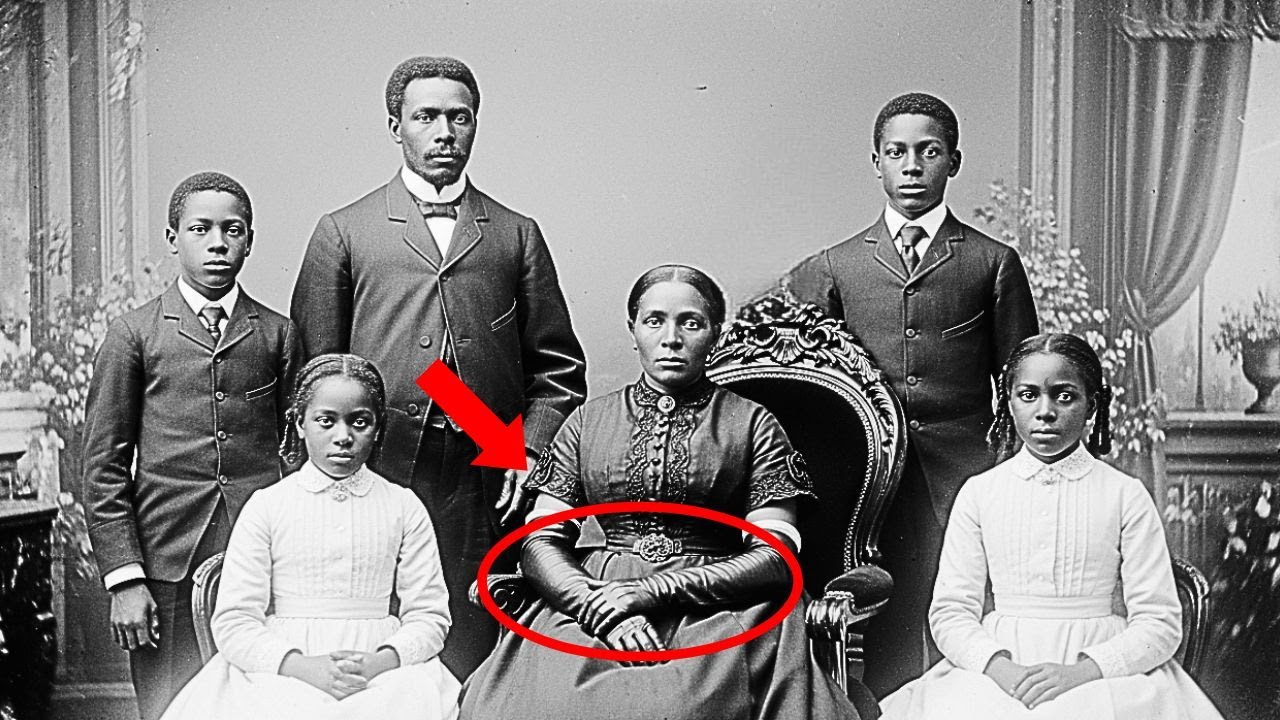

It was just a family portrait, but the woman’s glove hid a horrible secret. Dr. Amelia Richardson carefully unwrapped the tissue paper surrounding the wooden frame, her hands steady despite the anticipation she felt. It was a crisp October morning in 2024, and she stood in her office at the American Legacy Museum in Richmond, Virginia, where she served as senior curator of post Civil War African-American history.

The package had arrived 3 days earlier with no return address, only a brief note. This belonged to my family. I believe it deserves to be seen and understood by more people. Please tell her story. The photograph that emerged from the wrapping was mounted in an ornate Victorian frame with intricate carved details. The image itself was remarkably well preserved for its age. A formal studio portrait from 1875.

According to the photographers’s embossed mark visible in the bottom corner, J Morrison, portrait artist, Richmond VA. The photograph showed a black family of six posed in the elaborate style typical of the era. A distinguished man in his 40s stood at the center, one hand resting on an ornate chair. Beside him sat a woman of similar age.

her posture regal and composed. Around them were arranged four children, two boys and two girls, ranging in age from perhaps 6 to 16, all dressed in fine clothing that spoke of prosperity and care. Amelia had examined hundreds of such photographs during her career.

In the decade following the Civil War and emancipation, black families who had achieved freedom and economic stability often commissioned formal portraits. These images were powerful statements of dignity, success, and humanity. Visual proof that countered the dehumanizing narratives of slavery and the racist propaganda that continued to circulate throughout the country. But something about this particular photograph caught Amelia’s attention immediately.

While the family’s clothing was typical for prosperous African-Americans of the 1870s, the father in a well-tailored suit, the children in clothes that showed both quality and care, the mother’s attire included an unusual detail.

She wore long gloves that extended well past her elbows, nearly to her shoulders, covered by the 3/4 sleeves of her elegant dress. The gloves were made of what appeared to be fine kid leather or silk dyed a dark color that complimemented her dress. In an era when women’s gloves for formal portraits were typically wristlength or at most reached to mid forearm, these struck Amelia as extraordinarily long.

Amelia leaned closer, examining the woman’s face. Her expression was composed and dignified, but there was something in her eyes, a depth of experience, perhaps even sorrow, that seemed to look directly through the camera and across nearly 150 years. The woman’s left hand rested in her lap, the gloved fingers carefully arranged.

Her right hand was positioned on the arm of her chair, the fabric of the gloves smooth and precisely fitted. “Why such long gloves,” Amelia wondered. “Fashion varied, of course, but this seemed deliberately unusual.” She turned the photograph over carefully. On the back, written in faded ink, were the words, “The family, Richmond, Virginia, June 1875. May we never forget.

” Amelia photographed the inscription with her phone, then returned her attention to the image itself. She had a feeling, the kind of instinct developed over years of historical research, that this photograph held a story deeper than what was immediately visible. Amelia spent the remainder of that day attempting to trace the photograph’s origins.

The anonymous sender had provided no contact, and the postmark on the package showed only that it had been mailed from Richmond itself. Without more information about the family’s identity, she would need to rely on the photograph itself and historical records from 1875 Richmond. She began with Jay Morrison, the photographer, whose studio mark appeared on the image.

Amelia accessed the museum’s extensive database of historical businesses and found several references to James Morrison, a Scottish immigrant who had established a photography studio in Richmond in 1867. Morrison’s studio had been located on Broad Street, and it served both white and black clientele, somewhat unusual for the era, as many photographers refused to take portraits of African-Americans or segregated their services.

Morrison’s business records, partially preserved in the Virginia Historical Society archives showed that he had been a successful photographer until his death in 1881. His studio had been known for highquality work and relatively progressive racial attitudes, which explained why a prosperous black family would have chosen him for their portrait. But the records gave Amelia no information about the specific family in the photograph.

Morrison’s appointment books and client lists had been lost to time, possibly destroyed in one of the several fires that had damaged Richmond’s business district in the late 19th century. Amelia turned her attention to the image itself, scanning it at the highest resolution her equipment could achieve.

She imported the digital file into her computer and began examining every detail with specialized software that could enhance contrast, adjust exposure, and reveal details invisible to the naked eye in the original print. As she zoomed in on different sections of the photograph, she began to notice subtle details that raised more questions. The father’s hands, visible and unglloved, showed the calluses and evidence of manual labor.

He was likely a craftsman or tradesman of some kind. The children’s faces showed a mixture of nervousness and pride typical of young people being photographed, an experience that would have been rare and significant for them. But it was the mother’s gloves that continued to draw Amelia’s attention.

As she enhanced the image and adjusted the contrast, she began to see something she hadn’t noticed in her initial examination. The surface of the gloves wasn’t perfectly smooth. There were subtle irregularities, slight bulges and indentations that suggested the gloves were covering something beneath them.

Amelia zoomed in further on the woman’s left arm, where the glove fabric appeared slightly strained near the wrist. The digital enhancement revealed a faint texture beneath the fabric, as if the skin underneath wasn’t smooth, but rather marked or scarred. She moved to examine the right arm and found similar irregularities. The gloves fit well.

They had clearly been carefully chosen or perhaps even customade, but they couldn’t completely conceal the fact that the arms beneath them were not unmarked. Amelia sat back in her chair, her mind racing through possibilities. Burn scars, disease, or something else. Something that would explain why a woman in 1875 would go to such lengths to ensure her arms were completely covered in a formal photograph meant to showcase her family’s success and dignity. She needed expert analysis.

Amelia reached for her phone and called Dr. Marcus Chen, a colleague at Virginia Commonwealth University, who specialized in forensic analysis of historical photographs. Marcus had helped her before with cases where digital enhancement had revealed hidden details in old images. Marcus, I have something I need you to look at, Amelia said when he answered. A photograph from 1875.

There’s something about it that’s bothering me, and I think your expertise might help me understand what I’m seeing. I’m intrigued, Marcus replied. Send me the file, and I’ll take a look this afternoon. Three days later, Marcus arrived at the museum with his portable analysis equipment.

He set up his laptop and specialized scanner in Amelia’s office, carefully positioning the original photograph under controlled lighting conditions. The scanning process would take several hours, capturing the image in segments at a resolution far beyond what standard equipment could achieve. “This is beautiful work,” Marcus commented as he began the initial scan. Morrison was clearly a skilled photographer.

“The composition is excellent, and the exposure is remarkably even considering the technology available in 1875. The long exposure times meant subjects had to remain absolutely still. You can see how carefully everyone is positioned. Amelia nodded, watching as the scanner moved incrementally across the photograph’s surface. What I really want you to focus on are the mother’s gloves.

There’s something about them that seems unusual to me, but I need your technical analysis to confirm what I’m seeing. As the scanning completed and Marcus loaded the highresolution composite file onto his laptop, both researchers leaned in to examine the results.

Marcus opened his forensic imaging software and began applying various filters and enhancements to different sections of the photograph. Let’s start with standard contrast enhancement, he said, adjusting the settings. The image on the screen shifted, details becoming sharper and more defined. He zoomed in on the mother’s face first. She’s beautiful. And look at her expression. There’s such strength there, but also something else.

Sadness, maybe, or perhaps just the weight of experience. He moved down to focus on the gloves, systematically examining first the left arm, then the right. As he applied different filters, infrared analysis, shadow enhancement, texture mapping, patterns began to emerge beneath the fabric of the gloves.

“This is fascinating,” Marcus said quietly, his professional demeanor giving way to visible concern. “Amelia, I think these gloves are covering significant scarring. Look here,” he pointed to the screen where he had isolated the left forearm. “See these linear patterns beneath the fabric, and here, these circular marks near the wrist.

” Amelia felt her stomach tighten as she looked at what Marcus’ analysis was revealing. The patterns were becoming unmistakable. “Those are consistent with restraint injuries,” she said softly. “Shackles, chains,” Marcus nodded grimly and continued his analysis, moving to the upper arms. “And these marks here, these appear to be lash scars.

Multiple incidents healed over time, but leaving permanent tissue damage. He adjusted the settings again, and more details emerged. The scarring is extensive, Amelia. Both arms, from wrists to shoulders, this woman endured sustained repeated trauma.” The two researchers sat in heavy silence, looking at the enhanced images on the screen.

The elegant gloves, which had seemed merely an unusual fashion choice, were revealed as a deliberate concealment, a way to hide the permanent physical evidence of brutality. “She was enslaved,” Amelia said, her voice barely above a whisper. “These are marks from slavery, punishment scars, restraint injuries, the kind inflicted on people who were treated as property rather than human beings.

” Marcus ran additional analyses documenting the extent and pattern of the scarring with scientific precision. His software could approximate the depth and age of scars based on how they affected the surface texture visible even through fabric. Based on the healing patterns I’m seeing, these injuries were sustained over a period of years with the most recent probably occurring at least a decade before this photograph was taken.

So likely before 1865, before emancipation, Amelia pulled up her notes on Richmond’s history during the Civil War and Reconstruction era. Richmond was the capital of the Confederacy. The city had a massive enslaved population and the conditions were often brutal, especially in the final years of the war when resources were scarce and discipline was harsh.

After the war ended in 1865, thousands of formerly enslaved people remained in Richmond or migrated here trying to build new lives. She looked back at the photograph, seeing it now with completely different eyes. This photograph was taken in 1875, 10 years after emancipation. This family had clearly achieved significant success in that decade. They could afford fine clothing, a professional portrait, everything needed to present themselves as prosperous and respectable.

But the mother, she’s carrying the permanent marks of what she survived. Marcus continued documenting his findings, taking detailed screenshots and measurements. The question is, why did she choose to cover the scars so completely? In private, she might have worn long sleeves out of habit or comfort, but this is a formal portrait, a permanent record.

She could have chosen to display the scars as evidence of survival, as many formerly enslaved people did. Instead, she went to great lengths to conceal them. Oh, Amelia knew that to truly understand this photograph and the story it contained, she needed to identify the family. She began a systematic search through Richmond’s historical records from the 1870s, focusing on successful African-American families, who had established themselves in the decade following the Civil War. The task was more challenging than it might have seemed.

While Richmond had a substantial black population in the 1870s, both formerly enslaved people and those who had been free before the war, detailed records of African-American families were often incomplete or non-existent. Many official documents from the era either didn’t record black residents at all or recorded them with minimal information.

Amelia started with property records, reasoning that a family prosperous enough to afford a professional portrait likely owned property. She searched through deed records from 1865 to 1875, looking for black property owners in Richmond. The list was longer than many people would have expected. Despite the enormous obstacles they faced, hundreds of formerly enslaved people had managed to purchase land and homes in the decade after emancipation.

She cross- referenced property ownership with business licenses, looking for craftsmen or tradesmen whose hands might show the evidence of manual labor she had observed in the father’s hands in the photograph. Richmond’s Freedman’s Bureau records, though incomplete, provided some information about formerly enslaved people who had established businesses or trades in the city.

After three days of intensive research, Amelia found a promising lead. Property records showed that in 1871, a man named Daniel Freeman had purchased a modest house on Clay Street in Richmond’s Jackson Ward neighborhood, an area that was becoming the center of black business and cultural life in the city.

Daniel was listed as a carpenter, which matched the evidence of skilled manual labor visible in the photograph. The deed included unusual detail. It listed Daniel’s wife as Clara Freeman and noted four children, Elijah, Ruth, Samuel, and Margaret. The ages of the children matched approximately what Amelia observed in the photograph. But it was another document that convinced Amelia she had found the right family.

In the Richmond Freriedman’s Bureau records, she discovered an entry from 1865, an application for a marriage certificate. Daniel Freeman, described as a colored Freeman who had been free before the war, was applying to legally marry Clara, described only as formerly enslaved, last held by R. Hartwell, Lancaster County.

The application included a detail that made Amelia’s breath catch under distinguishing marks. Someone had written severe scarring on both arms from restraints and punishment. This was the family. Clara Freeman, the woman in the photograph with the long gloves, had been held in slavery in Lancaster County until some point during or after the Civil War.

She had survived brutal treatment that left permanent scars on her arms. After gaining her freedom, she had married Daniel, a free black carpenter, and together they had built a life and family in Richmond. Amelia immediately began searching for more information about Clara’s background.

Lancaster County was in Virginia’s northern neck region, an area known for large tobacco plantations that had relied heavily on enslaved labor. The Hartwell family had been prominent land owners there, though Amelia found little specific information about their treatment of enslaved people. And what she did find was evidence of Clara’s remarkable resilience.

Census records from 1870 showed the Freeman family living in a rented house with Daniel working as a carpenter. By 1875, when the photograph was taken, they had purchased their own home. By 1880, Daniel had established his own carpentry business, and the older children were attending school, a significant achievement for a formerly enslaved family in that era. Amelia knew she needed to find descendants of the Freeman family, people who might have family stories, documents, or information that hadn’t made it into official records.

She posted inquiries on genealogy websites and contacted several organizations dedicated to preserving African-American family histories in Virginia. 2 weeks after posting her inquiries, Amelia received an email that made her heart race. It was from a woman named Dorothy Freeman Williams, a 68-year-old retired teacher living in Washington DC who identified herself as Clara and Daniel Freeman’s great great granddaughter.

I’ve been researching my family history for years. Dorothy wrote, “When I saw your post about a photograph from 1875, I immediately thought of the portrait my grandmother told me about, the one that Clara insisted on having made, even though it was expensive. I have documents and stories that have been passed down through our family. I’d very much like to speak with you about what you’ve discovered.

” They arranged to meet at the museum. The following week, when Dorothy arrived, she carried a worn leather portfolio that had clearly been carefully preserved for generations. She was a dignified woman with kind eyes and a warm smile. But Amelia could see the emotion in her face as she looked at the photograph displayed on Amelia’s desk.

“That’s them,” Dorothy said softly, tears welling in her eyes. “That’s my great great grandparents and their children. I’ve heard stories about this photograph my whole life, but I’ve never actually seen it.” After my grandmother passed away in 1983, we lost track of where the original had gone. One of my cousins must have had it and decided it belonged in a museum. Dorothy sat down and opened the portfolio.

My grandmother, Ruth Freeman, the girl standing on the right in this photograph, she told me Clara’s story many times before she died. She wanted to make sure it wasn’t forgotten. She pulled out a handwritten document. Pages yellowed with age, but the ink still legible. And this is an account that Clara herself wrote in 1889, 14 years after this photograph was taken.

She was learning to read and write. She’d been forbidden education during slavery. and one of the first things she wanted to do was record her own story in her own words. Amelia’s hands trembled slightly as Dorothy passed her the document. The handwriting was careful and deliberate, the work of someone who had learned to write as an adult, but had important things to say.

My name is Clara Freeman, the document began. I was born Clara Hayes in 1831 on the Hartwell Plantation in Lancaster County, Virginia. I do not know the exact date of my birth as such things were not recorded for enslaved people, but I was told I was born in spring when the tobacco was being planted.

I lived my entire life until age 33 in bondage to the Hartwell family. I worked in the tobacco fields from the time I was 6 years old until the day I escaped during the confusion of the war. I married my first husband when I was 16, a man named Joseph who was sold away from me two years later. We had a daughter who died of fever before her first birthday. The Heartwells were not kind masters.

When I was 14, I tried to run away to find my mother who had been sold to a plantation in North Carolina. I was caught after 3 days. As punishment, I was shackled at the wrists and ankles for 6 months. The metal cut into my skin, leaving scars I carry to this day.

Over the years, I received many lashings for various offenses, working too slowly, speaking when not spoken to, attempting to learn to read. Each punishment left its mark on my body. By the time I was 30, my arms were covered with scars from wrists to shoulders, permanent testimony to the cruelty of the institution that held me captive. Dorothy watched Amelia’s face as she read, understanding the weight of the words her ancestor had written.

When Amelia looked up, Dorothy continued the story that Clara’s written account didn’t fully tell. Clara escaped in 1864. Dorothy explained Richmond was under siege and there was chaos throughout Virginia. The Heartwell Plantation was struggling. Most of the enslaved men had already run away to join the Union Army or fled north.

Clara saw her chance and took it. She walked for 3 weeks, hiding during the day, traveling at night, until she reached Richmond and found refuge with the Union forces that had occupied the city. Dorothy pulled out another document, a faded certificate from the Freriedman’s Bureau. This is the document that officially recognized her freedom.

It’s dated April 1865, just after the war ended. She was 34 years old and had spent her entire conscious life in slavery. “That’s when she met Daniel,” Amelia asked. Dorothy nodded. Daniel was a free black man. His parents had purchased their freedom in the 1820s, and he’d been born free.

He was working as a carpenter, helping to rebuild parts of Richmond that had been damaged during the war. They met at a church service and married within 3 months. My grandmother Ruth said that Daniel was the first person who treated Clare with genuine kindness, who saw her as a complete human being with value and dignity. She pulled out a letter, this one in different handwriting, more educated and flowing. This is a letter Daniel wrote to his sister in 1870.

Listen to this passage. Clara is the strongest woman I have ever known. She endured horrors I cannot fully comprehend. Yet, she faces each day with determination and grace. She works harder than anyone I know, tending our home, raising our children, and helping with my carpentry business. But I see how she carries the weight of her past.

She will not allow anyone to see her arms uncovered. She makes her own long sleeves for all her dresses and wears gloves whenever she leaves the house. She says the scars remind her too much of what she survived.

And she does not want our children to grow up seeing those marks and thinking of their mother as a victim. She wants them to see her as strong and whole. Amelia felt tears sting her eyes. The photograph suddenly made complete sense. Clara had insisted on wearing those long gloves not out of shame, but as an act of self-defin. She refused to let the physical evidence of her enslavement define how her children and history would remember her.

“Tell me about the photograph,” Amelia said gently. “Why was it taken?” Dorothy smiled, though tears were running down her cheeks. According to Family Stories, it was Clara’s idea. In 1875, they had saved enough money to own their home, and all four children were healthy and thriving.

Clara told Daniel that she wanted a portrait made, a formal portrait that showed the world what they had built together. She wanted proof that a woman who had been treated as property, who had been brutalized and dehumanized, could not only survive, but thrive. She wanted a photograph that showed her family’s dignity, success, and humanity. Dorothy pulled out one more document, a receipt from J.

Morrison’s photography studio, dated June 15th, 1875. The cost had been substantial, $5, nearly a week’s wages for a skilled carpenter at that time. Clara insisted on going to Morrison because he was known for treating black clients with respect. She chose her finest dress and had Daniel commission those special gloves from a seamstress. She wanted everything to be perfect.

And the inscription on the back, Amelia asked. May we never forget. What did that mean? My grandmother explained that to me, Dorothy said. Clara meant it as a reminder to her descendants. She wanted us to remember where we came from. The suffering, yes, but also the strength.

She wanted us to remember that freedom is precious because she knew what it meant to live without it. and she wanted us to remember that no matter what scars we carry, we have the right to define ourselves on our own terms. As Amelia continued her research, working closely with Dorothy, she uncovered more layers to Clara’s story.

Dorothy shared family letters, documents, and oral histories that had been preserved across five generations, each adding depth and context to the photograph and the woman at its center. One particularly revealing document was a diary kept by Ruth Freeman, the young girl in the photograph who would become Dorothy’s great-g grandandmother. Ruth had started the diary in 1880 when she was about 15 years old, and she had written extensively about her mother, Clara.

Mama never talks much about her time before freedom. Ruth had written in an entry from 1881. But sometimes at night, when she thinks we are all asleep, I hear her crying softly. I asked her once about the scars on her arms. I’d glimpse them accidentally when she was washing, and she told me that they were reminders of a past that no longer had power over her.

She said that when she looks at her arms, she could choose to see either the cruelty that made those marks or the strength that survived them. She said she prefers to cover them not because she is ashamed, but because she wants people to see her as she is now, not as she was forced to be then. Another entry from 1883 provided insight and declares determination to create a different future for her children. Mama is fierce about our education.

She walks us to school every day and meets with our teachers regularly. She says that the ability to read and write was denied to her and she will not allow anything to stand in the way of her children having that gift. Papa says that Mama has taught herself to read better than many people who went to school their whole lives.

She reads every newspaper she can find and has begun writing down family stories so that we will always remember where we came from. Amelia also discovered that Clara had become active in Richmond’s black community organizations in the years after the photograph was taken. Records from the First African Baptist Church showed that Clara was involved in establishing a mutual aid society for formerly enslaved women, providing support, resources, and community for women who were building new lives after emancipation.

In the church archives, Amelia found minutes from a meeting in 1878, where Clara had spoken to a group of young women who had recently arrived in Richmond from rural Virginia, seeking opportunities in the city. According to the notes, Clara had told her story, not dwelling on the suffering, but emphasizing the possibilities of freedom and the importance of community support. Mrs.

Freeman spoke powerfully about her journey from bondage to freedom. The notes recorded, “She told the assembled women that the scars we carry, whether visible or invisible, are proof of our survival, not evidence of our defeat. She encouraged each woman to hold her head high, to demand respect, and to build a life defined by her own choices rather than by what had been done to her.” Dorothy shared one final document that particularly moved Amelia.

A letter Clara had written to her daughter Ruth in 1890 when Ruth was planning her own wedding. The letter offered advice, blessings, and reflections on marriage and family. When your father and I married, Clara had written, “I was broken in many ways. My body bore the marks of cruelty, and my spirit had been bent by years of having no control over my own life.

Your father could have been repelled by my scars or intimidated by the weight of my past. Instead, he saw me as I wished to be seen, as a woman of strength and dignity, capable of building a future rather than being defined by the past. That photograph we had made when you were young.

Do you remember it? I wore those long gloves not because I was ashamed of my scars, but because I wanted that portrait to show our family as we are, not as we were shaped by slavery. I wanted you children to see yourselves as free people born into freedom with possibilities your father and I never had. The scars on my arms are real and I do not deny them. But they are not the whole truth of who I am.

I’m also a wife, a mother, a member of a community, a woman who survived and built something beautiful from the ashes of bondage. As Amelia prepared her exhibition about the Freeman family photograph, she knew it was crucial to provide historical context that would help visitors understand Clara’s story within the larger framework of American history. She reached out to Dr.

Marcus Bennett, a colleague who specialized in the history of slavery and reconstruction in Virginia. Together, they compiled statistics and information that painted a stark picture of the world Clara had survived. In Virginia alone, nearly half a million people had been held in slavery before emancipation.

The conditions on tobacco plantations like the Hartwell estate were notoriously brutal. Enslaved people worked from sunrise to sunset during planting and harvest seasons with minimal food, inadequate shelter, and constant threat of punishment. Physical punishment was routine and severe. Research into plantation records and formerly enslaved people’s testimonies, revealed that whipping was one of the most common forms of discipline, often applied for minor infractions or simply to maintain control through fear.

Shackling was used as punishment for attempted escape or perceived rebellion, with enslaved people sometimes forced to wear iron restraints for weeks or months at a time. The scars Clara carried were unfortunately typical of enslaved people who had survived the plantation system, particularly those who had shown any sign of resistance or independence.

Marcus helped Amelia understand that Clara’s experience, while individual and personal, was also representative of millions of others who suffered similar brutality. But Amelia also wanted the exhibition to emphasize what came after emancipation, the remarkable resilience and achievement of formerly enslaved people in building new lives.

Richmond had become a center of black economic and cultural life in the years following the Civil War. By 1870, the city had a thriving black business district. Numerous churches, schools, and mutual aid societies. Formerly enslaved people had established themselves as property owners, skilled craftsmen, teachers, ministers, and community leaders.

The Freeman family success was significant, but not unique. Thousands of formerly enslaved people had made similar journeys from bondage to self-sufficiency in the decade after the war. Their achievements were even more remarkable given the obstacles they faced.

Not just the trauma of their past experiences, but also the active resistance of white supremacists who sought to prevent black economic and social advancement. Amelia discovered that Daniel Freeman’s carpentry business had grown substantially in the years after the photograph was taken. By 1880, he employed three other carpenters and was taking on major contracts for building projects throughout Richmond.

The family had moved to a larger house and all four children had received education beyond basic literacy. Ruth and Margaret had attended normal school to become teachers. While Elijah and Samuel had learned trades, Clare herself had continued her own education, learning not just to read and write, but also to keep business accounts.

Records showed that she had managed the financial side of Daniel’s carpentry business, handling contracts, payments, and correspondence. By 1885, she was listed in city directories as a property owner in her own right, having purchased a rental property that provided additional income for the family. Dorothy provided Amelia with one particularly moving piece of evidence, a newspaper clipping from 1888 when Clara had been interviewed for an article about successful black businesses in Richmond. The article was brief, but it quoted Clara directly.

We have built something here that no one can take away from us. Not just property or business success, but dignity and self-determination. My children were born free. They will raise their own children in freedom. That is worth more than any amount of money. On a warm spring evening in May 2025, the American Legacy Museum hosted the opening of Hidden No More, the story of Clara Freeman and the Long Gloves.

The exhibition had been carefully curated to tell Clara’s story with both honesty about the brutality of slavery and celebration of her resilience and achievement. The centerpiece was the 1875 photograph, dramatically displayed with specialized lighting that allowed visitors to see both the original image and on an adjacent screen.

The enhanced analysis that revealed the scarring beneath Clara’s gloves. Panels throughout the gallery provided historical context, explained the significance of the photograph, and traced the Freeman family’s journey from slavery to freedom to prosperity. Dorothy Freeman Williams stood near the entrance with several other Freeman family descendants.

Over 20 family members had traveled to Richmond for the opening, representing five generations of Clara and Daniel’s descendants. The family included teachers, doctors, engineers, artists, and business owners, all of them carrying forward the legacy of resilience and achievement that Clara had established.

The gallery was packed with over 400 people, historians, community members, descendants of other formerly enslaved families, students, and members of the press. Local and national media had covered the story extensively, drawn by the combination of cuttingedge technology revealing hidden history and the powerful human story at its center. Amelia stood at the podium to address the assembled crowd.

Behind her, the enlarged photograph showed Clara’s dignified face, her careful pose, and those long gloves that had hidden so much yet revealed so much more. For 149 years, Amelia began, “This photograph has existed as a beautiful portrait of a successful black family in post civil war Richmond.

But modern technology has allowed us to see what Clara Freeman deliberately chose to conceal. The physical scars of the brutality she survived. Yet, in understanding what she hid and why she hid it, we discover something even more powerful. Clara’s profound act of self-defin and resistance. Clara Freeman did not hide her scars because she was ashamed of them.

She hid them because she refused to be defined by them. She wanted this photograph, this permanent record of her family to show not what had been done to her in slavery, but what she had built in freedom. She wanted her children and all future generations to see her as a woman of strength, dignity, and achievement. Amelia gestured to the family members gathered in the gallery.

Clara’s descendants are here tonight living proof of what she and Daniel built together. They include educators, physicians, business leaders, artists, and activists. People who have achieved things that Clara herself, denied education and opportunity for most of her life, could only dream of. Yet, all of them carry forward the values she embodied.

Resilience, dignity, self-determination, and commitment to family and community. Dorothy stepped forward to speak, her voice strong despite the emotion evident in her face. My great great grandmother Clara died in 1904 at the age of 73. In the final decades of her life, she saw her children grown and successful, her grandchildren born into a world very different from the one she had known.

She saw her community continue to thrive despite the increasing restrictions and violence of the Jim Crow era that was taking hold. According to family stories, Clara was asked near the end of her life whether she had any regrets about hiding her scars in the photograph rather than displaying them as evidence of what she had survived.

She reportedly said, “I wanted the world to see what we built, not what they tried to break. The scars were real, but they were not the truth of who I was. The truth was in my freedom, my family, my dignity. That’s what I wanted the photograph to show.” Dorothy’s voice broke with emotion. On today, we honor Clara by telling her full story and of the suffering she endured and the strength she embodied.

We honor her by showing both what was hidden and what was proudly displayed. And we honor her by continuing to build on the legacy she established, refusing to be defined by what has been done to us, always moving forward with dignity and determination. The exhibition remained open for 8 months and was visited by over 50,000 people.

It sparked conversations about how history is remembered, how trauma is carried and processed, and how individuals and communities define themselves in the aftermath of systemic oppression. The photograph itself became an iconic image reproduced in textbooks, documentaries, and educational materials about the post civil war era and African-American history.

But perhaps the most significant impact was on how people thought about historical photographs themselves. Amelia wrote an article for a major academic journal arguing that many historical images contain hidden stories, not just in what they show, but in what their subjects chose to reveal or conceal.

The Clara Freeman photograph became a case study in how modern technology combined with careful historical research and attention to family narratives could unlock stories that had been preserved but not fully told. The American Legacy Museum established the Clara Freeman Research Fellowship, providing funding for scholars studying the experiences of formerly enslaved women and the strategies they used to survive, resist, and rebuild their lives after emancipation.

Dorothy Freeman Williams donated additional family documents and artifacts to the museum’s collection, ensuring that Clara’s story would continue to be told with depth and accuracy. 6 months after the exhibition opened, Amelia received a letter from a woman in North Carolina. The writer explained that she’d visited the exhibition and been moved to research her own family history.

Through genealological research, she had discovered that her great great grandmother had also been enslaved on the Hartwell Plantation in Lancaster County at the same time as Clara. The woman included a photograph from 1880. Her ancestor standing with her family, also wearing long gloves despite the summer heat. Reading Clara’s story helped me understand my own ancestors choice, the woman wrote.

I always wondered about those gloves in the photograph. Now I understand that she too was making a statement, not hiding in shame, but asserting her right to be seen as she chose to be seen. Amelia realized that Clara’s story was resonating because it spoke to something universal.

the human desire for dignity, the right to self-defin, and the complex relationship between acknowledging trauma and moving forward from it. Clara hadn’t denied her past. She had simply refused to let it be the only lens through which she was viewed. One afternoon, several months after the exhibition opened, Amelia stood alone in the gallery, looking at the photograph that had started this entire journey.

She thought about Clara, her strength, her determination, her careful choice to cover those scars while building a life of purpose and meaning. The photograph had always shown a family portrait, but now it revealed so much more. A testament to survival, an act of resistance, a declaration of dignity, and a bridge between past and present. Clara’s gloves had hidden her physical scars.

But in doing so, they had preserved a more complete truth about who she was. Not just a survivor of slavery, but a woman who had built a life of freedom, family, and community. Behind Amelia, a group of middle school students entered the gallery with their teacher.

She listened as the teacher explained Clara’s story, watching the students faces as they processed what they were learning. One girl raised her hand. “Did Clara ever take off the gloves?” the girl asked. “Did she ever let people see her arms?” The teacher smiled gently. According to the family accounts, Clara was selective about when she revealed her scars.

She showed them to her children when they were old enough to understand, using them as a teaching tool about history and resilience. She showed them to other formerly enslaved women in her community, as a way of building solidarity and understanding. But she chose when and where and to whom she revealed that part of her past. That choice itself was an expression of her freedom. The students nodded thoughtfully, looking back at the photograph with new understanding.

Amelia thought about the note that had arrived with the photograph months earlier. Please tell her story. That simple request had opened a window into a remarkable life and revealed a truth that had been both hidden and preserved for 149 years. Clara Freeman’s story was now told not just the story of what she survived, but the story of how she chose to be remembered.

The long gloves in the photograph were no longer simply an unusual fashion choice. They were a powerful statement of self-determination, a reminder that healing from trauma doesn’t require displaying wounds and a testament to the fact that freedom includes the right to define oneself on one’s own terms.

As visitors continued to move through the gallery, examining the photograph and reading Clara’s story, Amelia understood that this was exactly what Clara had wanted all along. Not to hide the truth, but to ensure that when people looked at her family portrait, they saw the full truth. Not just survivors of slavery, but builders of freedom, dignity, and legacy.

The gloves had hidden Clara’s scars, but the photograph, properly understood, had preserved her story. And now finally that story was being told with the depth, respect and understanding it deserved.