January 1945. The island of Luzon is burning under the weight of a collapsing Japanese empire. Explosions echo across the hills. Tracer rounds carve through the darkness. And somewhere, between shattered villages and flooded rice patties, tens of thousands of Japanese civilians flee. Terrified not only of the fighting, but of the horror stories they were told about the approaching Americans.

For days, groups of exhausted Japanese women wander the outskirts of the battlefield. Some barefoot, some clutching infants, some so weak they can barely stand. Many have spent nights hiding in ditches, ravines, or abandoned huts, surviving on muddy water and handfuls of raw rice. They expect the worst.

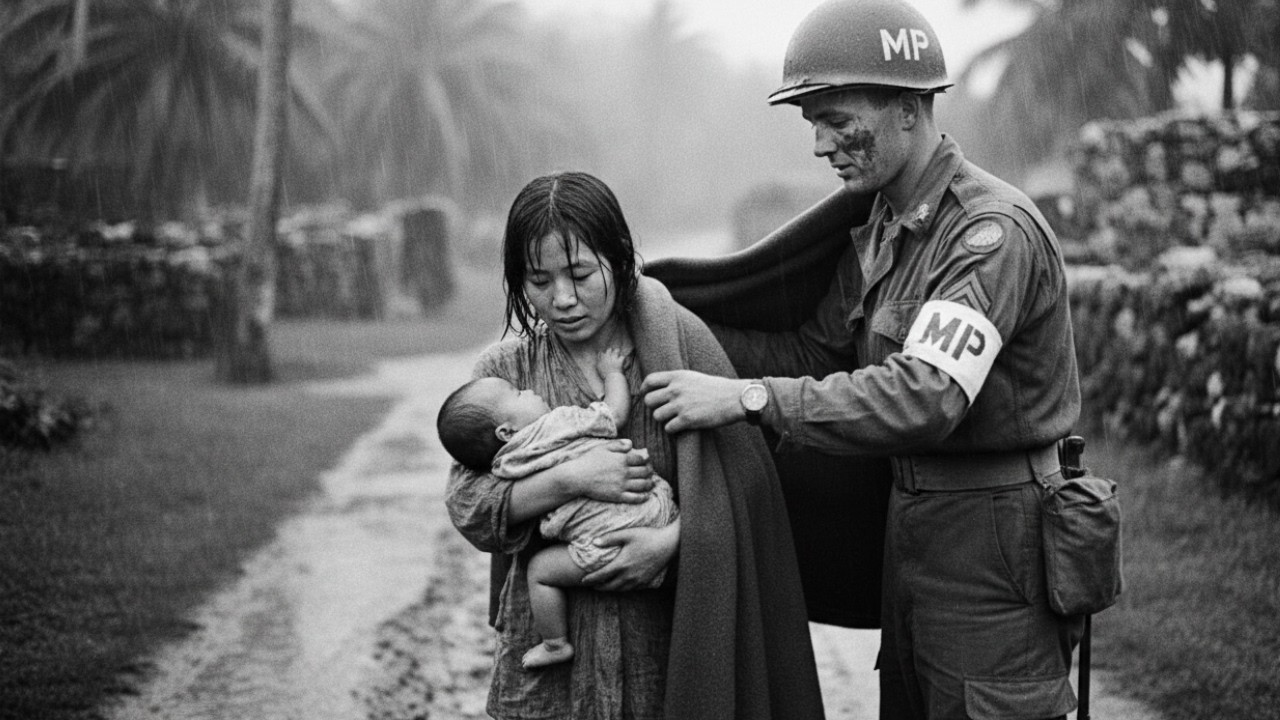

They’ve been told the Americans will kill them, torture them, or worse. But when they finally emerge, shaking, holloweyed, waving white cloth scraps. The American soldiers who meet them are not frontline infantry. They are military police. And what the MPs do next is something almost never shown in war movies, yet documented across multiple Pacific campaigns.

They extend blankets, food, shelter, and protection to the very people the enemy told to fear them most. This is the true story of how American MPs trained for law enforcement, traffic control, and prisoner processing became unexpected humanitarians in one of the war’s most desperate theaters. The first reports come from small villages on Luzon’s west coast, places with names like San Fabian, Demortis, Rosario.

American units push inland, followed closely by military police detachments whose job is to secure rear areas, direct troop movement, and prevent sabotage. But what they find are not saboturs. They find women, grandmothers, pregnant mothers, teenage girls, stumbling out of the jungle in groups of three or four, half starved, shivering despite the tropical heat.

Some have not eaten in three days. Many collapse the moment they reach the American perimeter. And contrary to the propaganda drilled into them, they are not shot. They are not arrested. The first MP on scene often kneels down, rifle slung behind him, and simply says in slow English with gestures, “It’s okay. You’re safe now.

” Others offer water cantens, guiding the women away from the chaos of the front. Word spreads quickly across the division. Civilians are coming in, lots of them, and the MPs become the point men for a humanitarian mission they never trained for. Behind the lines, MPs improvise shelters using whatever they can find. Torn tarps, truck canvases, spare ponchos.

They clear out old supply shacks, abandoned Filipino homes, even half-destroyed rice warehouses, transforming them into temporary safe zones. Blankets, army issue wool, rough but warm, are passed out one by one. The MPs give up their own blankets, too, because the civilians are shaking from exhaustion, dehydration, and sheer terror.

Many women clutch the blankets like lifelines, holding them to their faces as if the soft fabric alone proves the nightmare is ending. American medics eventually arrive, but in the first critical hours, it is the MPs who are boiling water on field stoves, tearing open rations, handing out crackers, spam, whatever they can spare. They organize the women into groups, injured, healthy, elderly, mothers with children.

They assign guards not to control the civilians, but to protect them from roaming pockets of Japanese troops who would rather civilians die than surrender. For the MPs, the transformation is jarring. Yesterday, they were directing Sherman tanks through intersections, regulating traffic, arresting drunken soldiers, and processing PS.

Today, they’re passing out blankets to frightened civilians who can’t stop bowing and apologizing, unsure whether kindness is real or a cruel trick. But these moments aren’t isolated. Scenes like this play out on Lee, Saipan, Guam, Okinawa, and dozens of smaller islands. They appear in after action reports, MP diaries, and oral histories recorded decades later.

One MP on Saipan wrote, “Some of the Japanese women wouldn’t look at us when they came in. They were crying.” One woman fainted when I tried to give her water. Later, when she woke up under a blanket, she held my hand and wouldn’t let go. On late day, an MP corporal described finding a group of women hiding in a drainage culvert for two days.

They were too weak to climb out, so the MPs pulled them free one at a time and carried them over their shoulders to safety. On Guam, MPs used their own helmets to scoop water from a stream for dehydrated women who couldn’t walk another step. These were not one-off moments of charity. They were patterns repeated again and again as the Pacific War brought American forces deeper into territories where Japanese civilians had been fed years of terror and misinformation.

It wasn’t always easy. Some women refused blankets out of fear. Some burst into tears the moment an MP approached. Others bowed so deeply and so repeatedly that the MPs grew uncomfortable, unsure how to convince them that they weren’t prisoners. They were guests under American protection. And yet the compassion persisted because these men, though soldiers in a brutal war, understood something essential.

Civilians were not the enemy. And when the women realized the Americans weren’t monsters, their fear slowly dissolved into relief. An MP on Luzon recalled, “One woman kept touching the blanket like she didn’t believe it was real. She hadn’t been warm in days. She looked up at us and said something in Japanese.

We didn’t know the words, but we knew what she meant. The blanket became the first symbol of safety many Japanese civilians had seen since the war reached their villages. Shelter, makeshift, patched together, but safe, became the second. Inside these shelters, women finally slept, some for the first time in nearly a week.

By the second day, the MPs often coordinated with civil affairs units and Filipino guides. These groups helped translate, comfort, and explain the Americans intentions. Together, they formed impromptu relief networks, helping locate lost children, distribute supplies, and move civilians away from military zones. But there was another challenge, one few history books discuss.

Some Japanese soldiers hid among civilians, hoping to slip through MP lines. The MPs had to remain cautious, searching bags, checking for concealed weapons, and separating military-aged men from women and children. And yet, even while performing dangerous security checks, the MPs still handed out blankets and food, they still treated the women with dignity.

This balance, firmness without cruelty, control without intimidation, became the hallmark of MP units throughout the liberation of the Philippines and beyond. One MP sergeant put it best. We didn’t come here to hurt civilians. We came here to end the war. And if ending the war meant giving a scared woman a blanket and a roof, then that was our job, too.

Over time, as more civilians surrendered willingly, trust grew. Some women even assisted American units by pointing out minefields, abandoned hideouts, or locations where wounded civilians still waited in fear. These women had no obligation to help, but the kindness they received built a fragile bridge in the middle of chaos. For the MPs, each new civilian brought a reminder that behind the uniforms and propaganda, behind the flags and languages, there were human beings caught in the storm, women who had lost husbands, mothers searching for missing

sons, elderly grandmothers struggling to walk but refusing to leave younger relatives behind. And in every encounter, the MPs reached for the same simple gestures. A blanket draped over shoulders, a shelter secured against the rain, a cup of warm water, a calm voice saying, “You’re safe now.” But nowhere would this dynamic become more visible, more emotional, or more historically important than on Okinawa, the bloodiest battle of the Pacific.

For weeks, caves and hillside bunkers concealed entire families, women, children, the elderly, driven underground by relentless bombardments, and by years of Japanese military indoctrination, warning them that Americans would slaughter civilians on site. Many women clutched grenades the Japanese army handed out for suicide.

Others held sharpened bamboo spears, convinced they would have to fight to protect their daughters. Okinawa was a nightmare of smoke, broken limestone, and shattered villages. Yet through this devastation, American MPs operated behind the infantry lines, screening civilians, guiding them to safety, and offering the same blankets and temporary shelters that had already saved lives on Luzon, Le, and Saipon.

Journal entries from MP companies on the island tell a consistent story. Groups of Japanese women covered in soot and cave dust emerged with trembling hands raised high expecting death. MPs approached slowly, hands open, rifles slung on their backs. The first thing they offered wasn’t commands. It was water, then blankets, then a calm place to sit.

One MP from the 96th Infantry Division recorded this moment. A woman came out holding a baby no bigger than a loaf of bread. Both were shaking. The baby had no clothes. I took my blanket off my shoulders and wrapped them both. She cried so hard. I thought she was hurt. But she was just relieved. Relief. So sharp, so sudden that many collapsed entirely when they realized the Americans weren’t there to kill them.

Another MP recalled helping a group of five women who had been hiding in a limestone grotto so long that their eyes could barely tolerate daylight. They recoiled when they first saw him, certain he meant to shoot. Instead, he laid a blanket on the ground, spread another over their shoulders, and poured warm water into metal cups.

Hours later, one of the women pressed her forehead to the ground in gratitude. Something that left the MP so overwhelmed, he wrote, “I didn’t want her to bow. I just wanted her to know she didn’t have to be afraid anymore.” Throughout Okinawa, temporary civilian camps sprang up in cane fields, under tarps stretched between ruined homes, or inside abandoned schoolhouses.

MPs managed these camps with a mix of military discipline and human compassion. Blankets became currency, not in a transactional sense, but as symbols of protection. MPs often gave up their own gear so that elderly women could have something dry to sleep on. Rain poured for days at a time, turning the ground into thick mud.

Yet MPs kept working, distributing supplies, organizing shelters, and coordinating with medics. They built makeshift kitchens out of 55gallon drums. They handed out food from captured Japanese stores when army rations weren’t enough. They reassured women who were terrified that surrendering meant dishonor, prison, or worse.

Time and again they explained with hand gestures, smiles, and a few learned Japanese words that surrender did not mean shame. It meant survival. Some MPs even began learning simple phrases. Dai jobu. It’s okay. Mizu water. No more fighting. It wasn’t perfect communication, but it was enough. As civilian groups grew larger, the MP’s protective role expanded.

They prevented panicked crowds from wandering into active battle zones. They intercepted Japanese soldiers who tried to hide among the civilians. They safeguarded women from being mistaken as threats by nervous American infantrymen. In one case documented in Army civil affairs reports, a group of women, exhausted, starving, and emotionally shattered, approached an American checkpoint, waving a makeshift white flag.

A young soldier fired a warning shot into the air, not out of malice, but fear. The women screamed and fell to their knees. An MP sergeant sprinted between them and the soldier, shouting, “Hold your fire. They’re civilians.” He then personally escorted the women to shelter, handing them blankets and sitting with them until they stopped shaking.

Courage in war takes many forms. Sometimes it’s charging a hill. Other times, it’s kneeling beside a terrified woman in the rain and telling her with gestures and tone alone that she is finally safe. across these islands. Interactions like this quietly shifted the trajectory of the occupation and the peace to come.

For many Japanese civilians, their first direct experience with Americans wasn’t violence. It was kindness. A blanket, a warm drink, a sheltered place to rest. One young Okinawan woman later recalled, “We were told the Americans would torture us, but when they gave my grandmother a blanket, she cried and said, “They must be human after all.

” Another survivor remembered that the American MPs never raised their voices. Even when crowds of civilians arrived so exhausted they collapsed before reaching the checkpoint. The MPs simply lifted them, carried them to dry ground, and wrapped them in wool blankets. These gestures didn’t end the pain of war.

They didn’t undo the destruction or bring back the dead. But they mattered deeply, personally, and historically. They planted the seeds for post-war reconciliation. They saved lives that would have been lost to starvation, exposure, or fear-driven suicide. They challenged the propaganda that painted the Americans as monsters.

And they demonstrated that even in the midst of humanity’s darkest moments, compassion can break through. By the war’s end, tens of thousands of Japanese women had received aid from American MPs across the Pacific. The diaries and reports of those MPs reveal something profound. that war is not made only of battles and brutality, but of small mercies that ripple further than anyone expected.

One MP wrote on VJ day, “I came here expecting to fight soldiers. I didn’t expect to carry crying women out of caves and give them blankets, but I’m proud of that part more than anything else I did.” Another wrote simply, “They were tired. They were scared. And we helped them. That’s all that matters.” Today, these moments rarely appear in textbooks or films, overshadowed by the violence of the Pacific campaign.

Yet, they remain critical pieces of the historical record, reminders that even amidst destruction, human beings can choose kindness. American MPs were not saints. They were not perfect. They were ordinary soldiers who stepped into extraordinary circumstances and chose humanity over hatred.

And for countless Japanese women who survived those desperate days, a single blanket handed over by a stranger in uniform meant the difference between despair and hope. It meant warmth. It meant safety. It meant a future. And in the middle of a world at war, that was a miracle in itself.