Chapter 1: SAAB J35 Draken – The Neutral Superpower Draken’s story started back in late 1949, in a small Swedish town, where a young engineer named Erik Bratt was staring at a seemingly impossible problem with nothing but pencil, paper, and a slide rule to solve it. News of the Bell X-1’s supersonic flight had reached Sweden in 1947.

For most of the world, it was a technological milestone—proof that humans could break the sound barrier and live to tell the tale. For the small engineering team at Svenska Aeroplan, better known as SAAB, it was something else entirely. It was an invitation. If supersonic flight was possible, then Sweden’s next fighter would be supersonic.

That decision was made almost immediately. What wasn’t clear was how to actually build one. The question is, why would Sweden, a country with a population less than 7 million people, need or want to build their own in-house supersonic aircraft? Well, it was because Sweden had a problem that few other countries faced.

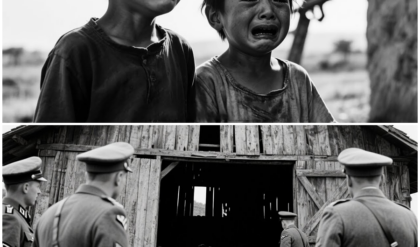

Sweden was at the time Neutral and had been since 1814 after the Napoleonic wars and this neutrality she couldn’t rely on anyone else to defend her. Because nine years earlier, in April 1940, German forces had seized Norway’s Oslo Airport. Within months, the American government had cut off deliveries of the 316 aircraft Sweden had ordered, worried they may end up in German hands.

Only 62 ever arrived. The rest vanished into American inventory. Sweden were forced to buy whatever other countries were willing to sell. But only ones selling were Italy, but obsolete Fiat biplanes and Reggiane fighters that were at least current-generation were not enough. It was desperation procurement. But in 1940, Sweden had no choice.

At the stroke of a pen, Germany’s invasion of Oslo had become Sweden’s Pearl Harbor. This was a clear demonstration that in a world at war, a neutral country could only depend on their own domestic aircraft industry otherwise they run the risk of being effectively defenseless. That experience led to the Swedish government’s November 1940 Basic Agreement with SAAB, which formalised production commitments: at least 1,100 combat aircraft by mid-1946, with production rates up to 30 aircraft per month if required. But they weren’t starting from scratch.

Before the agreement, aircraft that would fulfill these commitments had already been in development. SAAB had taken over another aviation firm, ASJA, in March 1939, inheriting their project that became the Saab 17 dive-bomber along with the twin-engined Saab 18.

Then there was the J 21 in 1943—Sweden’s first significant indigenous fighter, and the first real product to emerge from that Basic Agreement. It was also one of the only combat aircraft ever used operationally in both propeller-driven and jet-powered versions—the other being the Soviet Yak-15, though that was less a conversion and more a jet engine grafted onto an existing airframe. Let me know in the comments if there are any others.

By 1948, SAAB had already flown the J 29 Tunnan, or “the Barrel”, of which six hundred and sixty-one would roll off the production lines. That track record—going from desperate 1940 procurement to delivering hundreds of Tunnans was a huge industrial achievement that no doubt needed managing thousands of contracts, schedules, and suppliers. And speaking of keeping track of what’s been delivered and what hasn’t.

I used to run a small business for many years, and as any small business owner knows, you have to wear every hat—sales, marketing, legal, customer service, tech support, and tea boy. Don’t get me wrong—we love landing new customers, doing the actual work, seeing the business do well. But there was one task that irked me to no end: the aftermath.

Generating invoices, keeping track of what had been paid, what was outstanding, who needed a gentle reminder, who’d conveniently “forgotten” to pay for three months. Then came the end-of-year accounts—making sure all the invoices were in order, cross-referencing bank statements, finding that one I’d sworn I’d sent but had somehow ended up forgotten in the glove box of my car.

Keeping track of all the paperwork was a monumental pain in the . Hours I could’ve spent actually growing the business were instead spent chasing numbers in spreadsheets. That’s why Odoo Invoicing is a revelation. Creating an invoice used to take me ten minutes of faffing about with templates. Now? Seconds.

You identify your customer, add the products or services, specify quantities, set your payment terms—due date, payment reference, the lot—and hit send. Done. The invoice goes out by email, and you can track everything from one place: what’s been paid, what’s outstanding, who needs chasing. Better yet, your customers can pay online through the portal using whatever method they prefer—Stripe, PayPal, whatever works for them.

No more waiting for cheques in the post or wondering if the bank transfer went through. And here’s the clever bit: you can connect your bank account and automate the whole follow-up process. Clear payment statuses, due dates, reminders—all sorted without you lifting a finger. And if you’re dealing with clients in Europe, Odoo’s got you sorted for the upcoming electronic invoicing regulations. Starting January 2026, countries like Belgium are making B2B electronic invoicing mandatory. Odoo includes Peppol—that’s the secure European invoice network—and you can activate it with a single click. Free. No additional fees, no complicated setup. You’re legally compliant without even thinking about it. But wait, there’s more—the most splendid part? Odoo’s first app is free for life,

so you can start for free. For life. So if you’d rather spend time building your business rather than building mountains of paperwork, click the link in the description and give Odoo’s Invoicing app a try. Thank you to Odoo for sponsoring this video. Right, back to Erik Bratt’s supersonic problem.

So, come 1949, Sweden knew how to build capable fighters, now they just had to build a supersonic one, and quickly. Because across the Baltic Sea within easy reach sat an adversary that had just acquired nuclear weapons. And it would only be a matter of time before their squadrons of Tupolev Tu-4 bombers could carry the bomb to western targets.

Finland on the eastern border wasn’t much of a buffer—they’d been forced into constrained neutrality after the Winter War, walking a fine line to keep the Soviets happy while staying technically independent. And that border with the Reds was close. Too close for comfort.

It didn’t help that Norway’s NATO membership complicated Sweden’s western border, putting them squarely in the path of any Soviet bomber heading for Norwegian targets—or using their airspace as a corridor to the Atlantic. It was feared that in the time it took to brew a pot of coffee, the skies above Sweden could be darkened by hundreds of Soviet bombers. The Swedish response was pragmatic: if we can’t join an alliance, we’ll defend our neutrality by making violations expensive.

Sure, fighters couldn’t stop nuclear missiles, but in 1949, nuclear weapons were expected to be delivered by bombers that had to fly to their targets. Unfortunately for Sweden, her geography put them directly in the path of any Soviet bomber route heading west.

Sweden wasn’t going to give Moscow a free corridor through their airspace. Every Soviet bomber crossing Swedish territory was going to have to fight for every mile. Make that fight costly enough, and maybe they’d think twice about violating Swedish neutrality in the first place.

And to do this what Sweden needed was something that could climb hard and fast to catch anything the Soviets sent and potentially bring it down. With this in mind, in September 1949, the Swedish Air Board released Project 1200 that laid out requirements for their next interceptor. By October, SAAB received the formal study contract. The specifications were brutal. One mission: bring down Soviet bombers.

To do this, the aircraft needed rapid interception capability—a climb rate fast enough to reach high-flying intruders before they entered Swedish airspace. And they had to intercept them day or night, regardless of conditions. In time, the definitive J 35 would have a climb rate of almost 40,000 feet per minute.

To put that in perspective, a combat loaded Soviet MiG-21 could hit 46,000 feet per minute, and only one European interceptor could outclimb the Swedes—the English Electric Lightning at 50,000 feet per minute. Draken could and would hold her own in very fast company.

It would be single-engined—not because Sweden wanted to save money, but because a twin-engine interceptor would be heavier and slower-climbing. For intercepting high-altitude bombers, climb rate mattered more than redundancy. But Erik Bratt’s team knew better. The Tu-4 may have been slow and lumbering, but it was already operational, and the Swedish engineers knew the Soviets wouldn’t stop there—their bombers would soon be faster and flying higher.

So, even though the Project 1200 requirement specified a maximum speed of Mach 1.4, Bratt understood that any interceptor design would also need built into it the ability to go faster—much faster. The so-called “Speed Creep.” And then came the requirements that made everything else nearly impossible.

Sweden’s entire Cold War air-defense doctrine—Bas 60—was built around dispersal. If war came, Swedish aircraft wouldn’t be sitting on big air bases waiting to be destroyed. They’d be scattered across the country on wartime road bases hidden in forests, using reinforced public roads as runways.

A typical wartime strip was roughly 800 meters long and 12–13 meters wide. The logic was brutal but sound: scatter fighters across dozens of small, camouflaged bases, and a pre-emptive strike becomes prohibitively expensive. You can’t destroy what you can’t find, and you can’t find it if it’s been well hidden in a forest. But dispersal created a different problem: support.

The people servicing these dispersed aircraft wouldn’t necessarily be seasoned technicians—they’d mostly be conscripts, eighteen-year-olds with basic training. The aircraft had to be designed so those conscripts could refuel, rearm, and turn them around in under ten minutes, using minimal tools, sometimes in the dark, often wearing thick gloves.

If the aircraft wasn’t maintainable under those conditions, then the entire Bas 60 doctrine didn’t work. This was the entire plan. But there was an issue. In 1949, nobody had built anything remotely like this. And that was the problem 33-year-old Erik Bratt was pondering when he was handed Project 1200.

So who was this engineer on which Sweden was gambling its future? Erik Bratt had been with SAAB since 1945 after spending three years with Skandinaviska Aero. By 1949, he’d been assigned as Project manager responsible for supersonic aircraft development. But he was told not to worry—the position was temporary, just until someone more experienced could be found.

However, there was a slight complication: of the 7 million people in Sweden, nobody had experience designing supersonic fighters. What are the odds? As Bratt himself later noted, “There simply weren’t any supersonic aircraft around, apart from the experimental Bell X-1.” To nobody’s surprise, no one with more experience showed up. Congratulations, Bratt. The job’s yours. But Bratt was no rookie.

He earned his engineering degree from the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm in 1942—the country’s most prestigious university for engineering. But his education wasn’t confined to the classroom.

He’d already earned his pilot’s license in 1937 at age 21, then trained as a reserve pilot in the Swedish Air Force between 1940 and 1942—one of the “Silver Wings,” the name given to reservists. He understood aircraft from both sides: the cockpit and the drawing board. That combination—pilot and engineer—would prove essential. Bratt knew what pilots needed and what ground crews could manage under Bas 60 conditions.

The core team started small, with just twelve engineers in late 1949, but by the time Draken reached production, more than 500 engineers and technicians would be working on the program, at SAAB’s facility in Linköping. Their task was simple to state and almost impossible to execute. However, Bratt’s team weren’t on their own.

Unlike the American Operation Paperclip which had taken hundreds of German scientists, or the Soviets who grabbed whomever they could, Sweden found themselves with just a handful of German engineers. Three of them, Klaus Oswatitsch, Siegfried Erdmann, and Hermann Behrbohm, were ex-Peenemünde and Messerschmitt aerodynamicists, who had been through various allied hands before ending up in Sweden.

These men undoubtedly helped design Draken, teaching the Swedes how to think about supersonic flight. They brought test methodologies, engineering knowledge, and hard-won lessons from a decade of German research that would’ve taken Sweden years to rediscover on their own. Sweden was building Draken alone. But they weren’t starting from zero.

One of the first problems they had to solve was wing geometry. Swept, delta, variable geometry—what shape would work? They soon learned they were caught in a catch-22 situation. Low-speed handling for motorway strips and high supersonic performance are a tradeoff. Swept wings—like those on the F-86 Sabre or MiG-15—work well around Mach 0.8.

Good handling, reasonable landing characteristics. But at speeds past Mach 1.4 or 1.5, wave drag became a serious problem—one that would challenge every supersonic fighter program in the 1950s. Swept wings couldn’t get you to high supersonic speeds efficiently. So they turned to pure delta wings.

Deltas keep drag low at high speed and stay structurally efficient, ideal for pushing well beyond Mach 1.4. But there’s always a but. A pure delta wing doesn’t generate much lift at low speed unless the aircraft flies at a very high angle of attack, relying on powerful leading-edge vortices. The aircraft has to pitch its nose way up, sometimes 15 or even 20 degrees.

When it does, the airflow separates from the sharp leading edge and rolls into two tight vortices running along the top of the wing, creating low pressure that sucks the aircraft upward. This is why pure-delta fighters like the Mirage III come in nose-high, looking like they’re trying to sit back on their tails. They’re riding those vortices all the way to the tarmac.

It works—but it comes with high approach speeds and long landing distances. Given the knowledge at the time, a pure delta couldn’t have operated from Sweden’s wartime motorway strips. By late 1949, Project 1200 design studies were piling up. Some with swept wings. Some with pure deltas. Some with tail surfaces. Some without.

All manner of variations in between. And nothing worked. Swept wings hit a wall at high Mach numbers. Pure deltas couldn’t land short enough. The requirements seemed mutually exclusive. You can optimise for one, but you’ll pay for it in the other. The team couldn’t settle on anything because nothing satisfied all requirements simultaneously.

But they had to find a solution, because if they failed, Sweden’s interceptor program died. The Swedish Air Force would be stuck flying upgraded Tunnans while Soviet bombers got faster and more capable. The Americans weren’t likely to be selling any upcoming supersonic fighters to neutral countries. And, as for the British, well, the Lightning was still years away from service.

Then an idea was proposed. One so radical that many doubted it would even work If the swept wing could do one job and the delta could do the other, then why not use both? Chapter 2: SAAB J35 Draken – Double or Nothing Imagine this: A design meeting at SAAB’s Linköping facility. Erik Bratt walks in, carrying a blueprint for a wing design. He unrolls it in front of his colleagues.

Some of the engineers sit up and stare, taking a moment to fully grasp what they’re looking at. Others laugh nervously. Maybe a few of the old-salt veteran aerodynamicists look at it with dismay. One or two might have said: “That’ll never fly.” The drawing shows a wing that looks more like a bent and broken triangle. It looks wrong. Just unnatural.

Nothing with a wing like that could possibly fly. Now, I don’t know if this meeting actually happened—but Bratt and his colleagues were playing a high-stakes game with an unusual, untested configuration that was Sweden’s shot at supersonic interception. Bizarre looking as the wing design was, the man behind the drawing wasn’t reckless.

Far from it. Erik Bratt wasn’t a mad scientist sketching triangles on napkins. He was the kind of engineer who would triple-check a calculation before letting anyone else see it. He understood personally that if he missed a decimal point somewhere, someone would eventually pay for it with their lives.

And yet, he was also the one willing to bet his reputation, and possibly Sweden’s entire air defense on a wing that looked like it had been snapped in half. So how did they get to this odd-looking wing? By November 1949, Bratt’s team had been examining every option they could think of. They’d started with a plain delta.

The wingspan and overall dimensions had been determined by the ceiling requirement and the root chord was fixed by the fuel volume needed for the intercept mission. But after much study they calculated a pure delta sized for fuel volume and high altitude flight had far more wing area than necessary for transonic and supersonic performance. And this was bad.

In the transonic regime—right before and just beyond Mach 1—any excess wing area generated severe wave drag, an aerodynamic penalty that made even small design compromises feel like pushing a barn door through the sky. But if they reduced the wing area, the landing speeds and distances would increase So they had a problem.

They needed a thick enough wing to hold fuel and landing gear, which inevitably produced too much area—destroying their transonic and supersonic performance—yet the smaller area they wanted for high-speed flight would make the airplane unforgiving on approach. Standard delta logic said: pick your compromise and live with it. But Bratt’s team asked a different question: what if we didn’t compromise? The answer: keep the wing thick and deep where you need the volume—near the fuselage—but reduce the unnecessary area further out.

The sharp crank in the leading edge was the cleanest way to do exactly that: a sharply swept inner section for high-speed performance, and a less aggressive outer section for low-speed lift and control—perfect for landing on short forest roads. This clever combination also had the benefits of the “area rule”—normally seen on specially shaped fuselages like the B-58 and F-102 without needing the fuselage to be narrowed into a coke-bottle shape or adding extra bumps. But the magic was in the specifics, now brace

yourselves, the next section is cracking.. So, Draken’s 80-degree swept-back inner wing behaved aerodynamically like a razor-thin wing, far thinner than it actually was, this allowed the aircraft to reach and maintain supersonic speeds without suffering the massive drag penalties a thick wing would normally impose. This was all thanks to the long chord relative to its thickness.

By keeping the thickness-to-chord ratio low, the inner wing performed like a thin wing at high speed, yet retained a physically deep root to house fuel, landing gear, and avionics—all the volume the aircraft needed, without paying the usual drag penalty. Every component was strategically tucked behind something else: the engine behind the pilot, fuel tanks and main landing gear behind the intakes.

The wing essentially became part of the fuselage—a blended wing-body decades before the term became common. So, that’s high speed flight and internal volume sorted, what about low-speed and coming into land at short strips, Well, at low speeds, the outer panels behaved like a conventional, moderately swept wing, but the real magic came from the 80° inboard leading edge.

Any time Draken pitched nose-up, whether in a hard turn or flaring for landing , the inner wing would begin to generate a pair of vortices. These spinning tunnels of air would stay tight and coherent as they swept across the crank or dog-tooth and out over the outer panels, all the way to the wing tips, By keeping the airflow firmly attached, the vortices generated a huge amount of extra lift.

That extra lift let Draken fly slowly, nose-high, while remaining fully controllable. It’s not surprising this is called the Leading-edge vortex lift principle or in SAABs documentation, simply the Double-delta vortex lift. While almost every other delta-wing fighter of the era reached their limits around 16 to 18 degrees; beyond that, the wing would stall, Draken could safely pitch its nose to 26–28 degrees—and keep flying.

As the angle of attack increased, the vortex suction moved forward, moving the center of pressure with it and giving natural pitch stability all the way to the stall limit. In effect, the aircraft gained nearly ten extra degrees of “free” lift, purely from the shape of its double-delta wing. The payoff was enormous.

Pilots could make slow, controlled approaches to short strips, with landing rolls of around 800 meters in the early Draken—and much less when using a drag chute and lift dumps. It was like having built-in leading-edge flaps—but without any moving parts. The wing itself did all the work. On the drawing board it solved everything. High supersonic performance from the inner wing. Slow-speed handling from the outer wing.

All the internal volume and strength they needed. Two deltas. One wing. No horizontal tail. It’s sort of simple when you think about it — and it’s why Draken looks the way it does. But SAAB weren’t putting all their eggs in one basket.

At the same time, they’d been running a parallel study—Project 1220, a more conventional swept-wing supersonic aircraft. Project 1220 was supposed to be the safe bet. SAAB had already built a swept-wing fighter and were working on the J.32 Lansen; they understood the risks, the quirks, the limits. They were working with proven, predictable aerodynamics.

But once the numbers came in, the safer option started to show its limits. As we know, a swept wing could meet the short-field requirement—landing on road bases, taking off from improvised strips. That part was manageable. But pushing past Mach 1.4? The drag numbers spiked like hitting a brick wall. They’d need a bigger engine, more fuel, more structure—and that meant more weight making the low-speed problem worse. It was a vicious circle. The double-delta broke that circle.

On paper, it solved everything Project 1220 couldn’t. But not everyone was convinced. Even after the numbers showed the double-delta’s advantages, some kept pushing for the conventional swept-wing design. Even the Swedish Air Board second in command, Major General Bengt Jacobsson, was not impressed when he paid a visit to SAAB to take a look at what they’d been up to.

Bratt and SAAB’s chief project leader Lars Brising walked him through both configurations—the radical double-delta with no tail and the more conventional layout with a swept wing and horizontal stabilisers. They laid out the advantages and disadvantages, the performance trade-offs. The risks. After the briefing, Brising asked if the Major General had anything to add. Jacobsson’s response was blunt: “You can build the damn plane however you want, but it SHALL have a tail!” And it wasn’t without merit.

A tailless aircraft made people nervous. There were stability concerns and questions around control authority. After the general left, Bratt and Brising had a quiet conversation. They agreed to make drawings of the double-delta with a tail—something they could pull out and show during future visits from prying air force officials. It was a hedge.

A way to keep everyone calm while they kept working on what they knew was the better solution. But the debate didn’t end there. Some time later, Erik Bratt got a phone call that Chief of the Air Force Bengt Nordenskiöld would be coming up and would SAAB kindly present their thoughts on the new supersonic interceptor? Once again Bratt and Brising laid out both alternatives—the swept wing and the double-delta. The same trade-offs, the same calculations, the same risks.

When they had finished, Nordenskiöld asked a simple question. “Which aircraft is best?” Bratt didn’t hesitate. “In my opinion, the double-delta is best.” Nordenskiöld looked at him. “Then why are you working on anything else? From now on, you work ONLY on that aircraft.” And with that, the Air Force Chief stood up and left the room. The decision had been made. No more hedging.

No more drawings with tails to show nervous generals. By May 1950, Project 1220 was formally shelved. Sweden had just gone all-in on the double-delta nobody had ever flown before. This radical wing—the one that looked like a broken triangle—was now Sweden’s only bet.

But drawings and equations can only get you so far. Could it actually fly? What they needed was a wind tunnel. The problem was that Sweden had exactly one supersonic wind tunnel in 1950, which sounds impressive until you realize it could only test 1:50 scale models—tiny replicas that fit in your hand. That might sound sufficient, except for one problem: at that scale, you can’t capture what actually happens in the transonic region.

This is the messy zone between subsonic and supersonic flight, where shockwaves form, interact, and do unpredictable things. To really understand what’s going on, you need large-scale testing to see how those shockwaves behave. Sweden didn’t have that capability. So they built one. SAAB, with government backing, constructed its own transonic wind tunnel at Linköping. But even that wasn’t enough.

The team needed confirmation from multiple facilities, running different tests, to be certain the math wasn’t lying to them. They asked the National Aeronautical Research Establishment and the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm to check their homework. They even sent models across the Atlantic to NASA’s wind tunnels at Langley and Ames.

Data came back in big thick reports—pages filled with pressure distributions, flow separations, drag coefficients at various Mach numbers. All fascinating stuff. But just to be sure the numbers added up, SAAB’s engineers fed equations into the company’s in-house computers and the government-owned BESK machine in Stockholm—one of the fastest computers in the world in the early fifties.

BESK was a vacuum-tube monster that filled an entire room and consumed enough electricity to heat a small town. And with all that power it could churn through aerodynamic calculations, structural loads, and performance predictions at speeds that seemed miraculous compared to the slide rules and electromechanical computers that had been used to design everything from the Spitfire to the B-29.

The output came on punched cards and printouts—reams of data that Bratt’s team pored over, searching for weaknesses, checking assumptions, making sure nothing had been missed, if they’d missed something in the equations or misread the wind tunnel data—they wouldn’t know until a test pilot tried to land the thing. And by then, it might be too late.

Then came the full-scale torture tests. Wind tunnels are clean, controlled environments. Real aircraft operate in turbulent air, pull high-G maneuvers, and experience vibrations that no wind tunnel could fully replicate. So what did they do? They constructed a 30-foot diameter Ferris-wheel rig to test the fuel system under simulated flight conditions.

With this contraption, they could spin full-size fuel tanks and their components to replicate the g-forces, vibrations and the violence of combat maneuvering. All of this testing was vital. Fuel slosh in high-G turns and sudden directional changes would shift the center of gravity mid-maneuver, making the aircraft uncontrollable.

The Ferris wheel told them where to put baffles, how to design the tank structure, and which pump configurations would survive operational stresses. Since Draken was expected to intercept Soviet bombers above 50,000 feet—and possibly as high as 60–65,000 feet—they built a climatic chamber that could test structural components at temperature extremes down to -70°C and simulated altitudes up to 98,000 feet.

Swedish winters are cold, but not that cold. They needed to know what happened when metal contracted beyond anything nature could throw at it. They needed to know when hydraulic fluid thickened. When seals became brittle. When electronic components stopped working.

Every component—every rivet, every seal, every wire—had to survive those conditions without failing. They even fired frozen chickens at supersonic speeds into cockpit windscreens. A solid windscreen is important, Bird strikes at 1,000mph weren’t much fun for the pilot or the bird. Colliding with a one-kilo seagull at Mach 1.4 hits with roughly 90 000 joules — about the same as forty rifle rounds arriving at once.

The results of these test were….messy. Some windscreens shattered. Others cracked but held. With this data they were able to build windscreens that could survive a direct bird strike. Those chickens served their country well. But before Sweden invested even more enormous sums and manpower into the program they needed to know if the double-delta would actually fly. The unknowns were enormous.

There was no computer with enough power to simulate the configuration and give them a definitive answer. The design had thus far relied on wind tunnels, remote controlled models, water tanks and whatever the giant BESK computer had calculated. The data suggested the double-delta would work. But “suggested” wasn’t good enough.

Bratt’s team knew they couldn’t jump straight to a full-size prototype. The risk was too high. So in May 1950—early in the design stages, just around when Project 1220 had been ditched in favour of the double-delta—they made a decision. One that English Electric would emulate a few years later. SAAB would build a scaled-down aircraft Lilldraken would be a flying laboratory.

Its sole purpose was to prove that a double-delta winged aircraft could fly and fly well. The radical wing concept was about to face its first real-world test. If it flew, Sweden would have its interceptor. If it failed—there was no Plan B. Chapter 3: SAAB J35 Draken – Little Dragon Twenty months.

That’s how long SAAB gave themselves to take their scaled-down machine—the SAAB 210, nicknamed Lilldraken—from rubber stamp to first flight. SAAB had to move fast because they didn’t have the luxury of time, Soviet bomber technology wasn’t standing still. Every month of delay meant another month when Swedish airspace could only be defended by the ageing J 29 Tunnan—a perfectly competent subsonic fighter that would be hopelessly outclassed by whatever the Reds were developing next.

In 1951, the F-100 Super Sabre, America’s first true supersonic fighter, was still on the drawing board, and the British English Electric Lightning wouldn’t fly as the P.1 until 1954. I say this so we can appreciate the scale of the challenge Erik Bratt and his team of about ten engineers were facing.

This was an all-hands-to-the-pumps project, with many being pulled off other work because Lilldraken was now the highest priority in the building. The construction itself followed conventional stressed-skin principles—aluminium sheet over internal frames, with the fuselage and inner wing built as one integrated structure. Beyond the wing itself, the nose intake configuration was an interesting choice.

These were two oval-shaped ducts separated in the middle by a small nosecone in the form of a pyramid that was later changed to a chisel shape. Some of the details got creative out of necessity, though.

They borrowed an ejection seat from the old J 21, which ended up dictating the entire cockpit layout. The canopy was detachable—pull a handle and the whole thing would blow off if the pilot needed to get out in a hurry. Whilst researching this story, I had to translate a lot of documents from the original Swedish, and for some reason the Swedish word katapultstol, which literally translates to Catapult Seat, made me laugh out loud.

It sounds like something from a medieval siege weapon. The landing gear was only half-retractable, with no doors and no complex mechanisms—hydraulics pulled it up, gravity dropped it back down, elegantly simple and perfectly adequate for what was essentially a flying test rig.

For the engine, SAAB chose the Armstrong Siddeley Adder—a British turbojet that squeezed out all of 1,050 pounds of thrust at sea level, which is engineer-speak for “just enough to get it into the air.” But that was precisely the point. Lilldraken wasn’t meant to break speed records or reach anywhere near supersonic speeds—it just needed enough thrust to get the machine to around 370 miles an hour.

It was meant to prove that a double-delta wing could handle low-speed flight without becoming uncontrollable, and for that mission, the modest Adder was adequate. And it’s not that the Lilldraken was a large machine—just a little over six metres long from nose to tail and a wingspan of four point eight metres, half the length and width of the future J35.

The little aircraft could fit comfortably inside a typical suburban American two-car garage One particularly clever addition was the trim tank system. Since nobody knew exactly where the centre of pressure would end up across the flight envelope, they installed two tanks—one forward, one aft—filled with a water-glycol mixture. If Lilldraken started behaving oddly at a certain speed or angle of attack, the pilot could pump the liquid between tanks mid-flight, shifting the aircraft’s centre of gravity on command, literally move the aircraft’s balance point and see if that helped.

The system was later replaced with swappable weights that could be changed on the ground. By February 1951, the design of the 210 was finalised and sent to SAAB’s experimental workshop—a specialised facility where the prototypes were built. From here construction moved quickly, and by early November, Lilldraken was ready for engine runs and taxi tests.

And that’s when the problems started showing up, as they always do when theory meets hardware. During initial ground testing, the control servos—hydraulic actuators that moved the elevons—began vibrating violently at certain engine speeds. This hadn’t happened during bench tests running off an external hydraulic pump, which baffled everyone until someone realised what was different.

The external pump’s long connecting hose had been dampening pressure spikes in the hydraulic lines. Remove that hose, connect everything internally using shorter lines, and suddenly the servos were shaking themselves apart.

The solution? Run an eight-metre hydraulic hose inside the wing between the pump and the servos, replicating the damping effect they’d accidentally discovered. For the first taxi tests, Bengt Olow, SAAB’s Chief Test Pilot, was in the cockpit. These runs were naturally cautious—no point being too keen when you’re testing a new configuration. They just rolled down the runway at modest speeds, testing brakes, steering, and control response.

Olow reported that Lilldraken seemed to track straight, the directional stability appeared solid, and the controls felt light—maybe even too light—but there was no immediate cause for alarm. On one high-speed taxi trial, Olow pushed the throttle forward until the aircraft reached around 110 mph, and that’s when the aircraft began to feel light on its wheels.

Not a pitch-up, not an attempted takeoff, just that subtle weightlessness anyone who has piloted an aircraft will understand—that moment right before lift-off when the wings are generating enough lift to take the weight off the landing gear.

Which raised the obvious question: should they let it fly? The problem was the weather. December in Sweden meant short days, long nights, and snowstorms that could shut down flying for weeks. The test team had a narrow window, and they were losing daylight with every delay, so they kept doing high-speed taxi runs and waited to see what happened. What happened were unintentional hops—Lilldraken lifting a metre or two off the runway before settling back down.

Brief, moments of flight that proved the wing generated lift but told them nothing about how the aircraft actually. Then winter properly arrived. Weeks passed while Lilldraken sat in its hangar and the SAAB team waited for weather that would finally let them fly the thing properly. January 21, 1952. Clear skies and light winds over Linköping—the kind of winter morning Swedish test pilots dream about.

Olow climbed into Lilldraken’s cramped cockpit—this time, not for another taxi run, but for the real thing. He worked through the checklist methodically: Hydraulics, green and holding. Controls, full and free, Fuel, pumps on, flow confirmed. He lit the Adder, let it spool up, and taxied to the runway threshold. One last check. Temperatures and pressures in the green. Once he was happy, feet off the brakes.

Olow opened the throttle and Lilldraken began to accelerate down the runway. At about 110 miles per hour, he eased the stick back. The nose came up, and the wheels left the tarmac, and lildraken climbed into that clear blue Swedish sky. For the next twenty-five minutes, Olow flew conservative circuits, just gentle turns, checking basic control response and general behaviour to make sure the aircraft wasn’t hiding any nasty surprises.

So far, everything was working exactly as predicted. Then came the landing. Landing a delta wing requires a high angle of attack—the nose pitched up so far that forward visibility disappears completely. Olow had practised this mentally, but doing it for real in an aircraft nobody had ever landed before was another thing entirely.

He opted for a long, shallow approach—essentially a fast, flat glide that minimised angle of attack but consumed a lot of runway. Touchdown came at around 120 mph with no flare—just a gentle settling onto the wheels. Lilldraken rolled to a stop. Everyone at SAAB could breathe again. Actually, there’s an amusing footnote here.

Back in early December 1951—weeks before the actual first flight—SAAB made an odd announcement to the press, claiming that their experimental aircraft had completed its first flight, even though it hadn’t actually technically flown yet except for a few hops. Perhaps someone in the publicity department got a bit overexcited, or perhaps they were just getting their press releases ready a touch too early.

The name “Draken,” which means “The Kite” as well as “The Dragon” in Swedish, came from the wing’s shape rather than any fire-breathing beasts of yore and as dramatic as the name sounds. It was said that Erik Bratt wasn’t particularly fond of the name, but regardless, the double-delta could fly, and that simple fact changed everything.

Draken programme now had its proof of concept, and within months, the Swedish Air Force ordered three full-scale prototypes. But Lilldraken’s work was far from finished. Early flights had shown that the nose-mounted air intakes—originally chosen for aerodynamic cleanliness—weren’t providing sufficient airflow to the Adder engine. At certain speeds and angles of attack, the intake was essentially starving the engine of air.

SAAB’s solution was straightforward enough: relocate the intakes to the sides of the fuselage, just aft of the cockpit. The modification worked beautifully. Airflow improved, the engine ran properly across the flight envelope, and the side-intake configuration became the definitive layout for every Draken that followed.

Over the next four and a half years, the redesignated 210B as it was now called, would fly test after test. Sources vary on the exact numbers—some cite 887 test flights clocking up 286 hours in the air, others reference over 1,000 flights—but what matters is that the little aircraft spent years proving the double-delta concept in every configuration SAAB could think to test.

Some tests were routine enough: stability checks, control response, stall characteristics at different speeds and centre-of-gravity positions. Others were decidedly less routine. They glued wool tufts all over the wing—hundreds of them, each one a tiny wind indicator—and mounted a camera on the fin to photograph airflow patterns.

Pilots would then fly specific profiles while narrating observations into a tape recorder, calling out speeds, attitudes, and such like, dictating as much detail as possible for the engineers back on the ground. At one point, they even tested adding a horizontal stabiliser. Remember General Jacobsson back in Chapter 2—the one who insisted Draken should have a tail? SAAB humoured him with characteristic Swedish politeness. They designed a tail, built a model, and tested it thoroughly.

The results were unambiguous: adding a horizontal stabiliser made everything worse. Those powerful vortices coming off the leading edge—responsible for so much lift at high angles of attack —would hit the stabiliser and collapse. And once the vortices collapsed, the wing lost lift and the controls lost authority.

It was clear that Draken would remain tailless. Jacobsson’s intuition—well-meaning as it was—was wrong. But perhaps the most dramatic discovery came during testing in early 1953. Test pilot Olle Klinker was conducting a routine envelope-expansion test—flying slower and slower with an increase in angle of attack to find the stall boundary.

Around 80 mph with the nose pitched up to around 25 degrees, something unexpected happened. The nose snapped upward—violently—to nearly vertical. Then it fell through just as sharply. The aircraft began oscillating nose-high, nose-low, in a pendulum motion, rotating slowly left, descending rapidly—and none of Klinker’s control inputs made any difference whatsoever.

Lilldraken had just entered a superstall. Many deltas don’t stall violently—they just stop flying. Instead of spinning, they sink like a dropped manhole cover. Lilldraken was no exception. It didn’t depart; it simply fell—stable, predictable, unresponsive, and absolutely terrifying. Klinker tried everything. Full forward stick—no effect. Full aft—nothing.

Throttle adjustments only changed the rate of oscillation. Altitude bled away. 3,000 feet. 2,000 feet. 1,000 feet. Klinker reached for the ejection seat handle. Then, during one forward swing, the airspeed ticked up just enough for the elevons to bite the airflow again. He snapped the stick forward, broke the stall, and pulled out with barely 300 feet to spare.

Lilldraken wasn’t the first aircraft to fall into a superstall — but it was the first tailless double-delta to do it and live to tell the tale, thanks to a mix of luck and exceptional pilot skill, years before the term “superstall” was even coined. Back on the ground, engineers pored over the data and derived the recovery technique: stick full aft, then snap it full forward during the forward swing to break the stall before the aircraft pitches up again. It would later become standard Draken training.

What has always impressed me about this incident is how Klinker kept his head clear enough to recognise that brief moment when recovery became possible—most pilots would likely have already pulled the ejection handle. But at the time, it was simply another aerodynamic oddity—something to avoid rather than a manoeuvre that would one day make a Soviet test pilot famous.

Lilldraken kept flying through 1953, and all the way into 1956—long after the full-scale Draken had already flown. The final flight was flown on October 25, 1956, by Ceylon Utterborn, just a routine test hop, nothing as dramatic as Klinker’s flight a few years earlier.

Today, Lilldraken sits in the Swedish Air Force Museum at Linköping—slightly battered, missing its engine, sporting dummy weapons it never carried. But it had done its job. It proved the double-delta worked. It gave SAAB the confidence to build a full-size interceptor around a radical wing configuration that existed nowhere else in the world. Now it was time to build the actual Draken.

Chapter 4: SAAB J35 Draken – Stordraken October 25, 1955. Three and a half years after Lilldraken proved the double-delta concept would work, Bengt Olow found himself climbing into another prototype aircraft at Linköping. But this time, there was nothing “lil'” about it. The prototype sitting on the tarmac designated Fpl 35-1, though everyone was already calling it *Stordraken* The Big Kite was a proper interceptor.

Longer, heavier, faster, and powered by an engine that could actually generate meaningful thrust. Wingspan was just under ten metres, or 9.42 metres to be precise, nearly double the 210. Wing area came to 49 square metres, roughly half the area of a tennis court. Length? 15.35 metres nose to tail.

Olow had flown the little 210 dozens of times, understood its quirks, and knew exactly how the double-delta behaved across the flight envelope. That experience was no doubt reassuring. To a point, anyway. But the full-scale Draken wasn’t just a bigger Lilldraken. It was an entirely different proposition: eight tonnes of aluminium, fuel, and a single turbojet, all wrapped around that radical wing configuration that nobody had ever flown at this size before.

The maths said it would work. Lilldraken said it would work. Now Olow would find out if they were both right. That day. sat in the cockpit, he worked through the pre-flight checklist methodically, going through the same ritual. Controls responsive, hydraulics pressurised, fuel balanced, instruments green and reading normally.

Olow signalled the ground crew, released the brakes, and taxied to the threshold. Maybe a quiet word with the Gods then, feet off the brakes. Throttle forward. The engine spooled up and Draken accelerated down the runway.

At around 150 mph, Olow eased the stick back, the nose lifted cleanly, and moments later the main wheels left the ground. No drama, no unexpected pitch-up, just a smooth, predictable climb into the clear Swedish sky. For the next thirty minutes, Olow once again flew conservatively, like he did with the 210 on its maiden flight. Gentle turns and checking the basic controls and systems.

Making sure that the full-scale aircraft behaved as predicted, that scaling up from the smaller Lilldraken hadn’t created any nasty aerodynamic surprises. The wind tunnel data and Lilldraken’s test programme had both been vindicated. The double-delta worked at full scale, and that simple fact made all the previous years of development worthwhile.

Landing needed the same angle of attack as Lilldraken, using a long, shallow approach that ate up half the runway but kept the nose relatively level. Touchdown came smoothly at around 124 mph. Draken rolled to a stop. SAAB’s engineers, who must have been holding their collective breaths, finally relaxed. From that point, the initial test programme focused on proving the aircraft wouldn’t kill anyone, which seemed a reasonable starting point.

But once the basic handling was sorted, performance testing began in earnest. Exact climb figures for the prototypes aren’t available, but the first production J 35A variants give us a clue. The official service ceiling was rated at 49,000 feet, but in practice the aircraft was only reaching around 42,000 feet—which wasn’t quite enough to reliably intercept threats operating at maximum altitude.

It was clear though that the engineers had certainly built a fine machine and the airframe had plenty of potential, but it would need more powerful engines to reach where Soviet bombers would actually be flying. Bigger engines would indeed come. Swedish doctrine assumed dispersed highway bases and conscript mechanics with basic tools, the fuselage had been built in two sections, forward and rear, bolted together at midsection.

Therefore, in the event the engine had to be changed, they simply unbolted the rear fuselage, slid the engine out backwards, swapped it, and bolted everything back together. The outer wing sections detached just as easily for transport. Maybe this is where Ikea got their ideas from.

Here’s something for all the hardcore aviation nerds, even the hydraulic system did not escape SAAB’s obsession with reducing weight. Pressurized at 210 kilograms per square centimeter, it was more than double the pressure in the earlier J 29, why is this number significant Well, simply put, Higher pressure meant smaller hardware. Double the pressure and you only need half the piston area to generate the same force.

Smaller pistons meant smaller actuators, slimmer plumbing, and a modest reduction in the volume of hydraulic fluid sloshing around the airframe. In an aircraft where every kilogram had to earn its keep, that was weight SAAB could reallocate to things that actually mattered: fuel, weapons, and structure.

The controls were fully powered, which is great, but fully powered controls don’t provide any natural feedback, meaning the pilots had no tactile sense of aerodynamic loading. Pull the stick in a conventional fighter and you feel resistance. In Draken, you felt nothing. SAAB therefore installed a q-feel system.

Artificial generators that faked aerodynamic forces on the stick based on dynamic pressure. Not perfect, but it prevented pilots from over-controlling at high speed. Which was the important bit. But whilst that first flight was a big win for the airframe design, getting to that point meant overcoming a problem that had nearly derailed the entire programme before 35-1 even left the ground, and the source of that problem was the engine.

The Svenska Flygmotor RM 5A sitting in the prototype rear fuselage was the end of a dream and the beginning of a compromise that Swedish engineers had spent years trying to avoid. Though I should note—while researching this story, some sources claimed the prototype was actually powered by a Rolls-Royce Avon that SAAB had borrowed directly from the British rather than a license-built RM 5A.

The documentation isn’t entirely clear on this point, but either way, the engine itself represented the same compromise. Sweden had never wanted to rely on foreign engines. The plan, ambitious but logical for a country with Sweden’s technical expertise, had been to develop indigenous turbojets that could power everything from Lansen aircraft to the supersonic Draken interceptor.

Two companies were competing for the work: Svenska Flygmotor with their centrifugal designs, and STAL with their more sophisticated axial-flow engines. By mid-1949, the Air Board had made its choice. STAL’s axial design, specifically the Dovern turbojet, would power Lansen. And the even more powerful Glan, still on the drawing board, would propel Draken to Mach 2.

Dovern took years of development work and was to be the source of considerable national pride. Chief designer Curt Nicolin and his team at STAL’s facility had created a sophisticated engine with a nine-stage axial compressor that fed nine combustion chambers and a single-stage turbine. With help from the British they were able to fill the component gaps, such as fitting Lucas fuel controls, Nimonic flame tubes and Jessop steel turbine discs.

But, it can’t be stressed enough, the overall design was Swedish. By comparison, the British Avon followed a noticeably different design philosophy. While the engineers at STAL focused on compactness, the Avon had a far more elaborate multi-stage axial compressor and a more refined cannular burner system to reach higher pressure ratios and greater thrust.

In effect, Britain was pushing for maximum performance through complexity, whereas Sweden pursued efficiency and manufacturability through elegant simplicity. The two engines shared broad principles, but diverged sharply in execution. But, having said all that, the Dovern worked. Eventually. Getting there required solving problems that would’ve killed lesser programmes.

To give you an idea of the problems they faced, during bench testing, turbine blades would snap off due to resonance vibration, which meant time and resources to redesign them with more rigidity. Then the turbine bearings failed, which needed additional modifications to the cooling and lubrication system.

The changes mounted into the thousands, literally thousands, as engineers discovered that solving one issue inevitably revealed another. Compressor surging, blow-off valve timing, combustor flame stability, all the problems that Stanley Hooker and his team had already experienced. Each problem got catalogued, analysed, and eventually solved, though never as quickly as the programme managers would have liked.

But finally, by July 1952, Dovern was finally ready for flight testing. And to do this, SAAB borrowed an Avro Lancaster redesignated Tp-80 in Swedish Service, and mounted the turbojet in a streamlined nacelle beneath the fuselage. The engine ran beautifully over three hundred hours of flight testing and four thousand total hours including bench runs.

Dovern was producing approximately 7,300 pounds of thrust at 7,200 rpm. Glan, intended for Draken, had reached the component manufacture stage and was projected to deliver around 11,000 pounds of thrust dry, and over 15,000 with afterburner. Sweden was on the verge of joining the very exclusive club of nations that could design, build, and produce their own high-performance turbojet engines. More importantly, they’d be in control of their own destiny.

No waiting for export licences, no dependency on foreign suppliers, no compromises forced by someone else’s strategic priorities. It all looked like it was coming together, until in November 1952, when everything stopped. Completely. The decision had came from the top. Both Dovern and Glan were to be cancelled immediately with no phased shutdown, no transition period.

Just dead programmes and thousands of hours of development work consigned to history. The reason? Well, Rolls-Royce had made an offer the Swedes couldn’t refuse. The timing was perfect, from Rolls-Royce’s perspective. Britain needed export sales to justify continued Avon development, and Sweden needed proven engines whilst haemorrhaging money trying to develop its own.

The offer was to be fair, quite generous, it included licensing rights for the entire Avon family, extremely favourable financial terms, and crucially full access to future Avon developments. For the Swedish government, the maths was brutally clear. Indigenous engine development had become unsustainably expensive.

The population of Sweden remained smaller than London or New York, which meant the tax base couldn’t support the kind of long-term investment that turbojets demanded. And whilst Dovern had finally been sorted after years of problems, the Avon had already accumulated thirty thousand flight hours and was proven, reliable, and available now. Svenska Flygmotor would build Avons under licence. But STAL’s turbojet work would end, the Glan would never run, and Dovern would never power an operational aircraft.

Swedish engineers took it about as well as you’d expect. The decision left SAAB in an awkward position. Lansen had been designed around Dovern and now needed redesigning around the Avon RM6. Draken, which hadn’t even flown yet, would have to use British engines from the start.

The very thing the entire indigenous engine programme had been meant to avoid. But there was a silver lining, though it would take a while to become apparent. The Avon was a fundamentally better engine than anything Sweden could’ve developed on its budget.

More thrust, better fuel consumption, easier maintenance, and (most importantly) Rolls-Royce’s engineering team had already solved most of the problems that would’ve plagued Swedish engines for years. Still, using British engines stung, especially when Svenska Flygmotor engineers started developing their own afterburners to mate with the licence-built Avons, which led to a whole new set of problems.

Just as Sweden’s engine ambitions were collapsing, the airframe itself was proving everything the wind tunnel models had promised. The problem now was making everything else around it work too. The first production Drakens, designated J 35A, with the Swedish military’s typical flair for memorable names came with the RM6B engine and a Swedish-designed afterburner called the EBK 65.

Sixty-five aircraft got this configuration, officially known as the J 35A1, though pilots and ground crews called them *Adam kort, Adam short for reasons that would soon become painfully obvious. With the EBK 65 fitted, the engine could now push out 15,000 pounds of thrust with the afterburner lit, which was respectable.

The whole engine assembly was relatively compact, that meant the rear fuselage could be kept short. This created a problem during landing. Remember, delta wings require high angle of attack for landing. Sometimes twelve to fifteen degrees nose-up. At that attitude, with a short tail, the rear fuselage was uncomfortably close to the tarmac.

SAAB’s solution was pragmatic: fit a small solid tailskid to protect the underside during landing. The tailskid did its job, technically. It prevented structural damage. It also left a spectacular trail of sparks down the runway every time a pilot misjudged the flare, which was both impressive and mildly concerning for everyone watching.

The improved EBK 66 afterburner addressed this whilst adding about 600-700 pounds more thrust, excellent news for performance. Unfortunately, it was also longer. Significantly longer, long enough that fitting it into the existing rear fuselage wasn’t possible without extending the entire tail section. So the last twenty-five J 35As, the *Adam lång*, or Adam long got a lengthened rear fuselage to accommodate the more powerful afterburner.

This meant replacing the tailskid with something more sophisticated. SAAB’s engineers came up with a brilliantly simple solution: a set of retractable double tail wheels, quickly nicknamed “roller-skate wheels.” The wheels retracted into the lengthened tail during flight and deployed automatically during landing, meaning pilots could use the full nose-high attitude for maximum aerodynamic braking without turning the rear fuselage into a grinding stone. As a bonus, the longer tail unexpectedly

reduced drag, which meant the EBK 66 aircraft were not only more powerful but also slightly more efficient. Sometimes engineering problems solve themselves, after a fashion. Whilst SAAB was sorting afterburners and tail lengths, the prototype flight test programme was running into problems of its own.

The second prototype Fpl 35-2 flew for the first time in March 1956. Unlike the cautious 35-1, which had flown without an afterburner, the second prototype carried a more powerful Avon Mark 46 and an operational afterburner from day one. The test pilot lit it during the climb. And accidentally broke the sound barrier.

On the first flight. Whilst climbing. The aircraft handled it without drama, and showed just how much thrust the afterburning Avon could produce when given the beans. But having said that, two months earlier, on 26 January 1956, prototype 35-1 had already exceeded Mach 1.

0 in level flight using an uprated Avon Mark 43 engine with no afterburner. This proved something fundamental about the double-delta design. Supersonic flight was possible even without lighting the afterburner, which meant the wing’s low drag characteristics were as good as the wind tunnel data had promised.

For an aircraft designed with slide rules and wind tunnels and primitive computers, that was validation of Erik Bratt’s fundamental aerodynamic concept. However, the celebrations didn’t last long. A week after 35-2’s accidental supersonic flight, the accidents began. During the landing roll at Linköping, Bengt Olow accidentally mixed up the controls—retracting the landing gear instead of deploying the brake parachute.

The gear folded up and the aircraft dropped onto its belly. Fortunately Olow was unharmed, but 35-2, unofficially nicknamed “Gamla Mormor,” Old Grandmother, needed many months in the hangar for significant repairs. And then a month later, prototype 35-1 belly-landed too.

On 19 April 1956, test pilot K-E Fernberg was on final approach for landing when he hit the switch to lower the gear. But there was a problem, the undercarriage indicator lights showed nothing, no green “down and locked,” no red warnings either, he tried again, cycling the gear up and down, still nothing and so after trying whatever he could, he reluctantly came in for a belly landing.

Fernberg executed it perfectly, despite landing on the wrong side of the main runway, the aircraft slid across the tarmac that as you can imagine caused a lot of damage to the underside. Fernberg for his efforts suffered a minor back injury. However, interestingly, the post crash tests on the landing gear mechanism showed that it worked without any issues.

What the available records don’t make entirely clear is whether the gear had actually extended and locked during the landing and Fernberg couldn’t confirm it and the gear folded or whether the indicator failure hid an actual malfunction What is clear is that SAAB had just lost months of testing. With two of the three prototypes out of action SAAB’s test programme was, to use the technical term, completely stuffed.

Worse, the Air Board was watching. Two belly landings in such a short time, Fingers were crossed that the third prototype would not suffer the same fate. The third prototype in fact saved the programme. Fpl 35-3 made its first flight in September 1956, later than planned, but perfectly timed to take over testing duties whilst 35-1 and 35-2 were being rebuilt.

This third aircraft was different from its predecessors: it was the first prototype fitted with cannon armament, which meant SAAB could finally start weapons testing alongside the aerodynamic work. By early 1957, SAAB had all three prototypes flying, with pilots and engineers trying to find all the inevitable problems that come with any new design.

Some of these problems were minor. Others were decidedly less so. Control sensitivity became apparent almost immediately. Draken was touchy around the pitch axis, far more sensitive than Lilldraken had been. The combination of a tailless layout and highly swept wing meant the elevons, positioned far aft on the wing trailing edge, had tremendous leverage for pitch control.

Small stick inputs produced large nose movements, which led to pilot-induced oscillations during approach and landing. Some pilots reportedly claimed, only half-joking, that the oscillations could be set off by their heartbeat. This wasn’t just annoying. It was dangerous. Several crashes resulted from pilots over-controlling the aircraft during critical phases of flight.

SAAB’s solution involved retrofitting less sensitive flight control systems to early aircraft, which helped but didn’t entirely eliminate the problem. Draken would always demand smooth, precise inputs. Pilots who tried to muscle her around like a conventional fighter quickly discovered why that was a bad idea. Landing brought its own challenges.

Pilot Bosse Engberg, who transitioned to Draken from conventional trainers, described the adjustment: “Coming from a trainer with nose-down during approach, the high angle of attack was a new experience. Raising the nose immediately required more thrust. Also, the fact that you had to look somewhat sideways around the instrument panel to see the runway was initially an awkward feeling.

” But perhaps the most insidious problem involved the flight controls themselves at high speed and low altitude. During high-speed manoeuvring, particularly at transonic speeds near sea level, pilots discovered something unpleasant. Pull hard on the stick, and not much happened. The elevons deflected, but not fully.

The problem was that the hydraulic actuators simply weren’t powerful enough to produce full control surface movement against the massive aerodynamic loads at high dynamic pressure. SAAB called this “servo stall,” though that term somewhat understated the problem. If your hydraulics can’t move your control surfaces during high-G manoeuvres at low altitude, you’ve got an aircraft that can’t pull out of dives when you need it most. Not exactly confidence-inspiring. The fix was clever but symptomatic

of the compromises inherent in the tailless delta design. SAAB modified the flight control system so that when the pilot pulled more than 13 pounds of force on the stick, the upper airbrakes would automatically deploy as manoeuvring flaps. This increased the nose-up pitching moment, helping the pilot pull the aircraft through high-G turns even when the elevons were reaching their deflection limits.

It worked, after a fashion. But it also meant Draken’s sustained turn performance was never going to match aircraft with conventional tail surfaces. The delta wing generated tremendous amounts of lift in tight turns when the nose was pitched up high, but also tremendous amounts of drag.

Think of it like using a barn door as an airbrake. The wing was presenting a huge surface area to the airflow, slowing the aircraft down rapidly. Energy bled off rapidly, and maintaining airspeed during tight manoeuvres required all available thrust. Sometimes even that wasn’t enough. This wasn’t a flaw, exactly. It was the inevitable trade-off of designing an aircraft optimised for high-speed interception rather than dogfighting.

Draken was meant to climb fast, accelerate to high supersonic speeds, and destroy Soviet bombers. For that mission, the limitations were acceptable. In later years, Draken variants — especially the J 35D and successors — pushed performance into the Mach-2 class, with service ceilings around 65,000 ft. We’ll cover the later variants in part 2 of Draken’s story.

Some online sources I have seen claimed that compared to typical figures for the Mirage III, Draken had superior climb performance under certain clean or optimal conditions. For instance, when the Swiss put Draken head-to-head against the Dassault Mirage III in evaluation trials, Draken’s climb rate turned out 20–40% superior.

For context, that’s the difference between ‘we might catch them’ and ‘we will catch them.’ Let me know what you think in the comments. Even though prototype testing would continue it was time for Draken to go to work as an operational interceptor and find out if the Dragon could defend Sweden from the Bear. By 1960, Sweden had their supersonic interceptor, they’d done what many had thought impossible, a country with a tiny population compared to Russia, USA and even Britain had built what would become a legendary aircraft. The prototypes proved the aircraft worked,

but Swedish engineers weren’t yet finished, not by a long shot.