This photo of two friends seemed innocent until historians noticed a dark secret. Dr. Natalie Chen adjusted the settings on her digital scanner as she prepared to process another batch of dgeray types from the museum’s recently acquired Montgomery collection. As the senior curator of photography at the National Museum of American History, she had handled thousands of historical images.

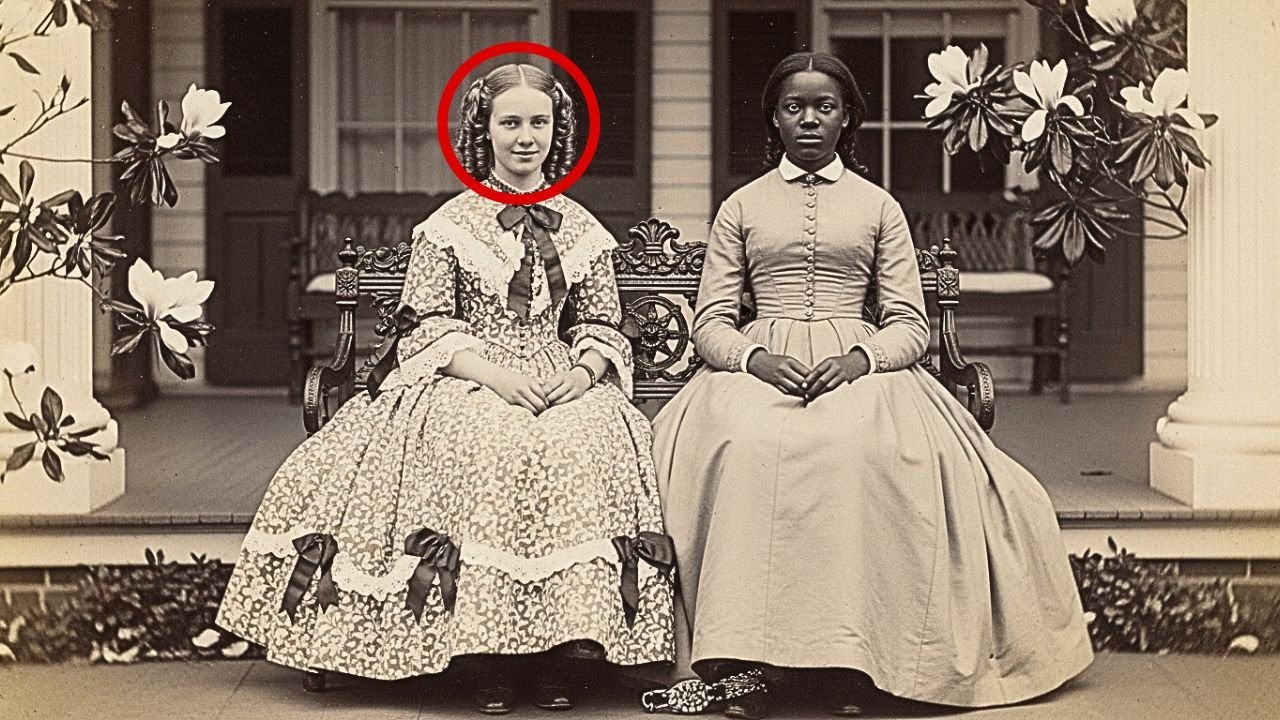

But the next photograph in the queue made her pause. The 1853 image showed two teenage girls seated side by side on an ornate bench on a plantation veranda. On the left was a white girl of about 14, her blonde hair elaborately arranged in ringlets, wearing a formal Victorian style dress with intricate lace detailing.

To her right sat a black girl of approximately 15, also wearing a fine dress, less ornate, but still remarkably elegant for an enslaved person, if that was indeed her status. What an unusual composition for that era, Natalie murmured, noting the seemingly casual proximity of the two girls. Most period photographs showing white and black individuals together depicted clear power relationships, masters and servants never equals sharing the same bench.

She carefully positioned the delicate image in the highresolution scanner. The Montgomery collection had been celebrated for its unique depictions of antibbellum southern life, and this photograph had already been featured in several publications as a rare example of exceptional interracial friendship in pre-Ivil War Louisiana.

As the enhanced digital image appeared on her monitor, Natalie zoomed in to check the quality. She methodically examined different sections of the photograph, making notes about preservation concerns. When she reached the lower portion of the image, something caught her eye. A metallic object partially visible beneath the hem of the black girl’s dress.

Wait a minute. She adjusted the contrast and sharpness, bringing the detail into focus. What initially appeared to be perhaps an anklet or decorative shoe buckle revealed itself as something far more disturbing. an ornate metal shackle disguised with decorative elements to resemble jewelry, but unmistakably a restraint attached to the girl’s ankle.

Natalie felt a chill run through her body. The supposedly heartwarming image of interracial friendship was suddenly transformed into something far more sinister, a documentation of captivity disguised as companionship. “Dr.” Whitaker needs to see this,” she said, her voice barely audible in the empty lab.

That evening, as she reviewed her notes, Natalie couldn’t shake the haunted expression she now recognized in the black girl’s eyes. What had seemed like proper Victorian stoicism now read as resigned suffering hidden in plain sight for over 170 years. The museum’s archives were housed in a temperature-cont controlled basement facility, a labyrinth of history organized in acid-free boxes and carefully labeled drawers.

Natalie spent the morning searching for any documentation related to the Montgomery plantation photograph. Here, she whispered, carefully extracting a yellowed folder containing the original acquisition notes from 1972 when the museum first received the image from the Montgomery family descendants. The accompanying letter described it as Caroline Montgomery with her companion Harriet 1853. Dr.

James Whitaker, the museum’s director of historical research, leaned over her shoulder. His interest peaked by Natalie’s discovery. Companion. That’s certainly a sanitized description. Look at this. Natalie pointed to a handwritten note attached to the original listing. The family claimed Harriet was a favored house servant who was treated almost as family.

A common self-justifying narrative, James remarked, his skepticism evident. So, have you found anything about the ankle restraint? Nothing. It’s not mentioned in any of the documentation. I don’t think previous researchers even noticed it. They continued through financial records and plantation inventories that had accompanied the Montgomery collection.

Among the sterile listings of human beings categorized as property, they found an entry from 1851. Purchased girl, age 13, $800. Intended companion for Miss Caroline. Intended companion, James repeated slowly. That’s quite specific. In a personal diary belonging to Elizabeth Montgomery, Caroline’s mother, they found a more detailed reference, acquired a suitable companion for Caroline today.

The girl is well-mannered and speaks well. Caroline is delighted with her new friend. Though we’ve taken precautions to ensure she remains reliable, Thomas has crafted a special arrangement that is both secure and befitting her position. Natalie felt her stomach turn at the casual cruelty of the passage.

The special arrangement, they’re describing the decorative shackle as if it were a privilege. Further entries revealed more about this arrangement. Caroline and Harriet spent the afternoon reading together. Harriet’s education is proving useful, though we must be careful not to let her forget her place. The gold filigree was a good choice, elegant enough for her to be seen with Caroline in public.

“This is worse than I thought,” Natalie said quietly. “She wasn’t just enslaved. She was forced to perform friendship while being literally chained. A pet slave for a lonely plantation daughter,” James nodded grimly. “We need to look for other examples. If this was happening on the Montgomery plantation, it was likely occurring elsewhere.

” The National Archives in Washington DC housed thousands of narratives from formerly enslaved people collected during the Federal Writers Project of the 1930s. Natalie had arranged for research access, hoping to find any mention of Harriet or similar companion arrangements on other plantations. After days of methodical searching through digitized records, she found something remarkable.

An interview with an elderly woman named Harriet Johnson recorded in 1937 in Chicago. The birth year in Louisiana origins matched the girl in the photograph. Listen to this,” Natalie said to James, who had joined her research expedition. “I was purchased special to be a friend to the daughter, Miss Caroline. They dressed me fine, taught me to read some, though it was against the law.

But don’t let that fool you about kindness. I wore gold chain on my ankle for 4 years, only removed when I was safely locked in my room at night.” James leaned forward, excitement building. That has to be her. The narrative continued. They called it my special bracelet. Said it was a privilege to wear gold when other slaves wore iron.

But a chain is a chain, no matter how pretty. Miss Caroline, she liked to pretend we were true friends. Maybe she even believed it. But friends don’t own friends. Harriet described how she was required to speak properly, dress elegantly, and accompany Caroline everywhere, from meals to social events to lessons. She was displayed as evidence of the Montgomery family’s enlightened treatment of their enslaved people.

While the decorative shackle ensured she couldn’t escape, “The photographer came for Miss Caroline’s 14th birthday.” The narrative continued. They dressed me in one of my finest dresses, still plain next to hers, and posed us together. Miss Caroline was so proud of that picture, said it showed how special our friendship was. Never saw that the chain on my ankle told the true story.

The account detailed Harriet’s eventual escape during the chaos of the Civil War. She fled north where she married, raised children, and ultimately shared her story with the Federal Writers Project interviewer decades later. “She survived to tell her story,” Natalie said softly, feeling a connection across time to the girl in the photograph.

And now we can make sure it’s heard. The final passage of Harriet’s narrative struck Natalie powerfully. People today might look at the picture and see two girls being friends, not knowing one was property to the other. That’s how slavery worked. Sometimes it dressed itself up pretty, but underneath was always chains. The discovery of Harriet’s narrative energized Natalie’s research.

If one companion arrangement had been documented, others likely existed. She assembled a small research team, including Dr. Marcus Johnson, an expert on enslavement practices, and Emily Parker, a digital imaging specialist. “Do we need to reexamine every supposedly friendly photograph of enslaved and free people together,” Natalie explained during their first strategy meeting, looking specifically at the lower portions of images, which might have been cropped in published versions.

“They developed an algorithm to scan the museum’s digital archives for similar visual patterns, formal portraits showing black and white individuals in close proximity, particularly children and young women. We’ve identified 43 potential matches, Emily reported two weeks later, bringing a tablet with a carefully organized collection of images.

In seven of them, we can clearly identify disguised restraints, decorative shackles, chains masked as jewelry, even what appears to be a gold ribbon tied around an ankle that’s actually a thin metal band. Marcus nodded grimly as he examined the evidence. This fits with my research on what plantation owners called companionate enslavement.

A particularly insidious practice where enslaved children were forced to serve not just as servants, but as emotional companions to white children. The psychological cruelty is staggering, Natalie observed, forcing someone to perform friendship while keeping them in bondage. Their findings extended beyond photography. Marcus uncovered plantation records from Georgia, Virginia, and the Carolinas that included specific references to companion acquisitions and appropriate restraint practices for house companions. A diary from a Virginia

plantation mistress was particularly revealing. Purchased a bright young girl for Mary’s companion. Had the silver smith craft an attractive chain that won’t embarrass us when they appear together in society. The Black Moores were quite impressed with our arrangement and are seeking a companion for their own daughter.

It was a status symbol, Marcus explained. Having an elegantly dressed, well spoken, enslaved companion for your daughter demonstrated both wealth and supposed benevolence, all while maintaining absolute control. The team discovered that these arrangements were particularly common for plantation daughters who were isolated on rural estates with few social opportunities with other white children their age.

The enslaved companions filled this void, but always with the underlying reality of ownership maintained through visible yet disguised restraints. These weren’t exceptions or anomalies, Natalie concluded as they compiled their research. This was a recognized practice hiding in plain sight in our historical records and photographs.

The conference room fell silent as Natalie finished presenting her team’s findings to the museum’s exhibition committee. The projected image of Harriet and Caroline remained on the screen, the enhanced section clearly showing the disguised shackle. This completely changes how we should display and interpret this photograph, Natalie concluded.

And potentially dozens of others in our collection. Richard Townsend, the museum’s senior director, looked troubled. This is powerful research, Dr. Chen, but we need to consider the implications carefully. The Montgomery collection was donated with considerable funding for its preservation and exhibition. The Montgomery family descendants sit on our board.

All the more reason to be truthful about what these images actually show. Natalie countered, “This isn’t just about one photograph. It’s about correcting a fundamental misrepresentation of history.” Dr. Eliza Washington, head of African-American history collections, leaned forward. I agree with Natalie. We have a responsibility to present these images accurately, especially given that we now have Harriet’s own testimony.

Anything less would perpetuate the eraser of her experience. The debate continued for hours. Some committee members expressed concerns about donor relationships and potential controversy. Others worried about reinterpreting long-established collection narratives. The marketing team fredded about public relations challenges.

“What would you propose specifically?” Richard finally asked Natalie. “A special exhibition called Hidden in Plain Sight,” she responded without hesitation. centered on the Montgomery photograph, but including the others we’ve identified. We present the original interpretations alongside what we now understand, the disguised restraints, the forced companionship, and most importantly, Harriet’s own words describing her experience.

Eliza nodded approvingly. We could include interactive elements where visitors discover the hidden details themselves, just as Natalie did. It would be powerful experiential learning about how history can be obscured. And we include modern parallels, added Marcus, how exploitation can hide behind benevolent facads.

Now we need to look more carefully at historical narratives that seem too comfortable. Richard sighed, visibly weighing institutional politics against scholarly integrity. The Montgomery family representatives will need to be informed before we proceed. Of course, Natalie agreed. But they should be presented with our findings as historical fact, not as a point of negotiation. The evidence is clear.

And it’s this. As the meeting adjourned, Natalie lingered, looking at the projected image of Harriet. We owe her this truth, she said quietly, though no one remained to hear her. The elegant conference room at the law offices of Hartwell and Reed featured mahogany paneling and portraits of stern-faced men in expensive suits.

Natalie sat beside Director Townsend, facing three representatives of the Montgomery family and their attorney. “This is preposterous,” declared Eleanor Montgomery Williams, a silver-haired woman in her 70s. “You’re defaming my ancestors based on a shadow in an old photograph.” Natalie calmly opened her tablet and displayed the enhanced image.

“It’s not a shadow, Ms. Montgomery Williams. It’s clearly a decorative restraint, and we have Harriet’s own testimony describing it. Oh, some interview with an old woman who claimed to be this Harriet person. How can you possibly verify that? The details match precisely. The dates, names, location, even the specific description of the gold filigree restraint, Natalie explained.

Additionally, we found your great great grandmother’s diary entries describing the arrangement. Ellanar blanched slightly at this revelation. Richard attempted diplomacy. We understand this is difficult information to process. The museum isn’t attempting to single out your family. We’ve discovered similar practices were relatively common.

My ancestors were respected members of Louisiana society, Elellanar insisted. They treated their people well for the times. With respect, Marcus interjected, having joined the meeting as their historical expert. Forcing a young girl to pretend friendship while keeping her shackled isn’t treating someone well by any era’s standards.

The Montgomery family’s attorney cleared his throat. The donation agreement gives the family certain rights regarding how these materials are displayed. We could pursue an injunction. You could, Richard acknowledged, but that would merely delay the inevitable. Dr. Chen’s research is academically sound and will be published regardless.

The question is whether your family wishes to be part of an honest historical reckoning or prefers to be seen as attempting to suppress the truth. But a younger Montgomery relative who had been quiet until now spoke up. Grandmother, perhaps we should consider a different approach. Times have changed since the collection was first donated.

After tense negotiations, a compromise emerged. The Montgomery family wouldn’t block the exhibition, but would be allowed to include a statement acknowledging that while their ancestors participated in a morally unacceptable system, they were also products of their time and place. As they left the meeting, Ellaner stopped Natalie.

You think you’re doing something noble, but you’re just stirring up painful history better left buried. Natalie met her gaze steadily. Harriet couldn’t tell her story while she was chained, but she lived to make sure it was recorded. Don’t you think she deserves to be heard now? With the Montgomery family negotiations behind them, Natalie’s team focused on expanding their research.

The museum had approved the exhibition, scheduled to open in 6 months. Now they needed to build a comprehensive understanding of the companion slave practice. “Look at this,” Emily called from her workstation. She had been analyzing a collection of letters between plantation family. “There’s an entire correspondence between the Montgomery’s and the Whitfield family in Georgia about the companionship arrangement.

They were essentially sharing tips when the letters revealed a network of elite families who had adopted similar practices. Elizabeth Montgomery had apparently pioneered the decorative restraint concept which was subsequently copied by other plantation mistresses who saw it as a refined solution to their companion management.

Marcus had been tracking financial records. I found specialized purchases from jewelers and silvermiths entries specifically for decorative anklets and companion bracelets. Some even include design specifications to ensure they couldn’t be removed without a key. The team discovered that these arrangements were most common among wealthy families with daughters between 10 and 16 years old.

The enslaved companions were typically slightly older than the white children they served, selected for intelligence and appearance, and often given unusual privileges like fine clothing and basic literacy, always with the underlying control maintained through physical restraints and psychological manipulation.

It’s a particularly gendered form of enslavement, observed Dr. Washington as she reviewed their findings. These girls were expected to provide not just service but emotional labor to appear genuinely attached to their enslavers. In auction records, they found evidence that enslaved children advertised as suitable companions commanded higher prices.

Some listings specifically mentioned well-mannered, refined features or pleasing temperament. Euphemisms for children who could convincingly perform the role of friend. Most disturbingly, they found photographs of plantation daughters with their companions featured in family albums presented as evidence of the family’s supposedly benevolent treatment of their enslaved people.

In many cases, the restraints were carefully positioned to remain just out of frame or disguised as decorative elements. They weren’t hiding these arrangements, Natalie realized. They were proud of them. They saw them as enlightened, the ultimate display of power, Marcus added. Not just owning someone’s body, but claiming ownership of their emotions and relationships, too.

forcing them to simulate friendship while ensuring they could never forget they were property. This understanding added layers of complexity to their exhibition planning. It wasn’t just about exposing hidden restraints and photographs, but about revealing an entire system of emotional exploitation that had been obscured by sanitized historical narratives.

The research team expanded their search beyond the museum’s own collections, reaching out to other institutions and private archives across the country. Their inquiries generated both interest and resistance as curators and collectors grappled with the implications for their own historical photographs. The Historical Society of Louisiana has identified three more images with similar characteristics, reported Emily during their weekly progress meeting.

And they found an estate inventory that specifically lists companion restraints among the valuables. As word of their project spread through academic circles, Natalie began receiving emails from researchers who had noticed similar anomalies, but hadn’t understood their significance. A pattern was emerging across the South, concentrated among the wealthiest plantation families. Dr.

Washington had been conducting oral history research, reviewing interviews with formerly enslaved people for mentions of companion arrangements. I found 11 accounts that describe similar situations, though not all mentioned the decorative restraints specifically. Some talk about being locked in at night or about wearing specific tokens that mark them as belonging to the daughter of the house.

The most powerful breakthrough came when they located a descendant of another companion, a woman named Gloria Thompson, whose great great-grandmother, Rachel, had been forced into a similar arrangement with the daughter of a Virginia tobacco planter. “My grandmother passed down Rachel’s story,” Gloria explained during their recorded interview how she had to dress up and play with little Miss Charlotte every day, but wasn’t allowed to speak to the other enslaved children because she might pick up their common ways.

She slept on a pallet in Miss Charlotte’s room, chained to the bed frame every night. Gloria had preserved a small object, a decorative gold cuff with an internal locking mechanism passed down through generations. Rachel kept this after she escaped during the war. Said she never wanted her children to forget what pretty things could hide.

The cuff was nearly identical to the one visible in the Montgomery photograph, confirming that these were manufactured items, not one-off creations. As their research database grew, they identified over 60 clear examples of the practice spanning from the 1830s to the Civil War, concentrated among elite families in Virginia, Georgia, and Louisiana.

The physical evidence combined with written and oral testimonies painted a comprehensive picture of a widespread yet previously unrecognized aspect of slavery’s psychological control. Each of these photographs tells the same story, Natalie observed as she reviewed their collection. A story of friendship that wasn’t friendship at all, of chains disguised as jewelry, of childhood stolen and replaced with forced performance.

The exhibition was taking shape not just as a revelation about hidden restraints in old photographs, but as a powerful exploration of how history conceals its darkest aspects behind seemingly innocent images. The National Museum of American History buzzed with anticipation on opening night of Hidden in Plain Sight: Captive Companions.

Media representatives, academics, and members of the public filled the speciallyesed gallery space where the exhibition was housed. The centerpiece was an enlarged version of the Montgomery Plantation photograph with interactive lighting that illuminated the disguised shackle when visitors pressed a button. Around it, similar photographs were displayed with their hidden restraints revealed through careful enhancement and thoughtful presentation.

Beside each image were the stories of the enslaved girls drawn from historical records, diaries, and where possible, their own testimonies. Harriet’s narrative featured prominently, her words displayed in elegant typography alongside the photograph where she had been forced to pose as Caroline’s friend. “We’re not just showing what was hidden in these photographs,” Natalie explained to a reporter from the Washington Post.

“We’re revealing how history itself can hide disturbing truths behind seemingly innocent images. These girls were required to perform friendship while being physically restrained and emotionally manipulated.” The exhibition included Gloria Thompson’s family heirloom, the golden restraint cuff displayed in a central case.

Visitors could examine its ornate exterior, and the hidden locking mechanism that transformed jewelry into a tool of captivity, a digital interactive station allowed people to examine unaltered historical photographs and discover the hidden restraints for themselves, creating moments of revelation similar to Natalie’s original discovery.

The exhibition also featured contemporary commentary on how historical narratives are constructed, challenged, and revised as new evidence emerges. Reactions were powerful and varied. Some visitors wept as they read the personal testimonies. Others engaged in intense discussions about historical memory and responsibility.

A few descendants of plantation families expressed discomfort or defensiveness, while descendants of enslaved people thanked the museum for finally telling this hidden story. Elellaner Montgomery Williams attended with several younger family members, though she maintained a stoic expression throughout.

Natalie noticed one of the younger Montgomery’s openly crying in front of Harriet’s testimony. Most powerfully, descendants of identified companions had been invited as honored guests. Gloria Thompson stood proudly beside the case containing her ancestors restraint, explaining its significance to visitors. Rachel wanted us to remember, she told them, not to hold on to bitterness, but to recognize truth when others tried to disguise it.

As the evening concluded, Director Townsend approached Natalie. The board chairman called it the most significant historical reframing the museum has undertaken in decades. He smiled slightly. Worth all the controversy, wouldn’t you say? Natalie watched as a young black girl studied Harriet’s photograph intently.

absolutely worth it. One year after the exhibition opened, Natalie sat in her office reviewing its impact, hidden in plain sight, had traveled to seven major museums across the country, sparking similar research projects and re-evaluations of historical photography collections nationwide. The academic paper she had co-authored with Marcus and Dr.

Washington had been published in the American Historical Review, generating both a claim and productive debate. Over 40 additional companion photographs had been identified by other researchers using their methodology, creating a comprehensive understanding of what had once been an invisible practice. Most significantly, the project had inspired a broader movement to re-examine seemingly benign historical narratives and images for hidden evidence of oppression and resistance.

Museums and universities were developing new protocols for analyzing historical photographs, looking beyond the obvious to find the stories concealed in details and margins. A knock at her door interrupted her thoughts. A young intern entered carrying a small package. This was delivered for you, Dr. Chen, from someone named Eliza Montgomery.

Natalie recognized the name, one of Ellanar’s granddaughters, who had been visibly moved at the exhibition opening. Inside the package was a leatherbound volume and a note. Dr. Chen, found this in Grandmother Eleanor’s effects after her passing last month. It’s Caroline Montgomery’s personal diary from 1853 or 1855.

I believe it belongs in your research collection, not hidden in our family attic. Eliza, with careful hands, Natalie opened the fragile diary. Caroline’s girish handwriting filled the pages, documenting her days with Harriet. The entries revealed a complex relationship, moments of genuine affection alongside disturbing expressions of ownership and control.

Caroline had been both companion and captor. Her perspective shaped by the society that taught her to see ownership of another human as natural. One entry stood out. Harriet looked sad today. I told her she’s lucky to be my friend instead of working in the fields like the others.

She said nothing, but I saw her touching her ankle chain when she thought I wasn’t looking. Sometimes I wish she didn’t have to wear it, but mother says it’s necessary. I gave her a ribbon to tie around it to make it prettier. Natalie closed the diary, feeling the weight of its significance. The final piece of the story, Caroline’s perspective, added yet another dimension to their understanding.

Not a simple tale of villains and victims, but a complex human tragedy in which even the privileged were shaped by a fundamentally cruel system. She would add the diary to their growing archive of companion documentation, ensuring that both Harriets and Caroline’s perspectives were preserved. This was the true power of their work, not just exposing hidden chains, but revealing the full humanity of all involved, trapped in different ways by history’s terrible bindings.

As she placed the diary carefully in an archival box, Natalie thought about the photograph that had started everything. A seemingly innocent image that once truly seen could never be viewed the same way again, just like history itself.