May 1944, a Mustang screams down at 700 ft per second toward a German convoy. The dive angle is 60°. Control surfaces shudder. The airframe groans. Every pilot in the squadron has been told this maneuver will kill you. But Lieutenant Robert Strobble isn’t pulling up. He’s counting rivets on the canvas of supply trucks growing larger in his gun site.

In 18 seconds, he will either prove the impossible or become another name on the missing air crew list. Northern France breathes differently under occupation. The hedros blur green and gray. Villages crouch silent beneath church steeples that no longer ring bells at noon. Roads carry vermached supply columns day and night feeding the Atlantic wall fortifications that stretch from Belgium to Britany.

Every gallon of fuel, every crate of ammunition, every replacement uniform travels these narrow arteries between railheads and frontline depots. Allied fighter bombers hunt them relentlessly. Thunderbolts and typhoons strafe convoys at shallow angles, raking trucks with 50 caliber rounds and rockets. But the math is brutal.

A fighter approaching at 15° sees its target for maybe 3 seconds. Deflection changes constantly. Bullets spray wide. Most passes score hits on one, maybe two vehicles before the pilot must pull away to avoid ground collision or flack concentration. German logistics officers know this. They space convoys. They move at dawn and dusk when light plays tricks.

They position flack wagons every fifth vehicle. Quadmounted 20s that can shred an aircraft in a single burst. The convoys bleed, but they keep moving. Panzer divisions in Normandy keep fighting. The Eighth Air Force needs those trucks stopped. Not damaged, stopped, burning, blocking the roads so nothing behind them can pass.

Higher command issues emphatic guidance. Destroy transportation networks, cut the enemy’s tendons. But no one explains how a pilot is supposed to do that when doctrine, physics, and survival instinct all say the same thing. Stay shallow, stay fast, stay alive. If this history matters to you, tap like and subscribe.

Robert Strobel grew up in Ohio farm country where angles mattered. His father ran a grain operation outside Toledo. Every autumn meant calculating hopper trajectories, adjusting combine blades, understanding how speed and descent affected yield. Nothing abstract, just geometry. you could see in falling wheat and dust patterns.

He was 22 when he enlisted, slender build, quiet voice, the kind of young man who listened more than he spoke and noticed things others dismissed as irrelevant. Flight school instructors noted his smooth hands on the stick, his uncanny ability to judge distance without instruments. He didn’t yank the Mustang through maneuvers.

He guided it, felt it. By spring of 1944, he was assigned to the 361st Fighter Group, flying top cover and bomber escort out of Bautam in eastern England. The P-51 was still new enough that pilots were learning its edges, range like nothing before it. Speed that embarrassed Luftwaffa interceptors above 20,000 ft. But down low in the weeds where ground attack happened, it was just another fighter trying not to become a fireball.

Strobel flew the standard missions. Strafe when you see opportunity. Don’t fixate. Don’t press. The pilots who pressed ended up flying into the ground or catching a flax shell through the coolant system and gliding 10 miles to a belly landing in enemy territory if they were lucky. He watched those shallow strafing runs.

He watched the gun camera footage during debriefs. Tracers walked across fields, clipped fenders, shattered windshields. Rarely did a truck explode. Rarely did a convoy stop. They just kept rolling. And the next day, another flight would hit another convoy with the same results. There had to be a better geometry.

The problem was dwell time. A fighter screaming past at 300 knots gives its guns maybe two seconds on target. At shallow angles, the bullets arrived almost horizontally, punching through thin canvas and wood, but rarely hitting engines, fuel tanks, or cargo deep inside the truck beds. Damage was superficial.

Pilots expended thousands of rounds for marginal effect. Some tried rockets, but rockets required steady flight and forward speed, making the attacking aircraft a beautiful target for German gunners who’d learned to track the contrails and hose the sky with flack. Hit rates were abysmal. A study from 9inth Air Force estimated 1 in 12 rockets struck within 20 ft of aim point.

Others advocated skip bombing, bouncing small bombs off roads into convoys. It worked against ships sometimes. Against trucks it was a gamble. Fuses had to be perfect. Approach had to be suicidally low. And German flack crews loved a predictable bomber run. Higher command considered the problem intractable. Accept the inefficiency.

Make up for it with volume. Send more sorties, expend more ammunition. The war was being won by industrial output anyway. Why risk pilots experimenting when standard tactics worked well enough? But well enough wasn’t enough. Every truck that reached the front carried bullets that would kill allied infantry. Every supply convoy that slipped through meant another day of fighting in the boage.

Another week until breakthrough. Strobel studied the angles in his head. He sketched diagrams on the back of navigation charts. If you came down steep, nearly vertical, your guns would fire almost straight into the top of the vehicle. Engines sit in front. Fuel tanks sit in the middle. Cargo sits exposed.

A steep dive gave you a stationary target picture and maximum dwell time because your rate of closure was deliberate, controlled by throttle and dive brakes if needed. But doctrine was clear. Dives steeper than 45° were for dive bombers, not fighters. The Mustang wasn’t stressed for that, or so the manuals claimed.

And even if the airframe held, the pilot would black out from G forces during pull out or simply wouldn’t have enough altitude to recover before impact. It was by every measure a suicide technique, May 17th. The morning briefing covered the usual escort bombers to Brunswick, then free hunt on the return leg.

Strobel said nothing during the briefing, but after the group commander left, he mentioned his idea to two wingmen over weak coffee in the dispersal hut. He explained the geometry, showed the sketches. One pilot laughed outright. The other just shook his head. The flight surgeon, overhearing, told him flatly that a 60° dive would put 8 G’s on him during recovery.

He’d gray out, maybe lose consciousness. Even if he stayed awake, the Mustang’s elevator authority might not be enough. He’d augur straight into French soil at terminal velocity, and they’d need a shovel to recover his dog tags. Strobel asked if anyone had actually tested it. Silence. No one had because no one was that reckless. He didn’t argue.

He just nodded and walked out to his aircraft. The crew chief was finishing the pre-flight, wiping oil from the cowling. Strobel asked him a simple question. Could the airframe handle a sustained 60° dive at combat power? The chief looked at him like he’d asked if the wings could be removed in flight. Structurally, maybe.

But why would anyone try? Strobel didn’t answer. He climbed into the cockpit and ran his checks with the same methodical calm he always did. Magnetos, trim, fuel mixture, oxygen flow. The Merlin engine coughed, caught, and settled into its smooth, rattling idle. Around him, 11 other Mustangs were starting up, blue exhaust ghosting across the tarmac in the early light.

He thought about his father adjusting the combine blades, chasing the optimal angle season after season until he got it right. Sometimes you had to test what everyone said was impossible because sometimes everyone was wrong. The mission went as planned until the return leg. Bombers struck their targets.

Luftwaffa resistance was light. A few 109s bouncing the formation over Hanover before disengaging. By early afternoon, the bomber stream was headed home and the fighters were released to ground attack. Strobel’s flight dropped down to 8,000 ft, scanning the French countryside for targets of opportunity. The radio crackled with callouts, locomotives, barges, troop columns.

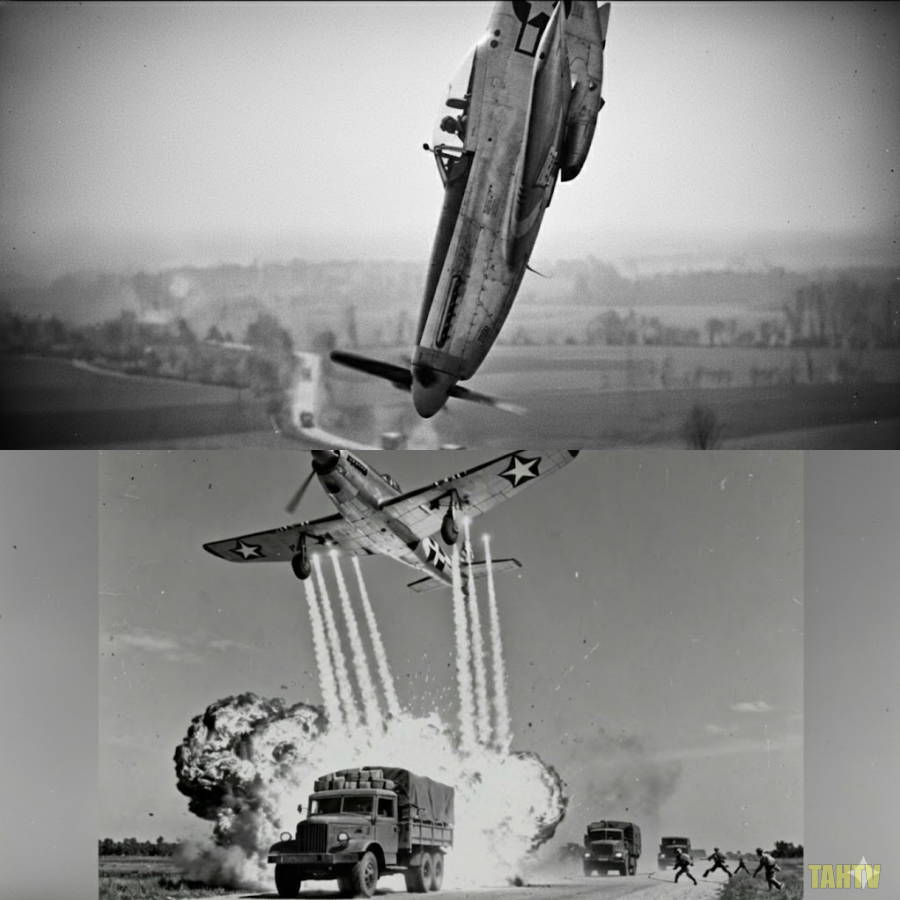

Then someone spotted it. A convoy, maybe 20 vehicles, strung along a road south of Ruon. No air cover, minimal flack evident. The flight leader called the attack. Standard approach, single pass, shallow angle, don’t press. Strobel rogered the call, but he had no intention of following it. He peeled off early, climbing another,000 ft while the rest of the flight descended into their strafing run.

From 9,500 ft, he could see the entire convoy. trucks in tight intervals, a few command cars, one flack wagon near the rear, its crew likely scanning the horizon for the fighters they could hear but not yet see. Strobel rolled inverted and pulled the nose down. 60°. The airspeed indicator climbed 300 knots. 400.

The Mustang’s nose pointed at a supply truck near the front of the column like a rifle aimed at a stationary target. He adjusted throttle, feeling the dive stabilize. No buffet, no vibration, just smooth, controlled descent. The truck grew in his gunsight. He could see the canvas cover rippling in the wind.

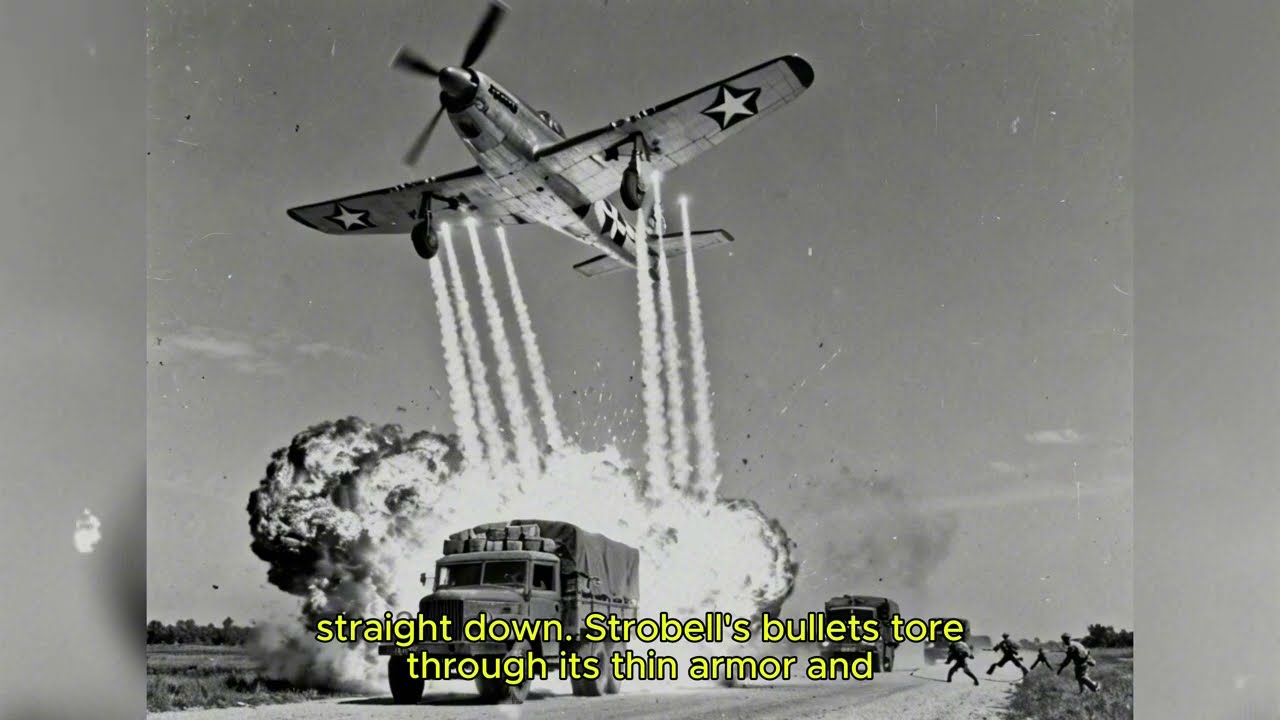

Could see the driver’s side mirror. Could see individual tire treads. His altitude unwound. 6,000 5,000. His finger rested on the trigger. At 4,000 ft, he opened fire. 650s erupted, their recoil shuttering through the airframe. Tracers poured down in an almost vertical line. He walked the rudder gently, sliding the stream across the truck’s length.

Sparks erupted from the hood. The canvas shredded. Then a flash, a bloom of orange flame, and the truck disintegrated as fuel or ammunition cooked off. He didn’t pull up. He pushed the nose forward slightly, tracking to the second vehicle. The dive angle held. Air speed bled off just enough to keep him subsonic. He fired again.

Another truck exploded, then a third. His tracers were hitting dead center every time because the target wasn’t moving relative to his gunsite. It was like shooting at a picture. Altitude 30,000. Still diving. Fourth truck. Fifth. Sixth. Explosions rippled down the convoy in sequence. The flack wagon swung its guns skyward, but couldn’t depress them enough to track something coming almost straight down.

Strobel’s bullets tore through its thin armor and it erupted in a spray of white hot fragments. Seven 8 nine. The convoy was a chain of fireballs now, trucks slamming into the wreckage ahead as drivers panicked or died at the wheel. He fired through the 11th vehicle and finally eased back on the stick. Altitude 1,800 ft.

The GeForce crushed him into his seat. Gray crept in at the edges of his vision. His arms felt like lead, but the Mustang responded. The nose came up. The horizon leveled. He bottomed out at 900 ft. Still flying, still conscious. Behind him, 12 trucks burned. The road was completely blocked. Black smoke climbed into the afternoon sky like a funeral p.

His wingmen were shouting over the radio, asking if he was alive, asking what the hell just happened. Strobel keyed the mic and told them he was fine. His voice was calm, almost casual. He climbed back to altitude and rejoined the formation for the flight home. In the gun camera footage, reviewed that evening in stunned silence, every detail was visible.

The steep dive, the precision, the methodical destruction. 12 vehicles in a single pass, no rockets, no bombs, just gravity, geometry, and six machine guns firing into the heart of each target. The squadron intelligence officer replayed it three times. Then he looked at Strobble and asked how he’d survived the pull out.

Strobel said he’d kept the speed below red line and trusted the airframe. The officer asked if he’d do it again. Strobel said he didn’t see why not. Someone in the back of the room muttered that it was still suicide, but the gun camera didn’t lie. 12 trucks, one pass, zero damage to the Mustang. The math had just changed. Within a week, three other pilots in the 361st tried the technique.

Two succeeded. One pushed too hard, pulled too late, and bent his airframe on recovery. He landed safely, but the Mustang was written off, its fuselage buckled behind the cockpit. The lesson was clear. The maneuver worked, but only within narrow parameters. Altitude discipline, speed discipline, G tolerance awareness.

Flight leaders began teaching it selectively. Not to everyone, not to the aggressive pilots who already pressed too hard, but to the smooth ones, the calculators, the ones who could hold a dive angle without fixating, who could judge pullout altitude by feel. By June, after the Normandy invasion, the technique spread across other fighter groups.

Thunderbolts and Mustangs began hitting convoys with devastating efficiency. A single flight could destroy an entire logistics column in minutes. German supply officers started moving convoys only at night, then only in small packets, then when possible, not at all. Rail traffic increased. Rail yards became target-rich environments.

The logistical strangle hold tightened. 9inth Air Force compiled data through the summer. Convoy destruction rates tripled. Ammunition expenditure per vehicle killed dropped by 40%. Pilot losses on ground attack missions fell because time over target decreased and flack crews couldn’t track the nearvertical dives effectively. No formal doctrine was ever written.

No manual ever updated. It remained a technique passed pilot to pilot, flight to flight, learned through demonstration and practice, but its effects were measurable. In August, a captured German quartermaster reported that supply shortages were crippling frontline units more than direct combat losses. Trucks weren’t reaching their destinations.

Fuel wasn’t arriving. Divisions were immobilized not by enemy tanks, but by empty jerry cans. Strobel flew 68 more combat missions. He refined the technique, experimented with different dive angles for different targets. Trains required shallower dives because they moved. Barges needed lead calculation, but trucks, stationary or slowmoving on roads, were always the same. steep, controlled, lethal.

He never promoted the method, never claimed credit. In debriefings, he described it clinically as though he were explaining crop rotation, just angles and timing, just paying attention to what worked. Other pilots called it the Strobel dive. He shrugged off the name. It wasn’t his. It was just physics that everyone had been too cautious to try. The war ended.

Strobel returned to Ohio. He never flew again. Went back to farming, took over his father’s operation, spent 40 years optimizing yields and teaching his sons the same patient geometry that had once turned a fighter into a precision instrument. He rarely spoke about the war. When pressed, he’d mention the missions in passing, the way someone might mention a previous job.

No drama, no embellishment, just a thing he’d done when it needed doing. In 1983, a military aviation historian tracked him down, asked for an interview about the dive technique that had reshaped ground attack doctrine without ever being formally recognized. Strobel agreed, but only briefly.

He explained the mechanics again, the same way he had in 1944. Angle, speed, altitude. He mentioned that most people overthink survival. Sometimes the dangerous thing is safer because no one expects it. The historian asked if he’d been afraid during that first dive. Strobel thought for a moment. Then he said fear wasn’t the right word.

Uncertainty maybe, but uncertainty was just a gap in knowledge. You tested, you learned, you adjusted. He died in 1991. No obituary mentioned the 12 trucks. No memorial listed the convoys he’d stopped or the infantry lives saved by ammunition that never arrived. He was remembered as a good farmer, a patient teacher, a man who believed problems had solutions if you looked at them from the right angle.

But in the cockpits of attack aircraft for generations afterward, the principle endured. When doctrine fails, test. When everyone says it’s impossible, check the math yourself. When survival and mission seem opposed, sometimes they’re the same thing seen from different altitudes. Strobel didn’t change warfare through brilliance or heroism in the cinematic sense.

He changed it by refusing to accept inefficiency when a better geometry existed. By trusting an airframe more than the fear surrounding it. By understanding that the most dangerous path is sometimes the one no one’s dared to walk. 12 trucks in 18 seconds. Not because he was reckless, because he was patient enough to see what panic and doctrine had obscured.

That courage isn’t the absence of danger. It’s the presence of logic when everyone else has stopped thinking. The Mustang could take the dive. The pilot could take the G’s. The enemy couldn’t take the geometry. And for a few crucial months in 1944, that equation rewrote the math of ground attack over occupied Europe, one 60deree dive at a time.