No one who lived through May 8th and 9th of 1945 forgot what those days felt like. The war that had consumed an entire generation officially ended for Germany on the evening of May 8th when the act of unconditional surrender came into force at 2301 central European time. But if anyone expected the next morning to bring silence, clarity or peace, they were wrong.

The first day after the war ended was not a day of celebration. It was a moment of suspended reality. An entire country caught between collapse and survival, between guilt and relief, between ruins and the first faint idea of a future. And this is the story of that day. Imagine waking up to a world where the government no longer exists.

The army has disintegrated. The police have vanished and the nation you lived in yesterday has ceased to function overnight. That was Germany on the first day after World War II. A modern industrial society had collapsed into something closer to a giant refugee camp spread across a landscape of smoking ruins.

For millions, the morning of May 9th, 1945, began with no clear sense of what had happened. Most Germans didn’t have radios anymore. Many were destroyed by bombings. Others confiscated or silenced in the last days of the Reich. Newspapers weren’t printing. Trains weren’t running. Telephone lines were cut. Rumors traveled faster than facts.

Some people had heard about the surrender through word of mouth from soldiers. Others saw it on notices the allies had posted during the night. Many simply stepped outside and realized the shooting had stopped. The silence was the first strange thing people noticed. After years of air raid sirens, artillery fire, collapsing buildings, and the constant drone of aircraft, the quiet sounded unnatural, almost threatening.

Cities that had once held hundreds of thousands of people now resembled enormous graveyards of stone and twisted steel. Berlin, Hamburgg, Dresden, Cologne, Munich, Frankfurt. All of them looked like they had been erased and crudely sketched back in with rubble. In Berlin, where the fighting had ended just a week earlier, entire districts were nothing but burnt out shells.

The few surviving apartments were overcrowded with families, refugees, and wounded soldiers. People slept on broken furniture in stairwells in cellars still blackened by smoke. Water pumps were damaged, electricity was unreliable, and the smell of fire lingered everywhere because ruins continued to smolder long after the battle ended.

On that first day after the war, 20 million Germans were on the move, fleeing Soviet forces, searching for lost family members, or wandering from one town to another in hope of finding food or shelter. The roadways were filled with endless streams of people pushing carts, bicycles without tires, baby carriages filled not with children, but with pots, blankets, and whatever scraps of life they had managed to save.

Many of them had walked for weeks. Some had walked for months. Hunger was immediate. Food distribution had collapsed completely. In some places, people ate only what they could salvage from abandoned army depots or destroyed homes. Others traded jewelry, clothing or tools for a handful of flour or a few potatoes. Children dug through ruins looking for anything edible, burnt grain, old canned goods, even animal feed.

No one knew when the Allied authorities would organize supplies, and many feared starvation more than anything else. For German soldiers, the first day after the war was a mixture of humiliation, relief, and fear. Most had discarded their uniforms to avoid being arrested. Some walked home in civilian clothes they had stolen or traded for.

Others stumbled along the roads still wearing torn military boots with makeshift bandages wrapped around shrapnel wounds. Surrender meant survival, but it also meant uncertainty. Many worried about being taken to P camps. Those captured by the Soviets expected harsh treatment, and in many cases their fears were justified.

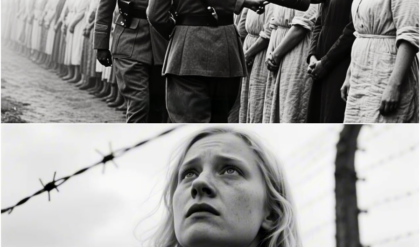

Others surrendered to American or British forces, hoping for better conditions. Across Germany, the Allies were not yet administrators. They were an occupying force that had just defeated a brutal enemy. Soldiers patrolled streets with weapons ready. Curfews were imposed. Armed checkpoints appeared at every major intersection.

In some cities, German civilians were ordered to bury the dead, still lying in the streets or to clear the rubble. The Allies were overwhelmed by the scale of destruction and the number of displaced people. They were not prepared to instantly create order. The psychological atmosphere on that day is almost impossible to summarize.

There was no single emotion shared by everyone. Instead, there was a fragmented landscape of feelings. Some Germans felt deep shame as they saw the consequences of Nazi rule. Others felt anger and denial, refusing to believe the war was truly lost. Many felt only exhaustion, a level of fatigue so total that people could barely think beyond the next hour.

And some, especially young people who had grown up knowing nothing but Nazi propaganda and war, felt something unexpected. Relief that the nightmare was finally over. But the most pervasive emotion was uncertainty. No one knew what the Allies plan to do with Germany. Would the country be dissolved? Would people be punished collectively? Would food and supplies ever return? Would families be reunited? Entire communities asked these questions all at once, but no one had answers.

Life on the first day after the war wasn’t about rebuilding. It wasn’t about politics. It wasn’t about guilt or ideology. It was about basic survival, water, shelter, safety, food, and the hope that tomorrow might be a little less chaotic. And yet, even in that first day, tiny signs of a different future began to appear.

Allied troops handed out chocolate and chewing gum to children. German civilians approached soldiers cautiously, no longer as enemies, but as the only authority left. In some towns, church bells rang for the first time in years, not to warn of air raids, but to signal that the war was over.

A few people dared to talk openly again without fear of the Gestapo. Others wrote messages on pieces of wood or old bed sheets. We are alive, looking for family, food needed, children safe here. The Reich had fallen, but life in Germany had not ended. It was beginning again slowly, painfully, and with no guarantees.

As the sun rose higher on that first full day of peace, one of the strangest and most unforgettable sites in Germany was the sudden presence of Allied soldiers walking openly through streets that had once been controlled by Nazi troops and propaganda posters. For years, the image of the Allied armies had been presented to Germans as monstrous, cruel, almost inhuman forces.

And yet, when real Allied soldiers appeared, many civilians were surprised to see young men barely older than their own sons, tired from months of fighting, cautious, but not hostile, and often just as confused about what came next. In the American and British zones, encounters between soldiers and civilians were often tense, but not violent.

Civilians were required to approach with hands visible, not make sudden movements, and obey strict curfews. But there were moments, small human moments, that stood out. An American soldier giving a thirsty old man his canteen. A British sergeant helping a woman lift a fallen beam so she could enter what remained of her home.

These gestures didn’t erase the suffering of the war, but they made the end of it feel real. In the Soviet zone, the situation was far more complicated. The Red Army had suffered unimaginable losses. over 20 million dead, and many soldiers carried a deep desire for revenge. Violence, assaults, and looting were widespread in the first days and weeks after the war.

German civilians feared the Soviet troops more than anything else, and families hid women and young girls in sellers or behind false walls. Even so, not every encounter was hostile. There were cases of Soviet officers protecting civilians, organizing food distribution, preventing chaos when they could. But the fear in the eastern part of Germany was among the defining emotions of that first day and the weeks that followed.

Across the country, the German police had vanished. In many towns, there was suddenly no authority except the local mayor, if he was still alive or had not fled. Some communities set up informal patrols to prevent looting. Others simply left everything to chance. But without a functioning government, currency quickly lost meaning.

People bargained with cigarettes, coffee, sugar, or whatever small valuables they had left. A single American cigarette could buy a meal. A few chocolate bars could buy several pieces of clothing. Bartering became the only economy functioning on that first day. And then there was the question of identity.

Without a government, without the swastikas that had dominated public buildings for 12 years, without Hitler’s voice on the radio, many Germans felt as if something enormous had been ripped out of their lives. Even those who despised the Nazi regime were unsure what came next. The psychological collapse of an entire national ideology created a vacuum that was almost as frightening as the physical destruction around them.

In some places, Germans tore down Nazi symbols themselves. banners, posters, portraits, signs. In others, Allied soldiers forced civilians to remove them. There are documented cases where entire crowds were ordered to march past piles of corpses in concentration camps so they would see what their government had done. On the first day after the war, the Allies began the process of confronting Germany with the reality of the Holocaust.

This was not yet organized dennazification that would come later, but the raw exposure to the consequences of the regime. For civilians, this experience was shocking, confusing, and often met with disbelief or denial. Many Germans claimed they had known nothing about the camps. Others admitted they had heard rumors, but dismissed them.

The truth, of course, varied from person to person, town to town. But the first day after the war marked the beginning of a new relationship between Germans and the events of the previous 12 years, one that would take decades to fully explore. Meanwhile, hunger continued to shape every decision. Women lined up in long cues outside bakeries, hoping flour would be available.

In many towns, there were no shops left intact, so people gathered at makeshift distribution points where Allied trucks occasionally brought supplies. The average daily calorie intake for many Germans in 1945 was around 1,000 calories, barely enough to survive. On that first day, most people survived on even less. They boiled nettles, collected dandelion leaves, cooked thin soups from whatever vegetables they could find.

In some cases, people used the last remains of furniture as firewood. Pots were placed on bricks heated by burning wood pulled directly from collapsed houses. But even in the middle of all this suffering, there were unexpected moments of hope. Children who had grown up knowing nothing but sirens and bomb shelters explored the ruins with a strange sense of adventure.

They found pieces of burned toys, shards of colored glass, metal fragments shaped like strange treasures. They played among the stones, even though the danger of unexloded bombs was everywhere. For them, the silence of the first day after the war felt almost magical. No more running to shelters. No more hiding from the sky. For adults, hope came in different forms.

Some were reunited with family members who had disappeared during the fighting. Others found neighbors alive whom they had assumed dead. Letters began to circulate, crumpled bits of paper passed from hand to hand, carried by travelers, delivered by anyone who could cross the ruined roads. The words, “I am alive,” were the most precious message anyone could receive.

Small markets began to appear in open spaces where buildings had been destroyed. People laid out blankets and traded whatever they had. A woman might offer a winter coat in exchange for a few onions. A former soldier might offer a pair of boots for a loaf of bread. No one cared about law or official currency.

Survival created its own rules. As the first day progressed, the atmosphere of uncertainty deepened. Many Germans expected mass arrests. Some hid their photographs, uniforms, documents, anything that might connect them to the Nazi party. Others burned papers in their backyards, creating small clouds of ash that floated over the ruins.

There was a genuine fear that the allies might execute anyone associated with the regime. While the mass executions never happened, fear defined the actions of thousands on that day. And yet, despite all the fear and confusion, despite the hunger and destruction, despite the collapse of every institution that made life predictable, there was one truth that every German understood.

By the evening of May 9th, 1945, the war was finally over. It almost didn’t feel real. For years, the Nazi government had promised victory, even as defeat became obvious. Joseph Gerbal’s propaganda insisted that new wonder weapons would turn the tide. Hitler had demanded total loyalty until the last minute.

And then suddenly all of it vanished into the silence. The first day after the war was not peaceful, not joyful, not even hopeful in any traditional sense. But it was the first day in 12 years that Germans could imagine a future without Hitler. It was the first day children fell asleep without the fear of bombers overhead.

It was the first day women could walk outside without checking the sky. It was the first day the world began to shift from destruction toward rebuilding. But rebuilding would take years, years of shortages, occupation, political tension, guilt, fear, and immense effort. On that first day, no one could imagine how Germany would look in 1955 or 1975 or 1990.

The future was a blank page written in pencil, smudged by uncertainty. Yet in that blankness, something fragile but essential began to grow. The idea that life could continue, that survival was possible, and that peace, however fragile, had returned. As night approached on that first day after the war ended, Germany entered a darkness that felt heavier than any blackout imposed during the conflict.

During the war, darkness had been a command, a preparation for enemy bombers. Now it was simply the absence of power, the absence of structure, the absence of a functioning nation. Whole cities lay in complete shadow except for a few candles flickering in broken windows or the distant glow of allied campfires on the edges of urban ruins.

Inside homes, those few that still had walls and roofs, families gathered quietly, speaking in low voices. People tried to process everything they had witnessed that day, but the shock was still too raw. Children asked questions their parents couldn’t answer. What happens now? Where do we get food? When will the soldiers go home? Adults asked themselves even harder questions about the past 12 years.

What they had believed, what they had ignored, what they had done or failed to do. But on that first night, most people didn’t want philosophy. They wanted safety. They wanted to close their eyes and hope that tomorrow wouldn’t bring more chaos. In rural areas, the atmosphere was somewhat different. Many villages had escaped the full destruction that cities suffered, and the first day after the war brought an eerie sense of calm.

Farmers inspected their fields, knowing they would soon be pressured to produce food, not only for themselves, but for entire regions on the brink of starvation. Livestock had been lost or slaughtered during the final months of fighting. But in the countryside, at least the land itself remained. For many Germans, rural communities became temporary sanctuaries, places where people fled from devastated cities to look for relatives, food, or simply a few days of safety.

But even in villages, fear persisted. Soviet soldiers passed through rural roads in large numbers, and rumors spread rapidly, some true, many exaggerated about violence, confiscations, and revenge. Mothers hid their daughters. Families locked their doors at night, something that had been rare in rural Germany before the war.

And in the western zones, villagers listened carefully for the sound of Allied vehicles approaching, unsure whether the soldiers would bring discipline or demands. In the hours after sunset, another transformation occurred. German citizens began to realize the full extent of their isolation. For years, they had been told that Germany was strong, powerful, protected by its armies and its leaders.

Now they understood with painful clarity that the country had been abandoned by its own government long before the war officially ended. Hitler was dead. Gibbles was dead. Himmler had fled. Most Nazi officials had disappeared. The Reich, which had promised a thousand years of order, had survived barely 12. The emotional collapse of the German population on that first day is difficult to describe.

Relief blended with guilt. Shame mixed with fear. Grief overlapped with a faint, fragile sense of hope. Some people cried without knowing exactly why, mourning not only the dead, but the version of themselves that had existed before the war had twisted their lives. Others felt numb, unable to feel anything at all after years of trauma.

But the mood was not entirely bleak. In many towns, people shared what little they had. A neighbor would bring a jar of jam. Another would boil potatoes for a group. Someone else would offer half a loaf of bread. With no functioning money and no government instructions, communities instinctively created their own temporary safety nets, human kindness, worn down but not destroyed by 12 years of dictatorship and 6 years of war, began to reemerge in small but meaningful acts.

Allied forces, despite being exhausted and overwhelmed, also played a crucial role in preventing the situation from descending into absolute chaos. American troops set up field kitchens where possible. British soldiers distributed emergency rations. French units, though stricter and often more suspicious of German civilians, organized basic order in several towns.

Soviet commanders in some regions imposed strict discipline on their forces to stop uncontrolled violence. It was far from perfect, but without Allied organization, the first days after the war could have been even more disastrous. Throughout the night, the skies remained quiet. No air raid sirens, no explosions, just the distant rumble of Allied vehicles and the soft murmur of tens of thousands of people trying to sleep on cold floors in crowded cellers or in makeshift shelters constructed from debris.

For many children, it was the first peaceful night of their lives. For adults, the silence was almost unsettling. As dawn approached on May 10th, the second day of peace, Germany was still a country without a government, without functioning cities, without certainty of survival. But something had changed subtly, deeply, and permanently.

For the first time in years, people awoke not to orders, not to propaganda, not to sirens, but simply to daylight. The war was truly over. In the days and weeks that followed, the shape of postwar Germany slowly emerged. The Allies established administrative zones. Food distribution became more organized. Curfews and regulations brought a form of fragile stability.

Families searched tirelessly for missing relatives. Refugees continued to arrive from the east. The enormity of the Holocaust became unavoidable as Allied forces liberated camps and forced German civilians to confront them. Cities began the slow process of clearing rubble. Some Germans cooperated eagerly, desperate to rebuild.

Others resisted emotionally, unable or unwilling to accept the scale of their nation’s collapse. Reconstruction would take decades. The political transformation of Germany, from dictatorship to democracy, would take generations. But the seed of all those changes was planted on that first day after the war. A day defined not by celebration, but by survival, not by clarity, but by confusion, not by triumph, but by the fragile beginning of peace.

When we look back on May 9th, 1945, it is tempting to see it as the end of tragedy. In reality, it was the beginning of a long, painful, complicated rebirth. The people who lived that day didn’t yet know that their country would rise again, or that Europe would eventually reconcile, or that Germany would one day become a symbol of stability and democracy.

On that morning, all they knew was that the guns had stopped. The bombs had fallen silent and life, broken, shaken, but still alive, had to continue. Germany, on the first day after World War II ended, was a place suspended between destruction and the possibility of renewal. A place where silence replaced bombs.

Where strangers shared the last pieces of bread.