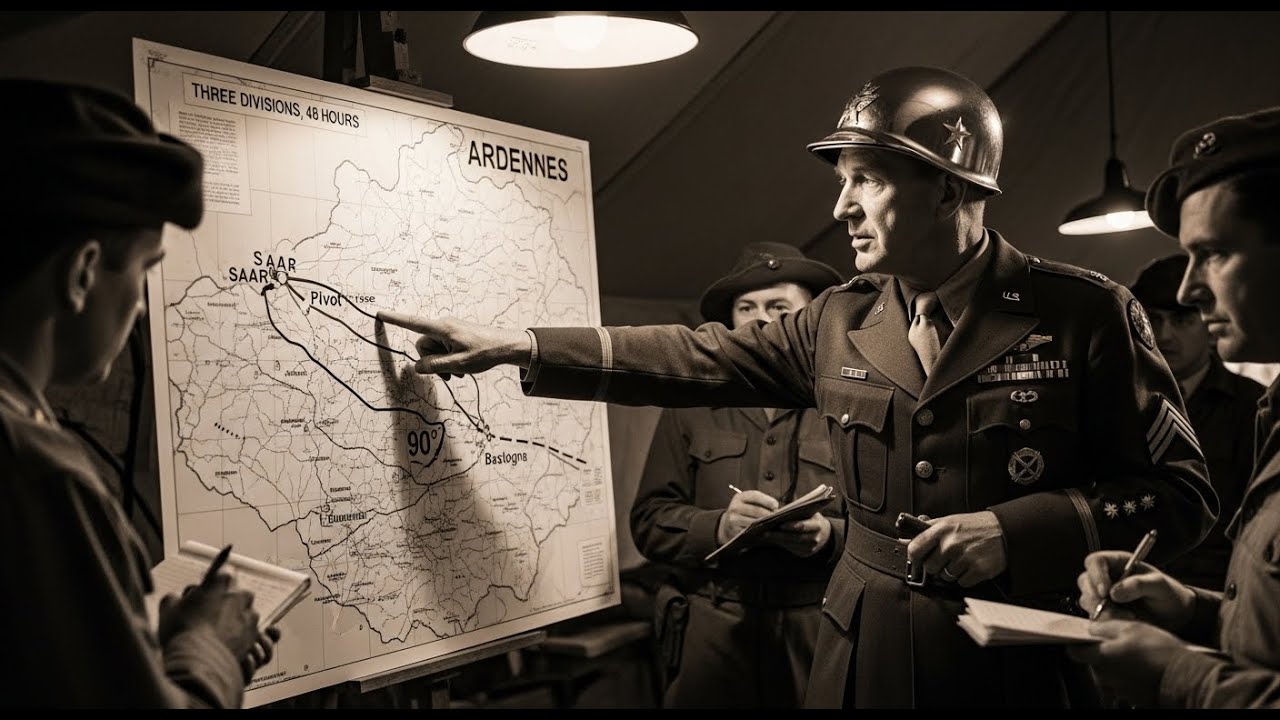

Impossible. Unmoglish. That was the word echoing through German high command. On December 19th, 1944, American General George S. Patton had just announced he would disengage three full divisions from active combat, rotate them 90° north, march them through the worst winter in decades, and attack the southern flank of Germany’s Arden offensive in 48 hours.

German generals laughed. Their intelligence officers called it American propaganda. Field Marshal von Runstead declared no army could execute such a maneuver in less than a week. They were all wrong. And their reactions captured in intercepted communications, diary entries, and post-war interrogations reveal just how completely Patton’s impossible achievement shattered German confidence and turned the Battle of the Bulge from potential German victory into catastrophic defeat.

Today, we’re revealing what German commanders actually said when Patton did the impossible. When German intelligence first intercepted American communications about Patton’s Third Army pivoting north, the reaction wasn’t fear, it was mockery. In the command bunker of German Army Group B, Field Marshal Walter Mod reviewed the intelligence report and dismissed it as Allied disinformation.

“Patton is fighting in the SAR,” he told his staff. This is a deception to make us believe he can be in two places at once. German operational planning for the Arden’s offensive cenamed Vakt Mrin relied on one critical assumption. It would take the allies at least a week to shift forces from other sectors to respond to the breakthrough.

German commanders had studied Allied doctrine, logistics capabilities and command structures. They knew moving large formations required extensive planning, supply coordination, and time. A 90deree pivot of three divisions through winter conditions, two weeks minimum, possibly three. Colonel General Alfred Jodel, chief of operation staff at German high command, was more analytical in his assessment.

His diary entry from December 19th, noted, “American radio intercepts suggest Patton’s third army will attack our southern flank within 48 hours. This is either brilliant psychological warfare to discourage our advance or American commanders have completely lost touch with operational reality. No army in history has executed such a maneuver in such conditions in such time.

Even General Obururst Heins Gderrion, the father of German panzer tactics and an expert in mobile warfare, couldn’t believe it. When informed of Patton’s announcement, he reportedly said, “If Patton actually accomplishes this, I will have to rewrite everything I know about armored operations.” Gderion understood armor and logistics better than almost anyone alive.

He knew the fuel requirements, the coordination needed, the planning involved. What Patton was promising violated every principle of operational art. German field commanders on the southern flank of the bulge received orders to prepare for possible American counterattacks, but not for three or four days. Forward units were told to focus on advancing west, not defending south.

The German 7th Army, responsible for the southern shoulder, was allocated minimal reserves because high command didn’t believe a major threat could materialize that quickly. This disbelief was Germany’s first critical mistake. By the time they realized Patton wasn’t bluffing, it was too late to shift their operational focus.

December 21st, 1944, German confidence began cracking. Reconnaissance units reported massive American troop movements heading north from the SAR region. Not small units, entire divisions with full equipment trains. Radio intercepts confirmed Third Army units were disengaging from combat and repositioning. Most alarming Luftwafa aerial reconnaissance despite terrible weather spotted long columns of American vehicles moving through the snowstorm at Army Group B headquarters.

Field Marshall Model’s tone changed dramatically. His chief of staff, General Hans Krebs, recorded the conversation. Model paced the command room repeatedly asking how this was possible. He demanded our intelligence officers explain how Patton was accomplishing in 2 days what should take 2 weeks.

German logisticians ran the calculations and concluded the Americans were doing something impossible to move three full divisions with their support elements. Approximately 133,000 men, 11,000 vehicles, tanks, artillery, ammunition, fuel, and supplies through winter conditions on roads shared with other Allied units required coordination that shouldn’t be achievable.

One German quartermaster officer wrote in his report, “Either the Americans have developed supernatural powers or our understanding of logistics is fundamentally flawed. The psychological impact on German commanders was significant. They had based the entire Arden’s strategy on Allied predictability and slowness to respond.

Suddenly that fundamental assumption was collapsing. If Patton could do this, what else were the Americans capable of?” General Dar Panser trooper Hasso Fon Mantoyful commanding the fifth Panser army was one of the first to grasp the implications. He sent an urgent message to model. If third army attacks our southern flank in force while we are extended westward, our spearheads will be isolated.

We must either accelerate the advance to the muse immediately or prepare defensive positions to the south. But accelerating was impossible. German spearheads were already struggling against American resistance at St. Vith and Bastonia. Fuel shortages were critical. The Germans had planned to capture American fuel dumps, but stubborn American resistance had prevented this.

German armor was literally running dry. The irony wasn’t lost on German officers. Here was Patton supposedly moving three divisions through a blizzard while German Panzer units were immobilized for lack of fuel. Colonel Hans Vanluck, commanding a Panzer Regiment, later wrote, “We began to realize we were fighting an enemy with capabilities we had underestimated.

The Americans we thought of as amateurs were outmaneuvering us with an operational flexibility we could no longer match. By December 22nd, concern had turned to alarm. Patton’s forces weren’t just moving. They were actually forming up for attack. This wasn’t propaganda or deception. It was real. And German high command had no prepared response.

December 22nd, 1944. 6:00 a.m. Patton’s fourth armored division smashed into German positions on the southern flank of the bulge. The shock was total and immediate. German units that had been told they had several days to prepare were hit by a full-scale American armored assault barely 72 hours after Patton had announced his intention.

The German 7th Army command post erupted in chaos. General Depancer tropa Eric Brandenburgger commanding the southern shoulder sent a frantic message to army group B under heavy attack from American armor. Multiple divisions this is not a probe. This is a major offensive. Patton has actually done it.

Field marshall models response recorded in command logs revealed his stunned disbelief. Confirm that this is third army. Confirm Patton himself is directing the attack. How is this possible? When confirmation came that it was indeed Patton’s forces in full strength, Model reportedly threw down his marshall’s baton and declared, “We are fighting a genius.

” German soldiers on the receiving end of Patton’s attack were equally shocked. Lieutenant Hans Schmidt, whose unit faced the fourth armored division, recorded in his diary, “The Americans appeared out of the snowstorm like ghosts. We were told they couldn’t possibly arrive for days. Yet here they were in overwhelming strength, attacking with a coordination and ferocity we hadn’t seen before.

They fought like men possessed. At German high command in Berlin, the atmosphere turned grim. Hitler had personally guaranteed that the Americans couldn’t respond effectively to the Arden’s offensive. He had predicted at least 10 days before any coordinated counterattack. Patton had destroyed that prediction in under 3 days.

When informed of the attack, Hitler’s response was characteristic. He blamed his intelligence officers for incompetence and his field commanders for weakness. He refused to accept that an American general had simply outthought and outexecuted German operational planning. But the professional German officers knew better.

General Al infantry Gunther Blumenrit chief of staff to field marshal funded wrote in his afteraction report. Patton’s relief of Bastonia represents one of the most brilliant operational achievements of the war. To disengage from combat, move three divisions through winter conditions and launch a coordinated attack within 48 hours requires staff work, logistics coordination, and command excellence that exceeded anything we accomplished.

Even in our victories of 1940, the German southern flank began collapsing. Units that should have been advancing west were instead fighting desperately to hold positions against third army’s assault. The careful German timetable, already behind schedule, was now completely disrupted. Patton’s attack didn’t just relieve Bastonia, it broke the operational logic of the entire Arden’s offensive.

As Third Army’s Fourth Armored Division broke through to Bastonia on December 26th, German high command faced a brutal realization. The Arden offensive had failed. Not because of American resistance at individual strong points, though that was heroic. Not because of fuel shortages, though those were critical.

The offensive failed because George S. Patton had done something German planning assumed was impossible. Field marshal Geron Runstead, overall commander of German forces in the west, held a command conference on December 27th. The minutes of that meeting captured after the war, revealed the depth of German consternation.

Fon Runstead opened with a damning assessment. We built our entire strategy on the assumption that Allied response would be slow, disorganized, and reactive. Patton has proven that assumption catastrophically wrong. We are no longer fighting the hesitant, cautious allies of 1942 and 1943. We are fighting an enemy who has learned to operate with a speed and decisiveness that matches or exceeds our own capabilities.

The strategic implications cascaded through German planning. If the Americans could move three divisions 90° in 48 hours, then German operational security was meaningless. Any concentration of German forces could be met with rapid American response. The entire concept of surprise offensive operations, the core of German tactical doctrine, was obsolete against an enemy with such operational flexibility.

German panzer commanders were particularly shaken. General Dare Panser troopa Hinrich Fryhair Fon Lutvitz whose forces had been diverted from the drive to the muse to counter Patton’s attack wrote bitterly, “We created the concept of mobile armored warfare. We wrote the doctrine of rapid maneuver and breakthrough exploitation. Now an American general is using our own concepts against us and doing it better than we can. This is a bitter pill.

At Hitler’s headquarters, the Furer’s response was predictable but revealing. He insisted the offensive continue, that more resources be committed, that determination would overcome operational reality. But his generals knew better. Model Mantol and von Runstead all privately acknowledged that continuing the offensive was pointless.

Patton’s relief of Bastonia had demonstrated that American forces could respond faster than German forces could exploit breakthroughs. The psychological impact extended beyond individual commanders. German soldiers began to question whether victory was still possible. They had been told the Americans were poorly led, poorly trained, and lacked German military excellence.

Patton’s achievement shattered that propaganda. German troops who had fought confidently in 1940 and 1941 now faced an enemy who could outthink, outmaneuver, and outfight them. The Battle of the Bulge continued for weeks. But German commanders knew from December 26 onward that they had lost. Patton’s 48-hour miracle hadn’t just relieved one surrounded unit.

It had broken the back of Germany’s last major offensive and proven that American military capability had surpassed German expertise. After Germany’s surrender, Allied intelligence officers interrogated captured German commanders extensively. The conversations about Patton’s relief of Bastonia were particularly revealing. These weren’t men trying to excuse defeat.

They were professional soldiers trying to understand how they had been so completely outmaneuvered. Field Marshal Wilhelm Kaidle, Chief of the Armed Forces High Command, was interrogated in May 1945. When asked about Patton, Kaidle responded, “We made the mistake of believing our own propaganda about American military incompetence.

Patton destroyed that illusion. His ability to move an entire army through a blizzard and attack within 48 hours demonstrated operational excellence that we could not match in 1944. Perhaps we could have done it in 1940 when our army was at its peak. By 1944, we had lost that capability. Patton still had it. Or perhaps the Americans had finally learned it.

General Derpanser troopa Herman Balk considered one of Germany’s finest tactical commanders was more analytical. Patton understood something fundamental that in modern warfare the side that can respond faster controls the operational tempo. He didn’t wait for perfect conditions or complete information. He acted decisively with what he had.

This is what we did in our victories. By 1944, we had become cautious and slow. Patton remained aggressive and fast. That difference determined the outcome. Even Model, who had directly opposed Patton’s third army, acknowledged the achievement. Before his suicide in April 1945, Mod told his staff, “If Germany had commanders who could operate with Patton’s speed and flexibility, we would have won this war.

Our early victories made us arrogant. We believed our doctrine was superior. Patton proved that doctrine matters less than execution and his execution was flawless. Perhaps most telling was the assessment of General Oburst Hines Gderion who had initially said he would rewrite his understanding of armored operations if Patton succeeded.

In postwar interviews, Gudderion admitted, “I did not believe it possible. The logistics alone should have taken a week to coordinate. The movement through winter conditions should have been chaotic. The attack should have been disorganized and peacemeal. Instead, Patton achieved nearperfect coordination. His staff work was superb.

His commanders executed brilliantly. His logistics officers performed miracles. This was not luck. This was operational excellence at every level of command. German military historians writing in the decades after the war were equally respectful. General dear Infantry Hans Spidel who served as Raml’s chief of staff wrote in his memoir, “The relief of Bastonia stands as one of the finest examples of operational art in military history.

Students at every war college should study not just what Patton did, but how his entire army executed so flawlessly under impossible conditions. The ultimate German judgment on Patton came from an unlikely source. ordinary German soldiers in P camps after the war. Captured Germans frequently mentioned Third Army’s relief of Bastonia as the moment they knew Germany would lose.

One former Panzer commander said, “When Patton turned his army in a blizzard and attacked within 2 days, we knew we were beaten. Not just beaten in that battle, but beaten in the war. We no longer had the quality of leadership or the capability of execution to compete with such an enemy.” German high command had learned too late what Patton’s own soldiers already knew.

Old blood and guts was more than a theatrical general with ivory-handled revolvers. He was an operational genius who could accomplish what others considered impossible. If this deep dive into German high command stunned reaction to Patton’s impossible achievement fascinated you, then you need to subscribe to this channel immediately.

We’re bringing you the untold stories from both sides of history’s greatest conflicts. The reality behind the legends, the voices you’ve never heard, the perspectives that change everything you thought you knew about World War II. Hit that notification bell so you never miss our next video. We’ve got incredible content coming about other moments that shocked military commanders, battles that changed history, and the truth behind famous operations.

Drop a comment telling us what aspect of the Battle of the Bulge you want us to explore next. the German perspective on Bastonia’s defense, the American soldiers who held the line, the intelligence failures that led to the surprise.