic American uniforms and weapons for only the commando teams. The best English speakers were formed into a special unit designated Einheil, named after SS Captain Ernstelo, who would lead them.

These teams received intensive training despite the compressed timeline. They studied the organization of the American army, learning badges of rank, military customs, and drill procedures. Some were sent to P camps at Kustrin and Lindberg to practice their English with captured American soldiers.

They watched American movies to perfect accents and learn current slang. They memorized American brand names, sports teams, popular songs, and Hollywood stars. The commandos practiced walking like Americans, smoking like Americans, even chewing gum like Americans. The missions were divided into three categories. Demolition squads of five to six men would destroy bridges, ammunition dumps, and fuel stores.

Reconnaissance patrols of three to four men would scout both sides of the Muse River, passing on false orders to American units they encountered, reversing road signs, removing minefield warnings, and cordoning off roads with warnings of non-existent mines. Lead commando units would work with attacking German forces, cutting telephone wires, destroying radio stations, and issuing false orders. The commandos knew the risks.

If captured in American uniform, execution was virtually certain. But there was another danger. In the chaos of battle, they might be shot by their own side if German troops mistook them for actual Americans. For identification, they would use specific signals. Vehicles would display a small yellow triangle. Tanks would maintain specific gun positions. Soldiers would wear colored scarves beneath their uniforms.

On December 14th, Panza Brigade 150 assembled near Badminster Eiffel. On the afternoon of December 16th, they moved out, advancing behind three attacking Panza divisions. The plan called for Scorzan’s disguised forces to move around the spearhead divisions once they reached the high fence, then race ahead to capture the Muse bridges.

The operation depended entirely on the rapid advance of the first SS Panza division commanded by Yakim Piper. If Piper’s armored spearhead broke through quickly, Scorzeni’s disguised troops could slip through in the confusion and reach the bridges before American engineers destroyed them. December 16th, 1944 began before dawn.

Through the dark forests of the Arden, more than 200,000 German troops launched Hitler’s last great offensive in the West. The initial assault achieved complete surprise. American forces, thinly spread across an 80-mile front, faced overwhelming numbers. Four inexperienced or battleweary American divisions confronted 30 German divisions supported by nearly 1,000 tanks.

The German artillery barrage shattered the frozen morning. Search lights bounced off low clouds to illuminate the battlefield. Infantry advanced through the snow-covered forests. Panzas rumbled forward on narrow roads. For the first hours, everything proceeded according to plan.

The Einhalla teams infiltrated in the confusion. Dressed in American uniforms, driving captured jeeps. They slipped through the chaos of the American withdrawal. One team drove directly into an American-held town, scouted all defenses, then on their way out redirected an American convoy of armor and supplies to the wrong road.

Two other teams successfully misdirected Allied convoys, adding to the general confusion. They cut telephone wires, removed road signs, spread false rumors of German breakthrough deeper than actual penetrations. But on December 17th, reality destroyed the operation’s prospects. The first SS Panza division failed to reach its objectives on schedule.

Fierce American resistance at Elenborn Ridge denied the Germans the northern roads they needed. At St. Vith American defenders fought ferociously, delaying the German timetable by nearly a week. The rapid breakthrough that Operation Grife required never materialized. Scorzani realized that same day that his mission’s original aims were doomed.

He attended a staff conference at Sixth Panza Army headquarters and suggested his brigade be used as a conventional unit. The request was approved. Panza Brigade 150 was ordered to assemble south of Malmi and report to the first SS Panza division, but the commando teams were already behind American lines. Some successfully completed their missions.

Others were captured when they failed password challenges, when nervous American soldiers noticed British weapons or German boots, when their English failed under pressure, when they could not answer simple questions about American culture. The capture near Ivi on December 17th of Peris, Billing and Schmidt created the panic that would define the operation’s real impact.

During interrogation, Schmidt made a statement that electrified Allied intelligence. He claimed their mission was part of a larger operation to infiltrate Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force and capture or kill General Dwight Eisenhower himself. Whether Schmidt believed this rumor or was spreading deliberate disinformation remains unclear.

No evidence has ever confirmed such a plan existed. The actual mission was to capture bridges over the Muse River. But the statement had immediate consequences. Within hours, security around Eisenhower was dramatically increased. The Supreme Commander found himself virtually imprisoned in his headquarters at Versailles, surrounded by guards who checked everyone entering the building.

Eisenhower was reportedly furious at the confinement, especially when it extended through Christmas. After several days, he angrily declared he had to get out and didn’t care if anyone tried to kill him. But the paranoia spread far beyond protecting Eisenhower.

Allied forces already reeling from the German offensive now saw potential infiltrators everywhere. Checkpoints appeared throughout the Allied rear areas, greatly slowing the movement of troops and supplies. American military policemen began interrogating every soldier passing through using questions designed to identify Germans posing as Americans. What is the capital of Illinois? Who won the World Series in 1940? Who is Mickey Mouse’s girlfriend? What team plays at Wrigley Field? Who is married to Betty Greybel? Where does the guard stand in a football formation? Who is Frank Sinatra? What is the name of

the president’s dog? The questions ranged from state geography to baseball statistics to Hollywood gossip to American slang. MPs improvised constantly, creating new questions based on whatever American trivia they could think of. The system was chaotic and often absurd. Many genuine American soldiers could not answer the questions.

Regional differences meant soldiers from one part of America had no knowledge of details from other regions. Educational differences meant some Americans never learned state capitals or followed baseball. The checkpoints created numerous problems.

General Omar Bradley was detained when he correctly identified Springfield as the capital of Illinois. But the MP believed it was Chicago and held him until his identity could be verified. Brigadier General Bruce Clark was held at gunpoint after incorrectly stating the Chicago Cubs played in the American League. A captain spent a week in detention after being caught wearing German boots he had taken as souvenirs.

British soldiers faced particular difficulties. When reconnaissance officer David Nan encountered a guard demanding to know who won the 1940 World Series, he could only reply he hadn’t the faintest idea. British troops who could not answer questions about American sports or geography were detained until their identities could be verified through other means.

Some American soldiers gave deliberately wrong answers to protest the absurd interrogations, resulting in their own detention. Others became angry at being questioned by junior enlisted men, creating confrontations that further slowed movement. The paranoia affected military operations significantly.

Troop movements that should have taken hours required days as every vehicle was stopped and every occupant questioned. Supply convoys sat idle at checkpoints while drivers attempted to prove their American identity. Units rushing to reinforce threatened sectors were delayed by repeated interrogations. Commanders found their orders questioned by subordinates who suspected everyone might be a German infiltrator. The psychological impact on German infiltrators was severe.

Those still behind American lines found themselves unable to move freely. The cultural questions exposed their preparations inadequacies. They had studied military procedures, learned rank insignia, memorized American army organization, but they had not anticipated interrogations about baseball statistics or Hollywood marriages or regional slang.

Some infiltrators attempted to avoid checkpoints entirely, traveling cross country or through forests. This made them more conspicuous to American patrols. Others tried to bluff through checkpoints, offering excuses for why they could not answer questions. Few succeeded. Between December 16th and December 31st, American forces captured 23 members of Operation Grife.

16 were captured in December 1944. The team leader, Ga Schultz, was captured later and tried in May 1945. Each captured infiltrator faced military trial. The legal situation was clear under international law. Article 23 of the Hague Convention concerning land warfare specifically forbade improper use of enemy military insignia and uniform.

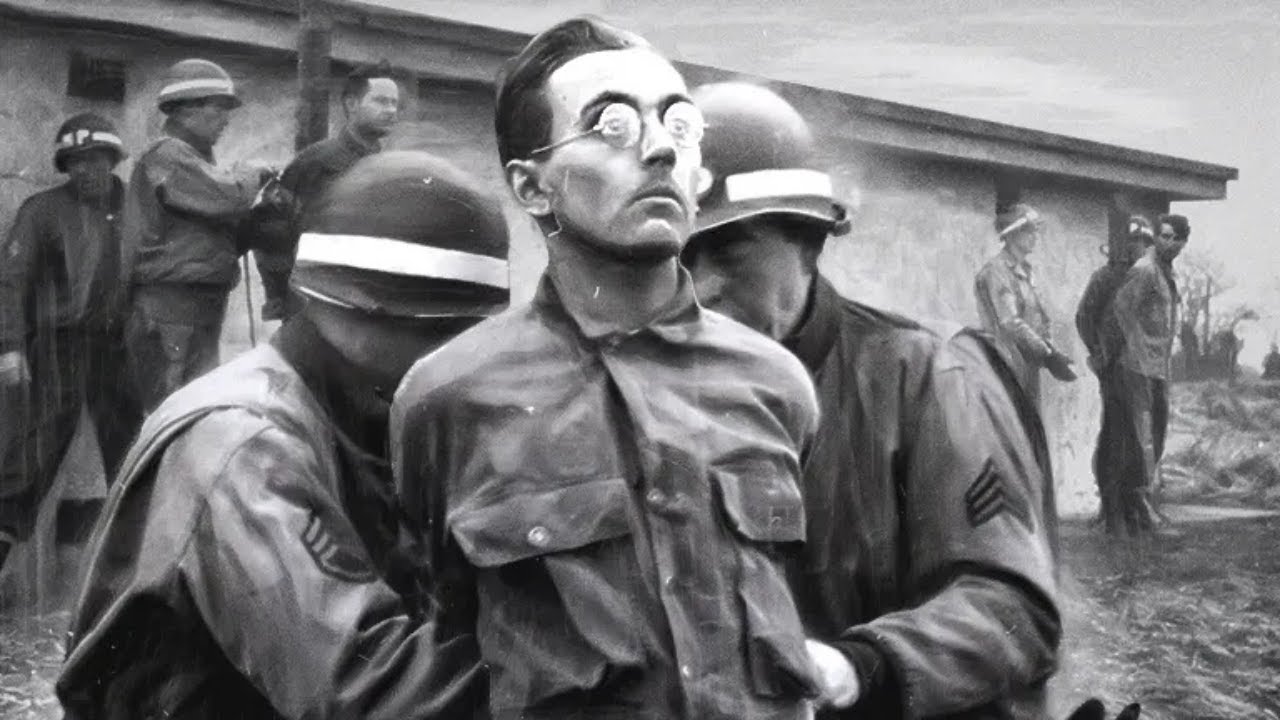

Soldiers captured wearing enemy uniforms while conducting military operations could be tried as spies rather than treated as prisoners of war. The first trial began at Hungri Chappelle on December 21st. Pernas, Billing, and Schmidt faced charges of violating the laws of war by wearing American uniforms while conducting military operations. The evidence was overwhelming. They had been captured in American uniforms with American weapons, carrying American identification, but wearing German field gray underneath. The trial was swift.

All three were convicted and sentenced to death by firing squad. On December 23rd, 1944, 2 days before Christmas, the sentences were carried out. American military police led the three Germans to the execution site. Captain J. Iser of the 633rd Medical Clearing Station pinned white paper targets over their hearts. Schmidt’s glasses were removed.

The prisoners were blindfolded. Military police formed the firing squad. Billing shouted, “Long live our furer Adolf Hitler.” At the moment of execution, the rifles fired. All three men died instantly. Their bodies were cut down, carried away, and buried.

Eventually, they would be interred at the German military cemetery at Loml, Belgium, where they rest today alongside more than 39,000 other German war dead. 13 additional operation grife participants were tried and executed at either Henry Chappelle or Hui between December 21st and December 31st. Wilhelm Visenfeld, Manfred Bronny, Hans Reich, Arno Krower, Gunter Schultz, Hehart Meagel, Host Gerik, Norbert Pollock, Ralph Benjamin Meer, Hans Vitzuk, Ottoa, Alfred France, and Anton Moruk all faced firing squads. Each execution followed military trial.

Each trial found the defendants guilty of violating the HEG convention. Each sentence was reviewed and approved by senior commanders. The executions were carried out with military precision without malice but without mercy. Team leader Ga Schultz was tried by military commission in May 1945 and executed near Branch on June 14th.

Why his trial was delayed until after Germany’s surrender remains unclear. Who ordered his execution carried out also remains uncertain. The United States 9th Army carried out the sentence. In total, 17 Operation Griff participants were executed for wearing enemy uniforms. The operation’s tactical accomplishments were minimal. No bridges were captured. No major demolitions succeeded.

No critical communications were permanently disrupted. A few road signs were reversed. Some telephone lines were cut. Several American units received false orders, though most were quickly corrected. But the psychological impact vastly exceeded any tactical results. For weeks, American forces operated under the assumption that German infiltrators might be anywhere.

The paranoia affected decision-making at every level. Eisenhower’s confinement meant the Supreme Commander was isolated from direct observation of battlefield conditions during the critical opening phase of the offensive. The checkpoint delays slowed the American response to the German penetration. Units that should have reached threatened sectors in hours took days to arrive.

The widespread suspicion degraded unit cohesion. American soldiers who should have been focused on fighting Germans to their front instead worried about possible Germans among them. The Battle of the Bulge itself proceeded independent of Operation Grafe’s failure.

German forces drove deep into American lines, creating the bulge that gave the battle its name. At Bastonia, American defenders held out despite being surrounded. On December 22nd, when German officers delivered a surrender ultimatum, acting commander, Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe, responded with a single typed word that became legendary to the German commander, nuts, the American commander.

When the confused German officers asked what it meant, they were told it was the same as go to hell. The 101st Airborne held Bastonia until relieved by Lieutenant General George Patton’s Third Army on December 26th. Patton’s forces had executed a remarkable 90° turn, driving north to break the siege. By early January, Allied counterattacks had eliminated the bulge and restored the front lines.

The battle lasted from December 16th, 1944 to January 25th, 1945. More than 1 million men participated, making it the largest battle fought by the United States Army outside the Civil War. American casualties exceeded 80,000, including 19,000 killed and 23,000 captured. German casualties were similar, but Germany could not replace those losses.

The battle marked the end of Germany’s ability to conduct offensive operations in the west. Hitler had gambled everything on the Arden’s offensive and lost. For Otto Scorzeni, Operation Grife was over by December 17th when Panza Brigade 150 converted to conventional operations.

On December 21st, the brigade attempted to capture Malmi but was repulsed after several assaults. Scorzini was wounded by artillery shrapnel near Lineville. He recovered and continued serving until Germany’s surrender. In May 1945, Scorzini surrendered to the 30th Infantry Regiment. He spent 2 years in custody, awaiting trial. At the DHA trials in 1947, Scorzani and nine officers of Panza Brigade 150 faced charges of improperly using American uniforms by entering combat disguised and treacherously firing upon American forces. They were also charged with wrongfully obtaining American uniforms and Red Cross parcels from P camps.

Scorsese’s defense rested on a crucial distinction. His men had been ordered to remove American uniforms before engaging in actual combat. The disguises were for infiltration and deception, not for fighting. A surprise defense witness proved decisive. FF Yo Thomas, a former British special operations executive agent, testified that Allied forces had used identical tactics.

He had personally worn German uniforms behind enemy lines during missions in France. The military tribunal drew a clear distinction between using enemy uniforms during combat and using them for deception. It could not be proven that Scorseni had ordered his men to fight while wearing American uniforms. The tribunal acquitted all defendants. The verdict was controversial.

17 of Scorzan’s men had been executed for the same actions for which he was acquitted. The difference appeared to be timing and evidence. The men executed in December 1944 had been captured in American uniforms. Scorsani tried in 1947 could demonstrate his orders prohibited combat while disguised.

The trial established important precedence regarding the laws of war. Using enemy uniforms for deception was ruled a legitimate ruse deare provided combatants removed the disguises before engaging in combat. This distinction would influence interpretation of international law for decades. Scorzan did not remain in custody long. In 1948, he escaped from an internment camp in Dharmmstad.

Former SS officers disguised as American military police facilitated his escape. Some historians speculate American intelligence may have tacitly allowed or even assisted the escape, though no evidence confirms this. Scorzeni spent time hiding on a Bavarian farm, then in Saltsburg and Paris, eventually settling in Spain.

He worked as a military adviser to Egyptian President Gaml Abdel Nasa. Scotseni died of cancer on July 5th, 1975 in Madrid at age 67. He never expressed regret for Operation Grief or any other wartime actions. The checkpoint interrogations became part of American military folklore.

The questions about baseball and Hollywood, state capitals, and movie stars became symbols of how cultural identity served as a security tool during the crisis. The improvised system, however chaotic, proved effective at exposing infiltrators whose language training could not replicate the casual cultural knowledge that Americans absorbed naturally from childhood.

Being American involved more than speaking English or wearing the right uniform. It involved shared cultural experiences, common references, collective memories that could not be adequately taught to foreigners in weeks of training. This cultural cohesion often taken for granted proved to be a national security asset when tested by enemy infiltrators.

The 17 men executed for Operation Grafe are remembered today primarily through military cemeteries and historical accounts. Their graves at Loml are maintained with the same care as those of soldiers who died in conventional combat. The cemetery makes no distinction between those executed as spies and those killed in battle. All are German war dead.

Manfred Perus was 23 years old at execution. Gunther Billing, 21, remained a convinced Nazi to his final moment. Wilhelm Schmidt, 24, faced death with quiet resignation. Each was someone’s son, perhaps someone’s brother. Each had made choices that led to that frozen morning in Belgium, to those posts, to those blindfolds, to those rifles.

Operation Grafe’s legacy extended beyond its tactical failure. The operation demonstrated that special operations cannot compensate for conventional military failure. Scores infiltrators could not capture bridges if Piper’s panzas never reached them.

No amount of deception and confusion could substitute for the breakthrough that never occurred. Yet the operation succeeded in creating disruption far exceeding what the actual infiltrators accomplished. The mere possibility of infiltration created panic affecting hundreds of thousands of soldiers. This gap between perception and reality became a key lesson in modern strategic thinking about psychological warfare.

The Battle of the Bulge ended in late January 1945. Allied forces resumed their advance toward Germany. Within 4 months, the Third Reich collapsed. Hitler committed suicide in his Berlin bunker. Germany surrendered unconditionally on May 8th, 1945. The 17 executed Operation Grafe participants were already in their graves. Their war ended violently on Belgian soil far from home.

Their operation had failed in its tactical objectives, but succeeded in creating confusion and fear that hampered Allied operations during the critical opening phase of the battle. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill speaking to Parliament on January 18th, 1945, while the battle still raged, declared it undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war, and will, I believe, be regarded as an ever famous American victory.

Churchill explicitly noted that Americans had engaged 30 to 40 men for every British soldier engaged, emphasizing that this was fundamentally an American battle and an American victory. The checkpoint guards who asked about baseball did not know they were creating folklore. They were solving an immediate problem, improvising security measures to identify potential enemies.

Their solution worked because it was rooted in genuine shared culture. Americans knew about baseball and Hollywood and state capitals because they grew up American, absorbing that knowledge naturally. Germans trying to impersonate Americans could study facts but could not replicate that natural cultural fluency.

This distinction between learned facts and absorbed culture proved decisive. The German failure demonstrated a principle that remains relevant. Cultural knowledge absorbed through lived experience over years cannot be quickly taught to adults from different backgrounds. Modern special operations forces have learned from Operation Grafe’s mixed results.

Intelligence services now spend years preparing deep cover agents precisely because cultural fluency cannot be quickly taught. Language training, factual knowledge, and behavioral coaching are necessary but insufficient. Genuine cultural fluency requires immersion and time. The fundamental challenge persists across decades.

Culture is absorbed through experience, not taught in classrooms. Operation Grafe demonstrated both the potential and the limits of special operations. Small units conducting unconventional operations can create disruption far beyond their numbers. The psychological impact can exceed tactical results by orders of magnitude.

But without conventional military success providing the necessary conditions, special operations cannot achieve strategic objectives. Deception cannot substitute for victory. For historians and military strategists, Operation Grife remains a compelling case study. It exemplifies how ambitious planning disconnected from realistic assessment of capabilities leads to failure.

Hitler’s late war decision-making followed this pattern. Grandiose in conception, inadequate in resources, divorced from operational reality. Yet the operation’s unintended success in creating panic validated the concept that psychological warfare and deception can be force multipliers.

The 17 men who died before firing squads for wearing enemy uniforms would be largely forgotten if not for the historical record that preserves their stories. They were not particularly important men. They accomplished little before their capture. Their operation failed comprehensively.

Yet their executions marked an important moment in military and legal history, clarifying the application of international law regarding the use of enemy uniforms in warfare. The legacy lives in the lessons their operation taught. Identity verification remains crucial for security. Cultural knowledge remains difficult for outsiders to fake quickly. Special operations remain valuable but cannot substitute for conventional military success.

The laws of war remain important but subject to interpretation based on circumstances and evidence. The human cost of war extends beyond those killed in combat to include those executed after capture for violations of the laws of war. Each execution was a human being with family and history and potential ended by bullets fired on legal authority after proper trial.

The graves at Loml Mark lives cut short by war and its brutal logic. The checkpoint guards who asked about baseball were American soldiers who followed orders and carried psychological burdens from executing prisoners, even enemies convicted of espionage. Operation Grief failed to capture a single bridge. It caused no major destruction.

It killed relatively few Americans directly, but the fear it created delayed reinforcements, disrupted command decisions, and consumed resources during critical days. The indirect impact, impossible to quantify precisely, shaped the battle’s opening phase. The infiltrators being caught, tried, and executed within days, demonstrated American military justice operating under wartime pressure.

The speed from capture to execution reflected combat conditions and established precedent, though modern standards would require more deliberate proceedings. The Battle of the Bulge grounded on for five more weeks after the infiltrators were executed, ultimately resulting in German defeat and the elimination of Germany’s strategic reserve. The story of Operation Grife and the Battle of the Bulge reminds us that warfare encompasses more than battlefield operations.

Psychological impact, cultural factors, and perception often matter as much as tactical results. A failed operation that creates panic may achieve more strategic disruption than a successful operation that remains undetected. The checkpoint interrogations, absurd as they sometimes seemed, worked because they tested knowledge that genuine Americans possessed naturally, while infiltrators could not replicate despite training.

The American soldiers who fought in the Battle of the Bulge faced not only a powerful enemy offensive, but also the psychological burden of suspecting that enemies might be anywhere, wearing any uniform, speaking any language. This erosion of certainty marked a new dimension in warfare that would influence military operations and security procedures for generations to come.