This 1897 studio portrait of a mother and daughter looks serene until you see their eyes. The basement of the Boston Historical Society smelled of old paper and forgotten time. Laura Bennett had been working there for 3 years, cataloging donations that arrived in cardboard boxes and dusty crates, each one a small portal into the past.

On a cold February morning in 2024, she opened a box labeled simply estate sale Beacon Hill. Missing her photographs. Inside, beneath layers of tissue paper yellowed with age, Laura found dozens of photographs from the late 19th century. Most were the typical fair.

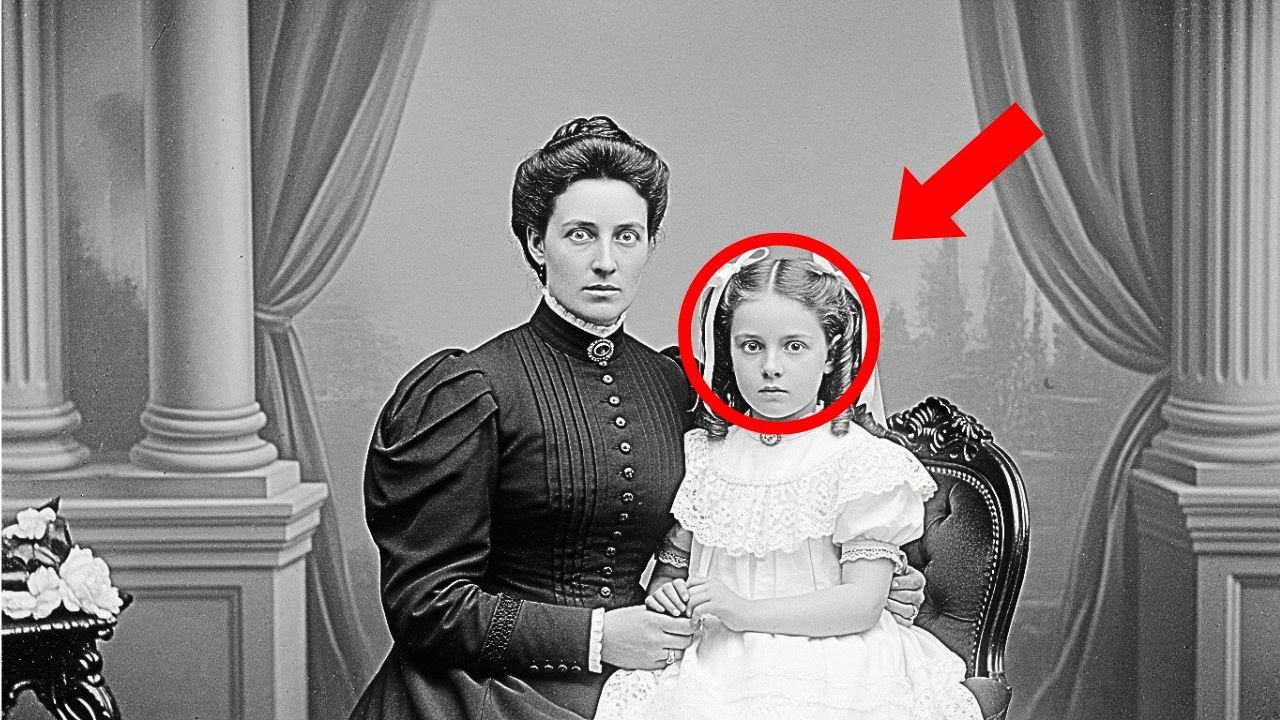

Stiffback gentlemen with impressive mustaches, children in their Sunday best, family gatherings on front porches. She had seen thousands like them, but then her hand touched a photograph that made her pause. It was a studio portrait professionally taken, the kind wealthy families commissioned in the 1890s. The photographers’s mark in the corner read Whitmore and Sun Studio, Boston, 1897. Two figures occupied the frame.

A woman in her early 30s dressed in an elaborate dark dress with a high collar and ornate buttons and a girl of perhaps seven or eight wearing a white laced dress with ribbons in her carefully curled hair. They sat in a velvet chair, the daughter on her mother’s lap, both posed in the classical Victorian style.

Everything about the photograph spoke of prosperity and respectability. The studio backdrop showed painted columns and draped curtains. The subjects wore expensive clothing. Their posture was perfect, their hands carefully positioned. It was, in every technical sense, a beautiful portrait of a refined Boston family. But something was wrong.

Laura brought the photograph closer to her face, tilting it toward the fluorescent light. The mother and daughter were smiling, or rather, their mouths were arranged into the semblance of smiles, the way photographers of that era demanded. Yet their eyes told a completely different story. The mother’s eyes were wide, almost unnaturally so, with a fixed quality that suggested not serenity, but barely controlled panic.

There was a tightness around them, a tension in the muscles of her face that contradicted the gentle curve of her lips. And the little girl, Laura felt a chill run down her spine. The little girl’s eyes held a look of pure silent terror. Her small hands gripped her mother’s arm with what seemed like desperate force, her tiny fingers white against the dark fabric.

Laura had examined thousands of Victorian photographs. She knew the conventions, the long exposure times that required subjects to hold unnaturally still, the discomfort of formal clothing, the general unease many people felt before cameras. But this was different. This was not the stiffness of Victorian formality.

This was fear captured and preserved for more than a century. She turned the photograph over. On the back, in faded pencil, someone had written, “Elizabeth and Clara, March 1897. May God forgive us.” Laura’s heart quickened. She pulled out her phone and took several highresolution photographs of the portrait, zooming in on the faces, the hands, every detail.

Then she opened her laptop and began to search the historical society’s digital archives for any mention of Elizabeth and Clara from 1897 Boston. The investigation had begun. Laura spent the rest of that day searching through the historical society’s databases, but the names Elizabeth and Clara were frustratingly common in 1890s Boston.

Without a last name, she had little to work with. She examined the photograph again under a magnifying glass, looking for any additional clues she might have missed. The studio mark Whitmore and Sons was her best lead. She searched the society’s records for information about photography studios operating in Boston during that period.

After an hour of digging through business directories and old newspaper advertisements, she found it. Whitmore’s son’s studio had operated on Tmont Street from 1889 to 1902, catering to Boston’s wealthy elite. The clothing offered more clues. And the mother’s dress with its leg of mutton sleeves and elaborate trim was expensive and fashionable for 1897.

The little girl’s white dress too spoke of wealth. White clothing was impractical and required servants to maintain. These were not middle-class Bostononians. They were from the upper echelons of society, likely residents of Beacon Hill or the Backbay. Laura leaned back in her chair, thinking if they were wealthy, there might be records.

Birth announcements, society page mentions, property records. She opened the digitized archives of the Boston Globe and began searching additions from 1897, focusing on the social columns that documented the activities of prominent families. For hours, she scrolled through microfilm scans, her eyes straining against the oldfashioned type charity events, dinner parties, arrivals, and departures, the minutiae of upper class Boston life.

Then, in the March 15th, 1897 edition, she found something that made her sit up straight. A small notice buried on page 7. Mrs. Elizabeth Ashworth and daughter Clara have departed the city for an extended rest. Mrs. Ashworth’s health has been delicate of late and the family seeks the restorative benefits of country hair. Ashworth finally a last name.

Laura’s fingers flew across the keyboard. She searched for more mentions of the Ashworth family and what she found painted a picture of Boston aristocracy. William Ashworth was listed in the 1895 city directory as a banker with a residence on Mount Vernon Street in the heart of Beacon Hill.

He served on the boards of multiple charitable organizations, was frequently mentioned in connection with the city’s financial elite. But after that brief March 1897 notice about Elizabeth and Clara’s departure, the mentions of Elizabeth vanished from the society pages. William Ashworth continued to appear at bank meetings, charitable events, gentleman’s clubs, but always alone. No wife accompanied him.

No daughter was mentioned. Laura felt the familiar tingle of a mystery deepening. She pulled out a notepad and began to list what she knew. Elizabeth and Clara had their portrait taken in March 1897, possibly just before leaving the city. The photograph showed clear signs of distress.

Elizabeth’s health was described as delicate, a Victorian euphemism that could mean anything from genuine illness to depression to something far darker. And then both mother and daughter seemed to disappear from Boston society entirely. She needed more information. She needed to find out what happened to Elizabeth and Clara Ashworth after they left the city in March 1897.

And she needed to understand why someone had written, “May God forgive us.” on the back of their photograph. Laura glanced at the clock. It was nearly 6:00 in the evening and the historical society would close soon, but she knew she wouldn’t be able to sleep without learning more.

She gathered her notes, carefully placed the photograph in an archival sleeve, and made a decision. Tomorrow, she would visit the Massachusetts State Archives. If Elizabeth and Clara Ashworth had met with tragedy, there would be records, death certificates, asylum admissions, court proceedings. The story hidden in those terrified eyes was waiting to be uncovered, and Laura was determined to find it.

The Massachusetts State Archives occupied a modern building in Dorchester. Its climate controlled rooms, a stark contrast to the dusty basement where Laura usually worked. She arrived early on Wednesday morning, armed with her notebook, the photograph, and a list of record types she needed to examine. Vital records, asylum admissions, and court documents from 1897 to 1900.

The archivist at the front desk, a middle-aged man named Robert, examined her research request with interest. The Ashworth family from Beacon Hill. He adjusted his glasses. That’s a name I haven’t heard in years. What’s your angle? Laura showed him the photograph. I’m trying to find out what happened to this woman and her daughter. They disappeared from public records in March 1897.

Robert studied the image, his expression growing somber as he noticed the fear in their eyes. Victorian Boston had ways of making inconvenient women disappear, he said quietly. Let me pull what we have. An hour later, Laura sat at a research table surrounded by document boxes. She started with death certificates, hoping she wouldn’t find what she was looking for.

She scanned through dozens of entries from March through December 1897, her finger tracing down columns of names. No Elizabeth Ashworth, no Clara Ashworth. Relief mixed with frustration. They hadn’t died, at least not in Massachusetts in 1897, but that meant they had gone somewhere else. She moved to the asylum records.

Massachusetts had several institutions in the late 19th century where wealthy families could quietly commit troublesome relatives. Mlan Hospital in Belmont, the Boston Lunatic Hospital, the Taunton State Hospital. The admission records were incomplete, many pages damaged or missing. But Laura worked through them methodically. In the MLAN hospital ledger for April 1897, she found it.

Elizabeth Ashworth, age 32, admitted April 12th, 1897. Committed by husband William Ashworth. Diagnosis: Hysteria and melancholia. Patient displays agitation and makes unfounded accusations against family members. Laura’s hands trembled as she photographed the page. Hysteria, the catch-all diagnosis Victorian doctors use to dismiss women’s illegitimate complaints, and unfounded accusations.

What had Elizabeth tried to tell people? What had she accused her husband of? She searched for any record of Elizabeth’s release or transfer, but found nothing. The Ledger simply stopped mentioning her after June 1897. No discharge date, no death recorded. Elizabeth Ashworth had entered Mlan Hospital and vanished from official records.

But what about Clara? Laura’s stomach tightened with dread as she turned to juvenile records. If William Ashworth had committed his wife to an asylum, what had he done with their seven-year-old daughter? The records for the Boston Female Asylum, an institution that housed orphaned and dependent children, provided the answer. Clara Ashworth, age 7, admitted March the 20th, 1897.

Father unable to care for child due to mother’s illness. Child is quiet and compliant, but suffers from nightmares. March 20th, just days after the photograph was taken, and weeks before Elizabeth was committed to Mlan, William Ashworth had separated them almost immediately. Laura sat back, piecing together the timeline.

Something had happened in the Ashworth household in early March 1897. Elizabeth had taken Clara to Whitmore and Sun studio to have their portrait made. A portrait that captured their terror in a way words never could. Within days, Clara had been placed in an orphanage. Within weeks, Elizabeth had been committed to an asylum for making unfounded accusations.

The photograph there hadn’t been a typical family portrait. It had been evidence. Elizabeth had known what was coming, and she had created a record of their fear. A silent testimony preserved in silver and paper. Laura needed to find out what happened next. She needed court records, property transfers, anything that would tell her how William Ashworth had managed to erase his wife and daughter from his life so completely.

And she needed to find out if Clara had survived, if she’d ever been reunited with her mother, if anyone had ever believed them. Laura spent the next two days buried in property records and legal documents at the Suffach County Registry of Deeds. The trail of William Ashworth’s financial dealings painted a picture of a man who valued control above all else.

In 1893, William had inherited his father’s banking firm, Ashworth and Company, along with the Mount Vernon Street mansion. The business had been prosperous, handling accounts for some of Boston’s wealthiest families. But Laura found something odd in the ledgers.

In early 1897, just weeks before Elizabeth and Clara’s photograph, several of the bank’s largest clients had quietly withdrawn their accounts. She cross- referenced the names with newspaper archives and found a small item in the Boston Herald from February 1897. Several prominent families have elected to transfer their banking relationships following concerns about management practices at Ashworth and Company. Mr. William Ashworth declined to comment on the matter.

What kind of concerns? Laura searched for more details but found only vague references to irregularities and questions of propriety. In Victorian Boston, such euphemistic language could mean anything from minor accounting errors to serious fraud. Then she found the court records.

In June 1897, two months after Elizabeth was committed, three former clients had filed a civil suit against William Ashworth, alleging misappropriation of funds. The case had been quietly settled out of court with all parties agreeing to seal the records. Whatever William had done, someone with power and money had helped him bury it. Laurel leaned back in her chair, the pieces beginning to fit together. William had been embezzling from his clients.

Elizabeth had discovered it. and when she had threatened to expose him when she had made what the asylum records called unfounded accusations, he had used the full weight of Victorian patriarchal law to silence her. A husband in 1897 had near absolute power over his wife. He could commit her to an asylum without proof of illness. He could control all her property. He could deny her access to her children.

And society, especially wealthy Boston society, would support him, would assume the woman was the problem, that her mind was weak, that she was hysterical. Laura felt a surge of anger for Elizabeth, trapped in an era that gave her no voice, no protection, no way to fight back except through a photograph that documented her terror.

She needed to find out what happened next. The asylum records had stopped mentioning Elizabeth in June 1897. Had she died there? Had she been transferred elsewhere? And what about Clara? Had she remained in the orphanage, or had William eventually reclaimed her? Laura returned to MLAN Hospital’s records, this time requesting access to patient death records and transfer logs.

The archivist brought her a leatherbound volume marked deceased and transferred 1897 1900. She found Elizabeth’s name on a transfer record dated July 15th, 1897. Elizabeth Ashworth transferred to Taon State Hospital. Patient remains agitated and resistant to treatment. Prognosis poor. Tauntton Laura’s heart sank. Taton State Hospital had been notorious in the late 19th century as a place where inconvenient family members were sent to disappear.

Unlike Mlan, which catered to wealthy families with some pretense of therapeutic care, Taunton was overcrowded, underfunded, and had a reputation for harsh treatment. William Ashworth had moved his wife from a relatively comfortable private institution to a state asylum where she would be forgotten, where her voice would be lost among hundreds of other institutionalized women, where no one from her former life would think to look for her. Laura made copies of every document she had found, building a case file that would have made any prosecutor

proud. But she wasn’t done. She needed to follow Elizabeth to Taton to find out if she had survived, if she had ever escaped, if she had ever seen her daughter again. And she needed to find out what had happened to Clara. The Boston Female Asylum’s records were housed at the Massachusetts Historical Society, and Laura spent Thursday morning navigating their collection. The asylum had closed in 1954.

Its records transferred to various archives, but the society had managed to preserve the admission ledgers and some correspondents. Clara’s file was thin, just a few pages that documented a 7-year-old girl’s entry into institutional life. The initial admission form dated March 20th, 1897 listed her father as her only living relative.

Her mother was described simply as indisposed due to illness, but it was the matron’s notes written in neat cursive across subsequent pages that broke Laura’s heart. March 25th, Clara remains withdrawn. She does not play with other children and speaks rarely. At night, she calls for her mother. April 10th. The child’s nightmares persist. She wakes screaming and cannot be consoled. Dr.

Morrison recommends a sedative tonic. May throwers. Clara asked again when her mother will come for her. I told her to pray and be patient. The child is bright but melancholy. Laura had to stop reading for a moment, blinking back tears. 7 years old, separated from her mother, trapped in an institution, not understanding why she had been abandoned, and Elizabeth, locked away in an asylum, powerless to reach her daughter, perhaps not even knowing where Clara had been taken.

She continued reading. The notes became less frequent as months passed. Clara fading into the institutional routine. But then in September 1897, something changed. As September 18th, received inquiry from Mrs. Sarah Cunningham regarding Clara Ashworth. Mrs. Cunningham claims to be the child’s maternal aunt and wishes to discuss Clara’s situation.

Laura’s pulse quickened. An aunt, someone from Elizabeth’s side of the family. She searched the records for more information about Sarah Cunningham and found a series of letters carefully preserved in the file. The first letter dated September 15th, 1897 was written in elegant script to the direess of the Boston Female Asylum.

I am writing to inquire about my niece, Clara Ashworth, who I understand has been placed in your institution. I have only recently learned of my sister Elizabeth’s situation and my niece’s placement. I wish to visit Clara and discuss arrangements for her care. I reside in Cambridge and am prepared to provide a suitable home. The response from the asylum was cautious. We must consult with a child’s father, Mr.

William Ashworth before allowing visits or discussing placement changes. Then came Sarah Cunningham’s reply dated September 30th. I have attempted to contact Mr. Ashworth multiple times without success. His secretary claims he is too occupied with business to address family matters. I must insist on my right to see my sister’s child.

Elizabeth would want me to ensure Clara’s well-being. I’m fast. The correspondence continued for weeks. Sarah Cunningham becoming increasingly urgent in her demands. The asylum becoming increasingly evasive. Then in late October, a tur note from William Ashworth himself dictated to his secretary, “Miss Sarah Cunningham is not to be granted access to my daughter.

She is a spinster of unstable temperament who has filled my wife’s head with unreasonable ideas. Any further interference from Miss Cunningham will be met with legal action.” After that, the letter stopped. Sarah Cunningham vanished from Clara’s file as completely as Elizabeth had vanished from public records. But Laura now had another name, another thread to follow.

She searched Boston city directories for Sarah Cunningham and found an address in Cambridge, 47 Brattle Street. The notation listed her occupation as teacher, a teacher, a woman with her own income, her own residence, independent enough to challenge William Ashworth, a woman who had tried to rescue her niece and had been threatened into silence.

Laura needed to find out what had happened to Sarah Cunningham. Had she given up after William’s threats, or had she continued to fight for Clara in other ways? And most importantly, had she known about Elizabeth’s commitment to Taon? Had she tried to help her sister as well? The investigation was expanding, revealing a web of silenced women, all connected by one powerful man who had used law and social convention to maintain his control.

Laura decided she needed help. This investigation had grown beyond a simple historical puzzle. It was becoming a story of systemic injustice that deserved proper documentation. She contacted her colleague, Dr. Marcus Green, a historian who specialized in Victorian era social institutions and gender studies.

They met at a coffee shop near Harvard Square, and Laura spread out copies of all the documents she had gathered. Marcus studied them carefully, his expression growing darker as he read through asylum records, court documents, and Sarah Cunningham’s desperate letters. “This is devastating,” he said finally. “But not uncommon. Men like William Ashworth had enormous power.

The legal system was designed to protect them, not their wives or children,” he tapped Sarah Cunningham’s letters. “This aunt, though, she was brave. Challenging a man of Ashworth’s standing could have destroyed her professionally. Schools didn’t keep teachers who caused scandals. Can you help me find out what happened to her? Laura asked. Marcus nodded. Cambridge has excellent records.

And if she was a teacher, there might be schoolboard minutes employment records. Let me make some calls. 2 days later, Marcus contacted Laura with news. He had found Sarah Cunningham’s employment records at the Cambridge Public Libraryies historical collection. She had taught at the Agassi School on Sacramento Street from 1890 to 1898.

Her employment had ended abruptly in November 1897, just weeks after William Ashworth’s threatening letter with the notation, resigned for personal reasons, but Marcus had found something more valuable. A collection of Sarah Cunningham’s personal papers donated to the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College by her grand niece in 1975. The collection included diaries, correspondents, and teaching materials.

Laura and Marcus obtained permission to examine the collection, and on a rainy Tuesday morning, they sat together in the library’s reading room, carefully opening boxes that had been sealed for decades. Sarah Cunningham’s diary entries from 1897 were a revelation. Written in tiny, precise handwriting, they documented a woman’s desperate attempt to save her sister and niece from a man she described as a tyrant who wears respectability like a mask.

August 15th, 1897. I have finally learned where Elizabeth is. Mlan Hospital then transferred to Taton. Taton, a terrible place. I wrote to her immediately, but have received no reply. I fear her letters are being intercepted. September 2nd, 1897. I went to see William. He would not admit me to the house. His secretary delivered a message.

I’m not to interfere in family matters. Family matters. As if imprisoning one’s wife in an asylum and abandoning one’s child is a private concern. September 20th, 1897. I have retained a lawyer, Mr. Peton, who specializes in family law. He says the situation is difficult.

William has complete legal authority over both Elizabeth and Clara. Unless we can prove he is unfit or that Elizabeth is being held unlawfully, the courts will not intervene. But how can we prove anything when all the power resides with him? October 10th, 1897. I visited Clara today at the asylum. They finally permitted it after Mr. Peton sent them a formal letter.

The child is thin and sad with dark circles under her eyes. She asked about her mother constantly. I wanted to take her home with me immediately, but the matron says William’s permission is required. Clara gave me something, a small drawing she had made hidden in her pocket. It shows a house with bars on the windows. She whispered, “This is where mama is.

How does the child know? Has Elizabeth found a way to send her messages? Laura felt tears welling up. Clara had known. Somehow, despite the separation, despite all of William’s efforts to isolate them, the 7-year-old child had known her mother was imprisoned. Marcus pointed to an entry from November 1897. Look at this. November 8th, 1897.

I have made a terrible decision. Mr. Peton says, “Our legal options are exhausted. The courts will not act. Society will not condemn a wealthy banker based on a woman’s accusations. But I cannot abandon Elizabeth and Clara to this fate. Tomorrow I will travel to Taon. I will see my sister and I will find a way to free her, even if it cost me everything. The diary entries ended there.

The next pages had been torn out. Laura and Marcus spent hours searching through the rest of Sarah Cunningham’s papers, looking for any indication of what had happened during her visit to Taton State Hospital. They found scattered letters, teaching notes, personal correspondence, but nothing that explained the missing diary pages or what Sarah had discovered there.

Then at the bottom of the last box, Marcus found a slim envelope marked private, not to be opened until after my death. Inside was a letter dated December 1897, written in Sarah’s handwriting, but unsigned, as if she had been too afraid to claim authorship even in her own papers. Laura read aloud, “I went to Taton on November 9th, 1897. The building was a nightmare.

Overcrowded wards, the smell of unwashed bodies, and despair, screaming echoing through corridors. I claimed to be Elizabeth’s sister and demanded to see her. The superintendent tried to refuse me, but I threatened to write to every newspaper in Boston about the conditions I was witnessing. They brought her to me in a small visiting room. I barely recognized my sister. She had lost weight, her hair was roughly cut, and she wore a stained institutional dress.

But her eyes, they were still sharp, still intelligent. She was not mad. She had never been mad. Elizabeth grabbed my hands and spoke quickly, as if she feared we would be interrupted. She told me everything. William had been stealing from his clients for years, falsifying records, creating fake investments.

She had discovered it by accident in February 1897, finding documents he had hidden in his study. When she confronted him, he threatened her. When she said she would go to the authorities, he laughed and said no one would believe a woman over her own husband. He planned it carefully. First, he sent Clara to the orphanage, using Elizabeth’s illness as justification.

Then, he had two doctors, men who owed him money, signed commitment papers, declaring Elizabeth mentally unsound. Within days, she was at Mlan. When she continued to insist on her sanity and demanded to see a lawyer, they transferred her to Taunton, where her voice would be lost among the truly ill. Elizabeth begged me to take Clara to get her daughter away from William.

She said he was not just a thief, but also cruel, that his temper was violent, that Clara had witnessed things no child should see. That was why they looked so terrified in their photograph. They had gone to the studio the day after William had learned Elizabeth was asking questions about his business. The portrait was her insurance, her evidence that something was terribly wrong. should anyone ever think to look.

Before I could respond, the attendants came and took Elizabeth away. She called back to me. Save Clara, the photograph. Make someone see. I left taunt and determined to act. But when I returned home, I found William’s lawyer waiting for me. He had papers, legal documents accusing me of defamation, threatening my employment, my reputation. If I continued to spread lies about Mr.

Ashworth, I would face prosecution. The school board had already been contacted. My position was under review. I am trapped, as surely as Elizabeth is. I have no money for a prolonged legal battle. I have no husband or father to give weight to my testimony. I’m simply a spinster school teacher making wild accusations against a respected banker.

Society will destroy me before it ever questions him. The letter ended there. Laura set it down carefully, her hands shaking with rage and grief. She gave up, Marcus said quietly. She had no choice. “But Clara,” Laura said. “What happened to Clara?” They returned to the asylum records.

Clara remained at the Boston Female asylum until 1900 when she turned 10. Then her name disappeared from the ledgers with a simple notation, discharged to father’s custody. William Ashworth had taken his daughter back after 3 years. Had he felt guilty? Had he needed to maintain appearances? Or had he simply required a child to manage his household after finally giving up any pretense of his wife’s return? Laura searched Boston city directories and census record.

In the 1900 census, William Ashworth was listed at the Mount Vernon Street address with one dependent, Clara Ashworth, age 10. No servants were mentioned, unusual for a household of that wealth. By the 1910 census, Clara was 20 years old and still living with her father. Her occupation was listed as none. She had become her father’s housekeeper, his captive in a different way than her mother had been.

We need to find out if Clara ever escaped, Laura said. If she ever learned the truth about her mother, if anyone ever believed them. Marcus pulled up marriage records on his laptop. Clara Ashworth. Clara Ashworth. Here she married in 1912. James Whitfield, a clerk. They moved to Dorchester. Laura felt a surge of hope.

Clara had gotten away from William. She had built her own life, but had she known what happened to her mother? Had anyone ever told her the truth? Laura knew she needed to finish Elizabeth’s story before she could trace Clara’s later life. She traveled to Taton, where the old state hospital buildings still stood, now converted into apartments and offices.

The modern archive was housed in a small museum dedicated to the history of mental health treatment in Massachusetts. The archivist, a young woman named Teresa, helped Laura navigate the old records. These files are heartbreaking, Teresa said as she pulled out the ledgers from 1897 took 1900.

So many women committed for reasons that had nothing to do with mental illness. Elizabeth’s file was thicker than Laura expected. It contained medical notes, treatment records, and correspondence. Laura photographed each page, her anger growing as she read the casual cruelty documented there. The notes described Elizabeth as agitated, uncooperative, and delusional.

Her delusions consisted of insisting she was not ill, demanding to see a lawyer, and claiming her husband had committed fraud. The treatments prescribed, cold baths, forced isolation, sedative drugs, were punishments disguised as medicine. But Elizabeth had been resilient. Month after month, the notes showed her maintaining her sanity despite everything.

Patient continues to be articulate and organized in her thinking, though content remains delusional. In other words, Elizabeth spoke coherently and rationally, but the doctors refused to believe her. Then Laura found a note from January 1898 that made her heart sink. Patient has grown increasingly despondent. She no longer speaks of her previous accusations.

She spends hours staring out the window. Doctor Hammond believes the reality of her situation has finally begun to break through her defensive delusions. Elizabeth had broken, not because she was mentally ill, but because the system had crushed her spirit. She had been imprisoned for nearly a year, separated from her daughter, prevented from defending herself, and drugged into submission.

The file showed she lived at Taton for 11 more years. 11 years of institutional life, of lost identity, of slow eraser. The notes became briefer over time. Elizabeth fading into just another aging female patient. Her story forgotten, her voice silenced. Laura found the death certificate dated March 3rd, 1909. Elizabeth had been 44 years old.

The cause of death was listed as pneumonia, but Laura knew the real cause. She had been killed by a system that allowed husbands to imprison their wives and by a society that refused to question male authority. Elizabeth had died without ever seeing her daughter again. She had died without anyone believing her accusations against William. She had died without justice.

But she had left that photograph, that single portrait of a terrified mother and daughter. Their eyes documenting a truth that no one had been willing to see in 1897. And now, 127 years later, someone was finally looking. Laura wiped her eyes and turned to the question that had haunted her from the beginning.

Had Clara known? Had anyone ever told her what really happened to her mother? She needed to find Clara’s descendants. If Clara had children, grandchildren, they deserve to know the truth about their grandmother and great-g grandandmother. They deserve to know that Elizabeth and Clara had been victims not of illness, but of one man’s determination to silence them. Back in Boston, Laura threw herself into tracing Clara’s later life.

The woman who had married James Whitfield in 1912 had lived in Dorchester until 1918, according to city directories. Then the trail went cold. No property records, no further directory listings, no obvious children’s birth records. Marcus suggested they search newspaper archives for any mention of Clara Whitfield or Clara Ashworth.

After hours of scanning microfilm, they found a small obituary in the Boston Globe from January 1952. Clara Whitfield, 62, died at her home in Quincy on January 14th. She is survived by her husband, James Whitfield, and daughter Margaret. Mrs. Whitfield was known for her volunteer work with the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

Private services were held. Laura read the obituary three times, her mind racing. Clara had dedicated her life to protecting children. Had that choice been influenced by her own childhood trauma? By being separated from her mother and institutionalized. The mention of a daughter, Margaret, gave Laura a new lead.

If Margaret was still alive, she would be in her 70s or 80s. There might still be time to connect her with the truth about her grandmother’s fate. Marcus searched genealogy databases while Laura contacted the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, hoping they might have records of Clara’s volunteer work.

The organization had merged with other child welfare agencies decades ago, but they referred her to the Boston Children’s Services Archive there in a box of volunteer records from the 1930s and 40s. Laura found Clara’s file. It contained letters she had written advocating for individual children, reports on home visits, and testimony she had given in court cases involving child neglect and abuse.

One letter dated 1935 stood out. Clara had written to a judge on behalf of a young girl whose father wanted to commit her to an institution. Your honor, I know from personal experience how easily a child can be separated from a loving parent and labeled as troublesome or difficult when the real problem lies with those in power.

I beg you to investigate this case thoroughly and listen to the child’s voice, not simply accept the father’s account. Children cannot defend themselves against adult authority. The law must protect them, especially when their own parents will not. Laura felt her throat tightened. Clara had never forgotten.

She had spent her adult life fighting for other children because no one had fought for her. But had Clara known the full truth about her mother? The letter suggested she understood something about unjust separations, but did she know about the embezzlement, the forced commitment, the years Elizabeth spent at Taton? Marcus found Margaret Whitfield’s marriage record. She had married David Chen in 1975.

Further searches revealed that Margaret was still alive, living in a retirement community in Newton. Laura’s hands shook as she wrote down the address. After weeks of following trails through history, she was about to connect past and present. She called the retirement community and asked to be connected to Margaret Chen, an elderly woman with a clear, strong voice, answered, “Mrs. Chen, my name is Laura Bennett.

I’m an archivist with the Boston Historical Society, and I’ve been researching your family history. I’ve discovered some information about your grandmother, Clara, and your great-grandmother, Elizabeth, that I believe you should know about.” There was a long pause, then. My grandmother never spoke about her childhood. She would become upset if we asked. We knew her mother had died when she was young, but nothing more.

What have you found? It’s a long story, Laura said. And it’s difficult, but I think you deserve to know the truth. May I visit you? Yes, Margaret said immediately. Please come tomorrow. Laura arrived at the Newton Retirement Community on a bright Saturday morning, carrying a folder with copies of all the documents she had gathered, the photograph, asylum records, Sarah Cunningham’s letters, Elizabeth’s death certificate, and Clara’s advocacy work.

Margaret Chen met her in a sunny visiting room. She was 83 years old with sharp eyes and her grandmother’s straight posture. Two other people sat with her, her son Daniel and her granddaughter Emma, both of whom had driven in from out of state when Margaret told them about Laura’s call. Laura spread the documents on the table and began with the photograph.

She watched as three generations of Clara’s descendants looked at the terrified faces of their ancestors for the first time. My god, Margaret whispered. She was so young and so afraid. Laura told them everything. She explained about William Ashworth’s embezzlement, Elizabeth’s discovery of his crimes, the systematic way he had silenced his wife and separated her from her daughter.

She showed them the asylum records, Sarah Cunningham’s desperate attempts to help, and Elizabeth’s 11 years of imprisonment at Taton. Clara was seven when this photograph was taken. Laura said she spent three years in an orphanage, knowing her mother was locked away somewhere, but powerless to reach her. When her father finally took her back, she became his housekeeper, trapped in his house until she was old enough to marry and escape.

Margaret was crying quietly. “She never told us. She never said a word. She carried it alone,” Daniel said, looking at the photograph. all that trauma and she had no one to talk to about it. Emma, who was in her 30s, spoke up, but she did do something. Look at this volunteer work. She spent her whole adult life protecting children. She made sure other kids didn’t suffer what she suffered.

Laura nodded. Your grandmother was incredibly brave, and so was your great-grandmother. Elizabeth knew she was going to be silenced, so she created evidence. This photograph, she made sure their fear was documented. She was hoping that someday someone would look at it and understand. And you did, Margaret said, reaching across the table to squeeze Laura’s hand.

127 years later, but someone finally looked. Someone finally saw. They talked for hours. Laura answered their questions, showed them every document, helped them understand the legal and social context that had allowed William Ashworth to destroy his family without consequences. She explained how common this pattern had been.

How many women had been institutionalized by husbands who wanted to silence them, how many children had been separated from mothers who loved them. Before Laura left, Emma asked a question that had been forming in her mind throughout the conversation. What happened to William Ashworth? Did he ever face justice? Laura had researched this, too. He died in 1915, a wealthy man, respected in his community.

His obituary called him a pillar of Boston society and made no mention of his wife or daughter. He was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery with a large monument. “That’s not right,” Daniel said quietly. “No,” Laura agreed. “It’s not. But we can change the narrative now. I’d like to write Elizabeth and Clara’s story with your permission.

I want to document what really happened so that history remembers them as survivors, not as forgotten victims. Margaret nodded emphatically, “Yes, please tell their story. My grandmother deserves to be remembered for her courage, and my great-grandmother deserves to be vindicated.

” Over the following months, Laura worked with the Chen family to create a comprehensive historical account. She published an article in the Journal of Women’s History documenting the Ashworth case and its context within Victorian era domestic abuse and institutional control. The Boston Historical Society mounted an exhibition featuring Elizabeth and Clara’s photograph alongside their story.

The photograph that had once documented terror and injustice became a symbol of resilience and truth. Visitors stood before it seeing not just the fear in their eyes, but also their determination to survive, to document, to leave a trace of truth for future generations to find. Margaret Chen attended the exhibition opening with her children and grandchildren. She stood for a long time in front of the portrait of her grandmother as a frightened seven-year-old child.

“We see you now,” she whispered. Both of you, we see you and we remember and we honor your courage. The photograph had waited 127 years for someone to truly look at it, to zoom in on those terrified eyes and ask the questions that should have been asked in 1897.

Laura had given Elizabeth and Clara what they had been denied in life, a voice, a witness, and justice in the form of historical truth. As visitors filed past the exhibition, reading the story of a mother and daughter who had tried to document their truth through a single photograph, Laura thought about how many other old portraits might hide similar stories. How many other women had left silent evidence of their suffering, waiting for someone to finally see.

She made a promise to herself. She would keep looking. She would keep asking questions. She would keep zooming in on the details others overlooked. Because history belonged not just to the powerful men who left behind grand monuments and flattering obituaries, but also to the silenced women and children whose fear and courage deserve to be remembered.

The photograph of Elizabeth and Clara taken in March 1897 had finally fulfilled its purpose. It had been seen. It had been believed. And the truth it contained would never be forgotten