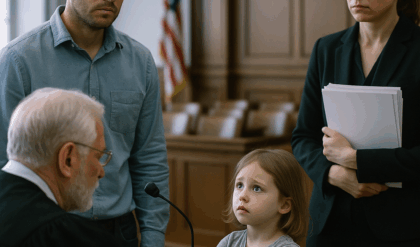

He was auctioned off while still bleeding from birth, but one rancher bought her just to give her a bed and let her sleep. Texas territory, late summer, 1879. The sun bore down on the town of Calico Ridge like the eye of something cruel. Dust rose from the trampling boots of cattlemen, drifters, and scavengers, all pressing into the square, where a makeshift wooden stage stood like an altar to everything broken.

at its center kneelled to girl, barefoot, shackled. Her name was Isa, though none present had asked. Her dress, if it could still be called that, clung to her like old smoke, torn and blood stained. Dried, rustcoled patches smeared the skirt from the knees down. Her legs trembled under her weight.

In her arms, a newborn whimpered against her chest, red-faced and too quiet. A thick iron chain looped around her right ankle, bolted to the post. Her skin was raw beneath it. “Step right up,” hollered the auctioneer, standing tall in his black vest, grin wide as a rattler’s yawn. “A two for one, folks. Young enough to mend and comes with a squealer to grow your legacy.

” Laughter broke out among the crowd. “Sheaven bleeding still,” someone snorted. “Fresh as a spring calf,” the auctioneer chuckled. Ain’t every day you get to name a babe you ain’t fathered. Aya kept her gaze on the planks beneath her knees. The crowd’s noise blurred into the thump of her heart, her lips pressed against the infant’s scalp, her only gesture of defiance, no sobs, no words. Starting at 50, the auctioneer barked.

50 for the both girl and brat. Still breath, still bleeding. Any takers? 70, someone called. 35. He slid his big hand around the table, removing only the folders. Hundreds of books, magazines, and Twitter threads. Hundreds. The price climbed like heat from the earth. With each shout, Isa’s breath grew thinner. 150. 200 from the man with a toothpick. The A voice cut through the noise.

Calm, hard as gravel. 300. Silence slammed down over the square. All heads turned. The man stood at the edge of the crowd, tall and unsmiling. A wide-brimmed hat shadowed most of his face, but the edge of his jaw was clenched like a trap set too tight. His duster coat was faded, boots scuffed.

He looked like nothing special until you saw his eyes. $300, he repeated louder this time. The auctioneer blinked. Sir, I reckon you heard wrong. It heard just fine. What’s your intent with the merchandise? Someone shouted from the crowd. The man stepped forward, boots landing like hammers on the planks. To give her a bed, to let her sleep. That’s all.

Hell of a price for charity, someone muttered. The man turned toward the heckler. Anyone want to top it? Silence. He put his hand on the revolver at his hip, not drawing it, just resting there. No. His voice dropped low, then shut up and rang the bell. The auctioneer cleared his throat and banged the gavl. Sold.

The man climbed the steps. Ayla didn’t look up until she heard the shink of his knife cutting the chain from her ankle. It dropped with a final clank. He extended a hand. She did not take it. What do you want from me? She asked. horse. The man’s voice was steady. Sleep. Then we will talk like people. She stared at him for a long second, then forced herself to her feet.

The baby muled softly. He looked at the child, then at her. Do you have a name? She hesitated. Isa. He nodded. Jack Moral. He turned toward the crowd, still staring as if trying to understand what they had just witnessed. Jack didn’t care. He placed his hand lightly on Aya’s back this way.

And with the chain still warm on the planks behind her, she stepped down from the block, barefoot, blood streaked, but not alone. The town watched them go, a girl and a stranger, walking away from a crowd that had once bought people like cattle. Not a soul followed, not a soul dared. The road to Jack Moral’s Ranch wound through low hills dusted with cedar and rock, quiet, but not empty.

Coyotes howled at twilight, and stars bled into the sky before the last ridge gave way to a spread of land hemmed by fencing and long shadows. Jack did not speak much on the ride. Ayla held the baby tight against her chest, her eyes scanning every fence post, every stretch of open space. Her feet achd from walking, her legs sore from hours of kneeling, but she never complained. The pain was familiar, expected.

Jack led her around the back of the main house. Behind the corral beside the stables, stood a weathered side cabin, one room, a small stove, a cot, and a cradle. Jack had repaired that morning with mismatched nails. “This is yours,” he said simply, opening the door. Ayla stepped inside slowly, as if expecting a trick.

The cot had clean sheets. The stove held embers still warm. A single blanket folded neatly on the edge. She did not speak. Neither did the baby. Jack set a kettle to heat on the stove, then placed a bowl of oatmeal on the table beside the cradle. I will be back in the morning, he said. You need sleep.

More than that, the child needs a mother who is not watching shadows. He started to leave. Wait. Ayah’s voice was soft, almost unused. Jack paused. She moved to the cradle, laying the baby down. Then, without turning, she said, “If you try to touch me, I will slit your throat in your sleep.” He nodded. “That is fair.” Then he stepped out, closed the door, and left her alone. The night stretched on, colder than expected. Aya did not sleep.

She fed the child from the bottle he left, swaddled him tighter, then pulled a small knife from beneath the baby’s blanket and tucked it under her cot pillow just in case. She kept listening for footsteps, for locks, for breathing not her own. But nothing came, only silence. Morning broke in a soft hush. The baby stirred.

Ayla sat up, already alert, knife still in hand. Then she saw it on the edge of the cradle. A square of white fabric worn at the corners, embroidered with fine thread, tiny bluebirds stitched into the edges. A handkerchief, not a threat, a gift. She touched it with cautious fingers.

When Jack knocked and entered, he held nothing but a bottle of warm milk and a jar of mashed apples. She watched him like he was a bear. He set the items down and nodded toward the cloth. My mother made that when I was a boy for my baby sister. She died that winter. Aya blinked. Why give it to me? Jack met her eyes. Because your child deserves more than iron chains and dirt floors. She said nothing.

He reached into his coat and placed a soft bundle of clothes, small baby things, patched but clean, beside the jar. I’ll be back by dusk. She stopped him again. Why are you doing this? Jack’s answer was quiet. Because no one ever asked you how you wanted to live.

He looked at him for a long time, the knife still tucked under her thigh. Then finally, she asked, “And what if I don’t know?” Jack gave a faint smile. Then I guess you start with sleep. He left again. This time she watched him go, and when the door clicked softly shut, Aya finally sat down on the cot, placed the baby near her heart, and closed her eyes.

Not all the way, not yet, but enough for the darkness to feel a little less cruel. The days passed like slowmoving clouds across the Texas sky. Isa did not leave the small cabin, except to fetch water or hang the baby’s cloths to dry. The ranch stayed quiet, save for the rustle of horses and the distant whistle of Jack as he worked the pens. She never asked questions.

Jack never pushed answers. But trust, like seeds dropped in rough soil, began to stir. Every morning he brought her breakfast, never more than warm bread and milk, and set it quietly on the doorstep. Sometimes he left a book with pressed flowers inside. Other times a blanket. never spoke more than needed.

The baby, who she now called Samuel in her mind, but dared not out loud, grew stronger. Aya began to sing again under her breath when she thought no one listened. Still, she never told Jack her full name. No one had ever asked it before. The town’s folk still referred to her as the girl from the auction, or worse, Chattel. That one, the market wench.

They avoided her at the trading post, stared at the scarred ring around her ankle. But Jack called her something else. Miss Isa. The first time he said it, she had been drawing water. “Morning, Miss Isa.” She’d frozen, the bucket rope burning in her palm. “What did you say?” she asked, cautious. He tilted his hat back. “Your name? I reckon you have one?” She stared, then with something like wonder, whispered, “No one has ever said it like that.” Jack shrugged, “That seems wrong.” and walked off.

Three nights later, just before dusk, thunder did not roll from the sky. It came on horseback. Four riders kicked up dust at the ranch gates. Men in canvas dusters, their faces familiar in the worst way. Ayah had seen one of them back at the square, laughing when she bled through the floorboards.

She was in the cabin when she heard the gate slam and the voic’s bark. Jack stepped out of the barn, shotgun already in hand, calm as a man who had seen worse. “Evening,” one writer said, his teeth were yellow. “We are here for what is ours.” Jack’s voice was low. “This is private land,” the man pointed toward the cabin.

“She is stolen property.” A missing asset from the flesh warrant registry took off before her paperwork cleared. She bled through her clothes, Jack replied. I paid for her outright. The man laughed. Then maybe we refund you and call it even. Jack did not laugh. He stepped forward. At this ranch, property does not breathe. That girl has lungs and a name.

One of the others leaned forward, hand near his belt. You making this legal? I am making it human. Silence held for a breath too long. Then the lead man spat on the ground. Not worth it. He yanked his res, turned his horse. The others followed. Dust and hoofprints faded into the coming dark.

Jack waited a long moment before lowering the gun. From behind the stable door, Aya stepped out slowly. You could have gotten shot, she said. Jack looked at her. So could you. Her arms tightened around the baby. What if they come back? Then we let them remember what kind of man lives here. She looked down then up again.

Miss Isa, he added gently. If you want to be called something else, I can try. She shook her head. No. She whispered. It was never the name I hated. Just the way it was said. And for the first time, she said her full name aloud. Isa Lorine. Jack nodded once. Pleasure to meet you proper, Miss Lorine.

And though the wind still carried the scent of dust and danger, something warmer settled on the porch that night, the fragile breath of someone beginning to believe she could belong. The night air had turned colder than usual. A faint wind stirred the chimes Jack had hung under the eaves, their notes soft and scattered like broken lullabibis.

Inside the cabin, Ayla curled tightly on the cot, one arm around Samuel, the other braced against her ribs as if holding herself together. Her breaths came in shallow gasps. Sleep had finally claimed her. And then the dream came. She was back in the straw, knees bent under her weight, blood soaking the earth beneath her.

Her cries mixed with the howls of animals and laughter. Cruel wheezing laughter. Boots kicked near her belly. Men shouted over her head. Not worth feeding. She’s just a hole with a pulse. Hands grabbed her legs, pulled the child out before she even finished screaming. Then cold. Endless cold.

She woke with a sob, clutching Samuel so tightly the baby whimpered. Her dress stuck to her skin with sweat. Her mouth tasted of iron and dust. She sat up quickly, breath wild. That was when she saw the light. Outside the cabin, through the small window, a single oil lamp flickered. Jack sat in an old wooden chair, coat over his shoulders, hat in his lap. The lamp burned low beside him. Ayla blinked.

Her voice cracked when she tried to speak, so she opened the door instead. He looked up as it creaked. “Bad dream?” he asked quietly. And she did not answer. He stood slow and careful, as if moving too quickly would break the air between them.

He picked up the tin mug from the small side table and walked toward her, stepped steady on the porch planks. I figured you might need this. He offered the cup. She hesitated before taking it. The scent hit her first. Lavender, chamomile, and something earthy. Not sweet, not bitter, just warm. He cradled the cup with both hands, letting the steam rise between her fingers. Jack didn’t ask what the dream was.

Didn’t try to tell her what she’d been through. He just said, “No one’s going to touch you again, Isa. Not while you’re under this roof.” She looked up slowly, eyes glassy. “How can you promise that?” “I don’t promise,” he said. “I just keep watch.” She took a sip. The tea scalded her tongue, but it helped. Jack didn’t move to go back inside.

He sat again in the chair, letting the silence fill the porch between them. I used to watch the stars with my brother, he said after a while before he joined the rangers. We would count the ones we thought were meant for us, like each one was waiting to be found. Otter said nothing, but she looked up.

The sky was cloudless, so many stars it made the dark feel crowded. She whispered, “Which one is yours?” Jack nodded toward the left. That one there next to the crooked line. Been following it since I was 13. And it hasn’t led you anywhere. It led me here, he said softly. She looked at him. Truly looked this time. His eyes were not soft, but they were steady.

The kind of steady you could lean on if you ever dared. She nodded once, then stepped back inside the cabin. Jack remained on the porch. That night, for the first time in years, Ayla slept the whole way through. No jolts, no screams, no knife in her hand, only the soft rise and fall of the child’s chest beside hers.

And outside the cabin, the lamp flickered once, then steadied, its flame burning through the dark, watched by a man who said little, but meant more. The morning sun crept slow across the fields, casting long golden lines over the fence posts and rows of corn just beginning to sprout. Aya rose before the rooster now, wrapped Samuel in a worn sling, and stepped out into the dirt with bare feet and a quiet purpose.

She no longer stayed hidden. She no longer watched the world from shadows. She moved like someone learning to belong. Her days began with goats and ended with fresh bread cooling on the sill. She knew how to mend a fence now, how to keep a fire going through the wind.

She even smiled sometimes, not at anyone in particular, but to herself, like a secret kept safe. One day, after she had milked the goats and hung fresh herbs from the porch rafters, Jack came back from town and found her hoing weeds beside the stable. You do not have to work,” he said, setting his sack down gently on the porch.

Isa looked up, sweat on her brow, dirt smudging her forearm. “I do not want to sleep forever,” she replied. Jack leaned on the post nearby, watching her for a long moment. His gaze held a softness she had not seen before. “Not pity, something else. Recognition, maybe, respect.” “My sister’s name was Laura,” he said at last. Ayla paused, the hoe still in her hands.

The breeze shifted between them, quieting the world for a moment. She was 12 when a man offered my father money to take her east. Promised schooling, a better life. Jack’s jaw tightened. I was 18. I was supposed to go after them, but I waited too long. Aya stood still, letting the words hang between them.

They sent her to one of those auction towns, Jack continued. By the time I found the place, she was already gone. No trail, no witness, just a necklace she used to wear, left in a drawer like trash. He did not cry. He just stared out toward the edge of the pasture where the wheat danced like golden ghosts in the wind.

“I have not spoken her name out loud in 5 years,” he added softly. Ella walked forward slowly, stood beside him. She said nothing, but the silence between them was not empty. It was full, full of things neither could say, and maybe did not need to. Later that week, Jack was fixing the stall hinges when the ladder shifted under him. The crash echoed across the yard.

Aya ran from the garden, Samuel still on her hip. Jack lay in the hay, jaw clenched, a gash blooming red across his forearm. You are supposed to be smart,” she snapped, dropping to her knees beside him. “Not today,” he muttered through gritted teeth. She helped him up, half dragged him to the porch, and made him sit.

“You need stitching,” she said. “I will be fine. You will be infected,” he grumbled, but she was already cleaning the wound with boiled water and a clean rag. Her hands trembled once, then steadied. She worked in silence, brow furrowed, every motion precise. She sewed carefully, biting her lip as the needle slid through his skin.

Jack did not flinch. He watched her face, the way her lashes cast shadows, the way her mouth pressed thin in concentration. “You are not afraid,” he said. “I am,” she whispered. “But not of you.” When she finished, she tied the cloth tight around his arm, sat back, and looked at her work, then at him.

His shirt clung to his chest, stre with sweat and dust. She saw the way his breathing hitched, not from pain, but from being this close. She reached out and placed her hand gently over his heart. It beat strong beneath her palm. Steady, warm, real. If I cannot trust men, she said barely louder than a breath. I still want to trust you.

Jack looked at her, his mouth parted slightly, as if afraid to speak and break the moment. Her fingers stayed there, soft against his shirt, until the baby stirred behind them. Ayla stood slowly, picked Samuel up from the porch blanket, and went back into the house without another word.

But that night, Jack found a folded note on the table beside his supper plate. Inside were just six words written in small careful script. Thank you for not giving up. He folded it once more, held it in his palm, and closed his eyes. Somewhere in that quiet, something long frozen began to thaw. The wind carried dust up from the trail, curling it around the front porch as Jack tightened the res of a new fold in the corral.

It was almost dusk. Aya was inside coughing softly, her face pale from too many days without full sleep. Then came the sound. Hooves. Four horses heavy. Jack looked up. The man who dismounted first wore a fine gray coat and a crooked smile. He was tall with rings on his fingers and the kind of voice that liked hearing itself speak. “Well, hell,” he drawled.

“Aren’t you hard to find, Miss Hila?” Jack stepped between him and the house before Isla even reached the door. She’s not yours. She is by contract. The man snapped, pulling a paper from his coat. Bought at auction. Fair and square. She was bleeding from childbirth when you chained her up. Jack said there’s no fairness in that. The man sneered.

You paid for her. Yes. Well, turns out the auction was illegal. That makes her property unpaid. You owe me $300 or the girl comes back. Ayla stood behind the screen door now, eyes wide. Jack didn’t blink. No. Then you’ll settle it like men. Jack stepped forward. High noon in the square. Bring your gun. The man smiled wide.

I was hoping you’d say that. The town had not seen a duel in three years. But at noon the next day, folks lined the main street. Dust clung to every board, every boot. Children were kept inside. Doors shut slow. Jack stood alone in the street, shirt sleeves rolled, the sun burning overhead. His hand hovered by his side.

Across from him, the man adjusted his coat, flexed his fingers over a pearl-handled pistol. The sheriff stepped out. On my count, Jack’s jaw tightened. The man licked his lips. Ha watched from the edge of the alley, holding Samuel close. The town held its breath. Three. The guns fired nearly at once. The man’s shot missed. Jacks did not.

The bullet struck clean through the man’s shoulder, spinning him down into the dust. He cried out, gun falling from his hand. Jack walked forward, slow and steady, reloading as he moved. He stood over the bleeding man and said only one thing. Men don’t buy lives and I don’t shoot to prove I can. He walked away before the sheriff even reached them. That night the fever took Isla.

She collapsed while trying to boil water. Jack caught her before she hit the ground. Her skin burned under his hands. He carried her to the bed, tucked her in tight, and sat beside her all night. When Samuel cried, Jack rocked him. When Aya moaned in her sleep, he cooled her forehead with a damp cloth.

Three nights passed like that. Jack’s eyes grew red. His hands never stopped moving. On the fourth morning, Aya opened her eyes. The first thing she saw was Jack asleep on the floor beside her cot, cradling the baby in one arm like he was made to. She tried to speak. He stirred. “Hey there,” he whispered, voice cracked from sleeplessness. “Why didn’t you send me away?” He blinked slowly ic.

She reached out weakly. He took her hand and for the first time since the auction, she smiled. Spring came late to the ridge that year. The frost clung to the windows longer than it should have, and the river behind Jack’s land took its time thawing. But when the sun finally stayed, it came strong. So did Aya. She walked again without help.

Worked the fields with her sleeves rolled, her boy tied firm to her back. Her cheeks carried color now. Her laugh, rare but real, moved like wind through the open door of the house. It was her house now, too. One morning, Aya stood by the fence with Samuel on her hip and looked out toward the far hill. “There are others,” she said.

Jack, seated on the porch with his coffee, didn’t ask what she meant. She turned to him. girls like me with nowhere to go. Still bleeding one way or another. Jack nodded slowly. What do you want to do? I want to open the back room, fix the roof, put a stove in for them. For us. By midsummer, the room was ready.

Jack and Aya cleared it themselves, nailing up new planks, repainting the walls a pale blue. They scouted town for old quilts and bartered eggs for an iron bed frame. Word spread quiet like rumors tend to do in small towns. Girls came. One had a split lip and a bundle of clothes she refused to open. Another arrived barefoot, clutching a Bible too tight to read.

They were quiet at first, then less so. Ayla taught them how to hold a child without fear. How to cook rice without burning it, how to look a man in the eyes and not flinch. She gave them beds. She gave them names. One morning, as fog still lay over the grass, Ayla found a note pinned to the barn door. No words, just a name scribbled in charcoal on the back of a tobacco slip and a bundle swaddled in torn cotton left beside it.

A baby, still pink, still crying. She dropped to her knees, lifted the child slowly like it might break, and then she did something no one had seen her do since the day she was bought. She wept, not from fear, from memory, from something deeper. Jack came running at the sound. When he saw her sitting in the dirt with the baby pressed to her chest, his breath caught. She was just left there. Ayla whispered.

She Ayla nodded. She smells like river clay. I think I think she was born yesterday. Jack knelt beside her, reached out gently to steady the baby’s head. Aya looked at him then, eyes red but steady. Where can a people leave a baby outside a barn? The kind who were never shown better, Jack said.

Isa rocked the child back and forth, back and forth. She is going to sleep inside. She said she is going to be warm. That night, under the flickering lantern light of the kitchen, Jack stood at the sink washing the last of the supper dishes. Ayla sat at the table with both babies in her arms. One born of her own blood, one born of someone else’s sorrow.

Jack dried his hands, looked over at her. For a moment, he just watched. Then he spoke. I do not have a ring, he said, voice low. I do not have much land either. But I have a name. Aya looked up. If you ever want to use it, Jack said, stepping forward. It’s yours. She blinked, then closed her eyes.

When she opened them again, they were full of tears. You do not need to give me anything, she said. I want to. She stood slowly, came to him, and placed a hand on his chest. I was sold once, she whispered. This time I choose. He touched her cheek with calloused fingers. So is that a yes. Isa nodded. I will take your name, she said.

But not just to live, to build something with you. Jack smiled, and for once it reached his eyes. Behind them, both children slept, one in a cradle, one in a basket by the fire. And in that quiet kitchen, where there had once been only silence and survival, the start of something new began. Not just safety, but home.

Two years later, the Morell homestead looked different, not larger, not grander, but fuller. The vegetable rose stretched farther now, woven between small wooden play pens and clothes lines. The barn had been painted. A second bunk house stood behind the main house, built from old pine and even older promises. A sign hung over its door. Rest here. Some who came stayed for days, some for months, a few for years, but all left with the same thing they had not arrived with, their own name.

Inside the main house, Ayla kept a journal. She wrote by lantern light after the children had gone to sleep. The house hushed, but never entirely silent, because peace did not always mean quiet. On one yellowed page, in handwriting sharper than it used to be, she wrote, “This is a place where women sleep without fear. Sometimes she stopped writing to look out the window.

She would watch Jack in the paddic, teaching their daughter how to hold the rains without fear. The little girl, Sparrow, they called her, giggled as Jack lifted her into the saddle, her small boots kicking the air. Anna would smile, then go back to writing. It was Sparrow who found the scar once. She had been running her fingers across her mother’s ankle while sitting in her lap, tracing it like a ridge on a map.

“What is that?” she asked. Aya looked down. The skin was smooth now, but the mark from the iron shackle had never faded. She hesitated, then answered plainly. That was a lock someone put on me. “Wait, because they forgot I was a person,” Sparrow frowned. “That was silly.” “Yes,” Aya whispered. “It was.

” The girl reached up and touched her mother’s cheek. “No one will lock you again.” Aya kissed her hand. “No, baby. Not ever again.” One fall afternoon, a new girl arrived, no more than 17, barefoot with a bruised lip and a threadbear dress. Isa met her at the fence. “You here to stay or to rest?” Ayah asked.

The girl looked behind her once, then whispered. “I don’t know.” Ayah smiled. “Then stay until you do.” She led her inside, gave her tea, sat with her in the warm silence of the front room. No questions, no judgment, only warmth. That night, the girl slept for 12 straight hours. Aya wrote in her journal again, “We do not save them.

We give them a place to remember who they are.” Jack never asked to be called hero. But folks started calling him that anyway. He would shrug it off, saying, “I just own some land and know how to swing a hammer.” But deep down, he knew better. He had built more than fences. He had helped build a future.

One night, he and Ayah sat beneath the stars, watching the children run between lantern poles. Jack held her hand, rough thumb tracing soft skin. “You ever think about the auction?” he asked softly. She nodded. “Not like before.” “How so? I used to hear the gabble in my sleep. Now I hear Sparrow laughing instead.” Jack turned to her. I love you.

She leaned her head against his shoulder. I know. On the last page of her journal, Ayla wrote, “I was once bought for less than a horse, but I was loved like a human, and that in the end is the only price that ever mattered.” She closed the book and set it on the shelf. Outside, Sparrow was already calling for a story.

And the homestead, glowing with the soft gold of evening light, waited for no one, but welcomed everyone. In the Old West, not every hero rode in with a badge or a bullet. Some simply gave a woman a bed and let her sleep without fear. Some love stories do not start with kisses. They start with mercy.

If this story touched your heart, do not ride off just yet. Subscribe to Wild West Love Stories for more unforgettable tales of redemption, forbidden love, and hope rising from the dust of lawless lands. Because out here, love ain’t always loud. But when it’s real, it saves.