On March 31st, 1945, American troops at Frankfurt airfield watched in confusion as an unidentified aircraft circled overhead. They couldn’t tell if it was friend or enemy. The pilot was desperately trying to land a jet that wouldn’t put its landing gear down. Inside the cockpit sat a German test pilot who’d been waiting months for this exact moment, risking execution to deliver Hitler’s most advanced weapon straight into American hands.

But the wildest part of this jet story wasn’t the war itself. It was what happened after. It’s a story of how a weapon of the Third Reich became the grandfather of American air power. What if I told you this revolutionary aircraft kept flying for another six years under a completely different flag and that right now in 2024 you can still see one tier through the sky at air shows? This is the true story of what happened to the ME262 after World War II.

Let me paint the scene for you. It’s Good Friday 1945. Hans Fay, a 57year-old messes test pilot with over 11,000 flight hours, has been handed orders to ferry a factory fresh ME262 to safety before Allied forces capture it. He’s one of 22 pilots tasked with moving these jets from the assembly plant to a more secure location.

But Fay has other plans. For months, he’s been waiting for his chance to defect. The problem, his elderly parents live in a small German town, and he knows the authorities will execute them the moment he betrays the Reich. He’s trapped, sitting on the world’s most advanced aircraft, watching Germany collapse, unable to make his move.

Then word reaches him. American forces have captured his parents’ town. They’re safe. This is his moment. At 1:45 p.m. on March 31st, Fay fires up the jet engines and takes off. But immediately, something goes wrong. The landing gear won’t retract. He cycles it again and again. Nothing. The gear is stuck down. Now he’s got a critical decision.

Try to land near his hometown on a small airfield with a malfunctioning jet. or head for Frankfurt’s larger Rin Main airfield where there are actual runways and emergency equipment. He banks toward Frankfurt. Picture American troops on the ground squinting up at this strange silver aircraft with its wheels stuck down, unable to identify it.

Is it German? Is it American? Nobody knows. They’re tracking it with their weapons, fingers on triggers. Fay carefully surveys the bomb cratered airfield, picks the only usable runway strip, and brings the unpainted jet in for what military reports called a perfect landing. He climbs out of the cockpit, hands raised.

The Allied forces suddenly realize what they’re looking at. A brand new Messormidt Me 262, the world’s first operational jet fighter delivered gift wrapped with a test pilot who knows everything about it. This single aircraft designated work number 111711 would become the most tested ME262 in American history.

It would fly more test flights than any other captured example. And here’s the tragic irony. after surviving the entire war, after Hans Fay’s dramatic defection, after countless test flights. But I’m getting ahead of myself. We need to talk about what happened in those first chaotic weeks after Germany surrendered.

The moment Germany fell, a secret competition began between the Allies. This wasn’t about winning the war anymore. The war was over. This was about winning the next 50 years of aviation. Enter Colonel Harold Watson. This guy was straight out of a comic book. Literally, he wore a white silk scarf, a shiny brown leather jacket, and walked around like he owned the sky.

Years later, people would claim he was the real life inspiration for Steve Canyon, the comic book fighter pilot hero. Watson never denied it. The Army Air Forces put him in charge of Operation Lusty. Yes, that’s the real name. It stood for Luftwaffa secret technology. But come on, they knew what they were doing with that acronym.

Watson assembled a team of hot shot test pilots, engineers, and mechanics who became known as Watson’s whizzers. Their mission, fan out across Germany, find every ME262 they could, get them flyable, and ship them to America before the Soviets grabbed them. Here’s the crazy part. They were competing against 32 other Allied intelligence teams doing the exact same thing.

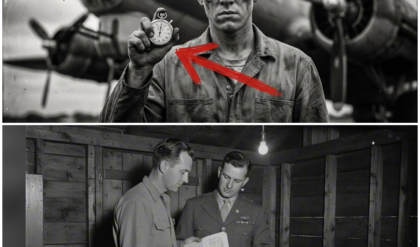

One day, Watson storms into Lieutenant Robert Strobble’s office, white scarf flowing naturally, throws some papers on his desk and barks, “This is all we know about the ME262. I want you to draw field gear and go to Lechfeld, Germany. I want you to train pilots to fly it and crew chiefs to maintain it.” Then he just spins around and leaves.

Strobel’s thinking, “Wait, what?” The next day he’s on a C47 heading to Germany. When Watson’s team reaches Lechfeld airfield outside Augsburg, they hit the jackpot. 25 relatively intact ME262s, including the holy grail, a two seat trainer. But there’s a problem. These jets have been bombed.

sabotaged and booby trapped. The team discovers explosive devices hidden in cockpits. GIs are so eager to examine the aircraft that they accidentally tear the nose gear off one jet while trying to tow it. And nobody nobody on the American side knows how to fly these things. So they make a deal with the enemy.

Two German test pilots agree to help. Ludvig Hoffman, nicknamed Willie, and Carl Bower, called Pete, Messesmidt’s chief test pilot. These are the guys who taught Luftwafa aces how to fly jets. Hoffman had even met Charles Lindberg before the war. The Americans give one of the captured jets a nickname, Vera, after the sister-in-law of Staff Sergeant Eugene Fryberger, one of the guys working on the aircraft.

On June 9th, 1945, the training begins. Get this. Watson’s pilots learned to fly the ME262 with exactly 7 minutes of in-flight instruction in the two seat Vera. Seven minutes. These are guys who’ve been flying P47 Thunderbolts, heavy rumbling propeller fighters. Now they’re about to solo in a jet for the first time. No pressure.

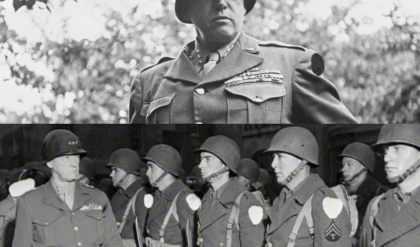

The next day, June 10th, nine ME262s line up for the ferry flight to France. For five of the American pilots, this is their first time soloing in a jet. One of them, Lieutenant Strobble, can’t resist showing off at the end of his test flight. He performs a vertical barrel roll. General Carl Tui Spats watches the demonstration.

Afterward, he turns to Watson and says, “Hal, that’s a wicked airplane. Wicked. Wicked. I’m sure glad they screwed up the tactical use.” The team even creates their own unofficial patch. Donald Duck riding a jet engine around the globe with Watson’s whizzers written underneath. They ferry the jets to Sherborg, France, where the British loan them HMS Reaper, an aircraft carrier to ship everything to America.

The jets arrive at Wrightfield in Ohio, where American engineers are about to discover something that will blow their minds. When engineers tear apart these captured ME262s, they realize something terrifying. Germany was 5 to 10 years ahead in jet technology. The swept wings, not just for looks, the wing slats, genius.

The underslung engine necessels, solving problems American designers didn’t even know existed yet. North American aviation assigns engineer Edgar Schmood to study the captured ME262 manuals. One engineer, Larry Green, literally learns German just to read the technical documents. The result, the F86 Saber, the legendary jet that would dominate Korean war skies.

Look at an F86 and an ME262 side by side. The family resemblance is unmistakable. The Soviets are doing the exact same thing on their side. Their captured ME262s become the blueprint for the MiG 15. 5 years later, when American F86 Sabers face Soviet Mig 15s over Korea, they’re essentially fighting with evolved versions of the same German technology.

But remember Hans Faze jet, the one he defected with on Good Friday. That factory fresh ME262 work number one 1711 becomes the workhorse of the American test program. It flies more test missions than any other captured jet. Then on August 20th, 1946, test pilot Lieutenant Walter J. Macaulay takes it up for another routine flight near right field. At 12:40 p.m.

, one of the engines catches fire. Macaulay slows the aircraft to 150 mph, pulls the canopy release, and bails out over rural Ohio. As he jumps, the back of his head bumps the tail, knocking his helmet off. His parachute buckle cuts his chin during the opening, and he sprains his ankle landing in a cornfield.

The jet, now pilotless, noses up into a near stall, Banks left, and spirals into the ground near Lumberton, Ohio. The most historically significant ME262 to fall into Allied hands. The jet Hans Fay risked his life to deliver is completely destroyed in a cornfield two miles from where Macaulay lands. Total flight time just 13 sorties.

But the story doesn’t end there. Not even close. While American and Soviet engineers are reverse engineering the ME262, something unexpected is happening in central Europe. During the war, Germany had forced Czechoslovakian factories, particularly the massive Avia plant near Prague, to manufacture ME262 components.

When the war ends, the checks discover they’re sitting on a gold mine, complete airframes, spare engines, tools, jigs, and even buckets of original German RLM02 paint. They make a bold decision. Why reverse engineer when we can just finish building them? In August 1946, chief test pilot Antinine Krauss takes the first Czechoslovakian built Me 262, now called the Avia S92 Turbina on its maiden flight.

It’s identical to the German original. Same four 30 mm cannons. Same Jumo 0004 engines now called M04s. Same swept wings. Some are even painted with captured German paint. Over four years, Avia hand assembles 12 aircraft, nine singleseat S92 fighters and three two seat CS92 trainers. Each one takes approximately 7,000 man-hour to build.

In 1950, something remarkable happens. Czechoslovakia forms the fifth fighter flight, an alljet fighter squadron equipped entirely with S92s. These are the same jets that terrorized Allied bomber crews 5 years earlier. Now flying peacefully under a different flag. But by 1951, the era of the ME262 finally ends.

The Soviet Union starts supplying Czechoslovakia with MiG 15s, jets that are ironically influenced by the ME262, but far more advanced. The S92s are retired with most becoming training aids at aviation schools. The last operational ME262 style jet fighter flies its final mission in 1951, 6 years after Germany surrendered. Fast forward to 1993.

A group of American aviation enthusiasts launched the ME262 project with an audacious goal. Build new production ME262s using original blueprints. They borrow an original airframe M262B1, a work number one 10639 from the National Naval Aviation Museum. That’s Vera, by the way, the same trainer Watson’s whizzers used.

Using this as a template, they set out to build five aircraft. But there’s a problem with historical accuracy. Those original Junker’s Jumo 0004 engines, their death traps, built with substitute materials because Germany lacked heatresistant alloys. They lasted maybe 25 hours before burning out. The solution: General Electric CJ 610 turbo jet engines concealed inside detailed reproductions of the original Jumo 0004 B engine Nels.

To the eye, they look identical, but they’re actually 40% more efficient and vastly more reliable. On December 20th, 2002, the first replica takes flight. During the second test flight, the first attempt to cycle the landing gear in flight, disaster strikes. The gear won’t come back down. The pilot uses the emergency blowdown system.

The landing gear deploys, but on touchdown, the left main gear collapses. The aircraft is grounded for over a year for repairs. Deja vu, right? Even the replicas inherit the EM262’s temperamental landing gear, but they fix it. Five replicas are eventually completed, some two-seaters, some single seaters. Four are airworthy.

Today you can see these ME262 replicas at air shows across America and Europe. In 2023, registration DIMTT operated by Flug Museum Messmid in Germany became the first ME262 to fly in UK skies since the 1940s when it appeared at the Royal International Air Tattoo. The Collings Foundation in Houston, Texas, operates one.

Another is based in Maning, Germany. And here’s the wildest part. One restoration project is attempting to fly an original ME262 with actual rebuilt Junker’s Jumo 004 engines. The real deal, not modern replacements. The Military Aviation Museum is working to bring their ME262 replica to EAA Air Venture Oshkosh in 2025, which would be the first time this aircraft type has appeared there.

Meanwhile, only about nine original Germanbuilt Me 262s still exist in museums. The Smithsonian has one. The National Naval Aviation Museum has the original Vera that Watson’s whizzers used to train. And remember Carl Bower, Messid’s chief test pilot who taught the Americans to fly jets. The US government brought him to America in fall 1945 to support their research.

By December, he reunited with his family in Germany. In 1954, he resurfaced as an engineer for Chanceva Aircraft Corporation in Dallas, Texas, where he worked until his death in 1963. The enemy became the teacher. The teacher became American. So, what really happened to the ME262 after World War II? It became the secret blueprint for the entire jet age.

Every major power that captured one learned from it. The Americans built the F-86 Saber. The Soviets built the MiG 15. The British refined their Gloucester Meteor. The Czechoslovac just kept building them for six more years. Even Boeing’s B47 Stratjet bomber borrowed its swept wing design principles.

Look at a modern fighter jet. Any modern fighter jet. F-22 Raptor, F-35 Lightning, Euro Fighter Typhoon. Those swept wings, that’s the ME262’s DNA echoing through 80 years of aviation development. The jet was too late to save Germany. They produced about 1,430 of them, and Luftwaffa pilots claimed 542 Allied aircraft destroyed.

But by the time they entered combat in July 1944, Germany was already losing. The ME262 couldn’t change the war’s outcome, but it changed everything that came after. From Hans Fay’s dramatic defection on Good Friday 1945 to Watson’s whizzers learning to fly jets in seven minutes to Czechoslovakia secretly building them into the 1950s to modern replicas tearing through the sky at air shows today.

The ME262’s story proves that sometimes the most important battles aren’t won in combat. They’re won in the designs that come after. They’re one in the lessons learned. They’re one in the technology that gets passed down through generations of engineers who understand that the future doesn’t care who lost the war.

The messes me 262 lost World War II, but it won the future of aviation.